|

MESA VERDE

The Archeological Survey of Wetherill Mesa Mesa Verde National Park—Colorado |

|

THE ARCHEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF WETHERILL MESA (continued)

conservation of soil and water

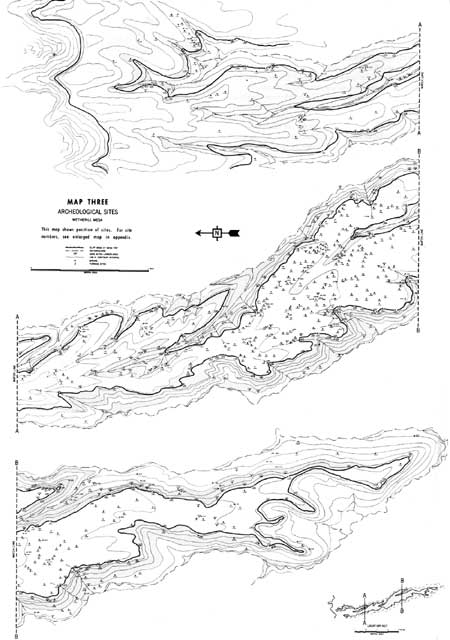

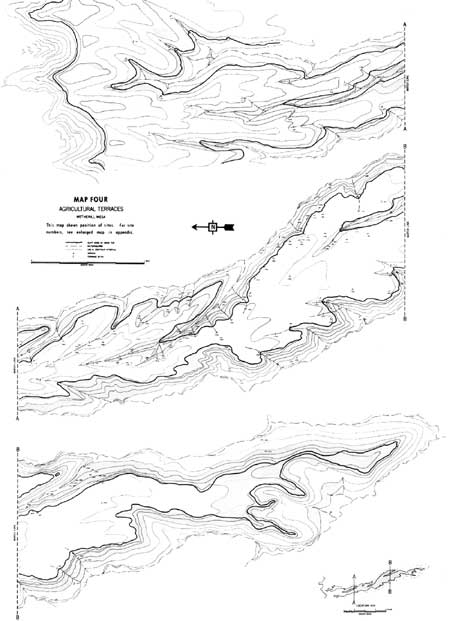

Construction for the purpose of conserving soil and moisture on Wetherill Mesa is of two general types. First are tanks or reservoirs for the impounding of domestic water, and second, low terraces to catch eroding soil and to slow the runoff. The latter can be further subdivided into check dams built across arroyos where water is channeled (fig. 64), and terraces following the contour of a slope where runoff is sheeted (fig. 65). The few definite storage tanks on Mesa Verde will be dealt with later. Soil-holding terraces are numerous. Sites including one or more such terraces numbered 136 with an estimated 943 individual terrace walls. Many more must have been washed away (map 4).

|

| Figure 64—Four of a series of 10 check dams in the drainage of Rock Springs Canyon. Site 1485. |

|

| Figure 65—One of four terraces on the talus slope in Long Canyon. This one is 15 feet long, 2 feet high, and holds considerable soil. Site 1361. |

Nordenskiold (1893) noted and illustrated terraces on Mesa Verde and speculated on the possibility of their use for farming plots. Stewart (1943) made a more detailed description of some of the extensive check-dam sites on the mesa. Remarkably similar developments are described for the Point of Pines area in southeastern Arizona by Woodbury (1961), who uses the terms "terraces" and "linear border" for "check dam" and "contour terrace" as they are used here. The latter two terms are in common use in present-day soil conservation practice to denote two types of terraces, whereas the term "border" has a somewhat different meaning in current irrigation farming.

Of the 136 sites surveyed, only 71, containing 412 individual terraces, were on the mesa top. A few of these were long contour terraces on the slopes just above the top of the cliff, but the majority were check dams located in shallow arroyos near the cliff edge. With the exception of a very few in the bottoms of the main canyons, the rest of the terraces were found on talus slopes between the base of the lower bluffs and canyon bottoms. On the talus locations check dams were most numerous, but contour terraces common.

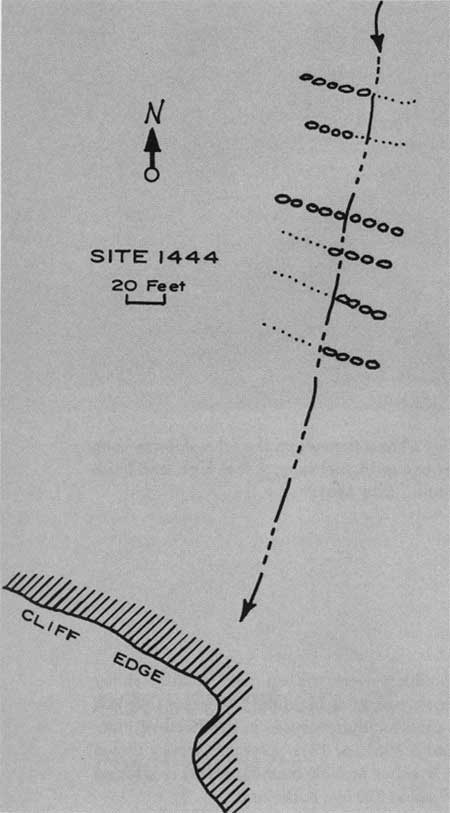

Typical mesa-top check dams occur at Site 1444 near the cliff edge above Kodak House (fig. 66). Here bedrock is exposed in an arroyo for 200 feet back from the pouroff at the edge of the mesa. Six terraces built across the wash above this point have collected soil to the depth of 3 feet. Subsequent washing has partially destroyed five of the six checks but the remaining portions of those still hold soil. One, still complete, is 50 feet long and holds a depth of 3.5 feet of soil. The ends of the unbroken terrace are buried in the banks of the arroyo. The grade is gentle, with an average of 21.6 feet between walls. The masonry, of large unshaped stones, is based on bedrock. The considerable amount of soil retained for better than six centuries by these check dams is a testament to their value. Since it is unlikely that the builders placed them in a trench, the arroyo bottom must have been bare rock at the time of their construction.

|

| Figure 66—Sketch map of a series of check dams at Site 1444, near Kodak House. |

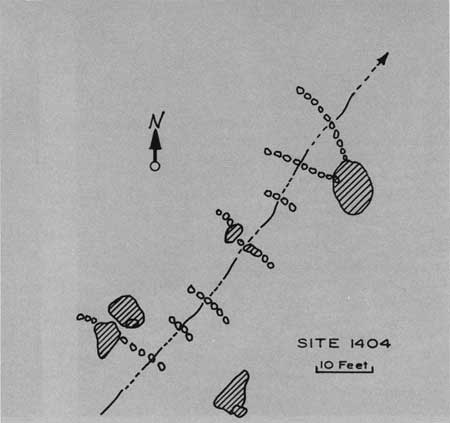

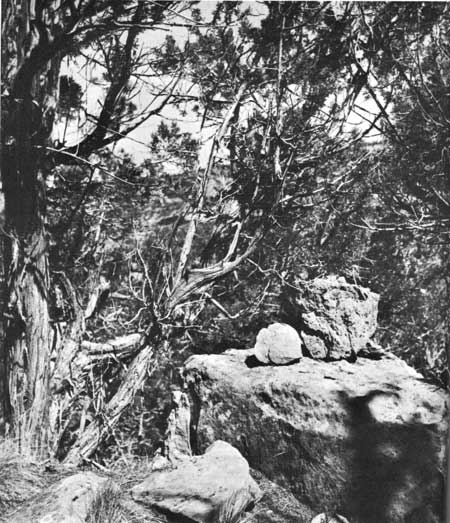

Eight check dams in a series at Site 1404, on the talus slope at the mouth of Bobcat Canyon, are on steeper ground and are placed closer together, averaging 8.7 feet between checks (fig. 67). They vary in width from 6 to 20 feet, with a maximum wall height of 3 feet. Large colluvial sandstone boulders were used by the builders as abutments for several of the check dams, and other large stones were incorporated in the walls. Three of these large boulders were topped with smaller stones which may have served as boundary markers, like the upright slabs used for that purpose in the Point of Pines area (Woodbury, 1961, p. 13). One of these is shown in figure 68. Another possible boundary marker is found near Site 1399 about 200 feet to the south.

|

| Figure 67—Sketch map of agricultural terrace on the talus in Bobcat Canyon. Site 1404. |

|

| Figure 68—Possible boundary-marking stones. Site 1404. |

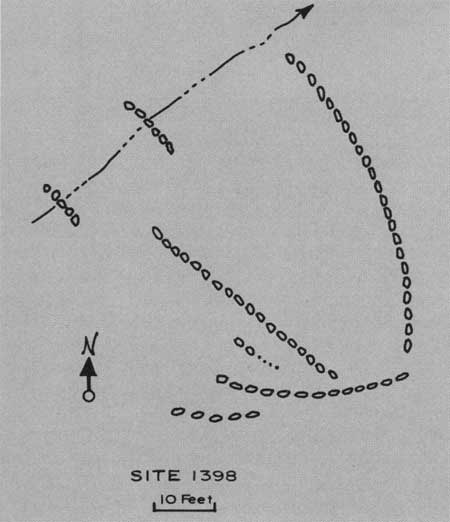

Not far from Site 1404 is a terrace complex combining check dams and contour terraces. Site 1398 (fig. 69) consists of two check dams and two contour terraces 42 and 53 feet long. The latter probably carried overflow water from the shallow arroyo and spread it onto the relatively level bench to the south. The two walls running east and west to the south of the contour terraces are built against the base of a steep bank, and prevent alluvium from washing onto the farm plots, but allow water to be kicked back to the west above the upper terrace. A similar system of water control is described by Cushing (1920, p. 156) at modern Zuni Pueblo.

|

| Figure 69—Sketch map of check dams and contour terraces on the talus in Bobcat Canyon. |

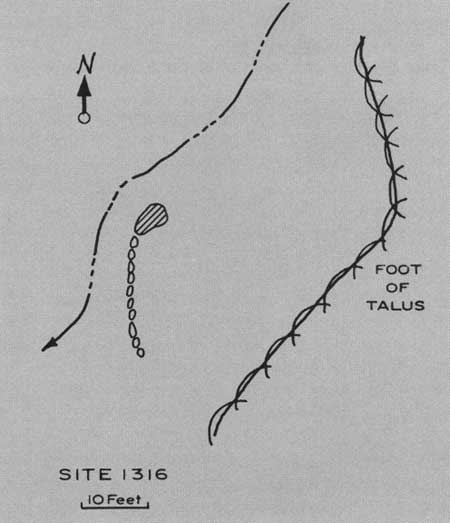

A true terrace is Site 1316 in Rock Canyon near the mouth of the rincon below Long House. Here an unbroken wall 5 feet high and 16 feet long is butted on a large fallen boulder some 20 feet in front of the foot of the talus. An artificial bench, 40 by 30 feet, was created of rather level alluvial soil (fig. 70).

|

| Figure 70—Sketch map of large terrace near confluence of Long House draw with Rock Canyon. Site 1316. |

On the steep, brushy talus slope in Long Canyon south of Step House is Site 1297, where a group of an estimated number of 100 terraces from 6 to 15 feet long runs for a quarter of a mile from north to south. This section of the talus was surveyed by 8 men abreast, at an interval of 25-30 feet, who counted a total of 60 individual terraces. Because of the dense brush and limited visibility we felt we had probably missed half the structures. This area represents the largest concentration of terraces found. Most are built across small watercourses but many of the check dams are connected, from one small arroyo to the next, by long contour terraces on the unchanneled slope.

Another large area of intensive development is Site 1539, which is placed in a short, steep tributary from the west into Rock Springs Canyon. A series of 25 check dams extend for 500 feet from near the foot of the cliff to the bottom of the main canyon. At their southern ends many of the checks are connected to contour terraces running along the foot of the steep hillside to the south (fig. 71). Two smaller arroyos coming off this steep hill are also equipped with a dozen or more check dams. A 300-foot stretch of hillside between the two smaller arroyos is covered with numerous lateral terraces on the contour, which thus made cultivatable an area of about 3 acres. Some testing with the shovel at a couple of the check dams indicates that the work in the large arroyo was not so much soil conservation as actually soil building. The check shown in figure 72 as a terrace 8 inches high was excavated to reveal almost 6 feet of wall built on bedrock. Three, perhaps four, stages of building are represented, for the terrace wall is battered and leans toward the uphill slope in such a way that it could not have stood if built to its full height at one time. When the area upstream above the wall was silted in, the wall was raised a few courses in order to trap still more soil and enlarge the catchment area. Profiles show several strata of water-laid soil with no evidence that any had been carried in by hand. A few sherds were found in the fill, with one Cortez Black-on-white sherd at the lowest level. It had probably washed from Site 1540, a Pueblo II site of 10 scattered rooms and many terraces built on a talus bench at the top of the hill to the south of the arroyo. It is probable that Sites 1539 and 1540 are parts of a single complex.

|

| Figure 71—Exploratory pits exposing two sections of a check dam running from large exposed rock at the bottom of the photo to the steep talus near the top. Site 1539. |

|

| Figure 72—One of a series of 25 check dams. Site 1539. |

Still in place at Site 1539 are many yards of soil collected as a result of the building of the terraces—soil that, at least in the arroyo, was not there prior to the building. More work is planned at the site.

At several locations on Wetherill Mesa, under cliffs at a pouroff or at seeps, a little scattered rock was found which suggested that walls had been built for the purpose of catching domestic water. At only one place, Site 1586, was evidence sufficient for proof. The site, at the foot of the cliff at the head of a small rincon a few hundred feet south of Mug House, probably served as a principal water supply for that pueblo. A battered wall 10 feet high forms a basin, about 10 by 25 feet, which caught water coming over the pouroff and from the talus at either side. The reservoir was excavated in the summer of 1961 and will be reported fully with the account of the Mug House excavations.

Two tanks similar in structure to Mummy Lake on Chapin Mesa (Nordenskiold, 1893; Stewart, 1940) were found, neither on Wetherill Mesa but on small unnamed ridges between Wetherill and Chapin Mesas. Site 1669 is on a narrow ridge between the two upper tributaries to the West Fork of Navajo Canyon. It is a U-shaped earthen bank 2 feet high, lined with masonry of finished rock, and encloses an area measuring 27 by 40 feet. The open end faces up the slope of the ridge to the northeast and with the help of shallow lateral ditches could have trapped runoff from an area of about 2 acres. The soil on the ridge both above and below the tank is shallow and rocky and not well suited to farming. Several small Pueblo II and III sites nearby may have used the water stored for domestic purposes.

On a longer ridge immediately to the east, that between the West and East Forks of Navajo Canyon, is a similar reservoir, smaller in area but deeper. The site was investigated in a snowstorm and is not yet surveyed.

The capacity of these tanks, and of Mummy Lake, is not great enough to have provided a sufficient head of water to be of much use for ditch irrigation. There is no indication of an outlet from either of the two lying between Wetherill and Chapin Mesas and, through testing, Rohn has determined that none existed at Mummy Lake (Rohn, 1963). It is probable that domestic water supply was their primary purpose.

The use of large blocks of scabbled or rough stone in house construction was developed in the Mancos Phase, and we can presume that it did not occur earlier in the construction of check dams. The type of masonry coupled with the fact of increased use of the talus slopes as habitation sites during the period, and the proximity of agricultural terraces to most of those sites, strongly suggest that first construction of terraces was late in the 10th or early in the 11th century. The evidence of several rebuilding periods at Site 1539 would further indicate that the use of terraces was continuous, probably until the abandonment of the area.

|

| Terrace in Long Canyon. Site 1361. |

|

| MAP THREE |

|

| MAP FOUR |

|

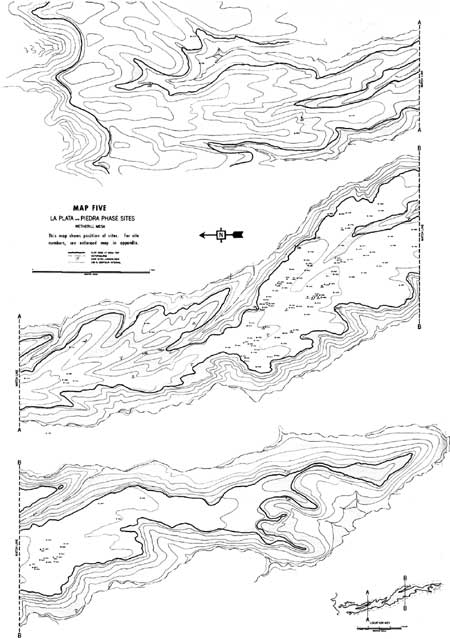

| MAP FIVE |

|

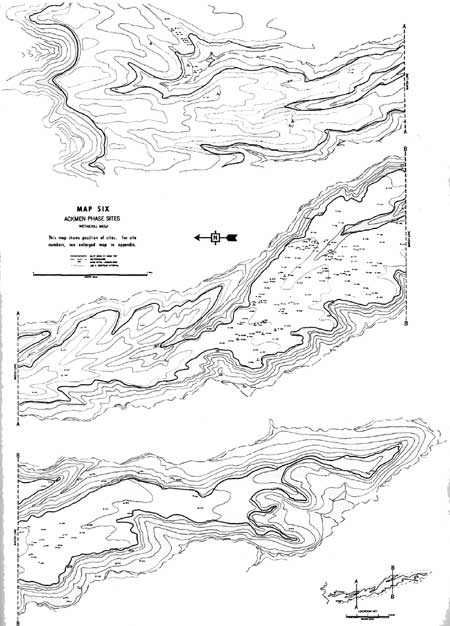

| MAP SIX |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

archeology/7a/survey5.htm

Last Updated: 16-Jan-2007