|

MESA VERDE

The Archeological Survey of Wetherill Mesa Mesa Verde National Park—Colorado |

|

A PROLOGUE TO THE PROJECT (continued)

DOUGLAS OSBORNE

the project in diagram form

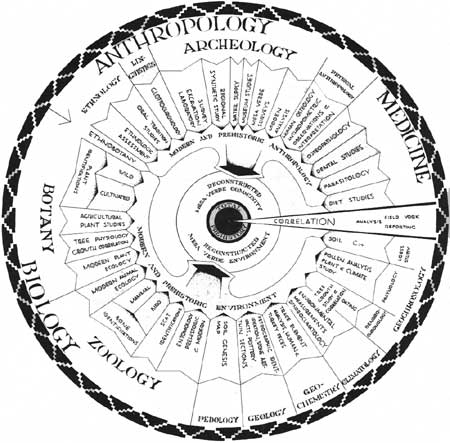

There are some 32 separate fields of study being brought to bear on problems and questions concerning the past and present environments of a small part of Mesa Verde National Park. This area is sufficiently varied so that the results will serve for the whole park.

A diagram is by far the simplest method of illustrating the size and varied complexity of interrelationships which form the project. Experimentation eliminated several approaches to the required graphic illustration. A wheel or target plan appeared to be the clearest and most true to fact.

George S. Cattanach, Jr., and Arthur H. Rohn, Jr., using a rough sketch that I prepared, made the working drawing, and George A. King did the final rendering.

The circle diagram shows the scope of the project as it stands in its fourth year. No scale is implied; the sizes of the interspoke boxes betoken no measure of scientific importance.

|

| (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The circular chart is divided into two major sections: the anthropological and medical sciences in the first, and the earth, life, and meteorological sciences in the second. The first grouping yields data and interpretation which will permit development of a reasonably clear picture of the prehistoric way of life at Mesa Verde and of the circumstances that contributed to its decline as an ancient Pueblo Indian center, the reasons for its abandonment, and something of the movements and fates of the emigrants and their descendants. The second grouping is designed to fill out knowledge of the environments of the past and present, and to provide dates for the cultural materials. Environmental change was presumably related to cultural change.

I shall discuss briefly each of the blocks in the chart starting with ethnology. It will not be possible to present findings and interpretations, even briefly. Rather I shall concentrate on the program, now well crystallized, and the reasons therefor. Many of the results achieved by 1961 were discussed in the 1961 symposium in Denver. There have been changes in emphasis since then. The project's concept is dynamic and experimental.

Anthropology. Ethnologic assessment appears in many archeological reports. In using this term I mean simply an evaluation of certain of the archeological remains in terms of the cultures of what are presumed to be their closest living cultural relatives. We shall ask ethnologists who have specialized in the Pueblo Indians to review our archeological reports, especially ground plans of the ruins, and to comment on any aspects of the non-material culture that they may discern therein, such as kinship groupings, religious practices, and others.

Groups of Rio Grande Pueblo Indians have been brought to Mesa Verde with the help of Florence Hawley Ellis of the University of New Mexico. These Pueblo men and women have examined archeological materials in the laboratory and have made valuable comments. More visits of this nature are planned. In addition, staff members make constant use of the voluminous literature on Southwestern ethnology as references.

Oral tradition studies are being carried on by Dr. Ellis. She is working with Keres-speaking Indians from Acoma, Laguna, Zia, and Santa Ana, and with the Tanoan speakers of Taos. The Keres have often been mentioned as possible descendants of the Mesa Verde peoples. The legendary history of these people is being explored in an effort to evaluate and use it in clarifying their pre-history from the point of view of origins. Most of the legends have a religious function and are not readily available. The same is true of Taos legends. Some legends are surprisingly specific and appear to correlate periods of drought and migration. Dwelling areas or sites of the past two or three centuries may correlate with phases mentioned in the myths and, at the same time, bridge to the archeological past, primarily through pottery relationships. The trail is tenuous but inviting.

A survey of the Tanoans, exclusive of Taos, was made by Kenneth and Mary Knudson of the University of Arizona. The Tanoan data were not available, and the project has therefore concentrated on the Keres and Taos alone.

Glottochronology, an anthropologically influenced approach to linguistic time depth, is being employed by James Goss, University of Chicago, who is working with local Ute groups. Nomadic incursions have often been mentioned as a factor in the abandonment of the area by the Pueblo people of Mesa Verde. The Navajo and Apache have been removed from consideration by studies which show that these people are apparently too late in the area. It is conceivable that the Utes were earlier and that glottochronology will suggest a finer Ute linguistic divergence than previously recorded which can be interpreted as a period of movement. If this falls in the 12th or 13th centuries, it will be of interest and probably of significance in Mesa Verde prehistory.

Regional syntheses are logical developments of any archeological program. They are attempts, based on the knowledge and theory of the moment, to interpret local and regional knowledge in terms of one another. Syntheses of this kind are a part of the Wetherill Mesa publication program. This work will be based primarily on published data and will be done by various members of the staff.

Water-supply studies are a part of the archeological program, but they are not a part of the federally supported program. A brief evaluative study of the best-preserved ditches, reservoirs, check dams, and terraces on Wetherill Mesa and elsewhere in the Mesa Verde area will be made. This work will be done by Arthur Rohn, who has already completed similar studies elsewhere. Richard B. Woodbury, University of Arizona, has visited the area and advised Rohn.

Both the Colorado State Museum in Denver and the University Museum in Philadelphia have large collections of artifacts taken from Mesa Verde during the last quarter of the 19th century. Although only a minor part of the artifacts in these museums can be confidently assigned to specific sites, most of them were collected by the Wetherill family and so are indubitably native to the area. The Denver collection was studied during 1962 and the Philadelphia material is now being studied. This work, which is expected to round out our understanding of the technology and material culture of the Pueblo III population, is being carried on by Carolyn M. and Douglas Osborne.

"Mesa Verde Surveys" refers to an attempt to follow the Mesa Verde cultural style as it spread and developed after the abandonment of this area. A series of archeological surveys is under way in regions to which the San Juan Mesa Verde peoples may have dispersed after they left the Four Corners area in the late 1200's or early 1300's. During the summer of 1961 a field party worked in the vicinity of Magdalena and in the Mount Taylor areas of New Mexico, collecting sherds and locating sites which may have Mesa Verde affiliations. In 1962 a detailed study was made of the black-on-white pottery recovered in 1961 and on that collected previously, under other auspices, from the region lying generally southeast of the Four Corners area. The first fieldwork was done by Emma Lou Davis of the University of California at Los Angeles and James Winkler of the University of New Mexico. Mrs. Davis is responsible for this program.

Midden analysis, as developed primarily at the University of California, Berkeley, consists of mechanical and chemical analyses of the materials that make up a prehistoric garbage dump. Richard Brooks used the mechanical method in sampling Long House, Mug House, and Step House trash. This has yielded detailed knowledge of some aspects of late occupational middens.

The work in physical anthropology consists of metric recording of human skeletal remains from archeological excavations, together with pertinent observations and interpretation. These studies follow a generally accepted pattern. It is too early yet to say whether analysis will reveal genetic traits that can be readily isolated or traced in the bones from excavations. Frederick S. Hulse, University of Arizona, is analyzing skeletal materials with the assistance (in 1962) of Charles Merbs, University of Wisconsin.

An osteopathological examination of skeletal material is a useful adjunct to physical anthropology. Ordinarily the osteopathologist has an opportunity to examine only those obviously pathological bones which are sent to him by the archeologist or by the physical anthropologist, but in this instance the entire collections are being sent to James S. Miles, orthopedic surgeon at University of Colorado Medical Center. Here they will be examined by Dr. Miles and his students. All pathologies or abnormalities will be observed, recorded, and interpreted.

The orthodontics of the Wetherill Mesa remains are being studied by E. H. Hixon, orthodontist, of the University of Oregon Dental School, Portland. This research is frankly experimental, and so its anthropological utility remains to be seen. For example, the orthodontist is still uncertain as to whether the profiles of development that are normal for children and young people among ourselves were normal among the Mongoloid Pueblo Indians of the past.

Parasitological investigations of human fecal samples taken from the cliff dwellings are being pursued by Robert Samuels of Meharry Medical College, Nashville, Tenn. Specimens examined so far indicate that the ancient Mesa Verdeans did not support a heavy endo-parasitic fauna.

Diet studies, based on the fecal remains which appear in surprising quantity in the cliff dwellings, appear to be a possibility. Amino and fatty acids in Long House feces have been identified at the Carnegie Institution of Washington by Patrick Parker and Bruno E. Sabels. The interpretation of these analyses depends on our ability, as archeologists, to relate the specimens to different periods of the occupation of Wetherill Mesa. It is known that long-range studies of this sort reveal a correlation between the amount of ingested trace elements, primarily manganese and phosphorus, found in fecal material, and large or coarse aspects of climate change. Because our studies are limited to short periods, the utility of this method for climatic interpretation over brief spans of comparative recency is not clearly known. Therefore this study also is, in part, an experimental one.

Geochronology-Pedology. The geochronological segment itself is small, but the chart divisions are misleading. The development and assessment of chronologies are also functions of a number of the other divisions.

Loess or loessic soils mantle much of the Wetherill Mesa area. Fine red dust is riding in on today's winds, apparently derived primarily from the southwest. We have an excellent column of loess in the park going through 8 to 9 feet of fine red soil to a caliche level, to residual sandstone on the bottom. Orville A. Parsons a Soil Conservation Service soil scientist assigned to the project, has studied this profile intensively. Samples have been sent to Gustaf Arrhenius at Scripps Institute of Oceanography, and a radiocarbon date on the lower caliche of not less than 35,500 years has been received from Isotopes, Inc. Other radiocarbon dates will be forthcoming. Olof Arrhenius of Grodinge, Sweden, has run chemical analyses on this and other soil profiles from Mesa Verde. The loess study cannot be expected to throw light on the aboriginal period here, but it is of interest in itself and may be important in soil genesis study.

Palynobogical work for the project is being done by William Byers of the Geochronology Laboratories, University of Arizona, under the direction of Paul S. Martin and Terah L. Smiley. James Schoenwetter worked on the pollen in 1960. Hundreds of samples have been taken from transects on the mesa top, from deposits in the ruins, and behind check dams or terraces in ravines. These are evaluated and counted in accordance with methods developed for pollen analysis of dry deposits. The results are encouraging and indicate that we shall be able to make generalizations about the flora and also identify floristic changes during the occupation and after abandonment. Such information is not only useful to archeologists but it also helps soil scientists and ecologists to, make gross-climate determinations.

The dendrochronology, dendroclimatology, tree growth, and environmental measurement studies make a tight package of multidisciplinary interdependence.

Dendrochronology is a well-known method for dating wood fragments. Wood is being dated by the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research of the University of Arizona. Although juniper wood is difficult to date, much Juniperus is yielding to modern techniques. An effort is made to date all of one season's specimens by the time the next season arrives. Over 200 dates have been established and as many more will be established before the project is completed. These form the chronological skeleton for archeological interpretation and the hard core of original fact for the climatological study. Robert F. Nichols and Thomas P. Harlan, working under Bryant Bannister, have done this dating.

Dendrochronological research has two major aspects. The first is dating of specimens from the ruins. The other aspect is somewhat more complex and goes back to some of the methods and initial theories of A. E. Douglass in the early development of dendrochronology. We have taken core samplings from trees in various environmental situations within Mesa Verde, trying to get as many of the older trees as possible. Dendrographs and dendrometers have been installed on conifers near the environmental measurement stations discussed below. In these ways we shall have: first, a long series of samples reaching back several hundred years; second, a complete record of tree growth of the present for comparison with the record of climatic and yearly variation from our weather stations; and third, the tree-ring record from excavated and surveyed sites. Anatomical studies of the growth of the trees being recorded by the dendrographs and dendrometers are going forward. This requires samplings of the xylem during the growing season, cores, and phenological observations of the trees themselves.

It should be noted that the tree-growth study has been listed a second time across the circle under "botany." The objective of the tree-growth and dendroclimatology portion of the project is to establish a basis for use of tree-rings in comparing our present-day climate with that of the past. Simply stated, the equation should read: modern tree growth is to modern environment as past tree growth is to past environments. We already have a well-documented tree-ring chronology which continues to be strengthened through current archeological excavations. By measuring present environment and tree growth and relating this to the dendrochronological series, an attempt will be made to derive an equation for estimating past climates. The significance of this program revolves around the fact that a number of representative trees adjacent to several environmental stations can be studied, thus providing a control for the variety of tree-growth situations.

The study consists of (1) measuring and evaluating current tree growth by means of 30 dendrometers, 9 dendrographs, and weekly cambial samples of the bark and outer xylem taken with a 1/4-inch leather punch; (2) making phenological observations throughout the growing season in conjunction with environmental measurements; and (3) collecting tree cores from several species for correlations of ring widths with weather records of the park, and for evaluation of the variability inherent in sampling ring series from trees in a variety of sites.

Staff members of the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, University of Arizona, under the general direction of William McGinnies, aided by the environmental measurement staff of the project, are responsible for this program. David G. Smith, under the direction of Harold C. Fritts, made summer collections and is assisting in dendroclimatic analysis. The investigation of tree growth through the study of anatomical development is being done by Marvin A. Stokes, with the aid and advice of W. S. Phillips, Botany Department, University of Arizona. Thomas P. Harlan collected preliminary core samples in 1961. Servicing of instruments, phenological notation, and anatomical sampling during the nonsummer months are done by the environmental measurement staff, James A. Erdman and Charles L. Douglas.

The environmental measurements study is the second-largest effort being made by the project. It interdigitates most closely with dendroclimatology, with plant and animal ecology, and with soil studies, as well as standing on its own feet as a desirable contribution to knowledge.

Six regional environmental measurement stations are located in varying latitudes or environmental situations. The first is at Park Point, the highest elevation in the park, the second is about midway down Chapin Mesa, the third is near its foot. Three others are located on the east slope, on the west slope, and in the bottom of Navajo Canyon, just west of the headquarters area. These stations are yielding full regional environmental data, and will provide a baseline for the ecological studies and for the dendrochronologically oriented studies of past climates.

Instrumentation, designed to allow rigorous comparison of the regional environments, includes 6 hygrothermographs, 6 three-pen thermographs, 2 recording pyrheliometers, 4 atmographs, 4 totalizing anemometers, 12 maximum-minimum thermometers, 1 psychron, 4 rain gauges, and 1 soil-temperature probe. This, together with the tree-growth instruments, totals 65 prime instruments, plus 14 check or evaluative instruments, used in measuring weather variation, soil temperature, and tree response. In addition to this, gravimetric analyses of soil moisture are made semimonthly at each station. All data are checked and key-punched for computer processing at the University of Arizona. James A. Erdman and Charles L. Douglas are responsible for this program, which is under the direction of John W. Marr, director of the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, University of Colorado.

Geologic work is limited to identification of raw stone materials once used in the making of artifacts and in the tempering of pottery. Sources have been located for the major categories. The studies have been done by Charles B. Hunt, Johns Hopkins University, the U.S. Geological Survey, and by the USGS laboratory at Denver through Leonard B. Riley.

Geochemical studies are limited, in this instance, to impurity analyses of human and turkey feces from the late (Pueblo III) occupation of the cliff dwellings. Spectrographic techniques are being used to measure manganese and phosphorous in the fecal material, and carbon isotopes measurements have been made at the Carnegie Institution's geophysical laboratory in Washington, D.C. The relative abundance of manganese is of climatic significance, and phosphorous provides a record of the general standard of nutrition. Bruno E. Sabels, formerly of the Desert Research Institute, University of Nevada, is doing this research.

Soil studies aim at providing a moderately detailed soil map of Wetherill Mesa and an understanding of local soils and their development. Orville A. Parsons, Soil Conservation Service, has provided invaluable data for plant and animal ecologists, for palynologists, and for tree physiology and environmental measurement studies. He likewise assists the archeologists with problems concerning soil profiles that are immediately germane to the excavation.

When the Wetherill project is concluded it will be abbe to present facets of local natural history and cultural history that will supplement each other interpretively. This archeological survey has resulted in a number of maps which detail the distributions of archeological manifestations of different periods. Soil studies and plant ecology will also result in soil and vegetation maps, and the environmental measurement research will yield climatic data. The park has been mapped topographically and geologically. The correlations of data yielded by these various studies, especially as recorded in the maps, should be enlightening.

Of major value to those scientists who are mapping all or part of Wetherill Mesa are the aerial photographs prepared by the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey. One set of photos is in color, the other in infrared. These yield data that cannot be obtained from conventional aerial photographs.

Zoology. Entomology, or archeological entomology, is the first category under "Zoology." This work was initiated on the basis of two hypotheses: (1) that insects are sensitive climatically and that a detectable difference between the faunas of the archeological past and of the present is significant, and (2) that food-products pests may have contributed to the difficulty that the last aboriginal population of the area had in maintaining itself.

A number of species that lived in the past, particularly wood-boring insects, are the same as those in the area today. Most of the insect remains obtained from excavations are fragmentary. These fragments are obtained by washing down adobe-clay from Pueblo houses. Identification of these fragments is very difficult, and this difficulty is increased by the fact that the present entomology of the area is poorly known.

This brings to the fore one of the difficulties of cooperative or interdisciplinary studies. One of the participants may logically require information of another that cannot be furnished, not because of methodological or technical incapability, but simply because knowledge is lacking. A full entomological study of the Wetherill area is required, but this effort is beyond the capabilities of the project. Samuel A. Graham, University of Michigan, who did this entomological work, has recommended a full-scale past and present study. So far, attempts to initiate such a program have not been successful.

Identification of scats found in protected cliff dwellings was done by the late Olaus J. Murie. His identifications control the samples that are sent out for parasite identification, for geochemical determinations, and for diet and ethnobotanical study.

Excavated mammal and bird bones are obviously a part of the past of Mesa Verde, as food bones or as artifact materials used by the Indians, or as remnants of more recent intrusions of wild creatures. It is usually possible to separate the two. All bones are identified, and those that are part of the cultural leavings will be used by archeologists in interpreting past Indian life. A second use, also of great value, will be for the ecological interpretations which this knowledge of past faunas yield. Lyndon L. Hargrave and Thomas W. Mathews of the National Park Service's Southwest Archeological Center are doing the identifications of bird and mammal remains, respectively. Hargrave also identifies feather and other avian remnants. Fragments of mammal debris, such as hair or hide, that require extensive comparative collections and laboratory facilities, are identified by the Federal Bureau of Investigation in Washington.

Modern animal ecology includes three phases, one of which is not modern except in that the distribution of present species will form a baseline for interpretation. Mentioned above are the basic data that can be derived concerning at best a part of the past mammal and bird life of the area from bones and other remains found in the ruins. Hargrave will compare past and present avian distributions, insofar as the collections will permit, and will interpret the results. The same will be done for the mammals by Charles L. Douglas. In the latter instance, the bone and fragment data will be somewhat increased by the identified scat collection.

The modern animal ecology research, which is being done by Douglas, consists of three major parts: (1) trapping small mammals (mice and voles primarily) and detailed examination of the mammals taken, (2) observations on larger forms with park population estimates, and (3) comparison of past and present species.

Trapping has been done at different altitudes, slopes, and in all of the major forms of vegetative cover, as recommended by the plant ecologist. Population densities and structures are being determined. As to the specimens themselves, research is concentrated on ectoparasites and endoparasites, skull and reproductive-system measurements, and stomach-content determinations. Slides have been made and photomicrographs taken of the plant epidermal patterns of the major vegetation areas at Mesa Verde. In this way the feeding habits of the trapped rodents can be most readily ascertained.

Botany. Plant-ecology researches are ordered in a similar manner. Actually the plant-ecology program was one of the first initiated, and it served as a model for the animal ecology program. It was originally intended to yield a modern baseline against which to project the information on ancient plant populations derived from cliff-dwelling excavations, and thus to make available some data on past environment through a knowledge of the plants living then. Another function of the ecologist was to identify the archeological plant remains. As in all the other studies, it was intended that the ecology should stand as a contribution in its own right.

As ecological studies and excavations progressed, it soon became apparent that James A. Erdman, ecologist, could not possibly cope with the thousands of plant specimens from the ruins, and at the same time carry on ecological studies and assist in the environmental measurement program. Other arrangements had to be made. Erdman's work now falls into three broad categories: (1) a descriptive treatise on the plant ecology of Wetherill Mesa; (2) preparation of a vegetation map of this mesa with the aid of vertical panchromatic, infrared, and color aerial photos; and (3) a statement on some of the ecosystem dynamics of Mesa Verde. Plant successions will be studied through the analysis of returning vegetation in burned areas.

The tree physiology-growth correlations have already been discussed above.

Agricultural plant studies depend upon identifications made in the field and laboratory and upon those made by the botanist. All fragments of cultivated plants (thus far these are maize, beans, squash, and bottle gourd) are sent to Hugh Cutler of the Missouri Botanical Garden. Cutler and his assistants are completing identifications and making interpretive studies of the agricultural plant remains in order to extract all possible data on the origin and kinds of agricultural plants and practices used by the Indians here.

Wild-plant identifications and archeological-ethnobotanical research are the responsibilities of Stanley L. Welsh of Brigham Young University. All plant materials, whether in situ in the ruins (lintels, wall pegs, and timbers) or fragments from the excavated fill are being identified. Although not insurmountable, one notable difficulty is the elimination of plant materials brought into the ruins by more recent mammal inhabitants, such as pack rats. Welsh is surveying pertinent modern ethnobotanies for comparative data on recent use of wild plants. This will enable him to interpret some aspects of prehistoric ethnobotany.

The mass of plant identifications will furnish data on the vegetal cover of the past and consequently will be of some value for climatic interpretation. Human and turkey scats have been washed down and fragments of plant materials from them sent to Welsh and his colleague, Glenn Moore, for identification and ultimate use in making statements about ancient diet. Quids, small wads of vegetation chewed by man, are being studied by Moore.

Summary. Reasonably successful development of this and other similar projects may be expected to have an almost revolutionary effect on the planning and prosecution of much of future archeology. I believe most anthropologists will agree that the study of prehistory offers tremendous opportunity for using the methods and content of many disciplines toward the solution of anthropological problems. Several major programs in the United States and in Mexico reflect this interest and indicate the will to attack the numerous difficulties involved. Unfortunately both interest and will have been of longer standing in Europe than in the New World.

Thinking in terms of human geography is not new in anthropology. It is new when we put those thoughts into action in terms of large programs of what is sometimes unfortunately called environmental archeology. I suppose these did not have to await the availability of extensive funds, in a absolute sense, but this is certainly the controlling factor now.

Archeologists are in a uniquely favorable position to continue to take the lead in many-pronged attacks on problems of breadth and depth. An archeologist's training and interests will press him, at one time or another in his career, into problems that are not satisfactorily illuminable by archeological techniques. More and more, archeologists are responding with massive concerted attacks on such problems, as at Mesa Verde, at Tehuacan, in New Mexico and Texas, in Arizona, and in Idaho. I believe that no other cultural anthropologist will range as widely or delve as deeply, unless he is an ethnologist or social anthropologist who has a truly deep interest and insight into the basics of economics.

The archeologist, if he will view his anthropological core-interest as a core only, if he will view the past and present not as Past and Present, but as simply aspects of a continuum and, further, if he will view human and other life in the area of interest as a sort of superecology, then, indeed, he will find himself well-equipped intellectually for a powerful attack on his old problems. The new ones that arise and the contributions that such studies make to the content and method of other disciplines are all there, and they are overtime pay. They enhance the values and the stature of our own study.

It seems to me that, in our thinking, we should, we must, blur the divisions of many of the life and physical sciences and try to refocus them on social, historical, and humanistic problems. Thereby we can take a leading part in anthropological development and therein we can contribute importantly to teaching and to anthropological method and theory.

Not the least of the rewards in developing a program such as the one at Mesa Verde is the opportunity to work with scientists of diverse backgrounds and to see their interests flare as the overlapping in their individual fields of study becomes apparent.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

archeology/7a/prologue1.htm

Last Updated: 16-Jan-2007