|

MESA VERDE

The Archeological Survey of Wetherill Mesa Mesa Verde National Park—Colorado |

|

THE ARCHEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF WETHERILL MESA

AN INVENTORY OF RESOURCES

ALDEN C. HAYES

purpose of the survey and methods of work

The objective of the archeological survey of Wetherill Mesa was to record the presence of all archeological manifestations in the area, to locate them as accurately as possible on a map, to describe each by means of field notes, sketches and photographs, and to make surface collections. Our work was a comprehensive survey. We recorded all prehistoric remains for which there was physical evidence on the surface of the ground.

An inventory of archeological resources of a given area is a prerequisite to any attempt to reconstruct that area's prehistory. A careful excavation of a single site will provide a wealth of detail concerning the cultural activity of that specific site; a survey will serve to relate that activity culturally and historically in time and space. Some form of site inventory has become part of standard practice in the archeological investigation of any new area. This has not always been true but as early as 1916 Kroeber (1916, p. 21) had this to say: ".... five thousand sherds can tell us more than a hundred whole vessels, and the bare knowledge of the average size of a room in a dozen contiguous ruins may be more indicative than the most laborious survey of two or three extensive sites."

In 1951 Don Watson, then park archeologist, instituted an archeological survey of the entire park as a long-range program. To date, over a thousand sites have been recorded on Chapin Mesa, which has been covered to the park boundary by James A. Lancaster. The survey on Wetherill, though stimulated by the requirements of the Wetherill Mesa Archeological Project, is a continuation of Lancaster's work on Chapin.

Plans for the future development of the park call for the excavation on Wetherill Mesa of a series of sites to be used as exhibits-in-place, illustrating to visitors the development of the prehistoric culture of the area from the beginnings of sedentary life until the final abandonment of the mesas by Puebloan people. By duplicating facilities already existing on Chapin Mesa it is hoped to serve better the ever-increasing public use of the park and, by a planned program of research, to increase our knowledge of the ancient life on the Mesa Verde and thus improve the interpretive program of the park.

The archeological survey plays a part in both the development and research aspects of the park plan. Survey is necessary to determine which sites, when exhibited, will best illustrate the various phases represented and, of course first, and if possible, what those phases are. The careful plotting of sites is required for the planning of necessary roads and trails in such a manner as to destroy as little as possible of the archeological and natural values which the park was established to preserve.

METHODS

The area covered by the survey included all of Wetherill Mesa from the escarpment on the north to the confluence of Horse and Navajo Canyons below the southern tip (maps 1 and 2). The eastern limits, from north to south, were the easternmost tributary to upper Long Canyon following the bottom of the watercourse, along the bottom of Long to its confluence with Navajo Canyon, and down Navajo to its juncture with Horse Canyon at the south end of the mesa. On the west the limits were the eastern tributary to East Fork of Rock Canyon into the main course of Rock and down the latter to its confluence with Horse Canyon and thence again to Navajo. The area thus defined is 10-1/4 miles long with an average width of a bit less than a mile. The total area surveyed was 6,274 acres, or 9.8 sections, of which 4,696 acres are within the park boundary and 1,578 on the Ute Mountain Indian Reservation.

|

| MAP TWO |

Like most arbitrary boundaries, that surrounding the park was laid out in relation to the stars with no regard to the shape of the earth on which it lay. The archeological survey attempted to encompass a geographic unit rather than a political one. Two parts of the mesa are on Indian lands: a short section immediately south of Rock Springs where the mesa is a narrow hogback, and the southern tip which runs 2 miles below the south boundary of the park.

In addition to sites within the area described, several cliff dwellings on the west side of Long Mesa and on the east bluffs of Wildhorse Mesa were surveyed, areas adjacent to our self-imposed limits. Also a week's reconnaissance was made on that part of Wildhorse Mesa that lies in the park's extreme southwest corner. The sites recorded outside the survey's limits described above are not considered in plotting site distribution.

A "site," as used here, is any place showing some evidence of aboriginal activity. The sites include habitations of any kind, isolated kivas and towers, shrines, firepits, sherd areas, reservoirs, check dams, pictographs, storage structures. Also included were a few historic campsites and hogans.

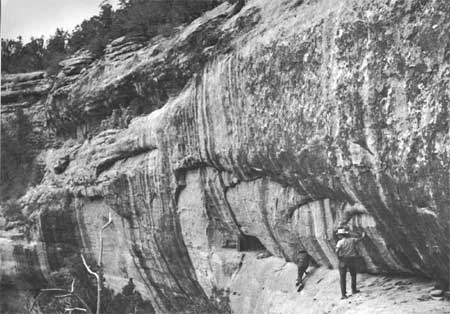

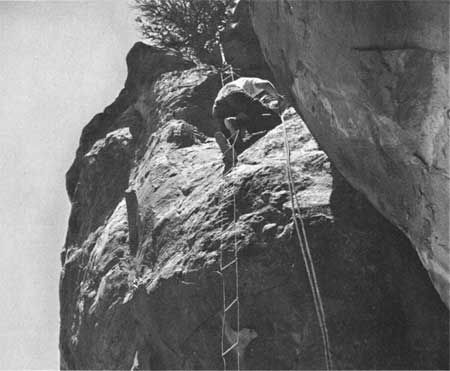

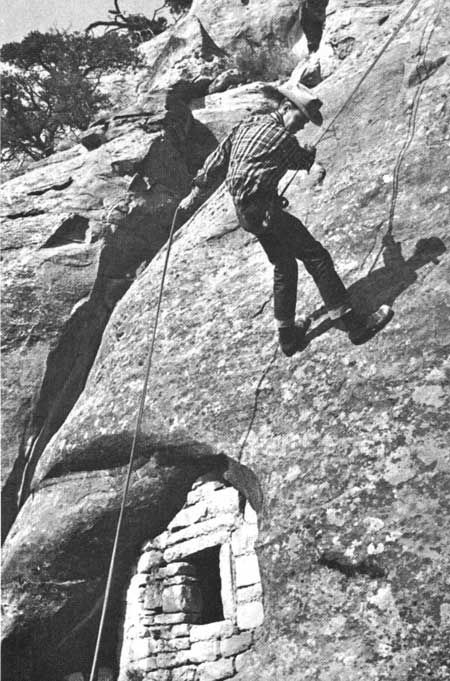

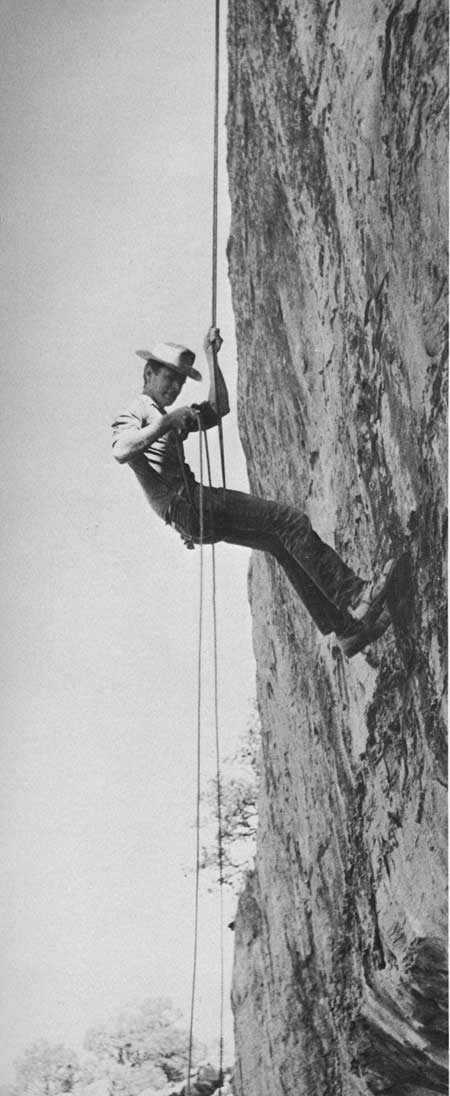

The Wetherill site survey was accomplished in 13 months of fieldwork during 1958-60. In the autumn of 1958 I worked alone in the relatively open, burned-over area at the north end of the mesa and recorded 116 sites. From April through October 1959 I surveyed the cliffs and canyons surrounding the mesa and was assisted during most of this time by five capable men: F. Jerome Melbye as foreman, John W. Wade, Curtis Schaafsma, Christopher Hulse, and Loren Haury. The party was usually divided into two groups, each led by either Melbye or myself. One group would work along the top, the other along the bottom, of the upper cliff. Small ledges between were examined by whichever party had the more feasible route (figs. 1, 2, 3). After a section of cliff 1/4- to 1/2-mile long had been covered, the entire party reversed itself and backtracked along the lower bluff below. The talus slope from the base of the lower cliff to the canyon bottom was then swept by the men in line at approximate 50-foot intervals. Most sections of canyon thus required four passes from cliff top to canyon bottom.

|

| Figure 1—Reaching small cave by old toe-and hand-holds and belay rope. Site 1350. |

|

| Figure 2—Survey party member, on steel rope ladder, prepares to explore small cliff ruin. Site 1709. |

|

| Figure 3—Entering Site 1246 on rappel from top of cliff. |

When a site was found, the crew, or a section of the crew, assembled on it and each performed a specific function. In this way the time spent at a site was cut to the minimum, and maximum control was exercised.

The U.S. Geological Survey topographic map of the park was found to be reasonably accurate, particularly as to cliff and canyon relationships, and site location was possible by means of hand-sighting with a Brunton compass to identifiable geographic features or cliff houses along both sides of the canyon. Field notes and sketches were made in an engineer's transit book. Sherds were collected in muslin bags equipped with drawstrings and cloth tags, which withstood handling and weather much better than the conventional paper sack. For photographs we used a 2-1/4-by-2-1/4 camera, which gave a negative identifiable without enlargement and was still light, easily portable, and, with its built-in exposure meter, speedy. On return to camp the data from notebooks were transcribed to a standard 8-by-11-inch field sheet while they were still warm.

In addition to collections of sherds, samples of stone chipping waste were picked up as well as all artifacts on the surface with the exception of metates, which were noted. Twenty-three dendrochronological specimens were secured from many of the sheltered sites, as well as numerous fragmentary examples of textiles and cordage and 30 wooden objects. Stone tools brought in included 60 projectile points or knives notched for hafting, and 37 grooved axes or hammers. From the surface 42 whole or restorable pottery vessels were collected.

Bird and mammal bones were sent to the Southwest Archeological Center at Globe, Ariz., for identification by Lyndon L. Hargrave and Thomas W. Mathews. Corncobs, cucurbit-rind fragments, and beans went to Dr. Hugh Cutler at the Missouri Botanical Garden for study. Species identification of plant remains, other than domestic, was made by Stanley L. Welsh of Brigham Young University.

During the early spring of 1960, before the snow was gone on the higher, northern sections of the mesa, Melbye and I worked the country on the reservation at the southern tip of the mesa. This was reached by way of the mouth of the Mancos River and up Navajo Canyon by jeep road to the mouth of Horse Canyon, where a temporary camp was made.

By the time the project camp was open early in May we were ready to work the heavily wooded mesa top. Our system had to be altered to fit the different terrain. Traversing the flat ground and finding a site was no problem, but accurate location of the site was another matter. Visibility through the woods is frequently limited to 50-100 feet, and on central parts of the mesa the ground itself is relatively featureless. To avoid the inaccuracies and great consumption of time inherent in estimating distances by pacing and by making a series of offset Brunton shots, a system of location by radio direction finder was devised. This involved the use of two low-power, tripod-mounted, portable transmitters placed over known points (fig. 4), and a small receiver which was carried to the site to be surveyed. Mounted on a compass rose and oriented to true north with the Brunton, the receiver was then tuned to each transmitter in turn and the two azimuths plotted. The radio direction finder made it possible to locate sites with reasonable accuracy and saved many man-months of labor (Hayes and Osborne, 1961).

|

| Figure 4—Transmitter and radio direction finder. |

The ground was covered by a "line of skirmishers" with intervals of about 50 feet between men. The man at one end followed a recognizable feature, such as the crest of a small ridge or the course of a shallow draw, and the others guided on him. On reaching the edge of the mesa or the particular spot to be covered, the entire line would wheel, reverse direction with the outside man on the first sweep following close to his own tracks and becoming the guide. Work in the dense brush required some degree of woodsmanship on the part of the crew members. Keeping orientation and interval while at the same time looking for archeological debris on the ground allowed no time for daydreaming. A crew of only four men was used. Contact and control was too difficult with a larger group. Crew members in 1960 were Melbye as foreman and Wade with experience from the first season, H. Anthony Ruckel, Virgil Higgins, and Billy D. Watson.

After completing the survey of Wetherill Mesa in late August 1960, we camped for a week in mid-September on Wildhorse Mesa, making a reconnaissance and recording a few sites. A total of 800 sites were surveyed including those in areas adjacent to Wetherill. Despite efforts to tabulate completely all sites showing any surface remains, possibly not more than 80 percent of the discernible sites have been recorded to date. In fact, since "completion," six more were found during the summer of 1961 on ground considered to have been thoroughly covered. Although the files must remain open for additions, the 806 surveyed sites offer far more than a random sample.

Sherds were studied twice in the laboratory. First, collections from each site were examined and typed. All sherds were then separated and studied by type or ware; i.e. all Mancos Black-on-white sherds were studied as a unit. Information on the site survey forms was transferred to 3-by-5-inch punch cards for easy analysis. Thus we could quickly determine, for example, how many and which sites in the cliffs had double-coursed masonry or what Pueblo I sites were situated on the talus slopes.

|

| Entering cliff-side ruin by rope. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

archeology/7a/survey.htm

Last Updated: 16-Jan-2007