|

MESA VERDE

The Archeological Survey of Wetherill Mesa Mesa Verde National Park—Colorado |

|

THE ARCHEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF WETHERILL MESA (continued)

ceramics

The sherds collected on the survey received much handling. First, all sherds which could be classified were recorded on cards listing the types found on each site, just as they are listed in the tables in this report. During this phase of the work I was indebted to Arthur Rohn, who had been working for a year with the pottery from the Chapin Mesa Survey and who gave generously of his time and experience. I am grateful for his introduction to the local pottery; though I have borrowed many of his observations, I alone am responsible for the descriptions and interpretations which follow.

After the first classification by site the sherds were then divided and studied by types. When, as occasionally happened, I felt that I had initially called some things Mancos which should have been called Cortez, corrections were made on the site's pottery card. The descriptions which follow are of these specific batches of sherds compared with similar types described in the literature on Mesa Verde archeology. A reader with a strong interest in taxonomic system perhaps will be frustrated by my careless use of the words "type," "variety," and "ware." I use them as the dictionary defines them rather than according to any current system of ceramic taxonomy. As used here, a "type" is a "kind" of pottery—a group of vessels or sherds which have enough features in common to make it possible to identify them and to separate them from others, and which have a demonstrably significant niche in place or time. In some of the following discussions, I have speculated on how my types might be related to the common system of "type and variety." The frequent result of such an effort demonstrates the inconsistencies of typological frameworks which attempt to provide rigid rules for recording an activity which itself followed no rules in its development. The inconsistencies of the "typer" may be even more apparent.

|

| Pottery sorting tables. |

CHAPIN GRAY

The earliest and the basic pottery of Mesa Verde is a plain gray ware described many times. Hargrave in 1932 named the early plain pottery of northeast Arizona "Lino Gray," and Martin (1936) first applied that name to the similar ware of the Mesa Verde area. His lead was followed by Lancaster et al. (1954) and O'Bryan (1950). Abel (1955), recognizing the crushed-rock temper of the local gray ware, first used the name Chapin Gray to differentiate it from Lino Gray which was originally described as tempered with sand. Reed (1958) refers to it as "plain gray" recognizing the confusion that might exist if the Lino name should be applied. There does seem to be a spatial separation of the two tempering materials, the consistent use of rock temper being largely confined to the country north of the San Juan. If the differences were sand versus sherd tempering, the justification of a new type would be easier to accept. I am a little reluctant to admit cultural significance in a potter's use of coarse quartz sand rather than crushed rock. Local gray ware sherds mixed with Lino Gray sherds from the Klethla Valley or from Chaco Canyon cannot be separated without microscopic inspection of temper. In dealing with large numbers of sherds one gets a vague feeling that in the aggregate Lino may have a somewhat smoother surface with less scratching caused by dragging protruding temper during the smoothing process, but there is such a wide range of surface textures in both the sand and the rock-tempered vessels that a few sherds of one would be lost in a collection of the other.

In order not to overemphasize a slight difference and to avoid confusion in the literature, most of which refers to the local pottery as Lino Gray, one is tempted to suggest a compromise and call it "Lino Gray, Chapin Variety." An objection to this procedure is that it would make it a component of Tusayan Gray ware and would ignore the obvious continuity of the local banded-neck and corrugated types from the earlier plain pottery.

When the sherds from the surface collections were typed and separated, only a sampling of perhaps 20 percent of the total was taken. Close study was given to 1,553 plain sherds from 316 sites. Of this number many were undoubtedly from smoothed portions of banded-neck Mancos Gray vessels and even of corrugated jars of late periods. They differ only in percentages of large numbers of sherds. Plain gray sherds were found on 148 sites showing no other indication of Pueblo I or earlier occupation. Of these, 28 were apparently purely Pueblo III. Only those sherds which because of shape could be said with certainty to come from plain gray vessels were used to arrive at description and percentages. These included rim sherds, body sherds from neck and shoulder of a vessel, a few handles, and pieces of effigy vessels.

DESCRIPTION (of 1,553 sherds)

Construction. Probably concentric rings of fillets rather than coiling.

Paste. Light to dark gray with carbon streak on 11 percent of sherds inspected. Vitrified paste in 5 percent of samples. Temper: Medium-to-coarse crushed rock. Ninety-four percent of igneous rock, probably of alluvial cobble and characterized by large pieces of quartzite and smaller ones of black rock in the majority of specimens; 5 percent of an igneous rock containing much biotite mica, probably from intrusive dykes at south end of the mesa; 1 percent crushed sandstone. The latter could be confused with sand temper but for the presence of a few pieces of stone with the grains still cemented.

Surface. Color: Light cream to dark gray, most commonly light gray with fire-clouding on 7 percent. Treatment: Wiped or scraped, presenting a characteristically uneven or pitted surface with. bits of temper showing through. One percent of sherds showed some spotty polishing (remarks below). Fugitive red exterior common.

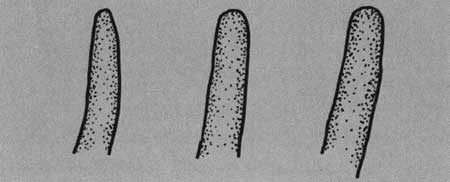

Shape. Seed jars, bowls, jars with narrow, vertical necks, half-gourd ladles, and eccentric or effigy vessels. Percentages of rim sherds collected indicates a preponderance of jars, 63 percent of total. Bowl rims 22 percent, seed jars 15 percent. Handles: Usually round in cross-section. Sometimes a thick, rounded strap. Handles frequently placed vertically on jars to make pitchers. Small, pinched nipple-lugs common; often perforated. Cylindrical lugs, flared at the rim with deep depression in the outer end. Rims: Rims were 80 percent either gently rounded or flat at the top. Apparently the potter drew the tip of her finger around the rim, frequently causing a bit of clay to be squeezed down on the side making an almost imperceptible "beading." Fourteen percent were flat on the outside but gently tapered toward the interior of the vessel (fig. 26). There is little variation in these percentages between the three vessel forms.

|

| Figure 26—Chapin Gray rim forms. Inside of vessel is at left, here and in all rim illustrations following. |

Thickness. Average 5.5 mm.; range 3-9mm.

Remarks. At Site 145 on Chapin Mesa, O'Bryan (1950) found that polished plain ware constituted 26 percent of his sherds. On the basis of these and collections made at Step House by Nusbaum's "West Side Expedition" of 1928 (no published data) he described a type called "Twin Trees Plain." This description is amplified by Abel. The Wetherill Mesa Survey produced 25 sherds of lightly polished plain ware. Seven of these are bowl sherds with an interior polish and are quite likely undecorated portions of Black-on-white vessels. Eliminating these, 19 sherds or 1.2 percent of the total exhibit a polishing which hits the high points of the surface, leaving scored areas and depressions untouched. Ten of the 19 come from Step House, one of the two type sites. Eight of the 315 other sites which produced Chapin Gray furnished the remaining 9 sherds. In view of its scarcity and its virtual limitation, as far as is known, to two sites, it is probably best to consider occasional polishing strokes a minor variation of Chapin Gray, and to suggest the elimination of Twin Trees.

Step House was perhaps occupied by a family or two of square pegs. The 5 percent of sherds showing a micaceous temper under the binocular microscope stimulated a curiosity to refer to the larger collection for the same thing. Visual inspection revealed the flecks of mica on the surface of 22 sherds of the entire collection. (Apparently it floated to the surface during the smoothing of the damp vessel as it frequently is evident on the surface when it cannot be found in a cross section.) Nineteen of the 22 came again from Step House; several of these were the unusual polished sherds. Lancaster and Watson (1942) also found a high percentage of micaceous grit at Pithouse B on Chapin Mesa.

At sites just 4 miles south of the tip of Wetherill Mesa Reed (1958) found Rosa Gray pottery. It would seem likely that it occurs on Wetherill but I cannot segregate it on the basis of written description and I have been unable to obtain sample sherds for a careful comparison.

MOCCASIN GRAY

Banded-neck unpainted pottery is considered the typical and diagnostic Pueblo I pottery in the Anasazi area. The practice of leaving the bands of clay unobliterated on the necks of jars seems to occur along with the deeper pithouses, the conversion of the antechamber into a ventilator shaft, and with the use of small adobe or jacal structures at the rear of the pithouses. Banded-neck sherds will occur only in small percentages on Pueblo I sites, however, as body sherds of banded-neck vessels are indistinguishable from Chapin Gray, which continued in the form of bowls and some jars. O'Bryan (1950, p. 92), considering just identifiable rim sherds, found that banded-neck pottery was 35 percent of the total gray ware on Site 102 on Chapin Mesa.

Moccasin Gray was named and described as a type by Leland Abel (1955) to differentiate it from the sand-tempered Kana's Gray of the Tusayan Gray ware series. Rohn (1959) considers Moccasin to be a variety of Chapin Gray rather than a separate type.

Banded-neck gray pottery, which appeared in the Four Corners area between A.D. 700 and 800; was the seed from which sprang the ubiquitous corrugated culinary ware of Classic Pueblo times. The progression from the wide bands of concentric fillets, through narrower fillets, unindented coils, to overall corrugated vessels provides a steady continuum which can be separated into types only on the basis of arbitrarily defined criteria. Separations in this continuum having any temporal significance are most difficult to make in the earlier phases and will be discussed in detail below in considering Mancos Gray.

Moccasin Gray sherds were found on 61 of the 128 Pueblo I sites surveyed. Only 116 sherds were collected and all were used in the study of Moccasin Gray on Wetherill Mesa.

DESCRIPTION (of 116 sherds)

Construction. Of concentric bands or rings.

Paste. Same as Chapin Gray. Carbon streak in 15 percent. Temper: Crushed rock. One sherd with addition of some sand to the crushed rock.

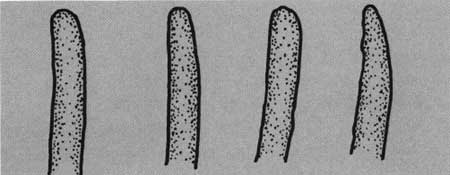

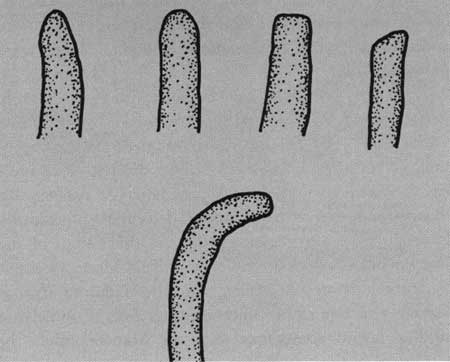

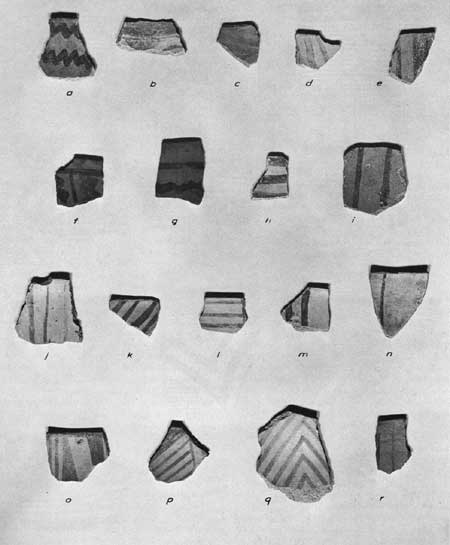

Surface. Same as Chapin Gray except that the bands of clay on the neck are purposefully left unsmoothed for decorative effect. Typically the bands lie flat and are sloppy and variable in width not only on the vessel but within a single fillet (fig. 27, a—d). The average band width is 12 mm. with a range of 8-18 mm. No treatment of the surface except for a trace of light wiping of the bands on a few with either the fingers or a bit of grass. Fire-clouding on 10 percent of the specimens.

|

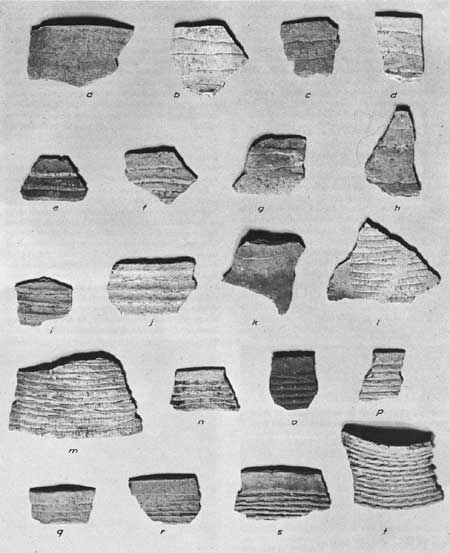

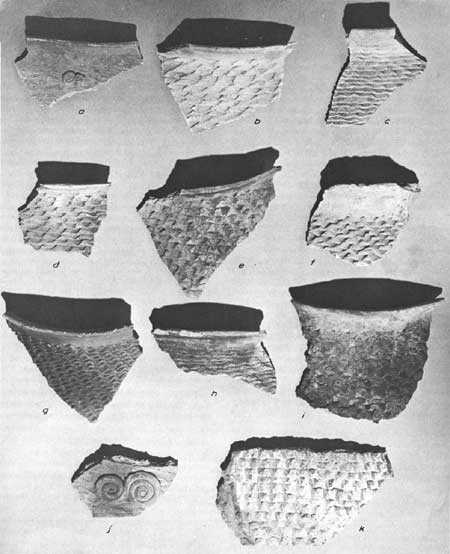

| Figure 27—Sherds of Moccasin Gray, a-d; Mancos gray, m-t; and possibly one or the other but typed arbitrarily, e-l. |

Shape. Jars, pitchers (one bowl sherd on which bands were not obliterated). Rims: Same as Chapin Gray with 87 percent either rounded or flat (fig. 28).

|

| Figure 28—Moccasin Gray rim forms. |

Thickness. Average 5.3 mm.; range 4-8 mm. Remarks. See remarks under Mancos Gray.

MANCOS GRAY

It has long been recognized that the transition from banded-neck pottery to the indented corrugated culinary ware derived from it was not cleancut and abrupt. Morris (1939, p. 185) illustrated sherds and vessels which show "the shift from banding through ridging to true corrugation." The technique displayed consists of the use of narrow, overlapped bands on the necks of jars with some instances of emphasizing the bands by tooling, drawing a line under the coil with a sharp stick. He believes the style to have been a short-lived one. Martin (1936) found, in the lower fill at Lowry Ruin, what he calls "plain (unindented) corrugated neck." O'Bryan (1950) found a few sherds of "coiled ware" at Site 34 but has little more to say about them. Brew (1946) records "plain (not indented) corrugated" sherds from Pueblo II levels on Alkali Ridge. But it was not until Abel's (1955) description of Mancos Gray that we had a convenient handle. The few such sherds brought in with the survey collections and their association with short rows of rooms of rough or cobble masonry and with Cortez Black-on-white would bear out the contention that it was made for a brief period, a transition ware in the banded-neck to corrugated continuum in early Pueblo II times. Parallel development in surrounding areas is represented by Coconino Gray in northeastern Arizona, by Clapboard Corrugated of the upper Pecos, and by pottery using identical techniques found by Judd (1954, pl. 50) in the old trash at Pueblo Bonito.

DESCRIPTION (of 128 sherds from 68 sites)

Construction. Coiled for the most part with probably some continuation of concentric banding.

Paste. Same as Chapin Gray. Carbon streak 4 percent. Temper: Crushed igneous rock.

Surface. Body sherds indistinguishable from those of Chapin or Moccasin Gray. Unobliterated coils on neck reaching down to shoulder of vessel (lower than on Moccasin Gray); average 5 mm.; range 3-9 mm. Coils frequently overlap with clapboard effect (fig. 27, e). Bottom of coil frequently emphasized by tooling. 17 percent fire-clouded.

Shapes. Jars only. Shapes approach the wide mouth, sloping shoulder of the later corrugated vessels. Rims: Round or flat as in earlier styles with some incidence of a very slight outward-flaring of the lip as on Mancos Corrugated. Rim usually an additional fillet.

Thickness. Average 5 mm.; range 4-6 mm. Note a slight decrease in thickness of vessel walls from Chapin through Moccasin to Mancos Gray.

Remarks. The sherds described as Moccasin and Mancos Gray above were those which were easily separated. Of the total number in the coiled or banded-neck series 37.5 percent were definitely Moccasin, 41.5 percent Mancos Gray. The remaining 21 percent were neither or both. Though unquestionably in the continuum, they were impossible to type without setting up an arbitrary set of criteria. These were:

|

Moccasin Gray Concentric filletsWide bands (8-18mm.) Rim formed by top band Smoothed by finger, if at all Bands lie flat Bands on neck only |

Mancos Gray CoiledNarrow bands (4-9 mm.) Rim an additional fillet Frequently tooled Clapboarded Bands sometimes below shoulder |

If features of a sherd match more items in one column than in the other, it can be given a name. As an experiment all but six of the indeterminate sherds were forced through this system and found a home. The results are less than satisfactory. In one case a Mancos Gray sherd showing the start of coiling at the base of the neck is obviously from the same vessel as a Moccasin Gray sherd which does not. A more realistic approach, and one which more closely reflects true ceramic history, is to admit that 21 percent of the sherds cannot be typed and that they represent progressive and regressive variants between two distinct styles (fig. 27, e—l). Such a large nameless percentage is a nuisance to the taxonomist but as a member of the species, I am reassured that human endeavor cannot easily be reduced to a formula and filed on punch cards.

The variation in treatment of bands or coils observed on these transitional sherds are: (1) Rather narrow bands ranging from 4 to 9 mm., smoothed along the band with thumb or finger frequently forcing up a ridge at point of overlap with the fingernail (fig. 27; h—j). This is the most common variation. The fact that it occurs in Pueblo I contexts (see Morris, 1939, pl. 219, f) might argue for calling it Moccasin Gray, but typing of pottery by its association defeats itself. (2) Bands smoothed over but site of the break marked or simulated by incised lines (fig. 27, k). Incised lines suggest Mancos but the average 10 mm. between lines has an earlier look. (3) Bands of medium width, of slight or no relief; showing incipient but probably accidental indentation. These could probably be slipped into Moccasin Gray by stretching the point that they all have narrower bands (8.9 mm.) than the described type (12 mm.). (4) Wide bands (9-15 mm.) with pronounced overlap or clapboard (fig. 27, e—g). (5) Wide bands (13 mm.) faintly incised at break.

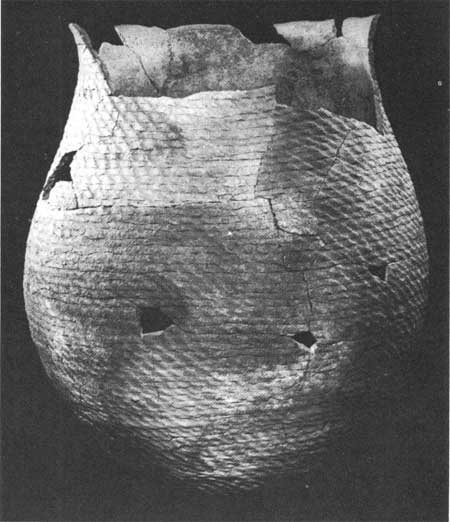

MANCOS CORRUGATED

The most ubiquitous pottery in the Anasazi area is the utility corrugated ware. It is also the most difficult to fit into time or place. Abel (1955) made an attempt to tie it down for the Mesa Verde by creating two types that he called Mancos and Mesa Verde Corrugated which, although recognizing difference in vessel forms, he differentiates mainly by the "heavier, rougher corrugations, diversity of treatment such as alternating plain and pinched coils" characterizing the earlier Mancos Corrugated. The more than 2,000 sherds studied from the Wetherill Survey showed little difference in treatment.

Rohn (1959) seems to have come much closer to the mark in relying primarily on vessel shape and rim form. It has been thoroughly demonstrated by all past field work in the area that a comparatively abrupt change occurred in shape from the straight or slightly flared rimmed, wide or "bell-mouthed" jar of Pueblo II times, associated with Mancos Black-on-white pottery and small pueblos, to the "egg-shaped" vessel with a narrow mouth and sharply everted rim of late Pueblo III associated with Mesa Verde Black-on-white, enclosed kivas, and large cliff houses. The descriptions that follow were based on a study of rim sherds that could be accurately typed, and by 28 whole or restorable vessels collected by the survey.

Before describing the corrugated pottery collected by the survey, I admit again that the shift from Mancos Gray, perhaps in the early 900's, did not come as a "mutation." Several sherds, at first thrown into the "corrugated" box, were in the end left unclassified. Although they showed incipient indentations, it could not be said definitely that the indentations were not an accidental result of pressing one coil onto another rather than an intended decorative device. The practice in early Pueblo II of making indented corrugations on the neck of a vessel but leaving the base smooth is well known and was a logical step to the final overall indented corrugated.

Reed (1958, p. 117) has suggested that the corrugated-neck pottery should be recognized as a separate type, significant as the transitional ware from banded-neck to allover corrugation. He included all Mancos Gray, however, with the banded-neck pottery. It seems to me that the decorative technique of indenting was a more significant step than that of failing to smooth over the coils at the base of the jar. The temporal significance of corrugated necks is valid only at the early end of the scale, as the practice continued to some extent throughout the occupation of the area. Half the sherds of this type (corrugated neck) that came from pure sites were from Pueblo III ruins.

DESCRIPTION (of 559 rim sherds)

Construction. Coiled.

Paste. Indistinguishable from Chapin Gray. Carbon streak 23 percent. Temper: 98.5 percent coarse-to-medium crushed igneous rock, 1 percent sand, 0.5 percent sherd.

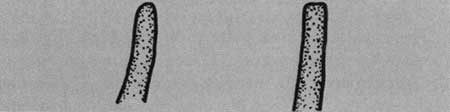

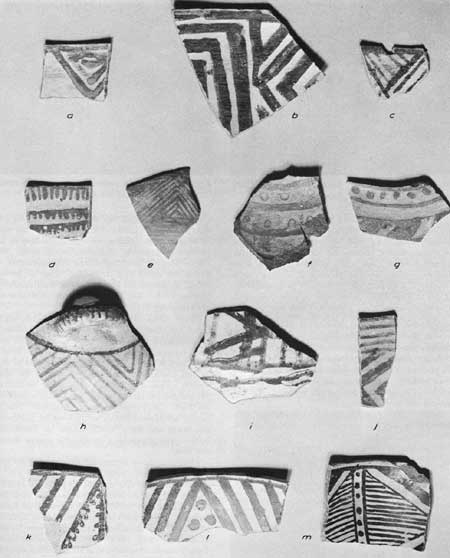

Surface. Corrugated. As the coils were pinched to the body of the vessel an indentation was made with the thumb. An almost infinite variety of surfaces resulted but they can be roughly sorted into four principal styles: (1) Plain indented: the depressions are staggered so as to fall between indentations on the coil below. This style constituted 78 percent of the total (fig. 29, a—f). (2) Diagonal ridge: in making the indentation the potter forced up a ridge of clay in front of the thumb. Since the depressions are staggered the ridges are also, with the result that a series of ridges sweep diagonally from rim to base with such prominence as to be more evident than the horizontal corrugations. This style is typical of Mancos Corrugated and does not occur later. It made up 14 percent of the total count. Since the diagonal ridges are seldom as prominent immediately under the rim, it is likely that many rim sherds called "plain" should raise this percentage if larger sherds or whole pots were available (fig. 29, g—i). (3) "Shadow" indented: 6.5 percent of the sherds are carefully but so lightly indented on flat bands as to be scarcely apparent. This is a style that continued through Mesa Verde Corrugated (fig. 29, j). (4) Patterned: varied treatments additional to the indentations (listed in decreasing order of occurrence), leaving one or more bands unindented, same but tooling the bottom of unindented bands as in Mancos Gray, smearing across the corrugations with the finger, incising across the corrugations. All these variations also are noted later on Mesa Verde Corrugated except the Mancos Gray style of tooling the unindented bands. Patterned variations were noted on only 2 percent of the rim sherds, but since the patterning is usually placed well down on the body of the jar, it probably occurs much more frequently. The numbers of patterned body sherds from purely Pueblo II sites would bear this out (fig. 29, k, l).

|

| Figure 29—Mancos Corrugated sherds. |

Occasionally an appliqué element of clay was added just below the rim, usually in the form of small, conical tits or an open, recumbent "S" (fig. 29, b). Fourteen and five-tenths percent fire-clouded. Average width of coils 4.14 mm. The painting of simple designs such as circles, squares, or bird tracks inside the jar near the rim, perhaps as the owner's mark, is common (fig. 30).

|

| Figure 30—Corrugated rim sherds with painted designs inside the rim—possibly ownership marks. |

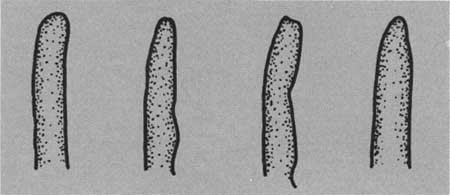

Shapes. Jars greater in height than in diameter with only slightly flared rims, and mouths almost as wide as the widest diameter (figs. 31-32). Bowls rare, with straight rims, often not indented. Rims: Rounded 67 percent, flat 23 percent, tapered or pinched 8 percent. Rim an unindented fillet averaging 15.5 mm. and ranging 9-26 mm. (fig. 33).

|

| Figure 31—Mancos Corrugated jar (cat. #13159/702). From Site 1344. |

|

| Figure 32—Mancos Corrugated jar (cat. #13180/702). From Site 1400. |

|

| Figure 33—Mancos Corrugated rim forms. |

Thickness. Average 5 mm.; range 4-6 mm.

Comparisons. See remarks below.

MESA VERDE CORRUGATED

DESCRIPTION (of 113 rim sherds)

Construction. Coiled.

Paste. Same as Chapin Gray or Mancos Corrugated. Carbon streak 36 percent. Temper: 97 percent crushed igneous rock, 2 percent sand, 1 percent sandstone and sherd.

Surface. Indented corrugated as in Mancos Corrugated and in the same styles with the exception of diagonal ridges. Some ridging occurs but rarely and in low relief, not predominating over the corrugations. Plain indented makes up 97 percent of the total (fig. 34, b—j). "Shadow"-indented or low-relief corrugations 2 percent, less frequent than in the earlier pottery (fig. 34, a). Patterned sherds (3 percent) included the very common alternating of several unindented bands with a wider series of indented bands but with no tooled emphasis of the division of unindented bands as in the preceding types. Also appearing, but in small numbers, are finger-smeared bands either across corrugations or following several coils so as to make a smoothed band around the vessel, tooled lines across corrugations, punctate dots or dashes, and incised patterns made with the thumbnail. Appliqued tits persist, but more typical is the common use of small fillets of clay applied under the rim as tight scrolls fig. 34, a and j). Twenty percent of sherds are fire-clouded. Identification marks in paint inside the rim continue (fig. 30).

|

| Figure 34—Mesa Verde Corrugated sherds. |

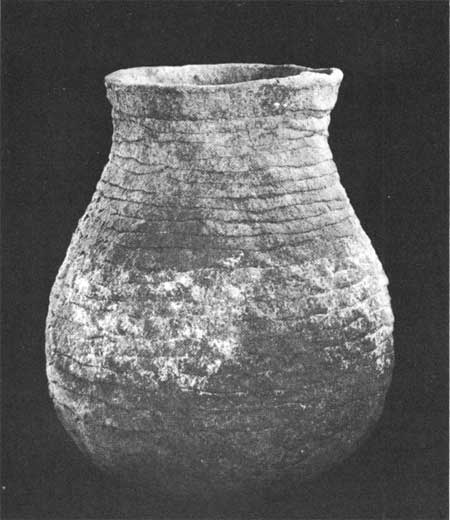

Shapes. Jars, squat or bulbous, egg shaped, with mouths often only half the maximum diameter of the vessel (figs. 35-36). Rims: Sharply everted, often 90° or less, to the wall of the jar below. Rim is formed of one or several fillets smoothed to a width ranging 10-38 mm. and averaging 21.5 mm. On 3 percent of the rims there was no smoothed fillet, but the corrugations extended to the outer edge. This practice may have been more common than this percentage indicates because 6 of the 26, or 23 percent, of the whole or restorable Mesa Verde Corrugated jars retrieved by the survey exhibit a corrugated rim. Rim lips are 62 percent rounded, 21 percent tapered; they supplant in popularity the squared or flattened rim which has slipped to 16 percent (fig. 37).

|

| Figure 35—Mesa Verde Corrugated jar (cat. #13146/702), found with McElmo Black-on-white bowl in figure 50. From Site 1308. |

|

| Figure 36—Mesa Verde Corrugated jar (cat. #13183/702). From Site 1433. Note smoothed band at mid-section. |

|

| Figure 37—Mesa Verde Corrugated rim forms. |

Thickness. Average 4.9 mm.; range 4-6 mm.

Remarks. A study of Wetherill Mesa sherd collections reveals but two traits, other than shape of body and rim, that can be used to distinguish Pueblo II from Pueblo III corrugated pottery. The presence of diagonal ridges or of tooled coil separations would probably preclude Mesa Verde Corrugated, but since the two traits combined did not make up 15 percent of Mancos Corrugated, their absence would leave the door wide open. To check the validity of the rim sherd counts, all the diagonally ridged sherds from the large collection of body sherds were checked for provenience. All sherds from mixed Pueblo II—III sites were thrown back, period designations being made on basis of combination of pottery and architecture. Only 6 of 128 were picked up on late sites; the large balance were from sites which appeared to have no occupation later than Pueblo II.

The same procedure was followed with patterned sherds—any sherds which showed surface decoration other than indentation of the coils. Of those coming from sites showing a single-phase occupancy, 71 percent were Pueblo II and 29 percent Pueblo III. The discrepancy is not as great as might be suspected. Since more Pueblo II sites were encountered on the survey, it seems likely that patterned variations were nearly as common on Mesa Verde Corrugated as Mancos Corrugated. Sherds of the alternate unindented tooled bands and indented bands came only from Pueblo II sites.

Heavy corrugation has been considered a trait of Pueblo II corrugated pottery (Abel, 1955). To check this the deeply indented body sherds were separated from the pile. After sherds from mixed sites were thrown back, 70 percent of the remainder were from Pueblo II sites and 30 percent were Pueblo III. When we consider that the ratio of Pueblo II to Pueblo III sites surveyed was 5:4, the disparity is reduced. Certainly deep indentations cannot be used as a criterion for separation of the types. In fact, on the basis of a smaller body of sherds, those of known type, 11 percent of the Mesa Verde Corrugated rim sherds were deeply indented whereas only 4 percent of Mancos Corrugated rims could be so classified.

Although vessel shape and rim form remain the best indicators of type for corrugated pottery, certain trends can be noted as changes in proportion, not only from Mancos to Mesa Verde Corrugated, but from Chapin Gray all the way through the Gray Ware series. Table 2 shows a consistent decrease in the number of vessels lacking an extra rim fillet, an increase in carbon streak and fire-clouding, and changes in emphasis in rim styles. A rounded rim was constantly the most popular. The flat rim, quite common on Chapin Gray, declined consistently throughout the series while the tapered rim was increasing in importance. It will be noted later that almost the reverse was true on decorated pottery.

TABLE 2.—Changes in emphasis in gray wares

T: Trace

| Ware | Carbon streak (%) |

Fire- clouding (%) |

Average width band or coil (mm.) |

Average width, rim band (mm.) |

Lacking rim fillet (%) |

Average thickness (mm.) |

Tapered rim (%) |

Rounded rim (%) |

Flat rim (%) |

| Chapin Gray | 11 | 7 | 100 | 5.5 | T | 49 | 37 | ||

| Moccasin Gray | 15 | 10 | 12 | 100 | 5.3 | 5 | 49 | 37 | |

| Mancos Gray | 4 | 17 | 5 | 14.9 | 26 | 5 | 7 | 59 | 33 |

| Mancos Corrugated | 23 | 14.5 | 4.1 | 15.5 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 67 | 23 |

| Mesa Verde Corrugated | 36 | 20 | 4.3 | 21.5 | 3 | 4.9 | 21 | 62 | 16 |

Another method of surface treatment, carried over from the times of Chapin Gray, is the removal of all evidence of corrugation. This pottery differs from Chapin Gray only in vessel shapes and in the fillet of clay added at the rim. Moccasin Gray is sometimes found with all bands rubbed out except the one at the top, but does not have the built-up rim characteristic of later gray wares. The plain—surface pottery is found with the shapes and rims of Mancos Gray, Mancos Corrugated, and Mesa Verde Corrugated and in the same associations as those types. It was probably made in small quantities after A.D. 900 through the late Classic period. Morris (1939, p. 93) found it in Pueblo III sites on the La Plata and considered it a smoothed variant of Mesa Verde Phase Corrugated. Rohn (1959), who found some of it in the Chapin Mesa survey collections, described it as Mummy Lake Gray. Body sherds cannot be distinguished from those of Chapin Gray, and he classified it as a variety of that type. The Wetherill Survey turned up only 10 sherds and 1 complete vessel from 7 sites. This is too small a sample to consider other than to record the occurrence. Seven of the 10 rims are the straight rims of Mancos Gray or Mancos Corrugated; 3 are sharply everted Mesa Verde Corrugated rims. These sherds were classified in the tables as either of the corrugated types according to rim form (fig. 63, f—j).

Perhaps because most of us are likely to describe what we find in a relatively small area without relating it with surrounding areas, there is confusion and overlapping of corrugated types in the Four Corners area. The corrugated pottery described above is called, after Abel, "Mancos" and "Mesa Verde." In Chaco Canyon the Pueblo II corrugated was named "Exuberant" by Roberts; the name "Chaco Corrugated" grew up around the later form. The similarities of Exuberant to Mancos and of Chaco to Mesa Verde are far more obvious than are any differences. These differences seem to boil down to the use in the southern types of sand temper predominantly, with some crushed rock temper and a little sherd temper. Our local ware is mostly rock tempered, some sand tempered, a few sherd tempered. A large sample of corrugated sherds from Chaco Canyon sent to us by Gordon Vivian would be lost if stirred up in the Survey collection. Differences in the aggregate of large numbers of sherds exist, but accurate typing of a few would be difficult if not impossible. Alexander Lindsay of the Museum of Northern Arizona, a visitor to our laboratory, thought it would be difficult to separate the local ware from the Tusayan with which he had been working. I will not attempt to defend the type names that I have used in this section, but what I have described as "Mancos Corrugated" is found on Pueblo II Ackmen and Mancos Phase sites and early Pueblo III McElmo Phase sites on Wetherill Mesa. That described under the heading of "Mesa Verde Corrugated" is associated with Pueblo III sites of the Mesa Verde Phase.

HOVENWEEP CORRUGATED

A late type of corrugated ware from Hovenweep and Hackberry Canyons on both sides of the Utah and Colorado boundaries has been described by Abel (1955) as Hovenweep Corrugated. It is a comparatively thick-walled type, frequently marked with vertical indentations giving a square rather than wedge aspect to the pattern. The vessels have a smeared or puddled appearance as though the coils were handled when wetter than was usual or if the surface were moistened after completion but before drying. The temper consists of coarse pieces of crushed sandstone at the type site. It occurs as only a small percentage of the corrugated sherds in collections from the Hovenweep area.

Sherds more or less answering this description (fig. 34, k) were found at six Pueblo III sites surveyed, and some of the material is turning up in the excavations at Long House and Mug House. The sherds were compared with sample collections from the Holly Group and from near Square Tower at Hovenweep National Monument. The Wetherill sherds have a temper of crushed igneous rock of particles larger than average. There is no reason to believe that it was not locally made. Reed (1958, p. 122) has suggested a possible influence from the southwest to account for it, Moenkopi Corrugated and Kietsiel Gray being cited as having some similarities.

LA PLATA BLACK-ON-WHITE

The earliest painted pottery on the Mesa Verde is the familiar Basketmaker III ware common to most of the Anasazi area. It was first described by Colton and Hargrave (1937) as Lino Black-on-gray, with quartz sand temper and a design applied in carbon paint. The first application of the name to the local Basketmaker III pottery was made by Martin (1936) in his work in the Ackmen-Lowry area. Hawley in 1936 described La Plata Black-on-white as a mineral-paint eastern corollary to Lino Black-on-gray. Recognizing that the early pottery on Mesa Verde made use of both, or either, mineral and organic paint, Lancaster and Watson (1954, p. 19) and O'Bryan (1950, p. 105) used both terms depending on the paint type.

In an attempt to clarify the taxonomic confusion Abel (1955) renamed and redescribed the type as Chapin Black-on-white with mineral paint- and rock temper. The descriptions for both Lino and La Plata called for sand temper almost exclusively. This still left organic-painted, rock-tempered Basketmaker pottery uncovered by a type name. However, to avoid complete fragmentation of what is, on the basis of design and vessel form, an easily recognizable and essentially homogeneous type throughout the northern Southwest, Rohn (1959) accepted the name "Chapin B/W" but redescribed it to include organic-painted design.

Although incompletely described, it was apparently the Basketmaker pottery of the Mesa Verde to which Hawley referred in her Field Manual of Prehistoric Southwestern Pottery Types (1936). She gave credit for the name to Gladwin (1934), who used the name "La Plata Phase" for the San Juan Basketmaker and for type sites referred to MV: 27 of the Gila Pueblo Survey, and to Morris (1919a). MV: 27 is a Basketmaker III—Pueblo I site on Chapin Mesa about a mile from park headquarters. Morris. was describing Basketmaker pottery from the La Plata River approximately 20 miles southeast of Spruce Tree House. From his and Shepard's (1939) painstaking analysis, it is obvious that local Lino-Chapin-La Plata Black-on-white is the same ware.

The earliest decorated pottery on the Mesa Verde as shown by the Wetherill Mesa Survey collections occurs in the following variations:

organic paint—sand temper

organic paint—rock temper

mineral paint—sand tempermineral paint—rock temper

mineral (glaze) paint—rock temper<

mineral (glaze) paint—sandstone temper

organic and mineral paint—rock temper

I have not examined a sherd with mineral paint in an organic medium that contains sand temper but I have no doubt that one will turn up. All these variations in the same design tradition, with no apparent spatial or temporal significance, I am here calling La Plata Black-on-white, recognizing Abel's mineral-paint, rock-tempered Chapin as a variety that is predominant in this area. Either name when used on Mesa Verde would be correct in most cases. This seems to be an evasion and it is. All attempts to settle the termninology have been based on survey and relatively small numbers of sherds. The Wetherill excavations are expected to furnish more material with stratigraphic associations. A breakdown of variants and a complete taxonomy should be postponed until that material can be examined.

My acceptance of the separation of Chapin Gray and Moccasin Gray from the sand-tempered Lino and Kana'a Gray is an apparent inconsistency. Perhaps it is, and perhaps they too should be considered as varieties; but the difference in temper in plain wares represents half the criteria available—temper and vessel form. With the addition of paint on decorated pottery, temper becomes only one of four criteria, because with paint we have also gained design. The importance of the change of temper should not outweigh the value of the sum of the other three factors, which, in the case of the local Basketmaker III painted pottery, remain unchanged from La Plata Black-on-white.

Twin Trees Black-on-white (O'Bryan, 1950; Abel, 1955) is also included in the description below. Slightly polished sherds in all combinations of paint and temper are found on Chapin as well as Wetherill Mesa from Basketmaker and Pueblo I sites.

DESCRIPTION (of 99 sherds from 60 sites)

Construction. Probably of concentric rings as in Moccasin Gray.

Paste. Same as Chapin Gray, light to dark gray, some with vitrified paste. Temper: 96 percent crushed igneous rock (one sherd contained sandstone), 3 percent sand. Carbon streak 29 percent.

Surface. Light cream to dark gray. Scraped and smoothed. Eleven percent show rubbing marks and reflect a little light from high points on the surface. Five percent might be called polished. Fire-clouding on 10 percent. Most rubbing is on bowl interiors. Exteriors of most sherds indistinguishable from Chapin Gray.

Shapes. Ninety-one percent bowls. Four sherds of narrow-necked jars or pitchers and one seed bowl. Rims: As in the plain gray ware of the same period, 88 percent of the rims are gently rounded or flat (fig. 38).

|

| Figure 38—La Plata Black-on-white rim forms. |

Thickness. Average (of 50 sherds) 4.5 mm.; range 3-6mm.

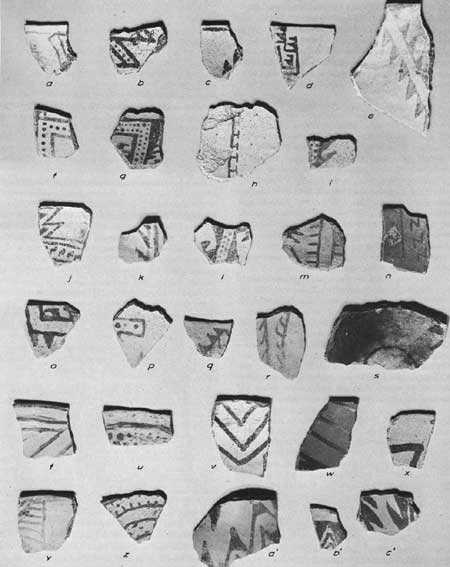

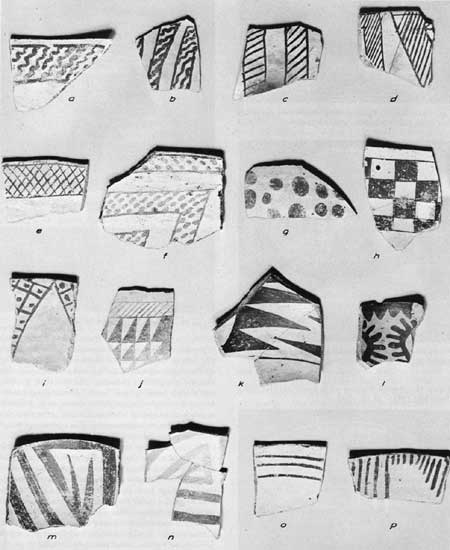

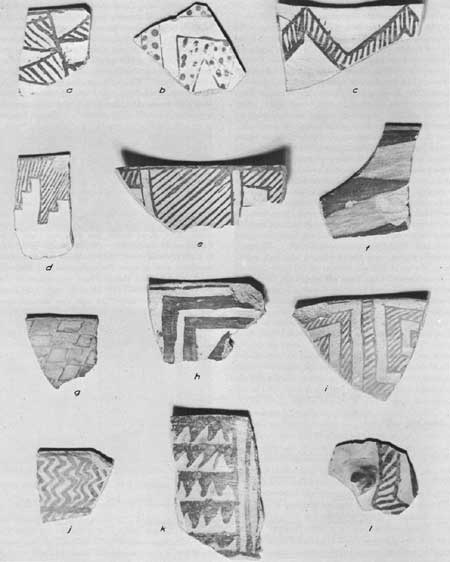

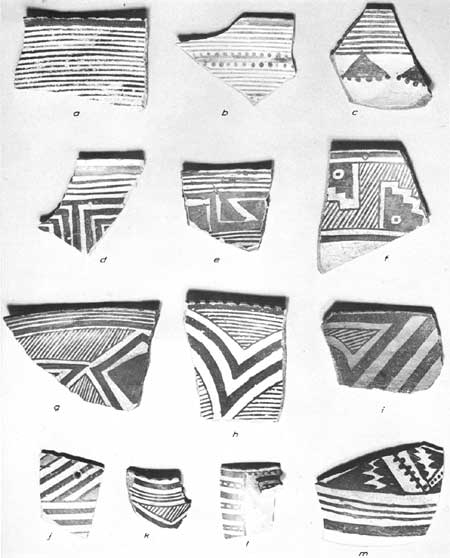

Designs. Lines of dots, Z's, crosses, flags, hooks or small triangles, frequently framed by parallel lines, radiating out from the bottom of the bowl, frequently from a small circle (fig. 39, a—s). The bowl is thus divided into two, three, or four sections. Design is centered on and oriented to the bottom of the vessel. Two bowl sherds had exterior decoration: one a short, slanting line just under the rim, and the other a deer or mountain sheep. Twenty-five percent with solid painted rim. Paint: 79 percent mineral paint including five sherds with glazed paint in which vitrification was apparent. Color ranges from black, to red on the numerous oxidized pieces, and to an almost emerald green on the glazes. Eight percent organic paint; 7 percent showed evidence of a paint containing both organic and mineral elements; 6 percent could not be determined.

Remarks. Despite the variety in paint and temper there is no reason to believe that any of the above sherds were made elsewhere. One of these was an organic-painted, sand-tempered sherd which one could argue should more properly have been typed Lino Black-on-gray, but the sand was not the distinctive white quartz of northern Arizona temper, consisting instead of rounded grains of black, brown, and cream-colored grains such as can be found along the Mancos River. In assigning sites to a period, I consider La Plata Black-on-white diagnostic of Basketmaker III and Pueblo I. It was the only decorated ware of the earlier period but continued to be manufactured for some time after pithouse antechambers became narrow ventilator shafts and the houses themselves were backed by crescentic rows of jacal, adobe, and rough masonry rooms. It was the only decorated pottery picked up on many Pueblo I sites.

PIEDRA BLACK-ON-WHITE

Piedra Black-on-white, along with Moccasin Gray, is the diagnostic pottery type for a Pueblo I occupation of a site in the Mesa Verde area. Although Basketmaker III design styles were remarkably similar throughout Anasazi country, some regional differences show up in the eighth century. South of the San Juan some form of the White Mound-Kiatuthlanna-Kana'a style was the Pueblo I preference. This style does not make its appearance until about A.D. 900 on the Mancos and La Plata Rivers, where the Pueblo I decorated pottery continued the La Plata Black-on-white tradition with refinement and a changing approach to design layout. Relationship to the upper San Juan drainage was stronger than to the Chaco at this time.

The type was named by Mera (1935) in referring to the Pueblo I pottery excavated by Roberts (1930) on the Piedra River. Mera includes it as a component of the Gallina series.

As the type is a further development of La Plata Black-on-white and as changes were gradual, it is not always possible to separate Piedra from La Plata. Piedra Black-on-white is sometimes polished. The same design elements were used, and the differences in composition are not always apparent on sherds. About 25 percent of the sherds in the survey collection which were either La Plata or Piedra could not be separated further.

DESCRIPTION (of 68 sherds from 43 sites)

Paste. Like La Plata. Carbon streak common, 9 percent. Some vitrification. Temper: Fine-to-coarse, crushed igneous rock. One sherd with sand temper.

Surface. All but 10 percent show some degree of polish, with many (12 percent) bowl sherds also showing some extra rubbing on the exterior. Slip: 10 percent of bowl sherds give appearance of having been slipped. At least three sherds have a true slip, the others may be floated. No indication of slip on other shapes. One bowl and one jar with unobliterated bands as in Moccasin Gray. Fire-clouding 9 percent.

Shapes. Eighty-three percent bowls. Jars or pitchers, squash pots represented. One large jar with a round handle as on Chapin Gray. Rims: As in La Plata Black on-white, 86 percent either flat or gently rounded.

Thickness. Average (of 50 sherds) 4.7 mm.; range 3-7 mm.

Design. Generally much like La Plata Black-on-white, with same elements of design but with more refinement and more elaborate layout. Pattern usually dependant from the rim rather than centering at bottom. Frequently banded. Emphasis on triangles and parallel lines and lessened use of dots, hooks, and flags. Suggestions of pre-Gallina in use of parallel banding lines. Some use of nested or concentric characters or rectangles. Forty-three percent of rims painted. One sherd with paint on bowl exterior. Paint: Mineral in all but 4 percent. Light gray to black. Mostly a pale "shadow" gray. The oxidized reds and browns common on La Plata quite rare here. Examples of Piedra Black-on-white are shown in figure 39, t—c'.

|

| Figure 39—La Plata Black-on-white sherds, a-s; and Piedra Black-on-white sherds, t-c1. |

Remarks. Piedra Black-on-white differs from its predecessor and parent (it is hard to avoid genetic terms) in this area mainly in design layout, which is difficult to recognize from sherds alone. Other differences are matters of trends which can be expressed in percentages but are of little value in typing a single sherd. Polishing has increased from "some" to "most," and a slip makes an appearance. The use of sand temper and organic paint has decreased. A larger percentage of rims are painted, and decorated jars and pitchers have increased. Morris (1939, p. 177) expresses the difficulty of describing design on Pueblo I pottery on the La Plata: "Painted ornamentation of pottery was still in its formative stage and in consequence remarkably fluid and variable. Obviously there were certain trends but these had not become sufficiently crystallized to herd the pot painters into any definite or restricted path." It should be noted that Morris found no organic paint on his Pueblo I pottery.

The written history of Piedra Black-on-white presents some contradictions. O'Bryan, who made the first careful excavations of Pueblo I sites on the Mesa Verde, lists Piedra Black-on-white as a Pueblo I painted type and illustrates sherds that seem to fit the description given here for the type (O'Bryan, 1950, p. 92, pl. 42). Abel (1950, p. 5), however, would not accept Piedra as a local type because Roberts' pottery from the Piedra River originally was described as sand tempered. To cover the gap from Basketmaker III to Pueblo II on the Mesa Verde he described Twin Trees Black-on-white and gave it a longer time span, but ignored the changes in design that occurred. Reed (1958, p. 80) saved the name from threatened oblivion but includes as Piedra some pottery that here is described as Cortez Black-on-white, a type that had not been separated at the time he made his analysis. He found it associated with banded-neck pottery but he included in his banded neck the narrow coil, tooled and clapboard Mancos Gray (Reed, 1958, p. 115). Again, it had not yet been demonstrated that the latter had a temporal separation from the earlier Moccasin Gray.

Abel, as we have seen above, placed strong emphasis on the temper of pottery and on the basis of sand temper in Piedra Black-on-white in the original description assigned it to the Chaco Series, as Colton did in his Check List of Southwestern Pottery Types (1955). In her examination of the pottery at BC 50-51, Hawley (1937, 1939) did not find Piedra Black-on-white part of the Chaco Canyon pottery complex. Hawley (1936) considers Piedra Black-on-white the Pueblo I pottery of the Piedra, Largo, and Gobernador drainages. As a result of their recent work in the Navajo Reservoir area, Dittert, Hester, and Eddy (1961, p. 232) are able to concur with Hawley. Some of us from the Wetherill Mesa Project had the opportunity of examining pottery from the upper San Juan in Santa Fe and discussing it with Dittert. The Piedra Black-on-white from that area is not as varied in design as that from Mesa Verde and is largely made up of simple parallel lines. There it is considered part of the Rosa Gallina series. It is not unreasonable to accept Piedra as a component of two groups of pottery. It is a sand-tempered transitional form in the east, between Rosa-La Plata and Gallina-Arboles; in the west, with rock temper, it falls between La Plata and Cortez Black-on-white.

CORTEZ BLACK-ON-WHITE

We have seen, in the decorated pottery of the Pueblo I period here, the beginnings of the use of the concentric triangles, chevrons, and rectangles which were a dominant feature of Pueblo I pottery to the south. This style, as displayed on White Mound and Kiatuthlanna Black-on-white to the south, and on Kana'a to the southwest of Mesa Verde, made an impact in this area somewhat later and combined with the scalloped or ticked solid triangles and frets of the southern Red Mesa or Chaco Transitional style. These influences, plus a continuation of Piedra design elements, made up the characteristic early Pueblo II pottery of the Mesa Verde. The type was named Cortez Black-on-white by Abel (1955).

Previously it had been considered part of Mancos Black-on-white by O'Bryan and by Lancaster and Pinkley (1954, p. 70, pls. 47, 49, 50, 52, 53), although they admit the possibility of a separation. Morris (1939, p. 191) mentions the great similarity of his Pueblo II pottery to the earlier ware of Kiatuthlanna and describes and illustrates vessels generally quite distinct in design from later decorated pottery but assigns no names. In his survey on the Mancos River, Reed (1958, p. 81) found that "occasional sherds are difficult to place definitely between Piedra and Mancos, and a distinctive group decorated in squiggled hachure seems to be transitional." He recognized a wide range of styles in Mancos but did not feel there was enough evidence on hand to justify a split of types. He mentions Piedra sherds with a tooled-coil exterior. The tooling of coils is a Mancos Gray trait and is considered here as early Pueblo II. What is here described as Cortez would include some of Reed's Piedra and some of his Mancos.

Prior to Abel's description, Martin (1936, p. 104), in his work at Lowry Ruin, was the only fieldworker in the area to attempt to separate the type. He found it in the lower levels of the excavation underlying his Mancos and McElmo and referred to it as Red Mesa, considering it to be intrusive from the Chaco country. Certainly the similarities of Cortez to Red Mesa are more striking than the differences, and a good case could be made for calling the former a mere variety of the latter. In spite of the fact that the design style is often identical, Cortez pottery differs from Red Mesa in its superior slip and polish and is definitely part of the local continuum despite the borrowing of design elements.

I believe Abel's establishment of the type to be a valid contribution which recognizes a style with definite spatial and temporal implication. Cortez Black-on-white is found only on Pueblo II sites and is associated with houses of rough masonry constructed in straight rows of rooms or ebbs, and with Mancos Gray, corrugated-neck straight-rim gray ware, and straight-rim Mancos Corrugated. The difficulty lies, as it does with every other type, in our inability to type all sherds. Since many Piedra elements were continued on Cortez and many elements adopted on Cortez continued in use on Mancos, a large body of sherds at each end of the scale must remain undetermined as to type. Cortez, manufactured for a comparatively short time, is a valuable diagnostic type, and one should be fairly demanding in recognizing it in order not to destroy its value. All sherds in the survey collections which exhibited features found on both Cortez and Mancos but none which seem to be purely Cortez were called either Mancos or were not named—accounting for the greater amount of Mancos Black-on-white in the sherd counts for Ackmen Phase sites. The current excavation of Badger House, an early Pueblo II site on Wetherill Mesa, is turning up great quantities of Cortez Black-on-white. Soon we should have a better description of the type and of its place in the picture.

DESCRIPTION (of 921 sherds from 162 sites)

Paste. From almost white to dark gray. Generally somewhat finer than in preceding types. Carbon streak on 29 percent; less common on jars than on bowls.

Temper: Mostly crushed igneous rock, considerable sherd temper, and some of sand (see remarks).

Surface. Ninety-five percent of sherds were slipped and polished; 77 percent of bowls slipped on both inside and out. Slip usually thick and white and often with fine crackling. Three percent of bowl sherds with corrugated exterior with few of these slipped and polished over corrugations. Fire-clouding on 20 percent.

Shapes. Bowls, ladles, jars and canteens, and pitchers. Only two squash-pot rim sherds found. Bowls run three to two over jars and canteens, indicating much higher proportion of the latter than in Piedra. Indented jar base and indented strap handle make appearance. The hollow tube ladle handle occurs but the U-shape, half-gourd or wide flat handles are much more common (fig. 40). Rims: 85 percent either rounded or flat and somewhat tapered (fig. 41).

|

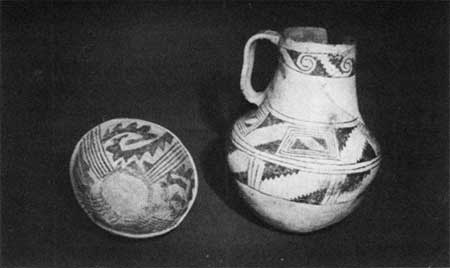

| Figure 40—Bowl and pitcher of Cortez Black-on-white. Chappell collection, Mancos, Colo. (pitcher 0.6' high). |

|

| Figure 41—Cortez Black-on-white rim forms. |

Thickness. Average 5 mm.; range 3-9 mm.

Design. Carried forward from Piedra are groups of vertical or oblique parallel lines from bottom to rim which frequently cross over a narrow subrim band, and often with a series of flags or triangles appended to the outside lines (fig. 42, e—h, l). Most characteristic of the type is the use of ticked or scalloped frets or scrolls employed either singly or interlocked in the Red Mesa style (fig. 42, a, j—l); series of nested rectangles framing a small design element such as a stepped or terraced solid (fig. 42, c); "barbed wire," wavy or zigzag lines (fig. 42, b, d, f, h, i); checkerboard and opposed ticked or scalloped triangles (fig. 42, m—p). Squiggle hachure, usually combined with one or more of the above techniques, appears on Cortez. Straight-line hachure is rare. Hachure, when it occurs, tends to be rather open and at right angles to the framing lines. Eighty-five percent of rims are painted. Paint: Mineral and usually a deep matte black with oxidation on some. (Since this was first written sherds from Badger House, Site 1452, have appeared which seem to be Cortez Black-on-white but with an organic paint.) Exterior decoration of bowls rare.

|

| Figure 42—Cortez Black-on-white sherds. |

Remarks. The considerable variation in tempering material is of interest. The use of sherds as temper, first noted in Cortez, occurred in 30 percent of the 75 sherds inspected under a binocular microscope. Finely crushed rock was also present in most sherd-tempered specimens. Three sherds contained sand in addition to sherd temper; 13 percent were tempered with sand alone. The presence of so many sand-tempered sherds in a type receiving its decorative influence from the sand-tempered Chaco pottery is suggestive. The thick, white, highly polished slip on these specimens would rule out the possibility that they were imported from that area, however. Some sherds bearing Piedra design styles, but none of the elements typical of the new ware, were called Cortez because they bore a corrugated exterior or were heavily slipped and polished on both sides and were found in Pueblo II contexts.

Cortez Black-on-white differs from Mancos Black-on-white chiefly in the element of painted design, but because of an association limited to early Pueblo II traits the separation is useful. Because of its similarity in every other criterion, it might more appropriately be considered a variety of Mancos.

MANCOS BLACK-ON-WHITE

Mancos Black-on-white is the most common decorated pottery of the Mesa Verde area and was probably made for a longer period, with comparatively little change, than any other type since the La Plata Black-on-white of Basketmaker III and early Pueblo I times. It parallels quite closely the Escavada-Puerco-Gallup-Chaco series to the south both in design and in timespan. It is not so useful in dating as other local types because it occurred in the early Pueblo II Ackmen Phase, was common throughout the Pueblo II Mancos Phase, and was the predominant ware on many of the early Pueblo III McElmo Phase sites surveyed on Wetherill, thus spanning the years from about A.D. 950 to 1150.

Gladwin (1934) makes the first use of the name "Mancos Black on White," giving credit to Earl Morris for suggesting the name for the Mancos Phase. The ware was described by Martin (1936) for the first time, and the description has been amplified and redescribed often and well. Morris' (1939) exhaustive analysis of "Early Pueblo III" pottery would be difficult to improve on. The discrepancies in the various descriptions are largely differences of opinion as to where to draw the line dividing one type from another.

I should point out wherein the following description of Mancos Black-on-white from the Wetherill Mesa survey differs from others. Abel (1955) has described a type he calls Morfield Black-on-white, distinguished from Mancos by its rock temper and absence of slip. Both rock temper and unslipped pottery are common in all local types including classic Mesa Verde Black-on-white. Abel's Morfield sherds, available in the park museum, could probably be called either Mancos or Cortez Black-on-white. The bulk of "Morfield" I consider, with Rohn (1959), to be Mancos Black-on-white. Reed (1958), as mentioned above, included Cortez Black-on-white in his description of Mancos. Rohn (1959) has included in Mancos an organic paint variation which I shall treat separately for reasons brought out later.

DESCRIPTION (of 2,600 shreds from 400 sites)

Paste. Light to dark gray. Much like Cortez, well fired with carbon streak in 24 percent. Temper: 44 percent sherd (with varying proportions of crushed rock or sand—more rock than sherd in most specimens), 37 percent crushed rock, 8.5 percent sand.

Surface. Fire-clouding on 8 percent. Ten percent of jars and 13 percent of bowls unslipped but majority of these polished. Most bowls (69 percent) slipped both inside and out. Slip sometimes thin and bluish but usually substantial, clear white and well polished with a fine crackling of the surface. Although unpolished low spots can usually be found, compared with earlier wares or contemporary wares from surrounding areas, Mancos has an excellent surface finish. Corrugated exterior on 4.5 percent of bowls with rare occurrence of coiled or twined basket impression (fig. 63, b).

Shapes. Bowls, ladles (73 percent), short-necked jars, canteens, pitchers, seed jars (fig. 43), and but few sherds that could be from effigy vessels. No mug sherds here but Mancos Black-on-white mugs appear in the Clifford Chappell collection in Mancos, Colo. (fig. 44). The hollow tube ladle handle most numerous but the half-gourd handle still common. Some continuation of the early rounded loop handle on jars but the flat, depressed strap the most common. Handles on bowls occur rarely but observed were round horizontal loop, flat button of applied clay, and small perforated nipple. Rims: 78 percent rounded, 14 percent flat, 4 percent tapered, with no apparent differences between jars and bowls (fig. 45).

|

| Figure 43—Mancos Black-on-white vessels from the Chappell collection. (Bowl on left 0.54' wide). |

|

| Figure 44—Mancos Black-on-white mug. Chappell collection. (0.3' high). |

|

| Figure 45—Mancos Black-on-white rim forms. |

Design. A greater variety of design styles than in the preceding types, reflecting or paralleling most of the Pueblo II styles of the Anasazi and including solid triangles (15 percent), broad-line elements as in Escavada, Puerco, or Sosi (14 percent), checkerboard pattern (9 percent), and hachure between parallel framing lines as in Gallup, Chaco, or Dogoszhi (55 percent) (figs. 46-48). Life forms very rare. Rims usually painted solid (69 percent), sometimes ticked (4 percent). Simple line decoration of bowl exterior still rare (2 percent). Paint: Mineral. Dark gray, sometimes a greenish-gray to black; usually a deep, matte black. Eight sherds in polychrome: two shades of mineral paint.

|

| Figure 46—Mancos Black-on-white sherds. |

|

| Figure 47—Mancos Black-on-white pitcher (cat. #13157/702). From Site 1344. (0.5' high). |

|

| Figure 48—Mancos Black-on-white bowl (#13156/702). From Site 1337. (0.65' high). |

Thickness. Average 4.5 mm.; range 3-7 mm. Jars average slightly less than bowls.

Remarks. The determination of the presence of a slip is not an easy matter when dealing with pottery as highly polished as most Mancos. Occasionally brush strokes indicate that an extra wash of thin clay was added, but more frequently there is no evidence that what appears to be an added coating has not been floated to the surface by excessive polishing of the damp surface. A check of 50 specimens under the microscope revealed the presence of a thin slip on two sherds which had previously been called unslipped. Several sherds which were thought to have been slipped showed in cross section no sharp demarcation between surface and the body of the paste.

In the working out of measurements and percentages, each of the design elements used was studied separately and checked against the sites from which they came to see if significant differences existed. Of the total of 2,600 sherds, 675 could not be typed by design style. In addition to the organization of elements mentioned above under "Design" were the following ones which altogether made up only 7 percent: step-and-terraces, broad-line spirals, dots and the use of repeated groups of parallel short lines of progressive increasing length pendant from the rim (common on small bowls and ladles) (fig. 46, p). Hachured sherds were further broken down into cross hachure (fig. 46, e), straight line hachure (fig. 46, c, d), or squiggle hachure (fig. 46, a, b) Of the three, the cross-hachured sherds were the least common and straight-line hachure the most common, making up over a third of all sherds. Nothing much came of all this except that squiggle hachure appears to be an early trait, straight-line hachure comparatively late. We have already observed the appearance of the squiggles in Cortez and that the majority of Mancos sherds bearing this design element came from early Pueblo II sites. Also of possible significance is that most of the broad-line spirals (fig. 46, m, n.) came from McElmo Phase sites. The most common style of Mancos found on Pueblo III sites was the straight-line hachure. Morris (1939, p. 202) had already found this out for us. Also of interest is the fact that straight-line hachured sherds were predominantly rock tempered whereas all other styles showed a predominance of sherd temper. The majority of ticked rim sherds were found on Pueblo III sites.

As with all other types discussed, there were sherds which could not be classified. Eighty sherds were felt to be in the Cortez-Mancos continuum but were not clearly one or the other and were not considered in the description. Perhaps both types could be better defined; this may be possible after future excavations supply us with more whole vessels. Many of the sherds which have been here considered Mancos could have been from Cortez vessels. Squiggle hachure and checkerboard patterns occur on the latter, but if not combined on the sherds with exclusively Cortez features, they were considered to be Mancos.

WETHERILL BLACK-ON-WHITE

The continuum of types from early to late in the occupation of the Mesa Verde is quite clear. The changes in decorated pottery styles from Mancos Black-on-white to Mesa Verde Black-on-white can be demonstrated to be a gradual and continuous change within the same tradition, but the narrative of this change is difficult because of the confusion in the literature. It is with trepidation and at risk of compounding the confusion that I relate what the transition looks like from a study of the Wetherill Mesa Survey material.

Reed (1958, p. 102) has defined the extent of the problem of McElmo Black-on-white. Most students of Mesa Verde ceramics have recognized the local continuity of types and that in the series between Mancos Black-on-white and Mesa Verde Black-on-white something else occurred which has usually been called McElmo Black-on-white, but descriptions of the type or types vary greatly. At least three fairly distinctive styles or techniques belong in this part of the ceramic history and have been called McElmo Black-on-white, entirely or in part, by someone. They are: (1) what is essentially Mancos Black-on-white in carbon-paint (fig. 49), (2) an often unslipped, primitively decorated pottery with sloppy carbon paint linework (figs. 50, 51), and (3) Kidder's "proto-Mesa Verde" (fig. 52).

|

| Figure 49—Mancos Black-on-white bowl and pitcher in carbon paint, the proposed Wetherill Black-on-white. Chappell collection. |

|

| Figure 50—McElmo Black-on-white bowl (cat. #13147/702), 1.1' wide. Found at Site 1308 with jar in figure 35. |

|

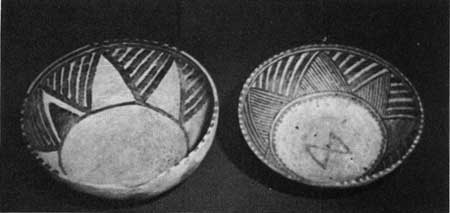

| Figure 51—McElmo Black-on-white jar 0.6' high with remnants of yucca leaf sling (cat. #13182/702). From Site 1433. |

|

| Figure 52—McElmo Black-on-white (proto-Mesa Verde) bowls from the Chappell collection. (Bowl on right is 0.6' wide). |

The first of these forms was treated by Morris, who called what we now know as Mancos Black-on-white, "early Pueblo III Black-on-white." He mentions "the gradual coming-in of the organic black" (Morris, 1939, p. 206) and illustrates several vessels of the ware (ibid., pls. 299-301) which he considers the forerunner of true Mesa Verde. The elements of the designs are Mancos, the arrangement of the elements tends to banding below the bowl rims, and the paint is carbon. It is this style that Wendorf refers to as McElmo Black-on-white, which he describes as having "designs in organic paint in the 'Dogoszhi' and 'Sosi' styles" (Wendorf, 1956, p. 6, figs. 36, 38, 120, 121). O'Bryan lumps all carbon-paint pottery that is not true Mesa Verde Black-on-white into the McElmo category, including that with Mancos design (O'Bryan, 1950, pls. 46, a; 47, a, f, g, i). Rohn's approach to the problem is to consider it an organic-paint variation of Mancos Black-on-white (Rohn, 1959, p. 11). This is reasonable inasmuch as he has further considered Styles 2 and 3 of this transitional pottery to be the McElmo varieties of the type Mesa Verde, and certainly the style in question is closer to Mancos than to Mesa Verde. I agree with the principle of separating this style from McElmo but would go farther.

As the survey material was studied in the laboratory it became more and more obvious that it was this "Mancos" in carbon paint which was associated with the early Pueblo III unit pueblos and with no other phase; whereas Styles 2 and 3, here acknowledged as McElmo Black-on-white, although occurring in varying proportions in large collections from these sites, are also found in greater quantities on late Pueblo III sites. "Carbon-paint variety of Mancos Black-on-white" was an awkward term to use for anything referred to so often; in laboratory notes it was called "type x." I do not like to be responsible for adding to the proliferation of names of pottery; but as I believe it to be more significant than McElmo Black-on-white, I propose to call it Wetherill Black-on-white. If this "kind" of pottery continues to deserve being singled out, it might properly be called the Wetherill variety of Mancos Black-on-white. Table 3 correlates, if I have interpreted them correctly, various systems of Mesa Verde ceramic classification and, in particular, shows how Wetherill Black-on-white fits into the series.

TABLE 3.—Correlation of various systems of Mesa Verde pottery

classification

(click to see copy

of original table in a new window)

| Dates A.D. | 900 | 1000 | 1100 | 1200 | 1300 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Martin | Red Mesa B/W | Mancos B/W (illustrates carbon paint and ticked rim) | McElmo B/W | Mesa Verde B/W | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Morris | Pueblo II B/W | Early P III (mineral paint) |

Early P III (carbon paint) | Mesa Verde B/W | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Abel | Cortez B/W | Mancos and Morfield B/W (no mention of carbon paint) |

McElmo B/W | Mesa Verde B/W | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reed | (admits possibility of separation) Mancos B/W (admits possibility of separation) | Mesa Verde B/W | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rohn | Cortez B/W | Mancos B/W (organic paint variation) | McElmo and Mesa Verde B/W | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hayes | Cortez B/W | Mancos B/W | Wetherill B/W | McElmo and Mesa Verde B/W | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

DESCRIPTION (of 269 sherds)

Paste. Indistinguishable from Mancos Black-on-white. Temper: 60 percent crushed rock, 40 percent sherd. Most sherd-tempered specimens carry more rock than sherd. Carbon streak 20 percent.

Surface. Same as Mancos Black-on-white. Seventy-six percent of bowls slipped and polished on both sides; 6 percent unslipped but polished inside or both sides; 3 percent with corrugated exterior. One sherd each of tooled coil exterior and basket impression. Slip and polish a little heavier than on Mancos average.

Shapes. Same as Mancos Black-on-white. Seventy-four percent were bowls or ladles but possibly many jar sherds were not recognized, as jars in McElmo and Mesa Verde often have very open design and are more primitive-looking than bowls. Rims: 62 percent rounded, 30 percent flat. Flat rims increased over Mancos Black-on-white; these are not the square rims of Mesa Verde Black-on-white but are tapered (fig. 53).

|

| Figure 53—Wetherill Black-on-white rim forms. |

Design. Essentially the same as Mancos Black-on-white, employing same elements as in earlier ware but in carbon paint. Tendency to arrange design in a band under the rim (fig. 54, c—e, j, k) and in a somewhat bolder or more open layout, perhaps necessary because of blurring of painted lines, for new carbon-paint medium not yet mastered. Three sherds of "polychrome" using combinations of mineral and organic paint. One with anthropomorphic figure. Rim ticking increased to 34 percent, unpainted rims to 44 percent. Exterior decoration of bowls even rarer than on Mancos Black-on-white.

|

| Figure 54—Wetherill Black-on-white sherds. |

Thickness. Bowls average 5 mm.; range 4-6 mm. Jars average 4.6 mm.; range 3-6 mm.

Remarks. In this ware we see the first steps in the trail from Mancos Black-on-white to Mesa Verde in the increase in rim ticking and of the flattened rims, a slight increase in thickness of vessel wall, a little more emphasis on surface finish, the beginnings of banded design layout, and, most significant, the jump to carbon paint. It is not the dominant type at any site, but is found in appreciable quantities only on the mesa-top unit pueblos of the McElmo Phase, associated with Mancos Black-on-white and Mancos Corrugated, and rarely with the proto-Mesa Verde style of McElmo Black-on-white. The latter, however, is more common on Mesa Verde Phase sites where Wetherill Black-on-white does not follow.

McELMO BLACK-ON-WHITE

That the transition from Mancos Black-on-white to classical Mesa Verde was not abrupt was first pointed out by Kidder (1924, p. 67, pl. 27, a), who called the pottery from the large unit pueblos of the Four Corners country "proto-Mesa Verde." The pottery he illustrates appears to be the same type that Martin (1936) describes as McElmo Black-on-white, borrowing the name from Gladwin (1934). O'Bryan (1950) and Abel (1955) at least include "proto-Mesa Verde" in their McElmo from Chapin Mesa, although the former illustrates some that I would call classic Mesa Verde Black-on-white. Reed (1958) describes McElmo from his Mancos Canyon Site 1 that would be Kidder's proto-Mesa Verde but recognizes from his collection that he had several varieties that were either McElmo or Mesa Verde but not cohesive enough to type. On Alkali Ridge, in Unit 1 of Site 13, Brew found such variety in the transition from Mancos to Mesa Verde that he was content with the understanding that a large number of the sherds between the two were untypable and that McElmo can safely be called early Mesa Verde (Brew, 1946, pp. 199, 285). The publications dealing with Chaco Canyon also lack agreement on what McElmo is.

Lancaster and Van Cleave (1954, p. 103), in dealing with the pottery from Sun Point Pueblo, thought of McElmo as a style of Mesa Verde rather than a separate type. Some of it certainly is that, but when O'Bryan (1950, p. 99) says, "Undoubtedly, inferior Mesa Verde potters continued to make many McElmo vessels," he is implying that it is sloppy Mesa Verde, which it is not. A vast range of skill is exhibited in every type. Carelessly done Mesa Verde is still Mesa Verde Black-on-white. Rohn (1959) has gone a step farther than Lancaster and Brew and described McElmo not as a type but as a variety of Mesa Verde. Like O'Bryan, Rohn includes in his description of McElmo "very crudely executed Mesa Verde Black-on-white designs as might be done by novices or physically ailing potters." Although I cannot agree with classificatory separation of substandard pots, I do agree that there is logic to the assignment of varietal status to McElmo.

Certainly the differences between McElmo, whatever it is, and Mesa Verde are not as great as those between some of the design styles within the type Mancos Black-on-white. What is described below as McElmo is essentially "proto-Mesa Verde" (fig. 55, k-m) and is Rohn's McElmo, minus the amateur Mesa Verde. It succeeded Wetherill Black-on-white described above, closely preceded classic Mesa Verde, and then continued to be manufactured concurrently with the latter. It is found in small percentages on McElmo Phase surface pueblos associated with Mancos Black-on-white and Wetherill Black-on-white, and also in minor proportions in cliff dwellings where Mesa Verde Black-on-white is the dominant decorated pottery. On only two sites surveyed was it the dominant type.

|

| Figure 55—McElmo Black-on-white sherds. |

After separating Wetherill Black-on-white and eliminating unesthetic Mesa Verde, we are left with a couple of fairly distinctive groups, but unfortunately a number of combinations of Mancos and Mesa Verde still make a catchall of McElmo. This makes a far from satisfactory typology whether McElmo is a "type" or a "variety." I do not consider the style to be diagnostic of the McElmo Phase unless found in some quantity in sites displaying no Mesa Verde, and such sites are rare. In coarse sorting I include it with Mesa Verde Black-on-white.

DESCRIPTION (of 346 sherds)

Paste. Dark gray to almost white. Carbon streak 30 percent. Tends to be somewhat crumbly and softer than Mancos. Fifty-five percent sherd tempered (with much rock included), 45 percent rock tempered. Temper ground finer than in Mancos.

Surface. Twenty-eight percent unslipped but with some degree of polish, most of balance slipped and polished both sides. Slip often thick and heavily polished. Some crazing of surface. Rare bowls are slipped and polished inside but unfinished out.

Shapes. Bowls shallower and with more sloping sides than in Mancos. Ladles with hollow tube, round solid, or strap handles. Half-gourd type diminishing in importance but persisting. Jars, canteens, and mugs. Bird effigies seen in local collections. Reappearance of Piedra-style round loop jar handle. Rims: 55 percent round, 45 percent flat but only one of these squared as in Mesa Verde. Less taper to rims than in Mancos and often none (fig. 56).

|

| Figure 56—McElmo Black-on-white rim forms. |

Design. Primitive Mesa Verde designs consisting of broad line, triangular frets, nested chevrons, often in banded layout under bowl rims (fig. 55). The dark gray, unslipped sherds most often with modified Mancos styles such as closely spaced lines framing rows of ticks or dots, checkerboard pattern with dots in the white squares. Paint organic and often runny or blurred. Mineral paint on rare specimens. No polychromes in survey sherds. Sixty-seven percent of rims ticked. Also occurring are Mancos designs on thick-walled, untapered-rim bowls and Mesa Verde designs on thin-walled, tapered- and rounded-rim vessels. No exterior decoration noted.

Thickness. Bowls average 5.5 mm.; range 4.5-7 mm. Jars average 5.6 mm.; range 4-8 mm.

Remarks. Typical of the range of pottery in McElmo Phase site are the 83 decorated sherds picked up at Site 1801, a small unit pueblo on the ridge east of Bobcat Canyon. Twenty-seven of these were Mancos Black-on-white decorated with mineral paint. Eight were Wetherill Black-on-white, Mancos design in organic paint. Twenty-one sherds were typed as McElmo Black-on-white constituting a higher percentage of this type than is usual. Five were thin walled and with tapered rims, and one was Mancos in design but Mesa Verde in thickness of paste and in approach to design layout. Fourteen sherds could not be ascribed to any variety or type but belonged in the continuum. Thus 43 of the 83 sherds were neither Mancos nor Mesa Verde. The site seems to have been occupied for a comparatively short time in the Mancos Phase, not at all in the Mesa Verde Phase. There is little question what era the site represents and no indication that any of the pottery is exotic. If we were to lump all the pottery decorated with carbon paint from this site into McElmo Black-on-white, we might be guilty of a rather loose-jointed use of taxonomy but we would be describing the pottery of a spatially and temporally compact phase.

Rohn has assigned the later styles of McElmo a varietal status under the type Mesa Verde Black-on-white; some of McElmo has become the carbon-paint, or Wetherill, variety of Mancos. We have thus eliminated the type, but whether the problem of McElmo has been eliminated will have to be proved by the spade. We can hope the excavations on Wetherill will help.

MESA VERDE BLACK-ON-WHITE

DESCRIPTION (1,059 sherds)

Paste. Gray to white. Tends to be softer than Mancos and crumbly. Averages 2.5 on hardness scale, contrasted to 4.9 for Mancos. Temper: 26 percent crushed rock (combined with sand or sandstone in 2 percent), 72 percent sherds (combined with sand or sandstone in 14 percent), 2 percent sand. The sand or sandstone in many sherds could be result of grinding temper on sandstone metates. Carbon streak 24 percent.

Surface. Eighty percent of bowls slipped and polished both sides, 14 percent with self-slip or float in and out, 2 percent unslipped. Surface, whether slip or float, usually heavy or opaque, gray through cream to clear white, frequently with fine crackling, polish frequently a high luster with appearance of a glaze. Slip harder than paste (3.7). Corrugated exterior very rare.

Shapes. Bowls, ladles, jars, canteens, mugs (figs. 57-59). Pitchers and effigies seen in private collections from vicinity. Jars globular with high shoulders and narrow mouth, short necks often corrugated. Kiva jars with pottery lids; seed jars rare. Jar handles round, or undepressed flat straps, below shoulder of vessel. Ladle handles hollow tube, round or flat, none of the half-gourd type seen. One narrow troughlike handle. Rims: 94 percent untapered and flat, usually squared. Jar rims slightly flared. The bowl rim sloped from the inside or slightly flared is rare, between 1 and 2 percent (fig. 60).

|

| Figure 57—Mesa Verde Black-on-white bowl (cat. #12043/702), 0.96' high. From Site 1365. |

|

| Figure 58—Mesa Verde Black-on-white jar (cat. #12043/702), 0.92' high. From Site 1187. |

|

| Figure 59—Mesa Verde Black-on-white mugs from ruins near Cortez, Colo. Mug on extreme left is in mineral paint. Chappell collection. |

|

| Figure 60—Mesa Verde Black-on-white rim forms. |