|

National Park Service

"Do Things Right the First Time": Administrative History: The National Park Service and the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980 |

|

|

Chapter One: A. The National Park System in Alaska, 1910-1970 On January 11, 1972, the National Park Service forwarded its preliminary recommendations for withdrawal of twenty-one areas totaling 44,169,600 acres of land in Alaska for study as possible additions to the National Park System. [1] Part of a general Department of the Interior preliminary proposal that totaled 101,373,600 acres, the recommendations were mandated by section 17(d)(2) of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) of December 18, 1971. [2]

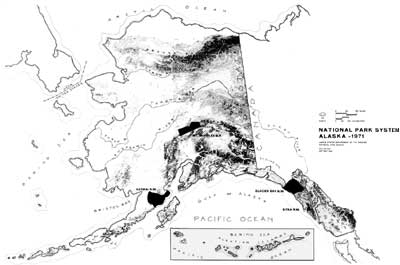

These preliminary recommendations were put together in a matter of days after the passage of ANCSA. They were not whimsical, however, but were based on a body of knowledge of the resources of Alaska gained through years of experience and study there. By 1972 the National Park Service administered four areas in Alaska that totaled just over 7,545,000 acres. [3] The Service had established a presence there, that, while too often superficial, perhaps, existed from its earliest days as an organization. In light of later events, it is perhaps ironic that the origin of the National Park System in Alaska is to be found in President William Howard Taft's use of the Antiquities Act of 1906. Responding to a report that documented the destruction of resources in a public park (Totem Park) in the small southeastern Alaska fishing village of Sitka, President Taft invoked the Antiquities Act to establish Sitka National Monument on March 23, 1910. [4] Sitka National Monument was established to protect significant historic and cultural resources relating to the Russian-Tlingit battle of 1804, and cultural artifacts of southeast Alaska Natives. [5] Use of the proclamation provision for Sitka was not, however, the last time a president would invoke the Antiquities Act to protect what he deemed to be nationally significant resources in Alaska. In fact, before 1970 the National Park System in Alaska was one that existed primarily by executive action. The one exception was the 1,408,000-acre Mt. McKinley National Park, authorized on February 26, 1917, to protect the wildlife in an area of incomparable grandeur that included portions of the highest mountain in North America. [6] Establishment of Mount McKinley National Park was not the result of any broadbased movement, but, rather, was due largely to the efforts of the Boone and Crockett Club and, in particular, its game committee chairman, Charles T. Sheldon. Valuable support came from the Camp Fire Club of America, American Game Protective Association, and key officials in the Department of the Interior, including Assistant Secretary Stephen T. Mather, who would soon become the first director of the newly-created National Park Service. [7] It was Sheldon, however, a well-known naturalist, who first conceived of "Denali" National Park when he wintered on the Toklat River in 1907-08, initiated the process, secured the approval of Department of the Interior officials, did much to drum up support for the proposal, and drafted the initial boundaries. [8] Despite support from conservation groups, Department of the Interior officials, the governor of the territory of Alaska, and Alaska's delegate to Congress, James Wickersham, who introduced the bill in April 1916, the proposal ran into unexpected opposition in Congress—much of which apparently had little to do with the proposal itself. The bill was reported out of the House Committee on Public lands late in the session and passed the full House on February 19, 1917. The next day the Senate, which had already passed Senator Key Pittman's version of the bill, concurred in the amended House bill. President Woodrow Wilson signed the bill into law on February 26, 1917. [9] Officials in the newly-created National Park Service were surely pleased with passage of the bill that brought Mount McKinley National Park into the National Park System. Yet at the same time, they were concerned that the problems the bill encountered in the House might imperil future park projects. [10] As a result, when Robert F. Griggs and the National Geographic Society proposed establishing a national park in an area of extreme volcanic activity on the Alaska Peninsula later in 1917, Acting NPS Director Horace M. Albright indicated that such an action was impossible. [11] Although he personally agreed that the area surrounding Mt. Katmai, which still displayed the affects of a violent eruption that occurred in 1912, met national park criteria, Albright believed that protection would have to come through presidential, not congressional action. [12] Accordingly, Griggs and the National Geographic Society, aided by NPS officials, undertook a campaign that culminated when President Woodrow Wilson set aside the 1,087,990-acre Katmai National Monument on September 24, 1918. [13] The monument, which included primarily the active volcanic peaks surrounding Mt. Katmai, the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, and the most promising east and west access routes, was set aside, President Wilson said in his proclamation, to preserve an area that would

The proclamation made no mention of the wildlife, particularly bears, that is so significant a part of the visitor experience at Katmai today. Using the Antiquities Act to establish Katmai National Monument allowed the Service and its friends to protect an area of unquestioned national significance while avoiding a potentially costly battle in Congress. At the same time, it exposed another problem that is familiar today—the opposition of most Alaskans to withdrawal of lands by the executive branch of the Federal Government. This view was expressed in a letter from Territorial Governor Thomas Riggs, Jr., shortly after the establishment of Katmai National Monument:

Six years later, when another group sought to secure preservation of an area at Glacier Bay, the editors of the Juneau Empire expressed the attitude of Alaskans toward land withdrawals. Calling the proposal "A Monstrous Proposition," the paper said:

"It leads one to wonder," the editors wrote, "if Washington has gone crazy through catering to conservation faddists." [15] The fury of the editors of the Juneau Empire had been aroused when President Calvin Coolidge ordered the temporary withdrawal of land at Glacier Bay, pending determination of an area to be permanently withdrawn as a national monument. [16] The next year, following resolution of a conflict over boundaries, President Coolidge invoked the Antiquities Act to establish the 1,164,800-acre Glacier Bay National Monument. [17] As was the case with Katmai National Monument, the movement to establish a national monument at Glacier Bay was due primarily to the efforts of scientists and conservationists—in this case, the National Ecological Society—and the area was set aside to reserve a significant resource for scientific research. [18] In fact, with the exception of a statement regarding accessibility, the reasons for protection in the President's proclamation were those originally drafted by the National Ecological Society: protection of tidewater glaciers and a large stand of coastal forests in natural conditions, the unique opportunity for scientific study "of glacier behavior and of resulting movements and development of flora and fauna and of certain valuable relics of ancient interglacial forests." [19] One additional area—Old Kasaan National Monument—was administered by the Service for some twenty years. Located on Prince of Wales Island in Southeast Alaska, Old Kasaan was set aside by President Woodrow Wilson on October 25, 1916, to protect the ruins of a former Haida Indian Village. [20] Because Old Kasaan was in Tongass National Forest, the monument was originally administered by the Forest Service. Administration was transferred to the NPS by Executive Order 6166 on August 10, 1933. [21] The monument was abolished on August 25, 1955. [22] With establishment of Glacier Bay National Monument, the National Park System in Alaska prior to 1972 was complete, save boundary adjustments and the transitory inclusion of Old Kasaan National Monument. In addition to the one historical area (Sitka National Monument), the system consisted of three natural areas that were places of superlative beauty and grandeur seldom matched elsewhere. Moreover, Katmai and Glacier Bay were recognized as being unique living laboratories for students of volcanism and glaciology, and Mt. McKinley National Park was recognized, as it is today, as one of the world's great wildlife reserves. It was, too, a system that reflected some of the unique conditions encountered in Alaska. In size alone, the parks mirrored the place—only Yellowstone exceeded the three natural Alaskan areas in size in 1925. The four Alaska areas made up slightly more than forty percent of the total acreage of lands administered by the National Park Service in 1925. [23] An examination of the legislation, moreover, reveals at least some effort to make adjustments to unique conditions in Alaska. Mount McKinley National Park, for example, was left open for mining, and section 6 of the enabling legislation of that park stipulated that "prospectors and miners engaged in prospecting or mining in said park may take and kill therein so much game as may be necessary for their actual necessities when short of food." [24] Despite such efforts to make the areas more palatable to Alaskans by tailoring the legislation to local concerns, the Alaska park units existed primarily as a result of executive action taken under the authority of the Antiquities Act of 1906. Particularly in the anti-government, individualistic Alaskan society, this meant that neither the areas nor the agency that managed them would enjoy the broadbased support most often enjoyed in the "Lower 48." [25] Combined with the size of the areas and distance from the central office, this lack of support, that sometimes amounted to hostility, would have made the job of managing the Alaska areas difficult at best. Given a parsimonious Congress, the nature of the organization of the Service itself and its interpretation of its mission, providing adequate management of the Alaskan areas was, until the 1960s, something that too often eluded the National Park Service. B. NPS Administration in Alaska, 1916-1950 Vandalism to nationally significant resources moved President William Howard Taft to proclaim Sitka National Monument. Yet, when he did so, no effective administrative machinery existed within the Department of the Interior for managing and protecting the national monuments. [26] No individual or office within the department was responsible for the existing national parks. Although a certain general responsibility for administering the national monuments under the Interior Department had devolved upon the General Land Office (later Bureau of Land Management) the lack of funds prohibited any effective management. Year after year Congress refused to appropriate anything for managing the monuments, and when it finally did in 1916, the amount was only $3,509 to be divided among nineteen monuments. The result was that before 1916 no effective preservation or restoration work could be undertaken at the monuments, and what supervision existed had not "prevented vandalism, unauthorized exploration, or spoliation." [27] After the newly-created National Park Service took control of the national parks and monuments under the jurisdiction of the Department of the Interior in 1917, a custodian, W. Merrill of Sitka, was appointed to oversee Sitka National Monument. [28] Over the next several years the Service began to make some much needed repairs there. It concluded an agreement with the Alaska Road Commission to do the work, and allotted $1,000 in 1918 and $1,102.48 in 1924 for improvement projects that included repair and painting of the totem poles. [29] In general it is apparent, however, that creation of an organization with specific responsibility for administering the national parks and monuments had a much lesser effect on the Alaskan areas than it did elsewhere. Distance to Alaska was a significant factor. Successive NPS directors did visit Alaska, beginning with NPS Director Mather's 1926 trip. [30] However, Alaska was reached primarily by boat before the 1940s. Even after that, the areas were too far, too remote, and communication was too difficult to have had a significant impact on policymakers in Washington, D.C. Organization of the Service was not something that could overcome this problem. Until 1937 superintendents and custodians reported directly to the Washington Office. After the Service established regional offices in that year, managers of the Alaska areas were responsible to the regional director in San Francisco, something that did little to overcome the essential problem of distance. [31] Following World War II, several people, including Director Newton B. Drury, indicated a growing concern over the problem of communication between the central offices and park managers in Alaska, and recommended establishing a NPS Alaska Office in Juneau. [32] Such suggestions were ignored until the mid-1960s, however. Management priorities established by the Service in the 1920s and 1930s worked to the disadvantage of the Alaska areas as well. NPS Director Mather was determined to guarantee the national parks a firm place in the nation's consciousness. [33] One way to do so was an extensive publicity campaign to make the parks more well known. A second was to make park development a management priority in an effort to make the areas more pleasant places to visit. This meant quite simply that funds would go primarily to areas with high visibility and high visitation. The Alaskan areas had neither. Generally, they had the lowest visitation in the system. Mt. McKinley did not record a purely park visit until 1922, although many people with mining business at Kantishna traveled through the park. [34] From 1921 to 1930, Mt. McKinley reported 4,284 visitors. During that time only 32 people reportedly visited Katmai. By way of comparison, Yellowstone National Park reported a total of 1,724,880 visitors during those years. [35] In the 1930s energies within the Service were expended, in large part, in dealing with the myriad recovery programs in which it was involved, incorporating the more than sixty areas that came into the system through the reorganization of 1933, and in dealing with a variety of new kinds of areas established during that decade. [36] Although a detachment of 200 Civilian Conservation Corps men arrived at McKinley in 1938, emphasis remained on areas with highest visitation in the "Lower 48" and Alaska was again forgotten. [37] The attitude of Congress with respect to funding contributed to the difficulty. For the greater part of the period before the 1950s and 1960s, and this included the 1930s, when the Service was the recipient of considerable emergency largesse, Congress steadfastly refused to provide much more than minimal funding for Alaskan areas. The legislation for Mt. McKinley, in fact, included a stipulation that prohibited expenditures of more than $10,000 for maintenance, "unless expressly authorized by law." [38] When the bill passed, moreover, Congress provided no funds for administering the area. It was not until 1921, nearly five years after the park was established, that NPS Director Mather was able to announce that an $8,000 appropriation had allowed the Service to appoint a superintendent and take administrative control of the area. [39] Funding difficulties were not confined to Alaska, it must be made clear. The Service, until the 1930s and again afterwards, generally had difficulty obtaining adequate funding for managing parks and monuments everywhere. This is not to ignore the sometimes heroic efforts of the people on the ground in Alaska. Nor is it to suggest that nothing was accomplished in the first several decades of National Park Service administration there. Between 1922 and 1929 a total of $126,860 was appropriated for Mt. McKinley National Park. [40] This was spent not only for normal administrative and protective activities, but included such things as construction of a headquarters complex between 1925 and 1929, ranger patrol cabins, a trail from McKinley Park Station to Muldrow Glacier, and beginnings of a road that would, when completed in 1938, extend eighty-nine miles from McKinley Park Station to Wonder Lake. [41] In the mid 1930s the Service played a major role in construction of a hotel at the park. Designed and constructed under the supervision of Service personnel, the hotel was completed at a cost of $350,000. [42] Administration of Katmai and Glacier Bay, and later, Old Kasaan national monuments proved to be another story. Funding for national monuments everywhere was always more precarious than it was for the parks. In 1930, for example, only $46,000 was appropriated for protection of all thirty-two national monuments. [43] An added problem was the fact that although the distinction between parks and monuments was often vague, in terms of administration they were different. National parks were to be developed in order that they might become "resort[s] for the people to enjoy," while monuments were areas of national significance to be protected from encroachment. [44] This distinction remained sharper in Alaska for a longer period than it did elsewhere. Added to the factors already discussed, the result was near total neglect of Katmai, Glacier Bay, and Old Kasaan national monuments before 1950. In 1920, in response to an inquiry regarding Katmai, for example, Arno Cammerer wrote that the Service had no immediate plans to develop the area, and because of the lack of adequate transportation, had no representative on location. [45] Twenty years later, when NPS employees Frank T. Been and Victor Cahalane made an inspection tour of Katmai, the situation remained unchanged. Twenty-two years after Katmai was established, Been wrote, "so far as I can determine I am the first National Park Service officer who has visited" the area. [46] In 1963 Lowell Sumner wrote, that as late as 1948 the Service had still not made even the most rudimentary reconnaissance of the area. [47] Similarly, when Been and Earl Trager visited Glacier Bay in 1939, they were apparently the first Park Service employees to have spent any time in the monument, and were among the first to have even visited the area. Although the purpose of their visit indicates an interest in establishing a presence in the area—they were to study possibilities and methods for making the area and its story available to the visiting public—nothing more was done, and the record indicates that Park Service officials visited the area only infrequently until spring 1950. [48] Neglect had its most pronounced effect at Old Kasaan. There is little evidence to indicate that the U.S. Forest Service had done anything to protect the resources there during the period it managed the area. In 1921, in fact, that Service suggested transferring "old totem poles and Indian relics"—the very reason for existence of the monument—to Sitka National Monument. [49] The Park Service assumed jurisdiction, but not management of the area in 1933. Until 1941 direct supervision rested with the Alaska Road Commission under an agreement with the NPS. This arrangement did nothing to reverse the deterioration of the area. No funds were ever expended on the area, and when an inspection was finally made in 1940, the area was so overgrown that walking was virtually impossible, graves were opened, artifacts stolen, and more than half of the totem poles were gone. [50] In 1946, and again in 1954, the Service recommended the abolishment of the monument. The last time it did so in the recognition that the deterioration was irreversible. In 1955 Congress granted the request and abolished the monument. [51] On June 8, 1940, Mt. McKinley National Park Superintendent Frank Been wrote bitterly:

Despite Been's concerns, neglect of the other Alaskan areas did not have so serious consequences as at old Kasaan. Congress' failure to appropriate funds for Mt. McKinley did allow hunting to go on far in excess of that contemplated in the law, a problem that was only partially mitigated by assistance from the overworked and undermanned territorial game wardens. When Frank Been visited Katmai in 1940, he observed that hunting and trapping was carried on there "with the same freedom as . . . in the public domain." Excavation of pumice from beaches at Katmai occurred in the late 1940s and early 1950s. [53] Generally, however, because of the remoteness of the areas and the relative lack of population and developmental pressures, administrative neglect of the Alaska parks and monuments was not as serious as it might have been. [54] External factors, not design, served to buffer the areas from serious and irreversible encroachment and damage. However much Alaskans might oppose withdrawal of public lands by executive action, they were equally adamant, once those lands were withdrawn, that they should be developed and made available for use. Failure to more actively manage the Alaska parks and monuments did serve to reinforce perceptions in Alaska that the federal government was insensitive to the needs of Alaskans. [55] It created a situation, moreover, in which politicians could seriously propose abolishing an area of the unquestioned significance of Katmai National Monument. [56] It did serious damage to the image of the National Park Service in Alaska, and made it more difficult, into the 1970s, for the Service to muster support for its efforts to bring additional areas in Alaska into the National Park System. [57] National Park Service officials were not unaware of the problems the Service faced in Alaska. From the mid-1940s, successive directors did try to improve the situation there. These efforts, which were often the result of urging from NPS officials who had a special interest in Alaska, were sporadic until the mid-1950s and did not, until the mid-1960s, result in any reappraisal of the Service' s role in Alaska. Until the 1950s, moreover, these efforts to improve administration of the Alaskan areas, such as that Director Newton B. Drury recommended in 1946, had little apparent effect on the situation there. [58] C. National Park Service Studies in Alaska, 1937-1946 Although the Service did not more actively manage the existing areas in Alaska before the 1960s, it nevertheless succeeded, over the years, in building a basic body of knowledge about Alaska and the park values there. Before the early 1950s, this did not result from any well-conceived program initiated by the Service itself, but resulted primarily from a number of proposals to set areas in Alaska aside as national parks and monuments. As often as not these proposals came from interested parties outside the Service. Each proposal for inclusion of a new area in the National Park System, whether it came from within the Service or outside, required some kind of study. Although the Service and its supporters were unable to bring additional areas into the system before the 1970s, the result of their efforts would be the accumulation of a body of knowledge about Alaskan lands that, while by no means comprehensive, would provide a firm base of information on which to build when the Service did assume a more active role in Alaska. A number of the areas suggested as potential national parks surfaced, in one way or another, time and again over the years. One such area was Admiralty Island in Southeast Alaska, proposed as early as 1928 as a national park to protect the Alaska brown bears that inhabited the area. [59] Park Service officials inspected the area in 1932, 1938, and again in 1942. Each time they concluded that while the island was an area of great beauty, it did not meet criteria necessary for inclusion in the National Park System. [60] Nevertheless, the issue was raised so many times that in 1963 Conrad L. Wirth wrote, in exasperation, "we have said 'no' on Admiralty more times, I believe, than there are . . . Alaska brown bears!" [61] Wirth exaggerated only slightly. Despite the negative reports, the issue was raised again in 1947, 1948, 1950, 1955, 1962, and would not be finally settled until 1977. [62] A second area that received consideration again and again, but never found its way into the system was Lake George, an interesting self-dumping glacial lake located forty-four miles northeast of Anchorage. The area was first proposed in 1937. A 1939 NPS report indicated that, although Lake George was an interesting phenomenon, it lacked the national significance required for national park or monument status. Nevertheless, the Service studied Lake George in 1958, 1961, and 1967, when the Anchorage Times proposed park status for the area. The suggestion was rejected each time, but on July 26, 1968, Lake George did become the first national natural landmark in Alaska. [63] More important, in that it did become part of the system, were efforts to include various portions of the Wrangell-Saint Elias Mountains region, an area along the Canadian border that contains some of the highest mountains in North America. [64] The Forest Service had recommended establishment of a national monument in the Wrangells as early as 1908, and Senator Lewis Schwellenback of Washington and Alaska Delegate Anthony Dimond proposed establishing an international park on the Alaska-Yukon-British Columbia border in 1937. Park Service interest in the Wrangell-St. Elias region, however, dates to 1938 when Ernest Gruening, then director of the Interior Department's Division of Territories and Island Possessions, suggested that the Service survey the Chitina Valley for possible inclusion in the system. [65] In August of that year, Gruening, along with Harry J. Leik, superintendent of Mount McKinley National Park and NPS Chief of Forestry John Coffman, surveyed the area. They concluded that the area measured up to the very highest of national park standards, stating that "among our national parks, it would rate with the best, if in fact it would not even exceed the mountain scenery of existing national parks." [66] "Alaska Regional National Park" and "Panorama National Park" were two of the names suggested for the area roughly bounded by the Wrangell Mountains on the north, Chugach Mountains on the south, Copper River on the west, and Canadian border on the east. The new national park would have combined recreation, scenic values, and continued development—particularly mining. In an addendum to the Coffman-Leik Report, Gruening proposed the immediate establishment of a 900-square-mile Kennicott National Monument, to include the Kennicott Glacier and Kennicott mine site. [67] By 1940 success for Gruening's proposal seemed certain when Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes forwarded a draft proclamation to President Roosevelt. Roosevelt refused, however, to sign the proclamation, citing "the emergency with which we are confronted." [68] Later that year, a negative study by Frank Been effectively killed the Kennicott National Monument proposal. [69] A significant aspect of the Wrangell/Saint Elias proposal was continued interest, on both the part of Canadians and Americans, in creating a great international park in the area. This idea was first raised in 1938, came up again in 1944 in response to a Canadian withdrawal of some 10,000 square miles on their side of the border, and was implicit, or explicit, in various expressions of interest in the area raised in 1952, 1964, 1965, 1966, 1967-68, and 1969-72, when the Service conducted intensive, but ultimately unsuccessful, negotiations with Canadian officials regarding establishment of an international park. [70] Surveys of these, and other areas across Alaska—Mt. Shishaldin, Kenai, Amagat Island, for example—were of unquestionable importance in building a body of knowledge about Alaska. They were, however, piecemeal. The first opportunity to go beyond the narrow limits of a specific area was associated with the Alaska Military Highway (Alaska Highway). In 1942 the Service had been asked to provide technical comments on the proposed military highway. In 1943-44 Service personnel undertook a survey of the scenic and recreational potential of a forty-mile wide strip along the entire length of the highway in Alaska that had been withdrawn by Secretary Ickes in an effort to establish a common conservation approach with the Canadian government. [73] President Roosevelt authorized $50,000 for the project, and in June 1943 a four-man-team headed by Senior Land Planner Allyn P. Bursley began work on the project. [74] In December 1944 Bursley and his group presented the results of their work, which included a survey of all roads in Alaska. While concluding that no areas along the military highway need be withdrawn for park purposes, the study team argued that the Federal Government, but not necessarily the National Park Service, had a responsibility for providing accommodations for visitors, and fostering travel in Alaska. To this end they proposed a broad plan that included interpretive signs, construction of overnight facilities along the highway, and a full-scale tourist facility at Mentasta Lake. [75] Possibly the $4,472,000 estimated for carrying out the proposals proved prohibitive, but for whatever reason, nothing came of the survey team's proposals. The Department of the Interior did consider directing the Park Service to construct a model tourist facility in 1946, but no evidence to suggest this was accomplished was uncovered. [76] D. A New Beginning: The NPS in Alaska, 1950-1960 Although little concrete came from the survey of Alaska's roads, it did serve to whet the appetites of some within the Service. George Collins and others in the Service began to argue that under the Park, Parkway and Recreation Act of 1936 the Service had an obligation to learn as much as possible about the territory and the recreational resources there. Accordingly, in 1950 the Service initiated the Alaska Recreation Survey, a project that would not be completed until 1954, the purpose of which was to develop long-range plans that would provide guidance for the Service, as well as others, in

Funded for $10,000 in 1950, with additional monies coming in succeeding years, the Alaska Recreational Survey team, headed by George Collins, chief, state & territorial division, Region 4, spent the next several summers in Alaska, learning as much about the territory as possible and inventorying the resources there. In 1950, for example, one group conducted a survey of Southeast Alaska, then moved on to study Kodiak Island and Katmai National Monument, while a team of historians traveled up the Alaska Highway, checking into museums and libraries in Canada and Alaska. [79] The survey team quickly discovered that not only was the Park Service's knowledge of Alaska superficial, but that any detailed knowledge about the land was surprisingly scanty. The Alaska Recreational Survey, as a result, contributed not only to the Service's understanding, but made major contributions to a more general body of knowledge about Alaska. Over the next several years the Alaska Recreation Survey sponsored, among other things, a comprehensive study of the economic aspects of tourism in Alaska, the first comprehensive geological survey of the territory, a thorough biological study of Katmai, a preliminary geographical study of the Kongakut-Firth River area in Northeast Alaska, and developed a broad-scale recreation plan for Alaska. [80] In 1952, moreover, the team studied and first proposed establishment of an Arctic Wilderness International Park on the northeastern Alaska-Yukon border, an area that became the Arctic Wildlife Range on December 6, 1960. [81] Elsewhere within the Service, evidence of a growing interest in Alaska was evident in the early 1950s. In 1953 Grant Pearson, superintendent of Mount McKinley National Park, published his study of the history of that park, and in 1954 John Kauffmann, a NPS planner with a special interest in Alaska, produced boundary histories of Katmai, Glacier Bay, and Mount Mckinley. In 1952 Arthur A. Woodward completed "A Preliminary Survey of Alaska's Archeology, Ethnology, and History," a study supplemented in 1961 when NPS historian Charles Snell visited some forty-five historic sites across Alaska on behalf of the Historic Sites Survey. [82] The survey of historic sites in Alaska was part of a more general, nationwide survey that had been initiated in 1937 and suspended during World War II . Funding for the program after 1956, including the studies done in Alaska, came from Mission 66—a broad program initiated by NPS Director Conrad L. Wirth that was designed to upgrade all facilities and services in the National Park System. [83]

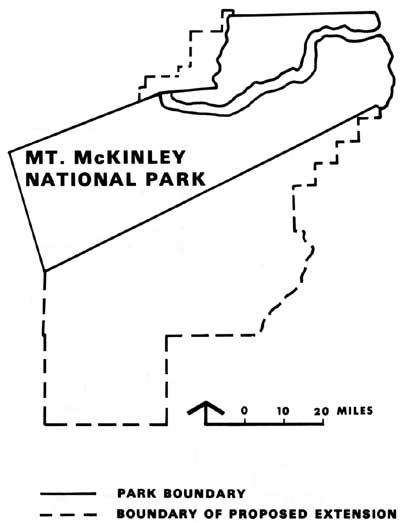

Money from Mission 66 provided, in some cases, the first development money in the existence of the Alaska areas. In three years, from 1957, when the program got underway, until 1960 some $12,942,400 went to the four Alaskan areas [84]. Mission 66 provided funds for vastly-needed improvement of the park road at Mt. McKinley. Work began on a headquarters, residential, and operational facilities at Katmai, and two projects long urged by Alaska's newly-elected Senator Ernest Gruening—a tourist facility at Glacier Bay's Bartlett Cove, and a controversial jeep trail into Katmai's Valley of the Ten Thousand Smokes—were completed. [85] Mission 66 was not, however, merely a construction and development program as many believe. Among other things, it provided funds for preparation of boundary revision studies; a nation-wide plan for parks, parkways, and recreation areas that included an inventory of existing areas and proposals for new areas, and planning for the "orderly achievement of a well-rounded system." [86] In 1960, again as part of a broader, nationwide effort, George Collins hired Roger Allin, a long-time Fish and Wildlife Service employee in Alaska, to develop a general recreation plan for Alaska that would identify areas that should be protected by the federal, state, or local governments. The material Allin developed, along with similar recreation plans and proposals for additions to the National Park System prepared by staffs of all regional offices, was compiled in the 1964 NPS publication, Parks for America. [87] In terms of future national parks in Alaska, Parks for America proved a conservative document that listed only two areas as potential national parks—Saint Elias-Wrangell Mountains (800,000 acres) and Lake Clark Pass (330,000). [88] Additionally, Allin, along with Theodor Swem, a NPS planner then attached to the Washington office, participated in a joint federal-state survey of the Wood-Tikchik area in southwestern Alaska in 1962. While in Alaska they also made an initial reconnaissance of Round Island, looked at Lake George and Lake Clark, and conducted a brief boundary survey of Katmai. [89] The next year Swem returned to Alaska, accompanied by Sigurd F. Olson, to inspect potential areas that included Wood-Tikchik, Lake Clark, Skagway, and proposed boundary extensions at Mount McKinley. [90] Mission 66 was unquestionably a major step forward for the National Park Service in Alaska. For the first time money had been made available for tourist facilities that would begin to make Katmai and Glacier Bay national monuments more accessible. Roger Allin had been able to collect much of the available information to develop a plan for protecting a number of critical areas across the state. Under Mission 66 the Service had begun to take the necessary first steps to correct past inaction, and lay the foundation for a much broader effort to follow. E. The National Park Service in Alaska, 1964-1971 Mission 66 was a nationwide program. What it did not do in Alaska was stimulate a broad reappraisal of the Service's role there, or bring about significant changes in approach to management of NPS areas. [91] Despite the very real accomplishments of Mission 66, when John Kauffmann traveled to Alaska in 1964 to participate in making of a Park Service film about the Alaskan parks, he was appalled by what he observed of the NPS presence in the state. [92]

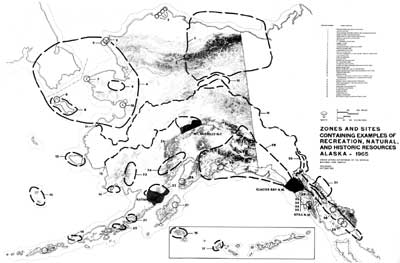

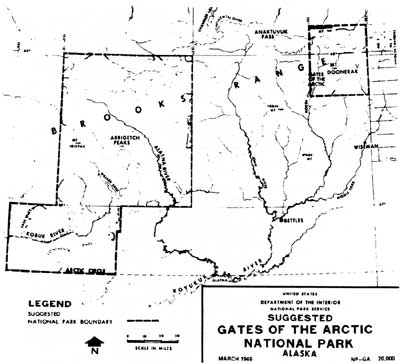

In a stinging rebuke that was circulated widely in the Service's Washington office, Kauffmann wrote eloquently of opportunities lost, of a failure to make adjustments to the Alaska environment, and of failure to develop any well-thought-out concept of what the Service's mission in Alaska should be. The Service had failed, even, to make its presence known in the state. "Indeed," he wrote, "after more than forty years as an organization, the Service is the Cheechako of all federal agencies at work in Alaska." [93] Kauffmann's call for a reappraisal of the Service's role in Alaska came at a most auspicious time. Changes were taking place in the Service, changes that would have a significant effect on the National Park System in Alaska. George B. Hartzog, Jr., the dynamic, forceful new director who had replaced Conrad L. Wirth on January 8, 1964, was determined to build on Wirth's many achievements, and made protection of the "surviving landmarks of our national heritage" as a primary goal of his administration. [94] Hartzog recognized early on that if any significant growth of the park system were to occur, that growth would have to be in Alaska. [95] Hartzog chose Theodor R. Swem, a planner with a life-long interest in Alaska as his assistant director for cooperative activities, with responsibility for planning and new area studies. In that position Swem would be able to use his influence to obtain greater funding for the Service's efforts in Alaska than ever before, and to direct a more comprehensive planning program for Alaska than previously envisioned. At the regional level, John Rutter, first as director of the Western Region and later of the Pacific Northwest Region, would make improvement of the NPS operation and facilities in Alaska an important part of his program. [96] In November 1964 Hartzog appointed a special task force to prepare an analysis of "the best remaining possibilities for the service in Alaska." [97] The group, made up of the most knowledgeable "Alaska hands" available, took the broadest possible view of their assignment, and their report, Operation Great Land, was a broad appraisal of the Service's performance in Alaska, with recommendations for the future. [98] As had John Kauffmann the year before, the Task Force was most critical of the Service's past actions in Alaska. With full knowledge of the potential of Alaska, they wrote, the Service had done little, "except give lip service to the broad concept." Pointing out that total visitation to the Alaska areas was only a "pitiful" 42,131 in 1964, the Task Force warned that neither Alaskans, nor Americans generally would support the Service's program in Alaska unless major steps were taken to correct past deficiencies. Concluding that "the time has come for action, not words," the group recommended that the Service take a far more active role in Alaska to establish a program of investigation, study, planning, and development and operations. Among the specific recommendations were development of a broad history program; establishment of an Alaska office in Alaska; and cooperative ventures with Canada, state, and other federal agencies in Alaska. Finally, the group made a comprehensive evaluation of potential areas in Alaska, identifying thirty-nine zones and sites across the state which contained recreation, natural, and/or historic values. These zones and sites, which are shown in Illustration 2, included many areas that the Service had long been interested in, and which would be given protection in the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980. [99] Many of the Task Force's observations had been made before. Park Service officials had called for creation of an Alaska office since 1946. Theodor Swem and John Kauffmann had reached similar conclusions regarding the NPS presence in Alaska in 1962 and 1964, and had recommended some of the same corrective actions. [100] The following year Roger Allin would issue a similar, if somewhat more conservative, proposal in his "Alaska, A Plan for Action." [101] Additional support came from the Federal Field Committee for Development Planning in Alaska. The committee saw parks as having a vital role in the development of Alaska's economy, and called upon both state and federal governments to look at Alaskan parks, and to establish an "entire park complex" that would "meet the needs of the American people." The committee recommended establishment of a national park in Arctic Alaska, and identification of other areas for future designation. [102] Perhaps the general tone of the Operation Great Land struck Director Hartzog as being too aggressive. Whatever the reason, in what was surely an uncharacteristic display of reticence, he decided not to circulate Operation Great Land, explaining:

Whatever his reasons for refusing to circulate Operation Great Land, George Hartzog's decision certainly did not reflect any opposition on his part to an increased NPS presence in Alaska. Over the next several years he took steps to reverse a long-standing funding imbalance and, although budget cutbacks were forcing the Service to reduce visitor hours and close campgrounds elsewhere, more money went to Alaska. [104] In 1966, moreover, he considered the possibility of developing a program for the state, based "upon a practical application of the [Collins] report." [105 ] This suggestion was not, apparently, pursued further. Nevertheless, a number of recommendations in the Task Force's report were implemented in some form over the next several years as the Service moved to expand its role in Alaska. In the summer of 1965, for example, the Secretary's Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings, and Monuments toured Alaska with George Hartzog, Theodor Swem, and others, on a trip that secured important support for the Service's effort to expand and improve its operations in the state. [106] Later, in 1967, in a meeting with Governor Walter Hickel, Director Hartzog made an effort to initiate a series of cooperative planning ventures with the state of Alaska at Wood-Tikchik, Alatna-Kobuk, and Skagway. Although Hickel appeared to be most receptive to Director Hartzog's suggestions when they met, he followed through only on the Skagway study. [107] By August 1965, moreover, Director Hartzog had decided to open a NPS office in Anchorage. The Washington office had begun to screen applications for the position of park planner in Anchorage in November of that year, and by April 1966 the Service had established an office in Anchorage in the person of park planner Harry Smith. [108] In December 1966 Bailey Breedlove, a landscape architect from the Service's National Capital Regional Office replaced Smith in the Anchorage Office, and by May 1967, the Alaska Field Office had a permanent staff of three—Breedlove, Dick Prasil, a biologist from the Western Regional Office, and a secretary. [109] Administratively, the Alaska Field Office functioned as an organizational division of Mount McKinley National Park. As such, the staff in Anchorage was under the direct supervision of the superintendent of Mount McKinley National Park, although it was given unusually wide latitude in carrying out its duties. The superintendent of Mount McKinley reported to the regional director in San Francisco. In 1969 the Service created a northwest district office in Seattle with responsibility for Alaska, and by early 1971 a fully-staffed and operational Pacific Northwest Regional Office, also in Seattle, had assumed responsibility for Alaska. [110] The superintendent of Mount McKinley was, in addition, the state coordinator for Alaska. In this capacity, he was the Service's representative for all statewide programs and liaison with the state government and other federal agencies. [111] Personnel assigned to the New Alaska Field Office would play an important role in an intensive planning program initiated in 1967 by Ted Swem's Washington Office of Cooperative Activities. Over the next three years, planning teams, led by Merrill Mattes, a historian in the office of resources planning in the Service's newly created (1966) San Francisco Service Center, prepared master plans for existing areas, and added to the Service's knowledge of Alaska generally, as they studied potential additions to the system. [112] In August of 1967 a team traveled to Attu Island, where they completed a study of alternatives. [113] In 1968 they prepared a master plan for Mount McKinley National Park that recommended, as had others before them, a two-unit addition of 2,202,238 acres. [114] Later that year he team traveled north, where they conducted the initial NPS study of the south slope of the Brooks Range. In Kobuk-Koyukuk: A Reconnaissance Report, Mattes and his group recommended establishment of a two-unit "Gates of the Arctic National Park," that would protect some 4,119,000 acres of the finest remaining wilderness in America. [115] Master planning work went on, additionally, at Glacier Bay and Katmai. Planning teams studied a proposed Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park at Skagway, updated a 1965 feasibility study of the Erskine House at Old Kodiak, and in 1969 investigated ways of preserving the heritage of Alaskan Natives through creation of cultural centers. [116] By the mid-1960s, moreover, the Service began to evaluate a number of Alaska sites under the National Landmark Program. On May 3, 1967, for example, Assistant Director Swem made $20,000 available for studies of potential natural landmarks. [117] Richard Prasil, who coordinated the program in Alaska, announced that the University of Alaska had agreed to conduct evaluations of seven potential areas that included Walker Lake and the Arrigetch Peaks in the Brooks Range. Ellis Taylor contracted to study six volcanic areas, including Aniakchak Crater and Mount Veniaminof, and the Service undertook studies of a number of other areas, one of which was the Imuruk Lava Fields. [118] The natural landmark studies in Alaska were conducted in a haphazard manner. Rather than following the established procedures of conducting a state or regional survey of themes, followed by site evaluations, the Alaska studies were conducted on an area by area basis. [119] No broad survey was attempted, in fact, until the early 1970s, when the Service published a study of potential natural landmarks in the Arctic Lowlands. [120] Nevertheless, by 1968 fifteen sites in Alaska, including the Arrigetch Peaks, Walker Lake, Lake George, and Aniakchak Crater had been recognized as registered National Natural Landmarks. Evaluations of sites all across Alaska conducted under the program would give NPS planners, as well as those from other agencies, valuable information regarding significance of resources needed in making withdrawals mandated by the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971. [121] The Service's studies and surveys of potential park areas in Alaska had been piecemeal. It was only in the 1965 report of George Collins's task force that any attempt to make a comprehensive analysis of potential national parks in Alaska was undertaken. By the end of the 1960s, however, and into the 1970s, a number of efforts to make a comprehensive survey of potential national parklands in Alaska were underway. One such effort was undertaken by Richard Stenmark, a NPS employee, in his capacity as executive secretary of Secretary of the Interior Walter Hickel's fourteen-member Alaska Park and Monuments Advisory Committee, established in 1969 to give advice on development and potential parks in Alaska. [122] In addition, the Federal Field Committee for Development Planning in Alaska worked on a plan of action anticipated to launch a "full scale comprehensive joint Federal-State Land Use and Classification Plan for Alaska." [123] At the same time, following publication of the Park System Plan in 1970, the Park Service began an inventory of the National Park System to determine how adequately the existing areas illustrated the human and natural history of the nation, and to identify areas that would fill in any gaps in the system. By November 17, 1971, the Alaska Office had completed a proposed "National Park System Alaska Plan" that listed historical, natural, and recreation areas in the state for further study for possible inclusion in the National Park System. The list, which was essentially that prepared independently by Richard Stenmark for the use of the Alaska Parks and Monuments Advisory Committee, included most areas that would be withdrawn by Secretary of the Interior Rogers C. B. Morton pursuant to terms of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971: Historical Areas:

Natural Areas:

Recreational Areas:

The Service significantly increased the scope of its activities in Alaska during the 1960s, and undertook a comprehensive effort to identify, by theme, potential additions to the National Park System. Efforts to bring additional areas into the system in the decade met with almost universal failure, however, save for a small, 94,000-acre addition to Katmai National Monument in 1969. In 1965, for example, Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall recommended legislation to convert Glacier Bay National Monument into a national park. Although seconded by Senator Ernest Gruening, who expressed interest in introducing such a bill, no action would be taken. In 1969-70, Senator Ted Stevens indicated an interest in gaining park status for a portion of Misty Fjords and the Rudyard Bay-Walker Cove area. In 1969 Senator Mike Gravel spoke of establishing a Kodiak National Historical Site, and Representative John Saylor introduced the first of several bills to extend the boundaries of Mt. McKinley and to establish Gates of the Arctic National Park. [125]

In 1968, taking advantage of an entree arranged by Dr. Carl McMurray of Governor Hickel's staff, the Service undertook negotiations with the city of Skagway and Canadian officials for creation of an international Klondike Gold Rush Historical Park, an effort that would include a widely publicized joint Canadian-American hike over the Chilikoot Trail in September 1969. [126] In 1969, moreover, the Service initiated a three-year-long dialogue with Canadian officials regarding an international park in the Wrangells-Saint Elias region. Successful conclusion to these discussions seemed to be within reach in 1972 when the Service completed a conceptual master plan, an environmental impact statement for the proposed Alaska National Park, and prepared the draft legislation necessary. However, just as the park that some had dreamed of for years seemed to be on the verge of reality, the effort foundered. [127] No failure could have been more disappointing to Park Service officials, however, than the aborted effort to establish more than 7,000,000 acres of new monuments in Alaska and elsewhere during the closing months of President Lyndon B. Johnson's administration. [128] The project—named "Project 'P'"—was conceived of by Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall in the fall of 1968 as President Lyndon Johnson's "parting gift for future generations." [129] For Park Service officials it offered an unprecedented opportunity to add areas to the system. By early December fifteen original areas—six of them in Alaska—had been narrowed to seven. [130] Proclamations, as well as support data, had been prepared for Mount McKinley (2,202,328 acres adjacent to the park), a two-unit, 4,119,013-acre Gates of the Arctic, Katmai (a 94,547-acre western addition), Arches (49,943 acres), Capital Reef (215,056 acres), Marble Canyon (26,080 acres), and Sonoran Desert (911,697 acres). [131] Despite some four months of concentrated effort on the part of a number of people in the Park Service, other agencies, and Interior Department staff, President Johnson balked at the very last moment and refused to sign all the proclamations prepared for his signature. [132] The reasons for his refusal remain the subject of controversy. Among the reasons advanced are a sensitivity on the part of President Johnson to the prerogatives of Congress in the matter of setting aside public lands, his petulance over the premature release of information by Secretary Udall, Lyndon Johnson's ego, a concern that last-minute activity not bind successors, and presidential anger over Secretary Udall's failure to brief Representative Wayne Aspinall, the powerful chairman of the House Interior and Insular Affairs Committee, as he indicated he had. [133] Whatever the case, and the merits of the arguments are too complex to be examined here, President Johnson finally signed proclamations for Arches, Capital Reef, and Marble Canyon. The only Alaska area included was the 94,547-acre western addition to Katmai, an area that included the western end of Naknek Lake. [134] By the end of the 1960s and into the 1970s, the National Park Service had made substantial progress in its effort to reverse the long-standing neglect of Alaska parks. The existence of an Alaska office in Anchorage gave the Service a presence in the state that had been missing. Building on studies that went back to the 1930s, the Service had compiled an impressive body of knowledge about Alaska and the park resources there, and had identified a considerable number of areas that met criteria for inclusion in the National Park System. For a variety of reasons, however, NPS officials had been unsuccessful in their efforts to bring additional areas into the system, save the small, 94,000-acre tract added to Katmai National Monument. Coincidentally, however, a bill was working its way through Congress, one that on the face of it had little to do with national parklands. Yet, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of December 18, 1971, would be the vehicle that would provide for parks in Alaska almost beyond the wildest dreams of anyone in the National Park Service. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

williss/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 29-Feb-2016