|

National Park Service

"Do Things Right the First Time": Administrative History: The National Park Service and the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980 |

|

|

Chapter Two: A. Statehood Grants The Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980 provided for 43,585,000 acres of new national parklands in Alaska; the addition of 53,720,000 acres to the National Wildlife Refuge System; twenty-five wild and scenic rivers, with twelve more to be studied for that designation; establishment of Misty Fjords and Admiralty Island national monuments in Southeast Alaska; establishment of Steese National Conservation Area and White Mountain National Recreation Area to be managed by the Bureau of Land Management; the addition of 56,400,000 acres to the Wilderness Preservation System, and the addition of 3,350,000 acres to Tongass and Chugach national forests. It was, many believe, the most significant single piece of legislation in the history of conservation in the United States. In Alaska it represented, too, a significant step in the disposition of public lands in the state. [1] In 1958, when Congress passed the Alaska statehood bill after nearly two decades of lobbying by Alaskans, federal land reserves in the new state totaled 92,400,000 acres. Twenty million acres were in national forests, 23,000,000 acres in a naval petroleum reserve above the Arctic Circle, more than 27,000,000 acres in power reserves, 7,800,000 acres in wildlife refuges, and in excess of 7,500,000 acres in national parks and monuments. The federal government was, additionally, trustee for more than 4,000,000 acres of Indian reservations. Only 700,000 acres in Alaska had been patented to private individuals, while another 600,000 acres were pending. The unreserved public domain consisted of 271,800,000 acres. [2] Two questions that emerged in the debate over Alaska statehood are particularly relevant here. What could be done, Congress asked, to guarantee that the new state would survive economically? A second, and even more vexing question, was one Congress had avoided in the past—what to do about the land claims of the Native peoples of Alaska. In an effort to provide the new state with a sound economic base, Congress proved to be generous by any standard. Alaska received the right to select 102,550,000 acres from the public domain, 400,000 acres from national forest land in Southeast and 400,000 acres from the public domain for community expansion, and 200,000 acres of university and school lands to be held in trust by the state. Congress also confirmed earlier federal grants to the territory that amounted to 1,000,000 acres. [3] Congress gave Alaska the right to select an area of land roughly the size of California—larger than that given all the other western states combined. [4] Moreover, Alaska could select mineral lands as part of its statehood grant, although the mineral rights transferred would be unalienable—that is they could be leased, but not sold. Finally, Congress gave Alaska a larger share of the mineral lease revenues on the public domain than any other state. [5] Natives—Aleuts, Eskimos, and Indians—made up some twenty percent of the population of Alaska in 1960. Although they were a minority of the population as a whole, they did constitute a majority in some 200 communities and villages spread across the face of rural Alaska. A considerable majority lived a subsistence lifestyle similar to that of their ancestors. Congress had, according to a 1963 report, sidestepped the question of their rights in the land for more than seventy years. An added difficulty Congress faced during the statehood debate was the existence of three Alaska cases then pending before the Court of Claims. [8] The Natives were unorganized in the late 1950s. Most lived in small, isolated villages spread across Alaska. As a result, the question of their rights in the land was not one that Congress dwelled on during a statehood debate. After some discussion, the statehood act did include a provision in the law that merely reaffirmed the right of Congress to settle the Alaska Natives' claims in the land:

B. Native Land Claims As Alaska state officials undertook the selection of land granted under the Statehood Act they faced a number of problems. In the first place, knowledge of what a large portion of Alaska's lands contained was still relatively superficial, something that made selecting lands that would provide a sound economic base obviously difficult. State officials admitted, moreover, that they did not have the financial wherewithal to provide adequate management for the lands. The statehood act allowed state officials, finally, twenty—five years to make selections. [10] As a result, state officials moved slowly in selecting land during the 1960s. By the end of that decade they had selected less than a quarter of their entitlement--some 28,000,000 acres, chosen in hopes of bolstering the state's economy, most notably in the oil, gas, and mineral industries. [11] Nevertheless, almost as soon as state officials began to divide rural Alaska, it became apparent that the failure to have addressed the question of the land claims of Alaska Natives in the statehood act virtually assured almost continual conflict. The state's efforts to select the most productive lands clashed, in many instances, with the Natives' need to use the land to maintain their traditional lifestyles. In 1961, for example, the Department of the Interior's Bureau of Indian Affairs filed protests over state selections on behalf of four Native villages that claimed about 5,800,000 acres of land near Fairbanks. State officials had already selected and filed for 1,700,000 acres of land near the Athabascan village of Minto, which they intended to develop as a recreation area for Fairbanks residents. State officials believed, as well, that the area possessed the potential for future oil and gas development. [12] The villagers of Minto, who were not consulted in the proposal, depended upon that land for their livelihood. They protested, recognizing that state plans to develop the area threatened their way of life. Other Native villagers across Alaska soon found themselves confronted by similar challenges. In 1965, for example, villagers in Tanacross, a small village near Fairbanks, were outraged when they discovered that the state intended to sell lots around their traditional fishing ground at George Lake to visitors at the Alaska booth at the New York World Fair. [13] Threats to the Native lifestyles from state land selections predominated in the early 1960s. They were not, however, the only problem Alaska Natives faced. In 1961, for example, the Inupiat Eskimo artist Howard Rock discovered that the United States Atomic Energy Commission planned to detonate a nuclear device at Cape Thompson on the northwest coast. The purpose was to create a harbor that would be used for shipment of minerals. Villagers at Point Hope, Kivalina, and Noatak, however, had long used the Cape Thompson area for hunting and egging. [14] In 1963 Natives along the Yukon River were outraged when Senator Ernest Gruening urged Congress to fund the huge Rampart Dam hydroelectric project of the Yukon Flats Region in northcentral Alaska. Especially galling to Natives in the area was Gruening's claim that the 10,000-square-mile lake that would be created by the dam would flood only a "vast swamp uninhabited except for seven small Indian villages." [15] When Congress debated Alaska statehood, the Alaskan Natives had been an unorganized, seemingly helpless group who had little voice in the decisions that would shape their future. By the mid-1960s, however, a growing self-awareness fostered by the recognition that their very way of life was in danger had galvanized the Natives. Native associations sprang up all over Alaska. After Howard Rock published the first edition of Tundra Times in 1962, the Natives had a common voice. When the Alaska Federation of Natives brought the village and regional associations together in 1966, a organized Native community emerged as a potent political force in Alaska. The question of their land claims could be ignored no longer. [16] In 1963 Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall appointed a three-person Alaska Task Force on Native Affairs to study the entire question of Alaska Native land claims. Secretary Udall's action followed a request by some 1000 Natives from twenty-four villages in the Alaska Peninsula, Yukon River Delta, Bristol Bay area, and Aleutian Islands to impose a freeze on all transfers of land ownership in their villages until land rights could be confirmed. [17] Secretary Udall, it is obvious, ignored the request for a freeze on land transfers. The recommendations presented him by the task force he appointed would be unacceptable to Native groups as well—prompt granting of up to 160 acres to individuals for homes or fish camps, and hunting sites; withdrawal of "small acreages" for village growth; and designation of areas for Native use, but not ownership for traditional food-gathering activities. Nevertheless, the Interior Department had signaled that it, too, believed the time had come for settlement of Alaska Native land claims. [18] Three years later, the newly-formed Alaska Federation of Natives made a similar request for a freeze on land transfers. In what was in part a recognition of the growing political power of the Alaska Natives, Secretary Udall stopped the transfer of all lands claimed by Natives until Congress had time to act on the matter. [19] The extent of the moratorium depended, of course, on number and extent of claims. By May 1967 thirty-nine claims ranging in size from the 640 acres claimed by the village of Chilikoot to 50,000,000 acres claimed by the Arctic Slope Native Association had been filed. In all, because of overlapping claims, about 380,000,000 acres--an amount greater than the land area of Alaska--was affected by the freeze. [20] Although some, Senator Gruening, for example, preferred that the question be resolved in the courts, most recognized that the problem of Native land claims demanded a legislative solution. As early as July 1966 the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Bureau of Land Management had prepared a draft of the bill "dealing with Alaska Natives land problems." [21] The first bills, however, were not introduced until the summer of 1967. In that year, one sponsored by the Department of the Interior, the other by the Alaska Federation of Natives, would have authorized a court to determine compensation for lands lost. The AFN bill would have allowed the court to award title to lands with no acreage specified, while the Interior Department's bill would have authorized a maximum of 50,000 acres in trust for each village. [22] Not until four years later, under considerably different circumstances would a settlement be produced. In his delightful book Coming into the Country, John McPhee wrote that the Alaska Natives Claims Settlement Act was

Perhaps. Joe Upicksoun, president of the North Slope Native Association advanced another explanation, however, when he told Native leaders attending a late 1970 Alaska Federation of Natives Conference:

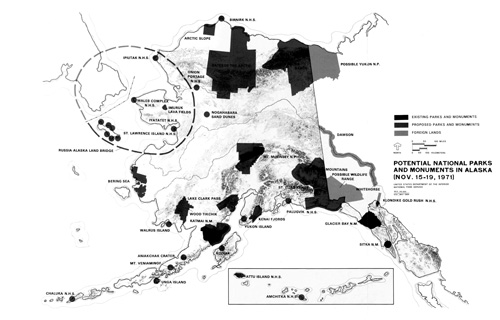

Upiksoun referred, of course, to the 1968 discovery of oil at Prudhoe Bay on the North Slope by Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) and Humble Oil and Refining Company. He might have mentioned, as well, the plans announced by a consortium consisting of ARCO, Humble, and British Petroleum, Ltd. to construct an 800-mile-long hot oil pipeline from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez, a small fishing village on Prince William Sound. The discovery of oil, and the companies' awareness that no pipeline could be laid across the Yukon River Valley until land claims of the Alaskan Natives were settled, soon gave the Natives an invaluable ally in their fight for justice. [24] It is not too much to say, in fact, that concern on the part of Congress and the administration over delays in construction of the Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS) was as much responsible, or more, for passage and final shape of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 than was concern for justice for the Alaska Natives. C. Origins of the National Interest Lands Provision (17(d)(2)) The question of the disposition of the public lands in Alaska was not simply a two-sided one that involved the claims of the Natives and the state. A third element complicating any settlement of those issues was the question of the national interest—how and to what extent should the needs of Americans everywhere be addressed? As indicated previously, individuals and organizations outside the government had worked with staffs of federal agencies in an effort to secure preservation of areas of national, or international significance in Alaska. These efforts were sporadic in nature and did not represent any comprehensive approach to preservation of Alaska's lands. In 1963 the governing council of the Wilderness Society held their annual meeting at Camp Denali, near the border of Mount McKinley National Park. The very location of their meeting signaled a new concern for the future of Alaska's wildlands. A consensus developed during the meeting

Although this call by the Wilderness Society did not lead to an immediate demand for preservation of Alaska lands by conservationists in the "lower '48," by the end of the decade they had taken a more active interest in Alaska. In the state, an informal group of conservationists, many of whom were employed by state and federal agencies, worked to identify significant areas, and developed detailed data on those areas. [26] Following a 1967 trip to Alaska, Sierra Club President Dr. Edgar Wayburn hired an Alaska representative and made saving Alaska wildlands a priority goal of that organization. [27] Particularly after the discovery of oil at Prudhoe Bay, it seemed clear that time was running out if Alaska lands were to be preserved. [28] A growing number of people had become convinced, by the end of the decade, that the vehicle for preserving lands in Alaska, and perhaps the last that would ever be available, was the Alaska Native Claims Settlement bill then working its way through Congress. [29] It would become somewhat fashionable, later, to charge that the inclusion of the national interest lands provision in the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act was a hasty, last-minute affair, written by "outsiders" who did not understand Alaska. Actually, however, it seems apparent that the idea that any settlement of the lands claims of Alaska Natives must also take into account the national interest originated with Joseph Fitzgerald, the far-seeing chairman of the Federal Field Committee for Development Planning in Alaska. [30] As early as 1965-66, Fitzgerald had concluded that economic development could not occur in Alaska until the Native land claims were settled, and that a significant factor in any settlement would be a major involvement of the state and federal governments in the establishment of a "park complex" in Alaska. [31] Fitzgerald approached the Alaska Wilderness Council, asking them to identify areas worthy of preservation. [32] It was, moreover, a member of Fitzgerald's staff—David Hickock—who was actually responsible for inclusion of the first "National Interest Lands" provision in any bill. Hickock, who was natural resources specialist on the Fitzgerald's committee staff, had been borrowed by the Senate Interior and Insular Affairs committee to work on a settlement bill. At his suggestion, a simple provision was added to S. 1830:

On July 15, 1970, the Senate passed S. 1830 by a seventy-six to eight majority. That version of a settlement act included provision similar to that drafted by David Hickock. The Secretary of the Interior was directed to conduct

Although the Senate passed its version of the bill, the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs was unable to reach agreement on a bill. Congress adjourned without completing action on the bill. [35] As the Alaska Natives and their allies regrouped in spring 1971 for what most believed would be the last act in the legislative process of an Alaska Native claims settlement bill, those who had cause to believe that the bill should be broadened to include a provision that would permit the designation of wilderness and provide for the addition to the park and refuge systems mobilized as well. A number of conservation organizations would unite to form the Alaska Coalition to more efficiently work for a national interest lands provision. [36] Earlier the governing council of the Wilderness Society had agreed to become involved in the effort, and by mid-March, Stewart Brandborg had asked the Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs to consider including a five-year, land-use planning program for Alaska. On May 3 Brandborg testified before the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, suggesting, among other things, that they include a provision that would authorize the identification, preservation, and establishment of "areas of national significance as units of the National Park and National Wildlife Refuge and National Wilderness Preservation systems" in any Alaska Native claims settlement. Others in the conservation community would approach Representatives John Saylor and Morris Udall of Arizona to secure their help. By May Congressman Saylor had let it be known that he would offer an amendment that would require land-use planning in Alaska as a part of any settlement. [37] Saylor apparently decided, however, that success in the House would be difficult to achieve and that it would be necessary to secure help in the Senate. He called Nathaniel P. Reed, Assistant Secretary of the Interior, to ask his help in building up support for a national interest lands provision in a senate bill. [38] Representative Saylor also called NPS Director George Hartzog to ask that he approach Nevada Senator Alan Bible, chairman of the Senate Subcommittee on National Parks and Recreation, to enlist his help. Although Hartzog was unable to obtain a commitment from Senator Bible at that time, he did convince the senator to accompany him to Alaska the coming summer (1971) to inspect potential park areas in the state. [39] That August Hartzog, Bible, their wives, and several of Senator Bible's friends traveled in Alaska, viewing potential park areas that included Gates of the Arctic, areas in the Kenai Peninsula, Skagway, and possible extensions to Mount McKinley National Park and Katmai National Monument. [40] Upon their return, Senator Bible promised Hartzog that he would sponsor a park study amendment that fall, and also indicated that he would arrange to be on any conference committee held on the bill should that be necessary. Senator Bible requested, in turn, that Director Hartzog provide him with the appropriate language of an amendment. [41] Director Hartzog understood that the amendment Senator Bible had agreed to introduce would address additions to the National Park System in Alaska with an additional 4,000,000 acres for "minor boundary adjustments" at existing wildlife refuges and national forests. Among the areas Hartzog envisioned in an expanded National Park System in Alaska were a huge Gates of the Arctic National Park that extended north from the Arctic Circle across the Naval Petroleum Reserve to the Arctic Ocean, conversion of Arctic Wildlife Range to a national park that would be eventually a part of a great international park in northeast Alaska-northwest Canada, a large park in the Wrangell-St. Elias Mountains that would adjoin a proposed "Yukon National Park" in Canada, sizeable additions to Mount McKinley National Park and Katmai National Monument, and a number of areas along the western shore that would be part of a Russo-American Land Bridge International Park. Hartzog's proposal to Bible for additions to the National Park System was one of the most far-reaching in the history of the National Park Service. Hartzog thought in much larger terms than nearly anyone inside or outside the Service at that time. His proposal included not only all of the areas identified by the Alaska staff in 1971, but nearly all the "zones and sites" identified by George Collins' special Alaska task force in 1965. In all, Hartzog delineated some twenty-seven potential areas and additions to two existing ones that totaled approximately 75,000,000 acres, an amount that would have tripled the size of the system. [42] Hartzog was apparently concerned that Congress might fail to include a park study provision, however. On August 14, while still in Alaska with Senator Bible, he wrote Secretary of the Interior Hickel, suggesting that he use his authority to withdraw areas in Alaska that were of "prime interest pending their consideration for addition to the National Park System." [43] Hartzog ordered bureau staff to prepare draft language of an amendment for Senator Bible's use. [44] At the same time, others had approached Senator Bible for the same purpose. Harry Crandell, the Wilderness Society's director of wilderness review, discussed the possibility of amending any claims bill with the Senator, as did Dr. Edgar Wayburn and Lloyd Tupling from the Sierra Club, and Stewart Brandborg, executive director of the Wilderness Society. [45] Apparently, Senator Bible received draft language for an amendment from the conservation community. It is certain, too, that he had conferred and received input from Senator Henry Jackson, chairman of the Interior and Insular Affairs Committee, and Senator Gaylord Nelson, both co-sponsors of the amendment. He may have been also in contact with Representatives John Saylor and John Dingell, who was exploring the possibilities of an amendment relating to wildlife refuges. Committee staff rewrote the amendment, regardless of whose draft was submitted to Senator Bible.

It has not been possible to confirm whose language served as a basis for the amendment introduced by Senator Bible. [46] In one sense that question is less important than is the knowledge that a growing consensus demanded that disposition of the public lands in Alaska take into account the national interest as well as state and Native claims. Yet, at the same time, George Hartzog always believed, as he does to this day, that the amendment Senator Bible introduced was intended to be primarily a vehicle for additions to the National Park System in Alaska. [47] There is some evidence to support his belief. In the first place, Senator Bible's interest was, primarily, in parks and recreation. He maintained a close relationship with and seems to have listened closely to George Hartzog on matters regarding parks. In a short discussion with Senator Ted Stevens when he introduced his amendment, moreover, Senator Bible mentioned three areas—a proposed Gates of the Arctic National Park, and extensions to Mt. McKinley National Park and Katmai National Monument. [48] Senator Jackson, moreover, described the amendment that he had co-sponsored as a "park study" amendment. [49] It must be noted, however, that both parks and refuges were included in the amendment introduced. Despite any promises made to George Hartzog, the amendment Senator Bible introduced on November 1 gave no indication of how that land was to be divided, or that a majority would be set aside for additions to the National Park System. Whatever the case may be, there is no question that George Hartzog played a crucial role in securing a national interest lands provision in the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971. He was, without question, instrumental in Senator Bible's decision to sponsor a national interest lands amendment, and that decision was made following the trip the two made to Alaska in August 1971. [50] By the end of September 1971 the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs finally approached the end of an arduous summer s work when it reported H.R. 10367, a settlement bill introduced by Representative Wayne Aspinall of Colorado. Representative Saylor had fulfilled his promise to work for a land use planning amendment, but the committee had soundly rejected his efforts. At the same time, the committee did feel pressure from the conservationists. The bill reported on September 28 included a provision drawn by Representative John Kyl of Iowa that essentially extended the "Udall freeze"—withdrawing all unreserved public lands from entry until the Secretary of the Interior determined they could be reopened. [53] Conservationists considered the Kyl amendment to be inadequate. In a meeting between conservation leaders and Morris Udall, the broad outlines of an amendment that he and Representative Saylor would introduce were drawn. [54] On October 14, 1971, Representatives Udall and Saylor introduced a substitute bill that included the strong national interest lands amendment agreed to in discussions with conservationists. When that bill was referred to the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, Representative Udall introduced a broad land use planning amendment to H.R. 10367 on October 20. It was not, he said, "a simple little amendment." Rather, the amendment, which was introduced on Representative Saylor's behalf as well, was a lengthy and complicated piece of legislation. [55] Of particular concern here, was the provision that directed the Secretary of the Interior to review, identify, and withdraw up to 50,000,000 acres in unreserved land and up to 50,000,000 acres in previously classified lands for study for possible inclusion in the National Park System, National Refuge System, National Resource Lands (multiple-use areas managed by the Bureau of Land Management), National Wild and Scenic Rivers System, and National Forest System. [56] Identification and withdrawal of up to 100,000,000 acres would be completed within six months. [57] Within three years after the passage of the bill, and based upon detailed study of the withdrawn areas, the Secretary of the Interior would recommend study areas, and "adjacent areas which he may deem appropriate," for inclusion in the above systems to the President and Congress. [58] Concerns did exist, despite attempts by supporters of the Udall-Saylor amendment to ameliorate them, that withdrawal of large areas in the state would conflict with settlement of land claims of the Alaska Natives. Others argued that withdrawal of conservation lands would place still another roadblock to construction of the oil pipeline. Earlier the Sierra Club had called its regional representatives to Washington to work for a national interest lands amendment, and, along with the Wilderness Society had set up an intensive lobbying effort on behalf of the Udall-Saylor amendment. [59] They were unable, however, to overcome heavy lobbying by the Natives and their supporters in civil rights organizations, oil companies, state of Alaska, and administration representatives, who helped to defeat the amendment. Nevertheless it was clear that considerable support for some kind of national interest lands provision existed. The amendment failed by a vote of 217-178. The strength of support for the amendment—a switch of 20 votes would have changed the outcome—helped set the stage for up-coming action in the Senate. [60] By the time the Senate took up debate on Senator Henry Jackson's version of a settlement bill (S. 35) on November 1, most of the details of the bill had been generally accepted. As a result, there were no more than a handful of senators on the floor when Senator Bible introduced what he called a "reasonable and non-controversial" amendment:

The Senate Interior and Insular Affairs Committee previously had Secretary of the Interior to included a provision (Sec. 24(c)) in S. 35 that directed the

Senator Bible's "clarifying" amendment answered questions raised as to how that process would work. He added classified lands, as well as Pet 4 and the Rampart Dam Power Site withdrawal to the unreserved lands to be reviewed; provided that the Secretary would report to Congress on the status of the review—size, location, and values of each area—every six months for a period of three years; and extended the withdrawal period for lands recommended to Congress for inclusion in one of the conservation systems from the two years in the committee bill to five years. Senator Bible set no limitation on the amount of land that could be studied or withdrawn. As mentioned, he included only two conservation systems—the National Park System and National Wildlife Refuge System. [63] There were only a handful of senators on the floor when Senator Bible introduced his amendment. It did not prove to be controversial and was not the subject of considerable debate, save a short "collaquy" between Bible and Senator Stevens of Alaska who allowed, somewhat unhappily, that "if I had my druthers, I would not have them in the bill." Nevertheless, Senator Stevens did not oppose the amendment, and it passed by voice vote. Following, the Senate passed its version of the Alaska Native claims settlement bill by a vote of 76-5. [64] Differences between the House and Senate versions of the bill would be worked out in a conference committee. The problem facing the conferees regarding the national interest lands was reconciling the language of the provisions authored by Representative Kyl and Senator Bible. Concern over the national interest, however, was not something that bulked large in the conference. The conferees met nine times between November 30 and December 13. The question of conservation lands did not come up, apparently, until December 9, when the conferees agreed to give the Secretary of the Interior authority to withdraw up to 80,000,000 acres for study for possible inclusion in one of the conservation systems. [65] The conferees added the Wild and Scenic Rivers and National Forest systems to those mentioned in the Bible amendment. As indicated, George Hartzog believed that Senator Bible intended that the majority of land should have gone to the National Park System. Representatives Udall and Saylor argued that the conferees intended that only a minimum amount should go to the National Forest System. It has not been possible to uncover any evidence, however, suggesting that the conferees intended that any of the "four-systems" agencies—National Park Service, Bureau of Sports Fisheries and Wildlife, Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, and Forest Service—would have a priority in terms of size or selection of areas. [66] Questions would be raised, over the next several years, regarding the addition of the National Forest Service in the conference. Inclusion of the Forest Service apparently came from several sources. Staff members of the Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs argued for inclusion of a multiple-use agency in the bill, despite conservationists' arguments to the contrary; staff members of the Federal Field Committee worked for inclusion of the Forest Service hoping that it could be used to convince the Forest Service to release the 400,000 acres provided for community expansion in the Statehood Act in return; and the Udall-Saylor amendment that failed passage in the house provided for additions to the Forest System, although the authors of that amendment did not intend that the Forest Service would be an equal partner. Finally, Ted Stevens, Alaska's senior senator, who was one of the most active and influential members of the conference, insisted on inclusion of that system in an effort, he later said, to include a multiple-use agency that would not "lock up any lands that they might get." [67] The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 was a landmark piece of legislation that is generally considered to be the most generous settlement ever made between the United States government and a group of Native Americans. The act was, moreover, a unique and most interesting experiment that attempted to employ a purely capitalistic invention—the corporation—to protect what is essentially a non-capitalistic, predominantly subsistence life style. The act, at the same time, was complicated, ambiguous, and sometimes contradictory. [68] ANCSA created unique organizations, established relationships between those organizations, defined a variety of land categories, attempted to rationalize the land selection process, and established timetables for disposition of public lands in Alaska. Briefly, and that is all that is possible here, ANCSA granted Alaskan Natives compensation of fee simple title to 40,000,000 acres of land and $925,500,000 for extinguishment of all aboriginal titles, or claims of title to lands. [69] The Act provided for the creation of twelve, with the option later exercised, for a thirteenth, regional corporations and more than 200 village corporations that would share the land and money according to a sometimes complicated formula. [70] Additionally section 14(h) (1) allowed the regional corporations to select cemeteries and historic sites (up to 2,000,000 acres) outside village and regional withdrawals, including land on wildlife refuges and in national forests. [71] And, while the conference committee rejected an explicit statement on subsistence as included in the Senate version of the bill, ANCSA, according to the conference committee report, protected the "Native people's interest in and use of subsistence resources on the public lands" through the withdrawal authority of the Secretary of the Interior. [72] The Act also provided for the creation of a Joint Federal-State Land Use Planning Commission (Section 17(1)(a)). Composed of ten members appointed by the governor of Alaska (4, with the governor or his designee as one of the members), president (1), and secretary of the interior (4), the commission was established to, according to the first federal co-chairman, provide an institution "through which the claims and policies of the three main participants and those of private and public interest can be examined, brokered, and molded into a long-range, balanced land pattern for the state." [73] The conference committee removed the regulatory and enforcement powers given the commission in the senate bill, leaving it only an advisory role. Nevertheless, the functions given the commission were such as to allow it to play a significant role in the upcoming land allocation and planning process. Among the functions outlined were making recommendations to the secretary of the interior regarding withdrawals, advising state and Natives in making selections, and making recommendations to avoid conflict between state and Natives in making selections. [74] The conservation lands provisions—sections 17(d)(1) and 17(d)(2)—immediately became the subject of considerable disagreement, even among some who had participated in the Senate-House conference committee. Section 17(d)(1) had its origins in the Kyl amendment. Known as the public interest lands provision, it was designed to prevent a land rush following revocation of public land order 4582. The purpose, as outlined in the conference committee report, was to permit the secretary of the interior to make the withdrawals directed under section 17(d)(2)(A); and to permit the secretary to determine if there were other areas that should be withdrawn, classified, or reclassified before they were opened to entry:

Section 17(d)(2)—the national interest lands provision—permitted the secretary to withdraw land for possible inclusion in one of the conservation systems, established timetables for withdrawals, study, and congressional action on recommendations:

Efforts to secure justice for the Native peoples of Alaska also set in motion events that would result in passage of one of the most significant pieces of conservation legislation in this nation's history. Passage of an Alaska national interest lands conservation act would not be easy, but would come only after a nine-year struggle. For the National Park Service participation in that effort would have important effects on the Service itself, and would result, too, in a thorough reappraisal of its approach to management of parklands in Alaska. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

williss/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 08-Sep-2016