|

MESA VERDE

The Archeological Survey of Wetherill Mesa Mesa Verde National Park—Colorado |

|

THE ARCHEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF WETHERILL MESA (continued)

terrain

The physiography of the area is covered by Osborne in the prologue. Briefly restated here, the Mesa Verde is a large uplift of sandstone and shales with a tilt to the southeast from a 2,000-foot scarp at the north. Erosion into the Mancos River, which cuts through the raised sedimentary rock, has formed numerous long canyons which cut headward to the north and leave almost equably narrow potreros or fingers of mesa between them.

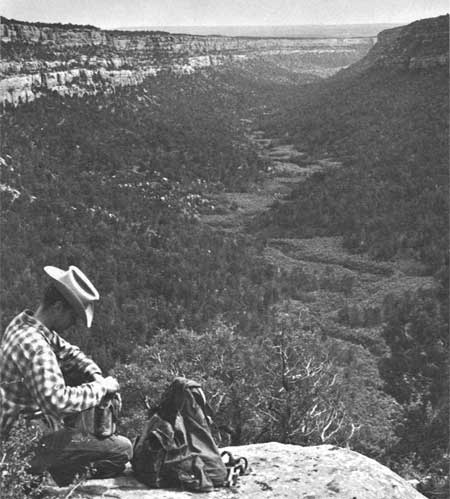

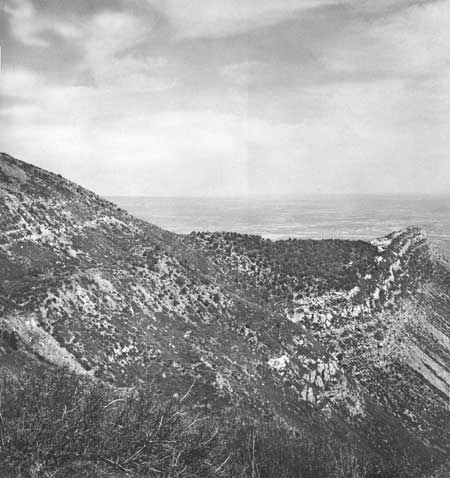

Wetherill Mesa, at the west side of the plateau, is a relatively insignificant landform throughout the northern half of its length. It is little more than a narrow hogback from the northern scarp to Mug House, averaging about a quarter-mile wide. In this section there is little level ground except in small patches on the ridgetop and at the confluence of small tributaries in the canyon bottoms. Cliffs are shallow at the heads of the canyons and are often cut into numerous stepped ledges; in some places they are covered by soil or worn down altogether. As we move south the canyons rapidly attain a depth of some 600 feet and maintain about the same drop to the southern end of the mesa. Where they have a respectable depth, two cliff faces are exposed with a short talus between them (fig. 5). Cover, for a mile or less south of the rim, consists of scattered stands of Gambel oak and serviceberry. The pinyon-juniper forest begins at about the 7,900-foot contour and increases in density and vigor southward. A fire in 1934 removed this forest cover from a point just north of Rock Springs to the scarp, and it has been replaced only by shrubby stands of serviceberry, fendlera, and rabbitbrush (fig. 6). A few struggling seedlings of pinyon indicate that regeneration without the proper nurse crop is slow. Soils in this area are mostly shallow and somewhat stony. Deeper brown loam occurs in such spots as gentle swales at the heads of drainages on the mesa or short benches below the cliffs in the upper reaches of the canyons.

|

| Figure 5—Looking South down Rock Canyon; Wetherill Mesa, left, Wildhorse Mesa, right. |

|

| Figure 6—Burn area of 1934. West Fork of Long Canyon in left center, Site 1173 in foreground. |

South of the vicinity of Mug House, at an elevation of about 7,200 feet, the mesa widens to a maximum of 1 mile; the country from this point south to the mouth of Bobcat Canyon is of a different character. Here the mesa is relatively flat and is covered with a red loess soil several feet deep near the center of the mesa. This soil decreases in depth at the edges of the cliffs where short ledges of bare sandstone are frequently exposed.

The cover on the mesa top is a pinyon-and-juniper forest with pinyon slightly dominant at the upper end of the area but giving way to a preponderance of juniper at an approximate elevation of 7,000 feet (fig. 7). The understory is predominantly low-growing bitterbrush and bunch grasses. The forest is unrelieved except by a long, narrow sagebrush glade in the drainage leading into Bobcat Canyon. Below the glade in the upper end of Bobcat Canyon is a small relict stand of ponderosa pine.

|

| Figure 7—Typical forest cover. House rubble of Site 569. |

The cliffs along this broader section of the mesa are sheer and deep, running from 50 to 100 feet in height with an average of about 65 feet. They are notched at intervals by rincons, indentations caused by small, ephemeral drainages off the mesa. The spot where water goes over the cliff is usually a broad area of exposed sandstone locally called a "pouroff." Two members of the Cliff House sandstone are exposed along the canyon walls, divided by a stratum of gray to black shale and a short talus slope. The lower cliff is usually shallower than the upper and composed of softer, more friable rock.

The two canyons bounding the mesa are slightly different in character. Rock Canyon to the west, due to the northwest-southeast run of the terrain, has more southern exposure on its left bank. Vegetation is open juniper and pinyon. This canyon is rather broad, and the talus below the lower cliff often bears relatively level benches or terraces. The bottom itself is frequently punctuated with small flat areas of deep alluvial soil covered with tall, dense stands of big sage. Long Canyon, to the east of the mesa, is narrower; north of the mouth of Bobcat Canyon, to the east of the mesa, the talus is steep. With its more northerly exposure and consequent lower evaporation rate, the right bank supports numerous thick stands of brush, primarily serviceberry and oak. The heads of many of the rincons, facing north, support small stands of Douglas-fir.

Below 7,000 feet and south of the vicinity of Double House the mesa again becomes narrower, the soil shallower and more calcareous. Extensive areas of bare sandstone are exposed, and the vegetation is more open with some increase in brushy species. Pricklypear and Mormon tea are more in evidence. The character of the cliffs remains unchanged but the talus on both sides of the mesa is benched and bears a cover primarily of bitterbrush. The mesa makes a slight turn to the south allowing winter sunshine to reach slopes on both sides of the mesa. Snow does not cling long in this region, and the browse affords a favored winter range for the mesa deer population.

For the last mile the mesa is a very narrow ridge cut by three volcanic dikes whose eroded channels provide an easy route past the cliffs. The southernmost of the dikes intersects a domelike "blowout," perhaps an exposed laccolith, of blue-gray rock which was used extensively by the Indians as flake material and for axes and hammerstones.

Permanent water sources are few. Eleven springs now produce water for part of the year. Of these, the strongest is in the bottom of Rock Canyon where the watercourse has cut through a sandstone member of the Menefee shale forming a pouroff in the canyon bottom. Below the drop a year-round spring produces water which trickles and stands in pools for 200 feet downstream, producing a small oasis of willow, cattail, and carrizo (Phragmites). That this spring has long been important is indicated by the concentration of ruins on the talus to the east and in the cliffs on both sides of the canyon.

Bobcat Canyon has two such drops over sandstone ledges, each with a spring which produces live water throughout most of the year. One is at the head of the canyon at the south end of the long sagebrush glade; the second is under a deeper pouroff about a quarter-mile north of Double House.

Rock Springs is the only spring used in recent years. It was a favored campsite for mustangers, cowboys, and early explorers. The National Park Service has built a small cabin there for the use of ranger patrols and smoke-chasers. It is perhaps not as strong a supply of water as the others mentioned but its location on the mesa top makes it more useful.

|

| Wetherill Mesa, looking south. |

The West Fork of Long Canyon also has two canyon-bottom ledges with periodic springs. The northernmost is 300 feet upstream from Site 1221, a canyon-bottom cliff dwelling. About 650 feet below Site 1218, another large cave site in the bottom of the canyon, there is a weaker spring or seep with a series of water-catching potholes in exposed rock in the channel just above it.

Two fairly constant water sources occur at the base of the upper cliff, forced out by the thin shale member of the Cliff House sandstone. One of these is at the rear of Long House cave, the other at the foot of the cliff below Site 1321. No water now appears on the surface at the latter site but the present tangle of carrizo and poison-ivy makes it almost certain that the removal of vegetation and the digging of a small reservoir would cause water to collect.

Three springs are on the talus, all on the west side of the mesa. Below Kodak House (Site 1212) in the decomposed shale of the short slope between the two cliffs is a constantly muddy spot and a growth of carrizo. A pocket dug into the mud will rapidly produce a small pool of water. A seasonal spring is in the lower talus slope only a short distance above the bottom of Rock Canyon in the watercourse of the draw below Jug House (Site 1233). In a location similar to that of the Kodak House spring but in the lower talus about 75 feet above the bottom of Horse Canyon is another spring, which goes dry in midsummer. It lies about halfway between the mouth of Rock Canyon and the confluence of Horse and Navajo Canyons and is the only water at the southern end of the mesa. It has been developed by the Utes to provide water for stock.

In addition to these fairly regular sources there are many spots at the foot of the upper bluff, at the juncture of sandstone and shale, where roots of brickellbush or serviceberry clinging to the rock along or into the seam indicate the presence of additional moisture. These places would probably produce surface water with only very little increase in the presently available moisture or if the earth were cleaned out and a rock catchment basin provided. One such point is in a shallow rock shelter 130 feet north of Site 1320; another is a small rincon 200 feet north of Site 1350. At the latter spot much moss and the fragment of a corrugated jar suggest a watering place. Just short of the southern tip of the long ridge between Bobcat Canyon and Long Canyon a "dry seep" occurs at each side of the mesa. Here the ridge is only 360 feet wide. The eastern of the two, on the Long Canyon side at Site 1362, is marked by a healthy cottonwood, a rarity on Wetherill Mesa, which grows with its roots in the rock of the cliff face. It is probable that, with considerably more human activity on the mesa and consequent reduced brush cover, more seeps and stronger springs were present in the 1200's. It is certain that the removal of phreatophytes from the immediate vicinity of a seep will, from reduced transpiration, increase the water yield (Hack, 1942, p. 13; Gregory, 1916, p. 129).

Other transitory watering places were supplied by the numerous small potholes in the sandstone on the mesa's edge and in the exposed rock in watercourses. Those in the West Fork of Long Canyon have been mentioned. Other outstanding examples occur in the bottom of Rock Springs Canyon near the juncture of its two forks, and at the pouroff above Kodak House.

The face of the north scarp at the head of Wetherill Mesa is marked by a ridge, Long Spur, which projects a mile into the Montezuma Valley (fig. 8, p. 32). Its steep slopes at the higher elevations bear a cover of pinyon and juniper with small stands of Douglas-fir. The shaly expanses lower down are mostly bare of vegetation. Because of the southward tilt of the strata no water can percolate to the north face, and no springs or seeps are present. The only known archeological site along the entire stretch of the north scarp of Mesa Verde is a one-room cliff house (Site 1222) at the base of Long Spur on its east side. There is no trash below it and so appears to have been little used. It must have been a 1-1/2-mile walk and a 450-foot climb to water. (Since this writing another cliff house was located).

|

| Figure 8—North Scarp of Wetherill Mesa with Long Spur to right. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

archeology/7a/survey1.htm

Last Updated: 16-Jan-2007