|

National Park Service

"Do Things Right the First Time": Administrative History: The National Park Service and the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980 |

|

|

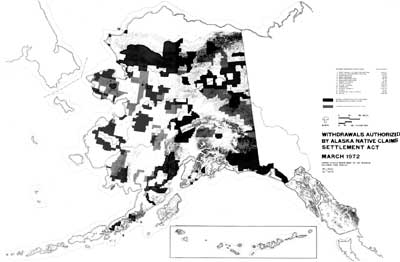

Chapter Three: A. March 17, 1972 (d)(2) Withdrawals In December 1971 Secretary of the Interior Rogers C.B. Morton announced the passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act. In implementing the national interest lands provision therein, he cautioned, we must avoid the mistakes of the past, and "do things right the first time." [1] Interestingly, despite the significance of ANCSA, few in the Interior Department seemed to have closely followed the bill, and considerable uncertainty regarding the ramifications and interpretation of the act existed. At the same time, all quickly recognized that the deadlines imposed upon the secretary of the interior in the act demanded immediate action by all involved. [2] On December 21 Assistant Secretary Nathaniel P. Reed directed NPS Director Hartzog and Spencer Smith, his counterpart in the Bureau of Sports Fisheries and Wildlife, to initiate the process of identifying and prioritizing lands for preservation. They were, he said, to "ignore sovereignty," and report their findings to him by late January. [3] The same day Hartzog appointed Theodor Swem, Assistant Director for Cooperative Activities, to coordinate the Park Service's Alaska effort, promising him an unusual degree of freedom of action. Smith had already dispatched a staff member in his office to Alaska to gather information, and had appointed Robert L. Means to coordinate the efforts of the Bureau of Sports Fisheries and Wildlife. [4] The appointment of Swem to coordinate the Park Service's efforts in Alaska was a fortunate one. He had been deeply involved there since the early 1960s, knew the park resources, and was quick to grasp the opportunity offered the Service in ANCSA. He and Larry Means had worked together previously, moreover, and shared a common approach to Alaska. They quickly developed a working relationship that resulted in an unusual degree of cooperation between their agencies. [5] Although rivalry over areas in Alaska would surface from time to time over the years, particularly at the local level, a spirit of active cooperation between the two agencies dominated the nine-year effort to implement the national interest lands provision of ANCSA. [6] On December 23 Swem notified NPS offices of the Alaska project, the procedure the Service would follow, and the role different offices would play. On December 27 he requested Richard Stenmark of the Alaska Field Office in Anchorage to travel to Washington to work on preliminary identification of NPS interest areas. [7] Stenmark arrived in Washington on January 2, met with Swem the next morning, and began work that day. [8] Swem gave him considerable flexibility in identifying interest areas and the acreages necessary. In fact, the only restrictions under which Stenmark worked were the 80,000,000-acre limit for d-2 withdrawals, pending state selections, and presence of existing federal reserves. [8] The presence of the Naval Petroleum Reserve on the North Slope, for example, prevented extending the northern boundary of the Gates of the Arctic interest area as far north as Stenmark would have liked, and prevented the Service from identifying other areas of interest on the Arctic Slope and Eastern Brooks Range. [10] Stenmark attempted to apply the principles embodied in the recently developed National Park System Plan to Alaska, and delineate interest areas according to the themes outlined in that document. Along with the existing areas, the lands initially identified would form a system of national parks and monuments in Alaska that would include a broad spectrum of scenic, scientific, cultural, and recreational values. [11] By January 4 Stenmark had completed initial identification of NPS interest areas, and his list was being reviewed by officials in the Washington office. Included among twelve natural and ten historical and archeological areas initially identified were a number that had long been considered as having National Park System potential. Other areas included one of the largest explosive craters in the world (Aniakchak), an area that included one of the most remarkable examples of arctic sand dunes along with important archeological sites (Great Kobuk Sand Dunes-Onion Portage), and an area representative of the highlands of central Alaska (Tanana Hills): Natural Areas

Historical and Archeological Areas

Prior to passage of ANCSA the Bureau of Sports Fisheries and Wildlife had identified twenty-nine areas in Alaska as having nationally significant fish and/or wildlife values. [13] Between December 22 and January 7, that agency refined its list to twenty-two areas totaling 54,190,000 acres. Included in the 106,391,000 acres the two agencies identified by January 7 were 5,717,000 acres of overlapping interest lands on the Seward Peninsula, Bristol Bay, Aniakchak Crater, Bear Lake, and Copper River-Bremner River. Although the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation was not involved at this time, the NPS and BSF&W proposed withdrawing 10,000,000 acres for study for possible inclusion in the Wild and Scenic Rivers System. [14] Between January 7, when the two agencies first presented their proposals to Assistant Secretary Reed, and March 15 the agencies themselves and departmental representatives reviewed and refined the proposals. On January 11 Reed forwarded a revised version to Undersecretary William Pecora. [15] On February 1 the agencies presented their recommendations to the department's Alaska Land Selection Task Force to Coordinate Federal Land Selections in Alaska, a committee comprised of assistant secretaries, solicitor, and legislative counsel. [16] On February 10 the agencies made their initial presentation to Secretary Morton. In the next several weeks the proposals were revised, option papers prepared, and on March 2 Assistant Secretary Reed made his final recommendations to the Secretary. [17] Additionally, agency and departmental leaders heard from Native leaders, state of Alaska officials, conservationists, and other federal agencies with an interest in Alaska lands—Forest Service, U.S. Geological Survey, Bureau of Mines, and Bureau of Indian Affairs. [18] The comments of the various groups and agencies did have an important effect on the shape of the preliminary 17(d)(2) withdrawals in March. After meeting with conservationists on February 28, for example, both the NPS and BSF&W added the Noatak, the largest complete river system unaltered by man in the United States, to their lists of interest areas. [19] Based upon input from other agencies, moreover, potential mineral lands east of Bornite on the south slope of the Brooks Range, small areas on the south side of Mount McKinley, and certain lands in the Wrangell Mountains region would not be included in the preliminary 17(d)(2) withdrawals. [20] In the final analysis, the preliminary d-2 withdrawals made in March 1972 would be the product of considerable negotiation and compromise. Pressures outside the Interior Department, not simply the assessment of resources values by agency professionals, determined the shape of those withdrawals. Section 17(d)(2) of ANCSA allowed nine months for identification of lands to be withdrawn for study as potential additions to one of the four conservation systems. Because of uncertainty as to the effect of the expiration of the ninety-day freeze mandated by section 17(d)(1), Interior Department officials assumed almost from the beginning that a preliminary withdrawal of d-2 lands would be made before that time. Secretary Morton agreed early on to this presumption. [21] Just as early, some in the Department began to consider the possibility of withdrawing additional lands under Section 17(d)(1) at the same time. [22] The idea proved appealing, despite some suspicion as to the motives behind the suggestion. Placing d-2 lands under d-1 protection would, it was believed, provide additional protection should the five-year time limit for congressional action expire. [23] It would additionally, provide for a wider final selection than otherwise possible, and the withdrawal of d-1 lands would provide a buffer around d-2 lands, allowing for a broader, eco-system approach to planning. [24] For the Park Service, which was just beginning to assess major problems faced at Everglades and Redwoods national parks, the last argument proved especially compelling. [25] The Park Service, along with the Bureau of Sports Fisheries and Wildlife proved the strongest supporters of withdrawing additional lands in March. On January 11 Congressmen John Saylor and Morris Udall seconded the arguments of those who argued for a larger withdrawal in March. Forwarding a most liberal interpretation of the relevant provisions, the two congressmen argued that such an action was certainly within the legislative intent. [26] On February 3, 1972, Assistant Secretary Reed made his preliminary recommendations for a total withdrawal of 135,000,000 acres. One month later, on March 2, he made his final recommendation for a withdrawal of approximately 80,000,000 million acres under section 17(d)(2) that would be incorporated in a larger withdrawal of 148,000,000 acres under section 17(d)(1). [27] Reed recommended that 38,865,000 acres of d-2 land be withdrawn as potential national park areas The BSF&W would have been alloted 41,026,000 acres, with 4,000,000 more for Wild and Scenic Rivers. The total recommended d-1 withdrawal would have included 61,165,000 acres for parks, 100,170,000 for refuges and 4,000,000 acres for wild and scenic rivers. [28] Secretary Reed recommended, additionally, a 17(d)(1) withdrawal for all existing refuges and for refuge replacement for lands selected by Native corporations within refuges. Finally, he recommended the withdrawal of Mount McKinley National Park and Glacier Bay National Monument from operation of the mining laws. Secretary Morton accepted Secretary Reed's recommendation, although not the total d-1 acreage proposed. On March 9, 1972, he withdrew approximately 80,000,000 acres of land under authority of 17(d)(2) and approximately 47,100,000 more acres under 17(d)(1). [29] Six days later, on March 15, Secretary Morton, saying that he intended "to move as rapidly as possible in implementing the applicable laws, while preserving good land use practices and observing the rights of everyone concerned," announced that he had signed a series of public land orders that involved some 273,000,000 acres of the public domain in Alaska. He modified, slightly, his March 9 land order in again withdrawing approximately 80,000,000 acres for possible inclusion in the conservation systems. In addition he set aside some 45,000,000 acres of d-1 lands for study and classification, made 35,000,000 acres available for state selection and 40,000,000 more for Native selection, and set aside 3,000,000 acres for "in lieu" replacement of federal wildlife refuge lands chosen by Natives, and as additional lands for transportation and utility corridors. [30]

National Park Service officials were not altogether happy with Secretary Morton's withdrawals. George Hartzog, who believed the purpose of the 17(d)(2) provision was primarily to provide for additions to the National Park System, thought that the results were a "complete disaster." [31] To meet the 80,000,000-acre limit, large areas in Gates of the Arctic, and Wrangell Mountains, as well as the entire Kenai Fjords interest area had been deleted from the NPS List, although the latter was included under BSF&W acreage. [32] Nevertheless, the March withdrawals did represent a considerable proportion of what the Service had indicated it wanted earlier:

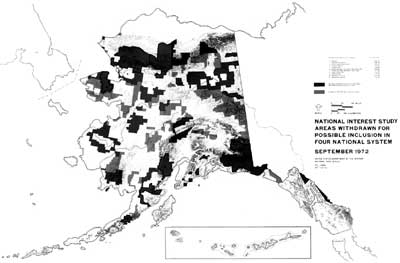

During the coming summer the Bureau of Sports Fisheries and Wildlife would study twelve areas totalling 49,000,000 acres, with some 12,000,000 acres overlapping NPS interest areas. The Bureau of Outdoor Recreation studied twenty-one rivers, totaling 5,000,000 acres. Three and a half million acres of these overlapped d-2 lands studied by other agencies. The remaining rivers were d-2 river corridors surrounded, primarily, by d-1 lands. [34] Conservationists, who had invested some $30,000 in newspaper advertisements prior to the March withdrawals, were, according to one source, "generally well pleased". with the Secretary's actions. Alaskans, on the other hand, reacted strongly to the withdrawals. The Anchorage Daily Times conjured up the image of dark deeds by repeating the centuries-old warning—"Beware of the Ides of March." Congressman Nick Begich, who had played so critical a role in the passage of ANCSA in 1971, called it a "massive land grab," while Alaska Attorney General John Havelock referred to a "sellout of the people in Alaska," and threatened to sue. Senator Ted Stevens, on the other hand, took a more concilatory stance, and generally supported the Secretary, although he disagreed with the action in some regards. [35] On January 21 the state had filed for selection of a total of 77,000,000 acres in anticipation of Secretary Morton's March withdrawals, an amount that would have substantially completed its statehood entitlement. Although Secretary Morton made 35,000,000 acres available for immediate state selection on March 15, some 42,000,000 acres of the January 21 selections remained in conflict with the March withdrawals. [36] On April 10, 1972, the state made good on its threats to sue over the March withdrawals. Claiming that Secretary Morton's actions were "arbitrary, capricious, and an abuse of discretion," the state asked the court to set aside the March withdrawals and reaffirm its January selections. [37] B. Identification of Study Areas, March-September 1972 The March 17(d)(2) withdrawals were, as indicated, only preliminary. Final withdrawal of study areas would come the following September, after an evaluation of resource values of the areas. In early January, while still involved in identification of interest areas, the Service had begun defining study techniques, developing cost estimates, and identifying possible participants for the up-coming studies. [38] By late January Director Hartzog had decided that the ANCSA implementation effort would be supervised directly by the Washington office, and on February 2, he chose Ted Swem to direct the project. [39] As defined in an April 26 "Roles and Functions" statement, the NPS Alaska effort was an agency-wide one. Swem, who reported to the director, exercised direct control over the Alaska effort, assumed responsibility for developing programs, staffing and funding requirements, and represented the Service in all intra-departmental affairs. In the field, an Alaska Task Force that reported directly to Swem while retaining a functional relationship with the Pacific Northwest Regional Office was responsible for carrying out all studies and planning activity. The Alaska Field Office, which reported to the Pacific Northwest Regional Director in Seattle, provided logistical support—personnel services, finance, and procurement. The regional office retained control of on-going operations in Alaska, while providing support services for the Alaska Task Force, and was responsible for collection of data relating to on-going park operations. The Denver Service Center would be asked, when necessary, to lend its expertise in such things as collection of land acquisition data, cost estimates of development, and the like. [40] This organization was designed to provide greater flexibility for the Alaska effort than might have been the case otherwise. It facilitated communication between the Washington office and the Alaska Task Force, giving people on the ground in Alaska a greater voice in decisions. Because the ANCSA implementation effort involved several federal agencies, retaining direct control in Washington would allow for greater coordination between agencies than was normally the case. At the same time, it did limit the role of the regional director in decision-making that directly affected his region, although he was to be kept informed of all activities of the Task Force. [41] On paper the functions of the Alaska Task Force and Alaska Field Office were different; in reality they often overlapped. It was an organization almost certain to create tension within the Service despite efforts to ameliorate them. [42] Other federal agencies prepared, as well, for the upcoming field season. Both the Forest Service and Bureau of Outdoor Recreation established special offices in Anchorage to conduct studies. The BSF&W, on the other hand, utilized its existing area office in Anchorage, sending additional staff to Alaska on detail when necessary. [43] At the departmental level the study efforts of the several agencies would be coordinated by a group headed by Frank A. Bracken, legislative counsel. [44] Swem chose Albert G. Henson, a NPS planner with wide experience in park management and new area planning to supervise the Alaska Task Force. The NPS Task Force consisted of a small core staff of five permanently assigned to Anchorage, with an additional thirty-three people detailed to Alaska for periods ranging from four to six months during 1972 and 1973. [45] The group consisted of four hand-picked, multi-disciplinary teams (each comprised of a team captain, ecologist, landscape architect, and interpretive planner) assigned to evaluate from three to four areas in a given region. [46] Additionally, a fifth team, headed by Zorro Bradley, a NPS anthropologist who also directed the Service's newly-created Cooperative Park Studies Unit at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks, studied historical and archeological areas and provided cultural resource assistance to all study teams. [47] Initial NPS studies concentrated on evaluating the park values of areas withdrawn under 17(d)(2) and 17(d)(1) to determine what lands should be included in the final 17(d)(2) withdrawals to be made by September 17, 1972. [48] The basic concern in this phase (June-September 1972), which involved an analysis of both d-2 and d-1 lands, was insuring, in so far as possible, that the recommendations to the Secretary of the Interior for final withdrawal of study areas would include the very best possible lands available. The Park Service, and its approach was shared by the BOR and somewhat reluctantly by the BSF&W, studiously concentrated on resources and avoided making recommendations regarding future management of areas. They did of course, include general recommendations regarding which agency should manage the area, but made no effort to resolve overlapping interests. [49] Following the completion of its analysis of the March withdrawal boundaries, the Task Force would undertake a regional or "eco-systems" approach to planning by studying the d-2 lands and adjacent areas to determine what, if any, land use controls should be imposed there to protect the d-2 withdrawal lands. They would initiate more detailed studies of the withdrawal areas necessary to prepare conceptual master plans, legislative support data, and environmental impact statements, all required for any legislative proposal. These studies, which were often made in concert with planning teams from other agencies and groups, would result in detailed knowledge about the areas that would be also important for future management purposes. It would result in a major addition to the existing body of knowledge about Alaska. Recommendations regarding the March withdrawals were due in the Department of the Interior by July 20 for review by the assistant secretaries as well as Frank Bracken's group. Presentation to Secretary Morton was scheduled for August 10. [50] This meant that each of the "four systems" agencies would have only a matter of weeks (until July 14, in the case of the NPS) to analyze the March withdrawal areas, prepare justifications for any changes, and make recommendations to the Secretary for the final withdrawals. [51] The National Park Service's Alaska Task Force participants arrived in Anchorage for orientation meetings on June 5-7. [52] By June 9, two teams were in the field, while the other teams worked in Anchorage, reviewing existing literature and maps. The next week, they alternated. [53] Given the limited time frame, it is obvious that on-site analysis could not be much more than cursory and that the recommendations due in July were based to a large extent on information gathered from previous studies. After weeks of virtually around the clock effort the Service recommended that Secretary Morton withdraw for study for potential additions to the National Park System eleven areas totaling 48,945,800 acres:

The Service noted, additionally, that large areas of the state should be studied to determine the extent of archeological, historical, and paleontological resources. It recommended that some means of safeguarding those resources be undertaken, either by extending to them the protection of the federal or state antiquities act, or by encouraging the Native associations to protect them along the lines adopted by other Native groups such as the Navajo tribe of Arizona and New Mexico. [54] Among the major changes recommended were the transfer of 4,368,000 acres from d-1 to d-2 status in the eastern Wrangell mountains, and deletion of Mt. Veniaminof, Nogabahara Sand Dunes, and Chukchi withdrawal areas. In the Noatak, recommended deletions of 388,900 acres in Kikmikso Mountain and the south Waring Mountains and along the Redstone Mountains were more than balanced by the recommended addition of 411,800 acres from open lands in the DeLong Mountains and Kotlik Lagoons. The latter, which included lands of potential archeological values along the coast, would become an important part of the Cape Krusenstern proposal when that area was separated from the Noatak. [55] The NPS Alaska Task Force recommended, additionally, that three units totalling 95,400 acres of the 139,600-acre withdrawal in the Kenai Fjords area be included as an NPS study area. Kenai Fjords had been included in the Service's interest areas earlier, but had been dropped in an effort to reach the 80,000,000-acre d-2 limitation. It was included in the March d-2 withdrawals as part of the BSF&W's Aialik withdrawal area. [56] The Task Force recommended that, whenever possible, Secretary Morton include in his September withdrawals, boundaries "which encompass complete watersheds, sufficient intact habitats, units of geological importance." [57] Because the study teams were unable to make more than cursory fly-over inspections of the areas at this time, mistakes understandably were made. At Gates of the Arctic, for example, the study team failed to include the Upper Ambler, Shungnak, and Kogoluktuk rivers on the western part of the proposal. [58] Nevertheless, along with the areas recommended by other federal agencies and existing park areas, the eleven NPS areas recommended for final d-2 withdrawals would, according to Francis S.L. Williamson, "make available in perpetuity to the American people [an] adequate representation of the magnificence, grandeur and biological uniqueness of Alaska." The recreational and esthetic values of the total resource, concluded Williamson, "are boundless and collectively represent a broad cross section of all those features of our natural heritage that the NPS was established to provide." [59] Additionally, the Task Force recommended joint studies with the state of Alaska and Native groups for future land use of certain lands adjoining the proposed d-2 withdrawals. These areas—the nine townships of pending state selections that included portions of the John River Valley and Wild Lake immediately south of the Gates of the Arctic withdrawal area, for example—were lands whose use would have a significant impact on the future parklands. Elsewhere, the Service recommended certain land use controls for d-1 lands adjoining the d-2 withdrawals. [60] These recommendations were the first hint of a concept that would be amplified, later, as areas of ecological concern. As was the case with the March withdrawals, Secretary Morton's final 17(d)(2) withdrawal would not be based solely on resource values as defined by bureau experts, but, rather, would be the result of a careful weighing of competing interests. As the Service's proposals moved through the various levels of the department, the Secretary heard from other Interior agencies—the USGS and BLM presented reports, for example. On August 4 Dr. Edgar Wayburn of the Sierra Club wrote Secretary Morton, offering suggestions regarding the approach he might take, and recommended the withdrawal of thirteen areas totalling some 84,000,000 acres. [61] By early August, too, the Forest Service, having completed a review of 127,000,000 acres, presented its recommendations to Secretary Morton. Commenting on the proposals of the Interior Department agencies, Forest Service officials called for an alternative "balanced system" that would provide for a "mixture of multiple use lands as well as lands of high scenic and scientific value and units of international importance to wildlife." A balanced system, agency officials concluded, would include 32,400,000 acres for potential units of the National Park System, 32,300,000 acres for refuges, 7,000,000 for wild and scenic rivers, and 41,700,000 acres for national forests, a considerable portion of which would be in interior Alaska. Subtracting 35,700,000 acres of overlaps (19,400,000 acres of proposed forest land conflicted with NPS proposals), the total acreage in the Forest Service package was 80,000,000 acres. [62] By August 16, following briefings by Native groups as well as departmental review, the combined study area acreages stood at 75,940,000 acres. NPS areas totalled 41,599,140, BSF&W's were 42,641,833, with 1,000,000 more for wild and scenic rivers and 1,500,000 for national forests. The figure included overlapping land amounting to 11,620,340 acres. [63] According to Secretary Morton, however, the Joint Federal-State Land Use Planning Commission provided the most influential advice in the decision-making process leading to the final 17(d)(2) withdrawals on September 13. [64] The commission itself did not meet until July 31—Secretary Morton had not announced his appointees until July 14. [65] By April, however, it had been decided that the Northern Alaska Planning Team, an interagency, multi-disciplinary task force of twenty-five specialists from various state and federal agencies, would be assigned to the commission as its resource planning team. [66] Throughout the summer, the resource planning team studied the March withdrawals and conflicting claims by state and Native groups to make recommendations to the full commission. On August 9-11 the commission heard from representatives of the federal agencies involved in d-2 implementation, as well as state, Natives, and Alaska conservationists. On August 16 four members of the commission met with Secretary Morton in Washington, D.C. to present its recommendations. [67] The make-up of the commission, both as mandated by ANCSA and in appointees themselves, seemed to promise a balanced approach intended by the legislation. As constituted the commission represented a cross-section of the various interest groups involved—Celia Hunter, a long-time Alaskan conservationist and Charles Herbert, a strong supporter of Alaska mining interests were on the panel, for example. [68] The commission had the responsibility of balancing all competing interests. When its recommendations were made public, however, it seemed to reflect, from the perspective of NPS planners at least, a shift toward multiple-use and joint federal-state management from dominant use as represented in the National Park System. [69] The commission made no specific recommendations regarding management or boundaries of areas. They had examined areas of state-federal conflict, however, and made specific recommendations on thirteen. In addition, they recommended several alternative policy actions. Secretary Morton could shift the entire 80,000,000 acres of d-2 lands to d-1, with some restrictions on taking of minerals, or he could transfer any portion of the d-2 lands in conflict with state or Native designations (15,000,000 acres) to d-1 status. [70] Overall, the effect on the Service's d-2 withdrawal recommendations was not as great as many feared it would be. However, the Commission's recommendations in at least three areas—Gates of the Arctic, Mount McKinley and Lake Clark—would have an impact when they were included in an out-of-court agreement that resolved the lawsuit filed by the state of Alaska in April 1972 over conflict between state selections and Secretary Morton's March withdrawals. In a September 2 agreement with Secretary Morton the state agreed to drop its lawsuit and its claim to 42,000,000 acres of pre-selected land in return for immediate selection rights to lands on the south slope of the Brooks Range, south of Mount McKinley National Park, and in the central part of the Brooks Range. An additional clause that would bulk larger later, opened lands along Antler Bay, Cape Kumlik, and Aniakchak Bay in the Park Service's Aniakchak interest area to sport hunting. [71] On September 13, 1972, Secretary Morton announced the final 17(d)(2) withdrawal of twenty-two areas totalling 79,300,000 acres of land in Alaska for study for possible addition to the National Park, Forest, Wildlife Refuge, and Wild and Scenic Rivers systems. [72] Actually, insofar as the Park Service was concerned, the September 2 agreement had predetermined the nature of the September withdrawals. There were no surprises in Secretary Morton's withdrawals.

In the decision-making process that led to the September withdrawals, the Park Service lost 600,000 acres of critical caribou range in the recommended additions to Mount McKinley National Park, and important access routes into Mount McKinley (Chelatna Lake/Sunflower Basin) and Gates of the Arctic (Alatna and John Rivers). Clark proposal was severely compromised, and the Tanana hills portion of the Tanana Hills-Yukon River area had been eliminated. Much of the proposed transfer of d-1 lands to d-2 status in Wrangell-St. Elias had been deleted. [73] NPS Alaska Task Force planners watched apprehensively the process leading to the September withdrawals, writing in August, for example, "we got all the rock and ice we asked for" at Mount McKinley, or somewhat sarcastically observing, as Paul Fritz did, that Wrangell-Saint Elias be named "The Great Glacier National Park." [74] Despite their concerns, the Park Service received most of the land Alaska task force planners believed necessary for study as potential parklands:

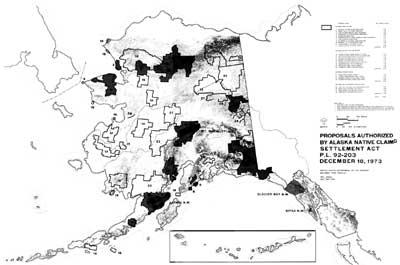

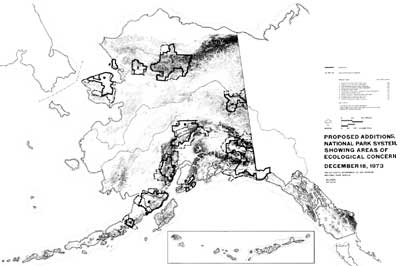

C. Preparation of Legislative Recommendations In preparation for the March and September withdrawals, the Park Service had concentrated its efforts on refining proposed withdrawal areas without determination of resource uses or future management. Even as the process of determining the September withdrawals was underway the Service had begun to shift its focus to more detailed studies of the areas. Before December 18, 1973—the date mandated for submission of legislative recommendations—decisions on final boundaries would have to be made. Conceptual master plans that would delineate management proposals for the proposed areas, environmental impact statements, and detailed legislative support data for each area—information required for any piece of legislation—would have to be completed. [76] In addition the Park Service would prepare individual bills for the areas should those be necessary. [77] Because congressional committees traditionally required the key witnesses be intimately familiar with the areas, intensive on-the-ground inspection of each area, which had not been possible in the early phases, would be undertaken. [78] At the same time, the Service would continue to expand and improve the relationships with the Native community. [79] In that regard, too, the Service would have to address the question of dual withdrawals—lands withdrawn both as d-2 land and for Native corporations. Efforts to resolve the dual withdrawals, which included lands in Lake Clark, Aniakchak, Chukchi-Imuruk, and Gates of the Arctic, would continue into the post-ANILCA period. [80] No effort had been made, additionally, to resolve the question of overlapping interest areas in preparing for the September withdrawals. Decisions regarding management of such areas as the Upper Yukon, Copper River, Chukchi-Imuruk, and Noatak, all areas in which both the NPS and BSF&W had expressed an interest, would have to be made before the legislation went forward to Congress. [81] As well, the overlapping interests between Interior Department agencies and Forest Service, which amounted to 31,000,000 acres, would have to be addressed. By April 1973 the Bureau of Land Management had complicated the process when it introduced its own proposal for management of large areas. The Bureau's "fifth system" concept was a "multiple use planning effort with emphasis on Chitina Valley, Iliamna, White Mountains, Fortymile and Noatak Planning Units." [82] All agencies involved would have to deal with a variety of complicated policy issues in preparing legislative recommendations—subsistence uses, areas of ecological concern, coastal and navigable waters, mining and mineral leasing, and wilderness. [83] The Park Service and BSF&W, as indicated, had cooperated in their Alaska efforts from the beginning. In early January 1973 the two agencies had begun to work out overlaps at the Alaska level. [84] By early January, Assistant Secretary Reed had decided that these questions would be best dealt with by some central group that would coordinate the efforts of the several Interior Department agencies involved. [85] At the same time, such an organization it was believed, would overcome any opposition to the Alaska effort within the individual agencies, and would resolve any conflicts between agencies to present a solid front to the rest of the department. On February 15, 1973, Secretary Reed announced the formation of an Alaska Planning Group, made up of representatives from the NPS, BSF&W, and BOR. The group would be chaired by Theodor Swem, who would also serve as representative of the National Park Service. [86] The Alaska Planning Group would coordinate the efforts of Interior Department agencies in implementation of ANCSA. The APG was responsible for the completion of all requirements necessary for submission of legislative proposals, and all required support documentation for proposed additions to the four systems that must be submitted by December 18, 1973. It would work directly with the Department's Alaska Task Force, a committee made up of deputy assistant secretaries, assistant secretary of agriculture, and chaired by Ken Brown, departmental legislative counsel. This Alaska Task Force was had overall responsibility for coordinating the Interior Department's effort in implementing ANCSA. [87] Work on conceptual master plans and environmental impact statements and continued boundary refinements began as soon as the Park Service's Alaska Task Force completed the recommendations to Secretary Morton for the September 1972 d-2 withdrawals. In the shortened 1972 field season NPS study teams fanned out across Alaska to collect the detailed information necessary for preparation of those documents. Often made in conjunction with people from other federal agencies, state, Joint Federal-State Land Use Planning Commission, and members of conservation organizations, these inspection trips served, as well, to obtain the "I've been there" experience traditionally required of key witnesses by congressional committees. [88] As the study teams undertook more detailed analysis of the study areas they realized, that despite the previous studies, the level of available knowledge was often inadequate for their purposes. By way of example, ATF planners recognized from the very beginning that subsistence would be significant question throughout the process. Yet, no hard data on the extent or location of that activity existed. Equally important, one of the charges made in opposition to withdrawal of such large areas was that it would "lock-up" substantial mineral wealth. Yet neither the Service nor those who opposed their efforts possessed adequate documentation to support their arguments. In 1972 the Task Force had contracted for an assessment of the areas included in the July recommendations and for an annotated bibliography of relevant topics. [89] In 1973, the Service initiated a broad research program that would result in a long list of original studies when it contracted for a botany study of Gates of the Arctic, and multi-disciplinary studies at Noatak and Chukchi-Imuruk. [90] On January 18, 1973, Al Henson submitted a revised financial plan that included $450,000 for research. [91] Over the next several years the variety of research reports produced by or for the Park Service would give park planners as well as future managers an intimate knowledge of the Alaskan areas. The program, which was probably unique in the Service's history, produced a number of ground-breaking studies and resulted in a significant contribution to knowledge about Alaska. By 1978 some 176 studies had been completed, and another 61 were underway. The Service estimated that by that date 400 man-years of research (including pre-ANCSA NPS studies) had been accomplished. [92] As the process of preparing master plans and environmental impact statements went on, moreover, Alaska Task Force study teams became increasingly aware that many of the concepts that guided NPS planners elsewhere were not relevant when planning in Alaska. Limited time, a concern that the Service would be accused of attempting to close too much land, and an inadequate data base limited their options, however. As a result, management proposals for the proposed Alaskan parklands represented a sometimes curious mixture of creative management concepts and 'state of the art' park planning with its emphasis on visitor use and development. At Gates of the Arctic, for example, NPS planners proposed a two-unit National Wilderness Park. In the middle, located on Native lands would be a 2,100,000-acre Nunamiut-Koyukuk National Wildlands, to be managed cooperatively by the Park Service and Arctic Slope Regional Corporation, which had selected the land. A permit-reservation system, upon which the whole concept of a wilderness park was predicated, would control the number of people allowed in the area. The Noatak would be a jointly managed (NPS and BSF&W) National Ecological Reserve, set aside to protect "in perpetuity two major arctic valley ecosystems, now virtually unaffected by civilization, for their scientific and educational values." A most creative concept forwarded was a proposed Noatak Conservancy—a board of eminent scientists, educators, local residents, and conservationists—who would advise on all management decisions, policies, and programs, and review all environmental impact statements for area projects. [93] Elsewhere, task force planners sometimes emphasized visitor use on a scale that today seems inappropriate for the place. At Yukon-Charley National Rivers, which was to be managed as a recreation area, the planners proposed a visitor complex at Woodchopper/Coal Creek that included a ranger station, visitor accommodations, air and boat charters, canoe rental facilities, horse trips, interpretive and research facilities. Other visitor facilities would be located, as well, on the Charley, Kandik, and Nation rivers, and at Johnson's Gorge. At the proposed Aniakchak Caldera National Monument, an isolated area on the Alaskan Peninsula, the Service recommended a development site at Meshik Lake and two "other development sites" within the crater itself. [94] Although hampered by a lack of knowledge in some areas as well as an unrealistic deadline imposed by ANCSA, Alaska Task Force planners nonetheless completed the major portion of the required documents as scheduled. By early January the first of the "Description of Environment" sections of the proposed environmental impact statements were out for review and on January 26 study packages for Gates of the Arctic and Mount McKinley were scheduled for completion. By May 15 the last of the study packages—Lake Clark and Kenai Fjords—had been submitted for review. [95] The Alaska Task Force was, additionally, well on the way to completion of the environmental impact statements for each of its proposals as required by the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969. However, questions regarding the format and substance of those documents, as well as those being prepared by other agencies, existed. [96] Past difficulties that all agencies had experienced, as well as the need for consistency in policy statements and graphics, led to the decision that a single set of documents would be prepared in Washington under the immediate supervision of the Alaska Planning Group. Accordingly, in late summer 1973 the APG established a multi-agency task force, coordinated by Bill Reffalt, a biologist assigned to the BSF&W's ANCSA staff, to prepare the necessary documents. The task force, which included representatives of five agencies and at times involved as many as sixty writers, typists, graphic specialists, and consultants. By December 18, 1973, the task force had completed draft environmental impact statements for each of the twenty-eight areas included in Secretary Morton's legislative proposals. Final statements revised to reflect comments by a wide variety of agencies, organizations, and individuals, would be completed in December 1974. [97] On April 25, 1973, the Alaska Planning Group met for the first time to consider individual proposals when members discussed Mount McKinley, Katmai, Yukon Flats, Coastal Refuges and Fortymile. [98] Following long, and sometimes acrimonious debate, the Alaska Planning Group had substantially resolved the issues by June 16, the date the combined proposals went forward to Assistant Secretary Reed. Resolution of the question of overlapping interest areas (NPS and BSF&W) had actually begun earlier at the local level. As early as December 1972 the NPS Alaska Task Force considered joint management of the Noatak as a solution there, and had so recommended. [99] At Chukchi-Imuruk, on the other hand, the NPS study team decided that, despite the obvious wildlife values, the area most properly belonged in the National Park System, and submitted the issue to the APG for resolution. [100] Accepting the recommendation of the NPS Alaska Task Force, the APG endorsed the concept of joint management at Noatak, as well as for the two southern units of the proposed Harding Icefields - Kenai Fjords National Park. They overrode the recommendations of the NPS Alaska Task Force by proposing joint management at Chukchi-Imuruk. The group decided that in Kobuk Valley, the Upper Yukon and Copper River areas, park values outweighed wildlife values and reaffirmed NPS proposals there. [101] Following resolution of overlapping interest areas, the APG, as well as individual d-2 agencies, Bureau of Mines and USGS, made presentations to the assistant secretaries in late June and early July. The Alaska Planning Group presented a package for departmental review that included 85,390,360 acres. Included were 32,242,000 acres of refuges, 4,067,360 acres for Wild and Scenic Rivers, and 49,081,000 acres in proposed National Park Service areas:

Differences existed, even within the Interior Department, as to whether the 80,000,000-acre limit in Section 17(d)(2) referred only to the September 1972 study area withdrawals, or whether the legislative intent was to limit as well the total acreage in the interior secretary's December 1973 recommendations to Congress. Secretary Morton, and he was supported in his view by Representatives John Saylor and Morris Udall, clearly believed the former was true. [103] In an effort to avoid potential difficulties, however, Secretary Morton decided that the Interior Department's legislative proposal would be generally within the 80,000,000-acre range. [104] The process of review following preparation of the APG's June proposals was similar to that prior to the March and September withdrawals. Political pressures, the Secretary's decision to restrict the total acreage, and his own conviction that the only potentially successful proposal would be one that achieved a balance between multiple and dominant use molded the December 1973 recommendations. On August 8, for example, the Federal-State Land Use Planning Commission, which had held a series of hearings in thirty Alaskan communities and four more "outside" in May and June, presented its preliminary recommendations. Identifying "primary values" in twenty-six d-2 areas, the commission recommended nearly 18,000,000 acres as waterfowl, fish and wildlife habitat; and 22,469,000 more for a combination of recreational uses, and scenic and natural features. Some 61,000,000 acres, much of it overlapping other areas, were identified for mineral exploration and extraction with varying degrees of regulation. Another 37,000,000 acres were proposed for a variety of uses. Finally, the commission recommended that all d-2 lands remain open for fishing and hunting, except for 3,000,000 acres in the central Brooks Range, Wrangell-Chugach, and Mount McKinley areas. [105] The most important single factor that determined the shape of the December legislative proposals, however, was concessions won by Agriculture Secretary Earl Butz on behalf of the Forest Service. In July the Forest Service published its final recommendations, calling for the establishment of seven national forests, and five separate additions to Chugach and Tongass national forests. [106] The proposal, which totaled nearly 42,000,000 acres, was similar to that presented to Secretary Morton the previous year, a package he had then criticized as "an effort to get into the Bureau of Land Management business." [107] Morton had substantially ignored the Forest Service proposal at that time, and Park Service employees hoped that he would do so again. In 1973, however, he was unable or unwilling to do so again. Beginning in early August and continuing into October officials in the Interior Department negotiated with their counterparts in the Department of Agriculture. On August 9 the Forest Service presented its revised "Suggested Balanced System," a 77,300,000-acre proposal that included 31,800,000 acres in forests, 24,000,000 in parks, 20,500,000 in refuges, and 1,000,000 acres of wild and scenic rivers. [108] Following a series of offers, counter-offers, and face-to-face meetings, Secretaries Morton and Butz agreed to a compromise package that included 18,800,000 acres of new national forests—Porcupine (5,500,000), Kuskokwim (7,300,000), Wrangell Mountains (5,500,000), and a 500,000-acre addition to existing forests. [109] There are differences of opinion as to the reason Secretary Morton agreed to the concession, one that certainly outraged conservationists and demoralized agency and departmental staffs. Robert Cahn suggests that Butz used his position as one of President Nixon's four "superlevel cabinet counselors" to force Morton to agree. Curtis Bohlen, who was deputy Assistant Secretary of the Interior at the time, believes that Morton's determination to develop a bill that would appeal to the broadest possible constituency was a more important factor. [110] One area the NPS lost in the negotiations—the Noatak—was most certainly a part of an effort to increase the acreage of multiple use areas. The Noatak had been proposed in June 1973 as the "National Ecological Reserve", managed jointly by the NPS and BSF&W. By September 22, when the proposal was prepared for Secretary Butz's consideration, the Noatak was listed under "Multiple Use Management" areas with the NPS, BSF&W, and BLM as management agencies. On October 16 Swem learned that the department had proposed a Noatak National Ecological Range, administered by the BSF&W and BLM. Swem appealed the decision to the departmental Alaska Task Force, but to no avail. [111] The Morton-Butz compromise did much to shape the final product. It was not, however, the last change made in the proposals. In fact, resulting from continuing discussions within the department as well as reviews by other agencies, changes were made in the proposal to the very day the legislative recommendations went to Congress. [112] On October 31, for example, a disagreement arose in the Alaska Planning Group regarding the location of the boundary between Katmai National Monument and Iliamna National Ecological Range. [113] Following OMB criticism of new unit classifications in the proposals, Chukchi-Imuruk National Wildlands, a unit included in both the National Park and National Wildlife Refuge systems became the proposed Chukchi-Imuruk National Reserve, to be managed by the Park Service. [114] At the same time, OMB forced deletion of a provision providing for preferential hiring of Alaska Natives. In a decision which most, including Secretary Morton at his December 18 press conference, criticized, OMB forced the Department to delete the "instant wilderness" designation of Gates of the Arctic. [115] D. The Morton Proposals On December 17, 1972, Interior Secretary Morton forwarded the proposed legislation to Congress. The bill, which, he said, sought to preserve some of the most "majestic territory on earth, along with lands and rivers that support some of the most exciting fish and wildlife," was the product of considerable negotiation and compromise, and sought to strike a balance between potential resource users. If this had not been accomplished, concluded Morton, "we have erred on the side of conservation." [116] Secretary Morton proposed adding 83,470,000 acres to the National Park, Wildlife Refuge, Forest, and Wild and Scenic Rivers systems. [117] Included were additions to Mount McKinley National Park and Katmai National Monument (which would become Katmai National Park with passage of the bill), establishment of three new parks, four national monuments, one national river, and one national reserve. The total acreage recommended, which would more than double the size of the existing park system, was 32,600,000 acres:

Nine areas totalling 31,590,000 acres would be added to the National Wildlife Refuge system. The 18,800,000 acres of proposed new national forests were those agreed to by Secretaries Morton and Butz in October. Additions to the Wild and Scenic Rivers System (820,000 acres) would have included sixteen rivers within d-2 areas and four more—Beaver Creek, Fortymile, Birch Creek, and Unalakeet—outside. The bill proposed joint management for four areas. The Park Service and BSF&W would manage Chukchi-Imuruk National Reserve and the two southern units of Harding Icefield-Kenai Fjords. The BSF&W and BLM would cooperate to manage Iliamna National Resource Range and Noatak National Arctic Range. [119]

The proposal provided for continued traditional subsistence uses in all d-2 areas and withdrew all park areas except the Charley River watershed in the Yukon-Charley National Rivers from all forms of appropriation including mineral leasing laws, and provided for a three-year wilderness review. It would have allowed the Secretary of Interior to enter into cooperative agreements concerning the use of privately owned lands adjacent the park areas. These lands, known as areas of ecological concern, were not part of the system, but were critical to the ecosystem of the park. [Illustration 10]. [120]

In terms of the Park Service, the most controversial provision in the bill was that which would have allowed the continuation of sport hunting in Aniakchak, Lake Clark, Wrangell-St. Elias, Gates of the Arctic, Chukchi-Imuruk, and Yukon-Charley National Rivers. Conventional wisdom in the Service suggests that the provision for sport hunting in park areas, which was included at the insistence of the Interior Department over the opposition of the Park Service, resulted from the September 1972 agreement between the state of Alaska and Secretary Morton. [121] That agreement, however, referred only to sport hunting in selected townships of the proposed Aniakchak Caldera National Monument. Provision for sport hunting in the other areas seems to have been more a response to pressure from wildlife management and hunting groups. Secretary Morton's desire to appeal to the widest possible constituency also seems a more compelling reason, although it is likely that the agreement to allow hunting at Aniakchak did make it easier to allow it elsewhere. [122] Perhaps because Secretary Morton had tried to achieve a balance between competing interest groups, the proposal succeeded in pleasing very few. Forest Service representatives admitted that they were not completely satisfied with the way things came out. Many Alaskans, including the congressional delegation, governor, and editorial opinion in the state, opposed the proposal as one that would strangle the state's economy by "locking up" too much land in parks and refuges, rather than in multiple-use areas. In March state officials indicated that they would go to court to protest the proposals. [124] Conservationists, on the other hand, had viewed the decision-making process leading to the proposal with growing dismay, as more and more lands they believed should be preserved as parks and refuges found their way into multiple-use categories. In May the Wilderness Society had taken out a full-page newspaper advertisement to bring pressure on Secretary Morton. On November 30, the Wilderness Society, National Audubon Society, Sierra Club, and Friends of the Earth formed the Emergency Wildlife and Wilderness Coalition for Alaska, taking its campaign to the public with advertisements in major newspapers across the country in an attempt to reverse decisions already made. By November 1973 both the Sierra Club and Wilderness Society had completed draft legislation that proposed setting aside 119,600,000 acres of land in Alaska. Included were 62,000,000 acres of national parks:

For the National Park Service, the Morton proposal was a bitter-sweet one. The bill proposed to double the size of the National Park System in one fell swoop with areas of unsurpassed grandeur. [126] Yet at the same time, NPS planners were distressed over the loss of the Noatak, which Francis Williamson had called the "best all-around choice made by the Task Force" [127] The proposed 5,500,000-acre Wrangell National Forest on the flanks of Wrangell-Saint Elias National Park seemed to NPS planners to be a particularly "obscene" arrangement, leaving as it did, a park consisting primarily of "rock and ice." Equally galling to Alaska planners, was the failure to include a strong regional planning provision, something which most involved felt would be essential for the future of the Alaska parks, and loss of wilderness designation for Gates of the Arctic National Park. [128] The provision that allowed for continued sport hunting in proposed new park units proved especially disturbing, flying, as it did, in the face of a tradition of an opposition to hunting in the national parks that dated to the earliest general statement of National Park Service policy in 1918. [129] There is some evidence to suggest, it is true, that when Interior Department officials included a hunting provision to placate hunting interests, no one seriously expected that it would survive congressional scrutiny. [130] Nevertheless, the provision concerned a great many, although by no means all, NPS employees, their allies in the conservation community, and counterparts in the Canadian National Parks. [131] There is no doubt that the Morton proposal had serious shortcomings. It would have benefitted from additional study and planning. The Secretary had, of course, no choice but to submit the proposal on that date. Congress had mandated the date for submission of the proposals in ANCSA, however unrealistic that date might have been. In retrospect, it seems that, given the political considerations under which bureau and departmental officials worked, the need to listen to and balance all views, the state of the knowledge of the Alaskan areas, the too-limited time frame mandated by Congress for submission of recommendations, and uncertainty that existed regarding Native land selections, the Morton proposal went as far as was then possible. It defined areas upon which others would build. In the areas of ecological concern NPS and Department of the Interior officials had been able to make public what they considered to be ideal boundaries for the proposed park units. Later proposals would represent, in large part, extensions into those 1973 areas of ecological concern. [132] Lastly, the recommendation of 83,000,000 acres broke a psychological barrier, by making a clear statement that the 80,000,000-acre limitation of section 17(d)(2) did not bind the legislative recommendations of the Secretary of the Interior. It established, finally, a base below which any future administration would find it difficult to go. Between January 1, 1972 and December 18, 1973, the Interior Department and individual bureau staffs had expended enormous amount of time in preparation of the legislative recommendations mandated by ANCSA. [133] Compromise that was often painful to agency professionals, however, characterized the decision-making process that led to the recommendations forwarded to Congress by Secretary Morton on December 17, 1973. At each stage the various interest groups had the opportunity to argue their views, and the final product was an effort to balance their interests. Yet despite the debate that had taken place and the compromises made, it became clear almost as soon as Secretary Morton forwarded the proposal that passage of any bill that provided for additions to the four systems in Alaska would come only after a long and arduous process. On January 29 Congressman James Haley introduced the Morton proposal as H.R. 12336, and the next day Senator Henry Jackson introduced the Senate version of the bill. [134] At the same time Jackson introduced, at the behest of conservationists, a bill calling for the addition of 106,094,000 acres to the four conservation systems. [135] Over the next several months other bills had been introduced to establish a cultural park in the Brooks Range (Nunamuit National Wildland) and to increase the number of wildlife refuges in Alaska. [136] Additionally, others began to work up proposals, and members of the Alaska Congressional delegation indicated that alternative legislative proposals would be forthcoming. [137] These were only the first of a sometimes bewildering array of bills introduced over the next several years regarding the National Interest Lands in Alaska. For seven years the question would be before Congress. By the time a bill finally passed in 1980, the question had become the most thoroughly debated one of the history of conservation in the United States. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

williss/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 29-Feb-2016