|

MESA VERDE

The Archeological Survey of Wetherill Mesa Mesa Verde National Park—Colorado |

|

THE ARCHEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF WETHERILL MESA (continued)

previous archeological work on wetherill mesa

The history of archeological investigations in the Mesa Verde area has been amply covered by Brew (1946) and brought up to date or synopsized by O'Bryan (1950), Watson (1954), and Reed (1958). An account of subsequent investigations can be summarized briefly. In 1953-55 Robert Lister, with a crew of students from the University of Colorado, excavated Sites 499, 866, and 875 on Chapin Mesa in the vicinity of Far View House. The forthcoming publication on these excavations will add to our knowledge of the Pueblo II—III mesa-top communities. Joe Ben Wheat of the University of Colorado Museum has worked for several seasons in a series of small sites with a long time span near the head of Yellow Jacket Canyon, about 15 miles north of Cortez, Colo. Results of this work, which still continues, have not yet been published. Salvage archeology, consisting of survey and several small excavations, was done along a pipeline from the Dolores River to the San Juan and through the Montezuma Valley by Albert Mohr and Laetitia Sample in 1956-60. A report of the work should be of great value but, as in many salvage operations, funds for fieldwork were not followed by sufficient money for analysis and report.

Within the park several small excavations have been made on Chapin Mesa in the past 10 years. In 1955 Ralph Luebben, Laurence Herold, and Arthur H. Rohn (1960) excavated an unusual Pueblo III masonry complex near Sun Temple. During the summers of 1957 and 1958 Luebben, Rohn, and Dale Givens (1961) excavated another Pueblo III structure near Cedar Tree Tower. Also in 1958 Rohn made a partial excavation of a Pueblo I pithouse and storage structure near Far View House. During the construction of a new pipe line east of park headquarters in 1959 two pithouses were discovered; both were excavated by James A. Lancaster (Hayes and Lancaster, 1962).

Until the commencement of the Wetherill Mesa Project in 1958, archeological investigations in the park have been confined almost wholly to Chapin Mesa, the largest of the flat-topped tongues of land, but since the early days of exploration it has been known that on Wetherill Mesa, between 2 and 3 miles to the west, existed the second most spectacular concentration of cliff dwellings within the park boundaries.

|

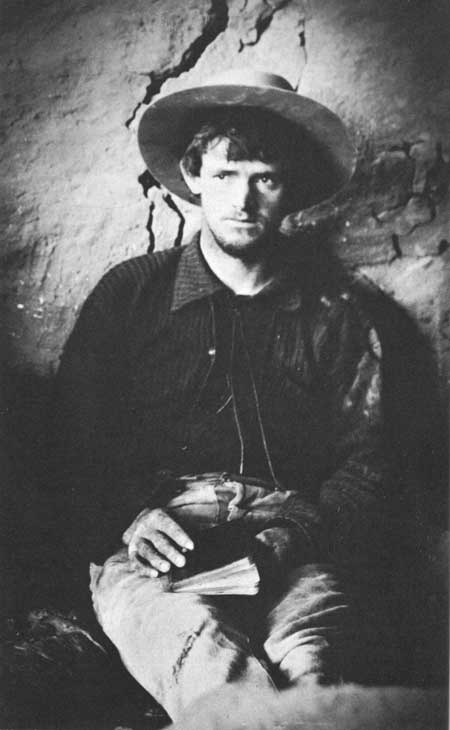

| John Wetherill, 1891. |

The first large herds of cattle were trailed into the Mancos Valley in the autumn of 1876 (Freeman, 1958). The wide-ranging longhorns, with cowboys not far behind them, probably wasted little time investigating their new country. It is very possible that some incurious rider had glimpsed most of the large ruins of the mesa before that stormy December day in 1888 when Richard Wetherill and his brother-in-law, Charles Mason, got their first view of Cliff Palace. For example, Bill Hayes, a cattleman and later justice of the peace, came to Mancos with those first cattle drives and left his name along with that of S. E. Osborne, a prospector, neatly carved on a doorsill in Hemenway House in Soda Canyon (which they called Bear Canyon) and dated the inscription "March 20, '84." Nevertheless, it was unquestionably the enthusiasm of the Wetherills which resulted in making the presence of the impressive ruins known to the rest of the world.

After their first cursory exploration in Cliff Palace and their subsequent discovery of Spruce Tree House and Square Tower House, Wetherill and Mason returned to their cow camp in Mancos Canyon where they encountered Charles McLoyd, Howard Graham, and Levi Patrick camped nearby. Their tales whetted the interest of the others who, along with more Wetherills—John, Alfred, Clayton, and Wynn—shortly rode back up Soda Canyon and spent much of the winter investigating the large ruins of Chapin Mesa. The deep sheltered canyons of the Mesa Verde were winter pasture and it was while looking after cattle during the stormy months that a cowboy had time to look for "relics." Summer took him back to the hayfields and to summer feed in the La Platas. During the fall of 1889, the men continued their explorations in Johnson Canyon, a tributary to the Mancos from the east side (McNitt, 1957).

|

L. C. Patrick C. W. 8-18-89 |

Some of the party apparently split off from the main body and worked back up onto the Mesa Verde again, this time farther to the west, for carved on the cliff face in a precariously situated cliff dwelling at the tip of Long Mesa (Site 1709) is the record: The C. W. is certainly Clayton Wetherill. Only a half-mile up Long Canyon from this spot, in Site 1445, also on Long Mesa, the two names appear again, this time without a date: here as "L. C. PATRICK" carved into the rock and "C. WETHERILL" written in longhand with charcoal. Since these two are the only sites in which the two names appear together, it seems probable they were made on the same excursion. Only a couple of hundred yards still further up Long Canyon from Site 1445 the men would have been able to see the impressive span of Double House; it is quite possible that they did and that they entered it. At any rate Clayton was able to report that there were fine prospects two canyons west of the mesa of their first winter's work, and it may have been this report that spurred an expedition to Wetherill Mesa in the early months of 1890. Clayton, John, and Richard Wetherill were members of this party; perhaps there were others.

Clayton was more obliging with complete dates than were his brothers. On a doorsill high in the upper level of Ruin 11 (Site 1325) in Rock Canyon he left "3-10-90 Clayton W," the earliest known date we have on the Wetherill Mesa since the 13th century. In the same ruin on a cliff wall someone, in more erudite vein, had carved "W MDCCCXC." The commemoration "Wetherill 1890" also appears in Ruins 12 and 13, in Ruin 11-1/2, Site 1370, and in Mug House. Mug House and Long House were both christened on this trip, the former because of the fine haul of those typical Mesa Verde vessels from there (Nordenskiold, 1893). Ruin 16 was visited that season as Nordenskiold recounts the Wetherills finding a mummy there. We know that a return was made the following year from the charcoal-scrawled "John & Clate Wetherill, 3rd 9 1891" in the upper cave at the west end of Long House. It is likely that all the major ruins on Wetherill Mesa were worked over during the winters of 1890 and 1891.

In 1891, in the tradition of Maximilian von Wied and many lesser European scholars of the period, Gustav Nordenskiold of Sweden made a western trip and, hearing of the Wetherills' discoveries, came to Mancos to see for himself. After a trip to Chapin Mesa via the Mancos River and Navajo Canyon, he was so intrigued by what he saw that he altered his plans and decided to spend the summer in more thorough investigation. He engaged John Wetherill as guide and foreman, hired two Mexican laborers, and packed in to Wetherill Mesa over a new trail only recently shown to the Wetherills by a friendly Ute. This route, though more difficult than the longer trail first used, climbed up the north scarp near its eastern end and followed the rim to the west. Wetherill Mesa, named by the 23-year-old scientist for John and his brothers, was chosen for his first work because his guide advised him it had been pawed over less than other areas on the tableland.

First camp was made at Rock Springs, and work was started at Long House with the intention of making a fairly complete excavation. After a month with rather disappointing results, Nordenskiold prospected at Ruin 16, around the corner to the northwest, then moved down the mesa for another try. The second camp location (Site 1834), still distinguishable by the remains of a firepit, cut poles, and a few sardine cans of the soldered-bottom type, was on the rim of Rock Canyon just south of Kodak House, so dubbed by Nordenskiold after their practice of caching a camera in one of the rooms. The canyon in front of him he called Mountain Sheep Canyon because of a bighorn sighted there. The name did not stick although bighorns are more numerous there today than they were then. John told him their one sheep was the first he had seen in 6 years.

Work was carried on simultaneously at Kodak House, Ruins 11, 12, and 13, with more encouraging results. Ruin 11, plastered precariously high on a cliff of soft, scaling sandstone, was difficult to enter. After the first ascent by toehold and fingernail, they braced a beam through a doorway, weighted the inner end with building stones, and from then on entered and descended by a rope from the outer, overhanging end. The same beam was very useful to the later survey crew of 1959. Although the digging was better here than at Long House, it still was not enough. Furthermore, water had to be packed 200 feet out of the canyon and over two cliffs from a muddy seep in the shale on the talus below. So camp was moved again after 2 weeks.

Nordenskiold wanted a virgin ruin, but the Wetherills apparently had left none. He was not convinced that it was necessary, however, and as his guides had had good luck at Mug House he set up his third camp on the ridgetop halfway between Mug House and Step House. The latter had not been worked but seemed rather unpromising. Water could be packed by horse from Rock Springs to the new camp, which had a more central location than the old one at the springs. This campsite, too, is discernible by the old cut stumps and a few glass sherds.

Nordenskiold was correct in assuming that Mug House would be a good prospect, as recent excavation there has proven, but he did not stay long enough to become aware of its potential because he had meanwhile discovered a very rewarding site in Step House. Here the remains of the pueblo produced little, but the refuse at the rear of the cave yielded eight burials. Digging into the area where pithouses were found 35 years later, but not recognizing a structure, he found a bowl and an effigy jar "of unusual type," so different from the ordinary run of pottery that he wondered if they might have been made by progenitors of the builders of large cliff houses.

While work was in progress in Step House, Nordenskiold also dug in Spring House across Long Canyon (which he cabled Spring House Canyon) and prowled around Double House, then known only as "Ruin 14," a number he had assigned. At Double House the difficult entry to the south end of the upper level of the cave was made when Clayton Wetherill threw a saddle rope across the two small projecting poles of juniper and climbed the rope. The same poles served the recent survey crew.

Clayton must have been an agile young man. The small ruin on the south tip of Long Mesa, Site 1709, where his initials appear with Patrick's name, was approached by the survey crew with high hopes. The only feasible access, down a 30-foot chimney over an additional 30 feet of cliff, aroused our hopes that we had not been preceded in recent centuries. Our equipment included a 30-foot steel wire ladder that is not usually part of a cowboy's equipment and certainly made entry safer if not easier. Finding Clate's initials was a disappointment.

After 2 weeks in and around Step House, Nordenskiold and his crew moved camp over to Chapin Mesa to investigate undug sections of the large ruins there. While on Wetherill, Nordenskiold made the first survey in which he numbered and described 12 cliff ruins and located them on a map. Eleven of these lie within the area covered by the present survey. Several, Ruins 11, 12, 13, 16, and 18, are still known by the numbers assigned to them in 1891. Nordenskiold published, with enviable speed, his Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde (1893), which to this date is the only scientific account of Wetherill Mesa archeology. In it he presented good house plans, excellent photographs of artifacts and structures, and some remarkably apt speculations. He suggested the purpose of the kiva ventilator shaft, recognized Basketmaker pottery as different from that typical of the cliff dwellings, and suggested its earlier place in a cultural sequence. He also described the masonry check dams and their probable place in native agriculture.

J. Walter Fewkes, who worked for many years excavating and stabilizing ruins on Chapin Mesa, did no work west of Long Mesa, where he excavated Daniel's House in 1915, thus clearing out what was probably the last remaining "virgin" cliff house of any size on the Mesa Verde. That he had visited Wetherill Mesa ruins is fairly certain, as one of his reports to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution recommended the excavation of Step House and its public presentation because of its interesting two-phase occupation (Fewkes, 1922, p. 71).

|

| In the early 1890's, Nordenskiold gave these ruins the name Kodak House, because of the expedition's practice of caching their camera in one of the rooms. |

The U.S. Geological Survey made a topographical survey of the Mesa Verde in 1910-11, noting the location of 54 cliff dwellings and "Pueblo Type" ruins within the area of our survey. Double House and a diffuse site in the head of Long Canyon (Site 1193) are indicated by the surveyors with three symbols each. In one instance a symbol for a cliff dwelling was placed at a cave in the rincon immediately north of Step House where no archeological site exists. Adjustment of these discrepancies leaves a total of 49 recorded sites, 11 of which were ruins already surveyed by Nordenskiold.

In order to learn more of the earlier occupants of the country and to add specimens to the scant collections of the museum, Jesse L. Nusbaum, then park superintendent, did some excavation in Step House cave in 1926. Three Basketmaker III pithouses were excavated at the south end of the cave. A manuscript recording this work awaits publication. The same party returned to Wetherill Mesa in the winter of 1928-29, again primarily to augment museum collections. During this season they dug in Long House and Mug House, in Ruins 12, 16, and 11-1/2, the last so named at this time because it lay between Nordenskiold's Ruins 11 and 12. Field notes by Marshall Finnan recording the excavation of a kiva in Ruin 11-1/2 are the only available records of the season's work (Museum Files, MVNP). That same winter Nusbaum did some extensive trenching in Site 1291, a large cave south of Step House containing several feet of recent alluvial deposit.

A forest fire in July 1934 burned for days and, before it was brought under control, swept bare the northern part of Wetherill Mesa from Rock Springs to the northern scarp. It also burned across Rock Canyon and Wild horse Mesa to the west and onto the upper part of Long Mesa to the east. During the fight to corral the blaze, a truck road was bulldozed on an old horse trail running along the rim from the automobile road at the head of Chapin Mesa, around the upper tributaries to Long Canyon, to Rock Springs and Long House. Prior to this time access to Wetherill Mesa was by foot or horseback. After the fire, in order to take advantage of the removal of cover, Park Archeologist Don Watson and Superintendent Paul Franke made a partial survey of the northern end of the burn, adding 13 previously unrecorded sites to the number of surveyed ruins.

Comparative ease of access afforded by the new fire road made it possible for James A. Lancaster of the park staff to transport tools and material to Wetherill Mesa, extending to that side of the park the stabilization work he had been doing on Chapin. In 1935, while getting adobe mortar for use in holding together a wall in Mug House, he discovered a "mummified" skull carefully buried in a small cave (Site 1228) a short distance north of the larger Mug House cave. Stimulated by Lancaster's find, Paul Franke and Robert Burgh excavated two rooms in the site, which they named Adobe Cave. Over a period of several years Lancaster also did stabilization work in Long, Step, Kodak, and Double Houses and in Ruins 12 and 16. In the process of stabilizing fragile walls he frequently gleaned bits of information about the ruins. His findings are recorded in the Stabilization File in the park museum.

As part of Gila Pueblo's Tree-Ring Expedition in 1941, Deric O'Bryan made collections and assigned Gila Pueblo Survey numbers to 14 ruins on Wetherill and 1 on Wild horse Mesa. Ten of the sites surveyed were cliff dwellings previously recorded by Nordenskiold, Nusbaum, or Watson. Five were small pueblos in the open on the mesa between Mug and Long Houses. Of these, because of rather vague locations given on the Gila Pueblo Survey sheets, we are able to correlate only one, Site MV:107 with Site 1553, in the current survey numbering system. The purpose of the expedition was the collection of dendrochronological material and in that it was successful. The work added to knowledge of cultural sequences and chronologies involved (O'Bryan, 1950).

In the early 1890's, Nordenskiold gave these ruins the name Kodak House, because of the expedition's practice of caching their camera in one of the rooms. Site 1212.

Table 1 correlates earlier site names and numbers on Wetherill and adjacent sections of Long and Wildhorse Mesas with the numbers of the park survey.

TABLE 1.—Correlation of various survey names and numbers

| Mesa Verde archeological site survey numbers |

Named ruins | Nordenskiold's numbers |

Watson-Franke survey |

Gila Pueblo survey |

| 1106 | 10 | |||

| 1109 | 11 | |||

| 1138 | 13 | |||

| 1139 | 12 | MV:154 | ||

| 1153 | 5 | |||

| 1154 | 1 | |||

| 1157 | 3&4 | |||

| 1159 | 6 | |||

| 1160 | 2 | |||

| 1169 | 7 | |||

| 1180 | 9 | |||

| 1200 | Long House | Ruin 15 | MV:132 | |

| 1212 | Kodak House | Ruin 22 | MV:131 | |

| 1228 | Adobe Cave | |||

| 1229 | Mug House | Ruin 19 | MV:118 | |

| 1233 | Jug House | Ruin 17 | ||

| 1240 | Ruin 18 | |||

| 1241 | Ruin 16 | MV:125 | ||

| 1285 | Step House | Ruin 21 | MV:134 | |

| 1320 | Ruin 13 | MV:148 | ||

| 1321 | Ruin 12 | MV:147 | ||

| 1322 | Ruin 11-1/2 | MV:150 | ||

| 1325 | Ruin 11 | MV:146 | ||

| 1355 | Plank House | |||

| 1385 | Double House | Ruin 14 | ||

| 1406 | Spring House | Ruin 20 | MV:119 | |

| 1448 | Daniel's House | |||

| 1449 | Ruin 20-1/2 | |||

| 1500 | Lancaster House |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

archeology/7a/survey2.htm

Last Updated: 16-Jan-2007