| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

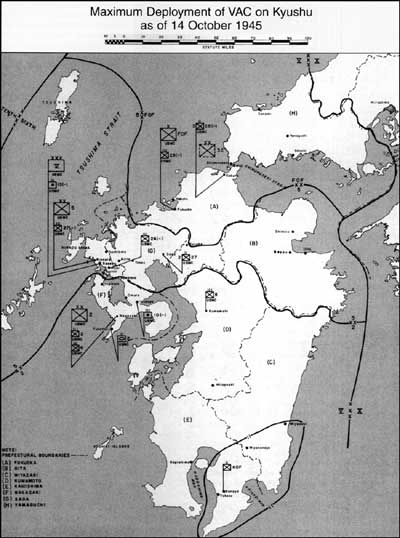

SECURING THE SURRENDER: Marines in the Occupation of Japan by Charles R. Smith Kyushu Occupation The V Amphibious Corps zone of occupation comprised the entire island of Kyushu and Yamaguchi Prefecture on the western tip of Honshu. After the 2d and 5th Marine Divisions had landed, General Schmidt's general plan was for Major General Hunt's 2d Marine Division to expand south of the city of Nagasaki and assume control of Nagasaki, Kumamoto, Miyazaki, and Kagoshima Prefectures. In the meantime, Major General Bourke's 5th Marine Division was to expand east to the prefectures of Saga, Fukuoka, Oita, and Yamaguchi. Bourke's troops were to be relieved in the Fukuoka, Otia, and Yamaguchi areas with the arrival of sufficient elements of Major General William H. Gill's veteran 32d Infantry Division. Preliminary plans for the occupation of Japan had contemplated the establishment of a formal allied military government, similar to that in operation in Germany, coupled with the direct supervision of the disarmament and demobilization of the Japanese Armed Forces. However, during the course of discussions with enemy emissaries in Manila, radical modifications of these plans were made "based on the full cooperation of the Japanese and [including] measures designed to avoid incidents which might result in renewed conflict." Instead of instituting direct military rule, occupation force commanders were to supervise the execution of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers' directives to the Japanese government, keeping in mind Mac Arthur's policy of using, but not supporting, the government. Enemy military forces were to be disarmed and demobilized under their own supervision, and the progressive occupation of assigned areas by Allied troops was to be accomplished as Japanese demobilization was completed. The Japanese government and its armed forces were to shoulder the chief administrative and operational burden of disarmament and demobilization. The infantry regiment, and division artillery operating as infantry, was to be "the chief instrument of demilitarization and control. The entire plan for the imposition of the terms of surrender was based upon the presence of infantry regiments in all the prefectures with in the Japanese homeland." Within the Sixth Army zone, occupational duties were fairly standardized. The division of responsibilities was based upon the boundaries of the prefectures so that the existing Japanese governmental structure could be used. The Sixth Army assigned a number of prefectures to each corps proportionate to the number of troops available. The corps, in turn, assigned a specific number of prefectures to a division. Regiments, usually, were given responsibility for a single prefecture. In the 5th Marine Division zone of responsibility, however, the size of certain prefectures, the large civilian population, and the tactical necessities of troop deployment combined to force modifications of the general scheme of regimental responsibility for a single prefecture. The regiment's method of carrying out its occupational mission varied little between zones and units whether Army or Marine. As a corps extended its zone of responsibility, advance parties, composed of specialized staff officers from higher headquarters and the unit involved, were sent into areas to be occupied. Liaison was established with local Japanese civil and military authorities who provided the parties with information on transportation and harbor facilities, inventories of arms and supplies, and the location of dumps and installations. With this information in hand, the regiment then moved into a bivouac area in or near its zone of responsibility. Reconnaissance patrols consisting of an officer and a rifle squad were sent out to verify the location of reported military installations and check inventories of war materiel and also to search for any unreported facilities and materiel caches. The regimental commander then divided his zone into battalion areas, and battalion commanders could, in turn, assign their companies specific sectors of responsibility. Sanitation details preceded the troops into the areas to oversee the preparation of barracks and messing facilities, since many of the installations to be occupied were in a deplorable condition and insect-ridden. The infantry company or artillery battery thus became the working unit which actually accomplished the destruction or transfer of war materiel and the demobilization of Japanese Armed Forces. Company commanders were empowered to seize military installations within the company zone and, using Japanese military personnel not yet demobilized and laborers obtained through the local Japanese Home Ministry representative, either destroy or turn over to the Home Ministry all materiel within the installation. All war materiel was divided into five categories and was to be disposed of according to SCAP Ordnance and Technical Division directives. The categories were: that to be destroyed or scrapped, such as explosives and armaments not needed for souvenirs or training purposes; that to be used for allied operations, such as telephones, radios, and vehicles; that to be returned to the Japanese Home Ministry, which encompassed food, fuel, clothing, lumber, and medical supplies; that to be issued as trophies; and that to be shipped to the United States as trophies or training gear.

The hazardous job of disposing of explosive ordnance was to be handled by the Japanese with a minimum of American supervision. Explosives were either burned in approved areas, sealed in place if stored in tunnels, or dumped at sea — the latter being the preferred method. Because of the large quantity of ammunition to be disposed of on Kyushu, both divisions would experience difficulties. Japanese shipping was not available in sufficient strength for dumping the ammunition at sea and the large ammunition could not be blown up as there were no suitable areas in which to detonate it safely. Metal items declared surplus were to be rendered ineffective, by Japanese labor, and turned over to the Japanese as scrap for peacetime civilian uses. Food items and other nonmilitary stocks were to be returned to the Japanese for the relief of the local civilian population. While local police were given the responsibility of maintaining law and order and enforcing SCAP democratization decrees, Allied forces were to maintain a constant surveillance over Japanese methods of government. Intelligence and military government personnel, working with the occupying troops, were tasked with stamping out any hint of a return to militarism, looking for evidence of evasion or avoidance of the surrender terms, and detecting and suppressing movements considered detrimental to the interests of allied forces. Known or suspected war criminals were to be apprehended and sent to Tokyo for processing and possible arraignment before an allied tribunal. In addition, occupation forces were responsible for insuring the smooth processing of hundreds of thousands of military personnel and civilians returning from Japan's now defunct Empire. Repatriation centers would be established at Kagoshima, Hario near Sasebo, and Hakata near Fukuoka. Each incoming soldier or sailor would be sprayed with DDT, examined and inoculated for typhus and smallpox, provided with food, and transported to his final destination in Japan. Both line and medical personnel were assigned to supervise the Japanese-run centers. At the same time thousands of Korean and Chinese prisoners and conscript laborers had to be collected and returned to their homelands. In the repatriation operations, Japanese vessels and crews would be used to the fullest extent possible to conserve Allied manpower and allow for an accelerated program of postwar demobilization.

This pattern of progressive occupation was quickly established in V Amphibious Corps zone of responsibility. During the last days of September, both of the Corps' divisions concentrated on unloading at Sasebo and Nagasaki, moving supplies into dumps, organizing billeting areas, securing local military installations, and preparing elements for the expansion eastward. In addition to normal occupation duties, both divisions became saddled with the job of unloading "a terrific amount of shipping." As Lieutenant Colonel Jacob Goldberg wrote at the time: "we are building up a mountain of supplies consisting of items we will never be able to use and I can fore see the day when we just leave it all for the Japs . . . . Everyone in the Pacific is apparently getting rid of their excess materiel by shipping it to Japan, regardless of whether anyone in Japan needs it. One word describes the situation: SNAFU." Confirming Goldberg's assessment, Major Norman Hatch later noted that the Marines, after days on C- and K-rations were getting "fed up with this, and occasionally a big refrigerator ship would come in and everybody would say, . . . 'Now we'll get some fresh food,' but we'd find that the cold lockers were loaded with barbed wire, ping pong balls, things of that nature . . . .What we would do with barbed wire in Japan nobody had the slightest idea."

On 25 September, two days after landing at Sasebo, General Bourke's division began expanding its assigned zone of occupation and patrols were sent into outlaying areas. The Marines found Japanese civilian and military personnel to be cooperative, but as they initially found in the city, most women and children in rural areas appeared frightened. As the Japanese grew accustomed to the Marine presence and more assured that they would not be harmed, their initial shyness and fear soon disappeared. During the next few days, all main routes within the division's zone were covered even though most were in poor repair, "some not negotiable by anything but jeeps." As the expansion continued, Japanese guards were relieved at military installations and storage areas; the inventorying of Japanese equipment was begun; liaison was established with local military and civilian leaders; and Marine guards were stationed at post offices and city halls. Within a week of landing, the division's zone of responsibility again was expanded to include Yagahara, Miyazaki, Arita, Takeo, Saishi, Sechihara, Imabuku, and a number of other towns to the north and west of Sasebo. On 29 September, the division's zone was enlarged further to include Fukuoka, the largest city on Kyushu and administrative center of the northwestern coal and steel region. Since Fukuoka harbor was littered with pressure mines dropped by American Air Forces, movement to the city was made by rail and road instead of by ship from Sasebo. An advance billeting and reconnaissance party, headed by Colonel Walter Wensinger, reached Fukuoka on 27 September and held preliminary meetings with local civil and military officials. Brigadier General Ray A. Robinson, the division's assistant commander, was given command of the Fukuoka region occupation force which consisted of the 28th Marines reinforced with artillery and engineers and augmented by Army detachments. Lead elements of Robinson's force began arriving on the 30th, and by 5 October the force had completed the move from Sasebo. "All the way up [to Fukuoka]," as General Robinson recalled later, "when we stopped at a station, the equivalent of our Red Cross girls, these Japanese women, would come down with tea and cakes. They'd been our enemies . . . so we thought they were going to poison us, so nobody took 'em!"

The Fukuoka Occupation Force, which was placed directly under General Schmidt's command, immediately began sending reconnaissance parties followed by company and battalion-sized forces into the major cities of northern Kyushu. But because of the limited number of troops available and the large area to be covered, Japanese guards were left in charge of most military installations, and effective control of the zone was maintained by motorized patrols. To prevent possible outbreaks of mob violence, Marine guard detachments were set up to administer Chinese labor camps found in the area, and Japanese Army supplies were requisitioned to feed and clothe the former prisoners of war and laborers. Some of the supplies also were given to the thousands of Koreans who had gathered in temporary camps near the principal repatriation ports of Fukuoka and Senzaki in Yamaguchi Prefecture, where they waited for ships to carry them back to their homeland. The Marines, in addition to supervising the loading out of the Koreans, checked on the processing and discharge procedures used to handle Japanese troops returning with each incoming vessel. In addition, the branches of the Bank of Chosen were seized and closed in an effort to crush suspected illegal foreign exchange operations. Like their counterparts in other areas of Kyushu. Robinson's occupation force located and inventoried vast quantities of Japanese war materiel for later disposition by the 32d Infantry Division. On 4 October, Robinson dispatched Company K, 3d Battalion, 28th Marines, across the Shimonoseki Straits into Yamaguchi Prefecture, further expanding the force's zone of control. Another reinforced company was sent two days later to occupy Moji and Yawata, on the Kyushu side of the straits. On the 11th, a detachment was sent from Shimonoseki to Yamaguchi; advance parties reached the city of Oita on the 12th; and on the 19th occupation forces were set up at Senzaki. As General Robinson's force took control of Fukuoka and Yamaguchi Prefectures and penetrated Oita Prefecture, the 5th Marine Division expanded its hold on areas east and west of Sasebo. On 2 October, the division's reconnaissance company was dispatched to Hirado Island. Moving overland to Hainoura by DUKWs, the amphibian trucks were used to "swim" the narrow channel to Hirado. As elsewhere, they found the Japanese on the island in full "compliance with surrender terms." Other elements of the 5th Division followed, destroying defenses, collecting materiel, and reconnoitering the small islands of Gotto Retto, Kuro Shima, Taka Shima, Tokoi Shima, and A Shima, west of Sasebo. On 5 October, the division's zone of responsibility was extended to include Saga Prefecture and the city of Kurume in the center of the island. On the 9th, the 2d Battalion, 27th Marines, operating as an independent occupation group, moved to Saga city. Two weeks later, the regiment, less the 1st Battalion, established its headquarters in Kurume and assumed responsibility for the central portion of the division zone, which now extended to the east to Oita Prefecture. For each of the division's movements, advance billeting and reconnaissance parties were sent to the areas to contact local authorities and arrange for the occupation. Since one of the greatest problems was sanitation, sanitation squads accompanied each party in order to prepare billeting areas. Wherever possible, Japanese labor was used to improve living conditions for the troops. In addition, the maintenance of roads and bridges was a constant problem since the island's inadequate road network quickly disintegrated under military traffic. The situation was further aggravated by heavy rainfall and the lack of suitable repair materials. Although roads were passable only for jeeps, no attempt was made to use motor transport between major cities except for special patrols. Therefore, the major burden of supplying and transporting the scattered elements of the Marine amphibious corps fell to the Japanese rail system.

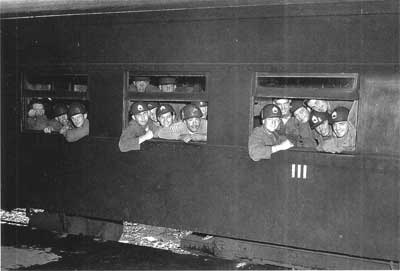

When it was decided to occupy Oita Prefecture, the entire 180-mile trip from Sasebo to Oita city was made by rail. The occupation group, Company A, 5th Tank Battalion, operating as infantry since tanks could not be used on the island's roads, set up in the city on 13 October and conducted a reconnaissance of the surrounding military installations using motorized patrols. The group's size severely limited its activities and therefore most inventory work had to be carried out by the Japanese under Marine supervision. From Oita, elements of the company moved northwest along the coast to Beppu, noted for its hot springs, beaches, and shore resorts. The tankers of Company A remained in the coastal prefecture until relieved by 32d Division troops in early November. By mid-October, elements of the 5th Marine Division were dispersed so as to permit almost complete control of the key areas in the northern portion of the V Amphibious Corps zone. The 2d and 3d Battalions, 27th Marines controlled the cities of Saga and Kurume, the 26th Marines occupied Sasebo and the surrounding region, and the 28th Marines controlled the eastern prefectures of Fukuoka, Oita, and Yamaguchi. The 13th Marines, occupying the area to the south and east of Sasebo in Nagasaki and Saga Prefectures, supervised the processing of Japanese repatriates returning from China and Korea, and handled the disposition of the weapons, equipment, and ammunition stored in naval depots near Sasebo and Kawatana. The 1st Battalion, 27th Marines, detached from its regiment, was stationed in Sasebo under division control and furnished a portion of the city's garrison as well as detachments which searched the islands off shore. In addition to routine occupation duties, elements of the division conducted a number of coordinated surprise searches of schools, temples, and shrines. Only a small number of unreported swords, rifles, technical instruments, documents were seized in the raids.

On 13 October, the 26th Marines was alerted for transfer to the Palau Islands. While the regiment made preparations to move to Peleliu to supervise the repatriation of Japanese troops from the Western Carolines, the first elements of the 32d Infantry Division began landing at Sasebo. The 128th Infantry, followed by the 126th Infantry and division troops, moved through the port and boarded trains for Fukuoka, Kokura, and Shimonoseki, where Robinson's occupation force assumed temporary command of the two Army units. The 127th Infantry, less the 1st Battalion at Kanoya airfield, landed on 18 October, passed to the control of the 5th Marine Division, and on the 19th relieved the 26th Marines of its occupation duties in Sasebo. On 24 October, Major General Schmidt dissolved the Fukuoka Occupation Force and 32d Infantry Division, now commanded by Brigadier General Robert B. McBride, Jr., opened its command post in Fukuoka. A base command, composed of the service elements that had been assigned to General Robinson's force, was set up to support operations in Northern Kyushu and continued to function until 25 November when it was disbanded and the 32d Division assumed its duties. The division's three regimental combat teams, comprising infantry, artillery, and attached service troops, relieved the 28th Marines and 5th Tank Battalion: the 128th Infantry with the 1st Battalion at Shimonoseki, the 2d Battalion at Bofu, and the remainder of the regiment at Yamaguchi, controlled Yamaguchi Prefecture; the 126th at Kokura patrolled east and south through Fukuoka and Oita Prefectures; and the 127th, after being relieved by the 28th Marines in the zone formerly occupied by the 26th Marines, occupied Fukuoka and the zone to the north. The 26th Marines began boarding ship on 18 October and the following day was detached from the division and returned to FMFPac control. Before the transports departed on 21st, orders were received from FMFPac designating the 2d Battalion for disbandment and the battalion returned to Ainoura, the 5th Division Headquarters' camp just outside of Sasebo. On 30 October, the 2d Battalion ended its Pacific service and passed out of existence, its men being transferred to other units. As the Army's 32d Infantry Division entered Fukuoka and Oita Prefectures, Major General Hunt's 2d Marine Division gradually expanded its hold on southern Kyushu following an intensive reconnaissance effort. The 2d and 6th Marines had moved into billets in the vicinity of Nagasaki immediately after landing with the mission of surveillance and disposition of enemy military materiel in the immediate countryside and the many small nearby islands. The 8th and 10th Marines had gone directly from their transports to barracks at Isahaya and began patrols of the peninsula to the south and throughout the remainder of Nagasaki Prefecture in the 2d Division zone. Also construction began on an airstrip in the atomic-bombed-out area of Nagasaki, capable of handling the planes of Marine Observation Squadron 2. Within days, the squadron began air courier service from "Atomic Field." On 4 October, V Amphibious Corps changed the occupational boundary between the two Marine divisions, shifting control of Omura to General Hunt's command. The 3d Battalion, 10th Marines, relieved the reinforced company from 1st Battalion, 27th Marines, as the security detachment for the Marine air base and the unit was returned to the 5th Marine Division. Shortly there after, the 10th Marines assumed control of the whole of the 8th Marines' area in Nagasaki Prefecture.

The corps expanded the 2d Division zone of occupation on 5 October to include the highly industrialized prefecture of Kumamoto in central Kyushu. An advance billeting, sanitation, and reconnaissance party travelled to Kumamoto city to contact Japanese authorities and pave the way for the 8th Marines' assumption of control. By 18 October, all units of the regiment were established in and around Kumamoto and began the process of inventorying and disposing of Japanese war material. Carrying out SCAP directives outlining measures to restore the civilian economy, the Marines, and accompanying military government teams, contacted local officials and assisted wherever possible in speeding the conversion of war industries to essential peacetime production. The 2d Division gradually took control of the unoccupied portion of southern Kyushu during the next month. Advance parties headed by senior field commanders contacted civil and military officials in Kagoshima and Miyazaki Prefectures to insure compliance with surrender terms and adequate preparations for the reception of division troops. Miyazaki Prefecture and the remaining portion of Kagoshima east of Kagoshima Wan were assigned to the 2d Marines. The remaining half of Kagoshima Prefecture was added to the 8th Marines' zone; later, the regiment was also given responsibility for the Osumi and Koshiki Island groups, which lay to the south and southwest of Kyushu. On 29 October, the 1st Battalion, 8th Marines, the first major element of the division to move to southernmost Kyushu. departed Kumamoto for Kagoshima city by truck convoy. The 3d Battalion followed several days later, occupying the inland city of Hitoyoshi. Once in place, the battalions began the now all-too-familiar routine of reconnaissance, inspection, inventory, and disposition. The 2d Battalion, 2d Marines, assigned to the eastern half of Kagoshima, found much of the preliminary occupation work completed. The 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, which had maintained a refueling and resupply point at Kanoya, had been actively patrolling the area since its arrival in early September. When 2d Battalion, loaded in four landing ships, arrived from Nagasaki on 27 October, it was relatively easy to effect the relief. The Marines landed at Takasu, port for Kanoya, and moved by rail and road to the air field. Three days later, the Marine battalion assumed operational control of the Army Air Force detachment manning the emergency field, and the Army detachment returned to Sasebo to rejoin its parent command. In early November, the 2d Marines' remaining two battalions also moved by sea from Sasebo to Takasu and thence by rail to Miyazaki Prefecture. The regimental headquarters and the 3d Battalion arrived at Kanoya on the 5th and moved to Miyakonojo, where they established the command post and base of operations. The 1st Battalion sailed from Nagasaki on the 9th, arrived at Kanoya the following day, and then boarded trains for Miyazaki city on the east coast of Kyushu. By mid-November, with the occupation of Miyazaki, General Schmidt's command had established effective control over its assigned zone of responsibility.

By the end of November, V Amphibious Corps reported substantial progress in its major occupation tasks. More than 700,000 Japanese military and civilians returning from Korea and the South Pacific had been processed through the Corps' authorized ports and separation centers at Sasebo, Kagoshima-Kajiki, Fukuoka, Shimonoseki, and Senzaki. Local commanders had shouldered the main burden of setting up the organization and machinery necessary to supervise the orderly, rapid, and sanitary processing for further movement by ship and rail of the incoming Japanese repatriates. In addition, more than 273,000 Koreans, Chinese, Okinawans, and other displaced persons had been sent back to their homelands. While the incoming Japanese presented little problem, the outgoing Chinese, Koreans, and Formosans did. Eager for freedom and naturally resentful of their virtual enslavement under the Japanese, they caused frequent disturbances and riots which had to be quelled by corps troops. In addition, their previous "animal-like living conditions made them a sanitary menace wherever assembled."

Only about 20,000 Japanese Army and Navy personnel remained on duty, all employed in demobilization, repatriation, minesweeping, and similar supervised occupational activities. While initial feelings were mixed, a good rapport soon developed between the Marines and their Japanese counterparts. "We were operating off LSTs [in the Tsushima Islands] during the day and blowing up guns and destroying ammunition, and I particularly remember the Japanese who did the job," Lieutenant Edwin Neville later recalled. "After one spectacular blow-up, they pulled out bottles of potato whiskey. That is all the booze they had, but they shared them with the Americans. They did not have much to look forward to except mustering out, but that was okay, and we were okay." On 1 December, in accordance with SCAP directives, the remaining Japanese military forces were transferred to civilian status under newly created government ministries and bureaus. The need for large numbers of combat troops in Japan steadily lessened as the occupation wore on, and it became increasingly obvious that the Japanese intended to offer no resistance. The first major Marine unit to fulfill its mission in southern Japan and return to the United States was MAG-22. On 14 October, Admiral Spruance, acting for CinCPac, queried the Fifth Fighter Command as to whether the Marine aircraft group was still needed to support the Sasebo area occupation forces. On the 26th, the Army replied that MAG-22 was no longer needed, and it was returned to operational control of the Navy. The group's service squadron and heavy equipment which had just arrived from Okinawa were kept on board ship, and on 2 November, Air FMFPac directed that the unit return to the United States. The group's 72 Corsairs were flown to the naval aircraft replacement pool on Okinawa, the pilots returning to Kyushu by transport plane. On 10 November, a majority of the group's personnel boarded the SS Sea Sturgeon at anchor in Sasebo Harbor. Included were 485 low-point officers and enlisted men being transferred to MAG-31 at Yokosuka as replacements for those eligible for rotation or discharge. The transport weighed anchor on the 12th and sailed for Yokosuka, skirting the southern tip of the island instead of heading through Shimonoseki Straits which was still heavily mined. Upon arrival, the group spent the next several days at anchor in Tokyo Bay taking on fuel and provisions. "The one bright spot was a liberty party to the Tokyo area on 17 November," reported Colonel Elliott E. Bard, the group's new commanding officer. "At 0800 approximately 450 of the Group's personnel went over the side and down the ladder into a waiting LSM for the two-hour trip to Tokyo. Time there was passed sightseeing, buying souvenirs, lunching at the Imperial Hotel, and visiting the non-restricted section of the Imperial grounds surrounding Hirohito's palace. All agreed that the day was well spent." On 20 November, after picking up MAG-31's 598 returnees at Yokosuka and more than 800 Army troops at Yokohama, MAG-22 sailed for the United States. The Marine Air Base at Omura remained in operation, but its aircraft strength consisted mainly of Marine Observation Squadron 2's light liaison and observation planes which flew courier, reconnaissance, medical evacuation, and, more importantly, daily mail flights. Although a third Marine air base was planned at Iwakuni to support operations in the Iwakuni Hiroshima-Kure area, it was not established and the transport squadrons of MAG-21 slated to occupy the base were reassigned to Guam and Yokosuka. The redeployment of MAG-22 began the gradual drawdown of excess occupation forces on Kyushu. On 12 November, Sixth Army was informed by V Amphibious Corps that the 5th Marine Division would be released from its duties and returned to the United States in December. By early 1946, the 2d Marine Division would be the only major Marine unit remaining on occupation duty in southern Japan.

|