|

Yorktown Battlefield Part of Colonial National Historical Park Virginia |

|

NPS photo | |

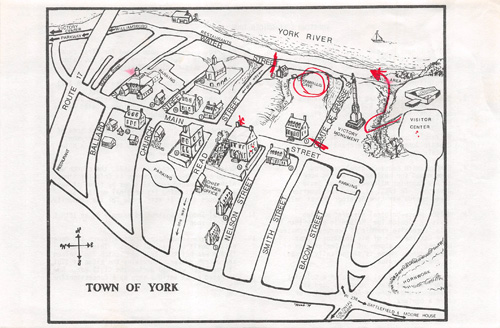

The Town of York

The soldiers who gathered at Yorktown in the late summer and early fall of 1781 to fight the last major battle of the American Revolution knew little about the town's history. It had been established in 1691 by an Act for Ports passed by the Virginia House of Burgesses. This legislation provided for the creation of several port towns, through which all trade goods were to pass and where customs were to be paid. In laying out Yorktown, 50 acres of land were purchased from Benjamin Read next to the York River and the town was surveyed in to 85 half-acre lots.

By the early 1700s the town was a major port serving Williamsburg, the new capital of Virginia. The waterfront was full of wharfs, docks, storehouses, and businesses. On the streets above the waterfront, stately homes of the wealthy merchants lined Main Street, with taverns and other shops scattered through the town. In 1697 the first county courthouse and Grace Church were constructed. Yorktown had become a crowded town, with 200-250 buildings.

Yorktown reached its peak in the 1750s, when there was a population of about 1,800. Tobacco, which had fueled the trade system and was the basis for much of the town's wealth, had exhausted the soil of nearby plantations. Planters began moving westward in search of fertile land. Prominent families, however, such as the Digges, the Nelsons, and the Amblers, who would play important roles in Virginia during the Revolutionary War, still remained. The siege of 1781 destroyed so much of the town that, by the end of the Revolutionary War, the number of buildings had been reduced to fewer than 70. The 1790 census listed 661 residents.

While some rebuilding took place after the war, Yorktown never regained its economic prominence. A disastrous fire in 1814 destroyed the waterfront district as well as some homes and the courthouse on Main Street. During the Civil War, Confederate and then Union forces held the town. During the Union occupation, the courthouse (this one built in 1818) and Swan Tavern served as powder magazines. In 1863 a fire broke out in a nearby hospital bakery and spread to the magazines. The resulting explosions destroyed the west end of town. Though smaller today than during colonial times, the town continues to function as an active community. Several houses and other structures from the colonial period are still standing and give the town much of the character of a long-vanished era. The best way to understand Yorktown is by walking its streets. Please be aware that some buildings are private residences and not open to the public.

The Siege of Yorktown

In the spring of 1781 the American War of Independence entered its seventh year. Having practically abandoned their efforts to reconquer the northern states, the British still had hopes of subjugating the South. By trying to do so, they unwittingly set in motion a train of events that would give independence to their colonies and change the history of the world.

In May 1781 British Gen. Charles, Lord Cornwallis moved his army into Virginia from North Carolina after an arduous and costly southern campaign. He believed that if Virginia could be subdued the states south of it would readily return to British allegiance. In June he received instructions from Sir Henry Clinton, his superior officer in New York, to establish a naval base somewhere in the lower Chesapeake Bay area. The Marquis de Lafayette, operating with a small American force, shadowed Cornwallis's movements and clashed with his army near Jamestown in the Battle of Green Spring on July 6. After the Americans withdrew, Cornwallis continued toward the bay and, on the advice of his engineers, chose the port of Yorktown for his base. Early in August he transferred his army there and began to fortify the town and Gloucester Point across the York River.

Meanwhile, a large French fleet under Adm. François Joseph Paul, Comte de Grasse, had sailed up from the West Indies for combined operations with the allied French and American armies and proceeded to blockade the mouth of Chesapeake Bay, cutting off Cornwallis from help or escape by sea. At the same time, Gen. George Washington began moving the Allied Army, consisting of his own forces near New York City and a French army under Gen. Jean Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, Comte de Rochambeau, in Rhode Island, toward Virginia to attack Cornwallis by land.

Following his victory over Adm. Thomas Graves and the British fleet in the Battle of the Capes on September 5, de Grasse maintained a strict blockade by sea while the Allied army, numbering over 17,000 men, gathered at Williamsburg.

On September 28 they marched to Yorktown to face Cornwallis's 8,300-man garrison. After a week of laying out camps and preparing for a siege, the Allied army constructed its first siege line on October 6 and three days later commenced bombarding the British positions.

After capturing British redoubts 9 and 10 on the night of October 14, a second siege line, designed to bring the Allied artillery to within point blank range, was completed the morning of October 17. That same day, after nine days of intense, round-the-clock bombardment that wrecked the town, and a failed attempt to escape across the York River, Cornwallis requested a cease-fire to discuss surrender terms. Two days later, on October 19, 1781, he formally surrendered his army. When Lord North, the British prime minister, learned of Cornwallis's defeat, he is reported to have cried, "Oh God! It is all over!"

The American victory at Yorktown, the last major battle of the American Revolution, secured independence for the United States and significantly changed the course of world history. After the British surrender, the French forces remained in the Yorktown area during the winter while Washington and most of the American troops, expecting the war to continue, returned to New York. In the summer of 1782 General Rochambeau and his troops departed for New England and left for France in December. Washington kept the American army intact for two more years, until the Treaty of Paris officially ended hostilities in September 1783.

Thomas Nelson Jr., Esq.

Yorktown's most ardent patriot was Thomas Nelson Jr., who led the local "tea party" and tossed tea off a merchant ship in Yorktown harbor in November 1774. He was born December 26, 1738, in Yorktown, scion of a family prominent in colonial Virginia society. After completing his education in England, Nelson joined his father's mercantile business and married Lucy Grymes, with whom he had 11 children. From 1761 to 1775, Nelson served in the Virginia House of Burgesses and then two years as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, where he signed the Declaration of Independence. In June 1781, he was elected the third governor of Virginia, succeeding Thomas Jefferson, and, with the rank of brigadier general, commanded the Virginia militia at the siege of Yorktown. Shortly after Cornwallis's surrender, ill-health forced Nelson to resign as governor. He died on January 4, 1789. Today his house, built in 1730 by his grandfather Thomas Nelson, "the immigrant," still bears the scars from the artillery bombardment during the siege.

The Second Siege of Yorktown

Yorktown came under siege again in the spring of 1862 when Union Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan began his Peninsula Campaign to capture Richmond. Confederate Maj. Gen. John B. Magruder, who had refortified and extended the remains of the 1781 British defense line around the town, was ordered to contain the Federals until reinforcements arrived. He deployed his small force in a way that made it appear much larger. Convinced he was greatly outnumbered, McClellan planned for a siege and called up more men, siege guns, and mortars. He even sent Prof. Thaddeus Lowe and Brig. Gen. Fitz-John Porter up in observation balloons to survey Magruder's position, the first aerial flights ever made over an enemy's defenses. In mid-April Confederate Gen. Joseph E. Johnston brought reinforcements, but the siege dragged on another two weeks. On the night of May 3-4, 1862, two days before McClellan's grand bombardment of the Confederate lines was to begin, Johnston opened an intense artillery fire on the Union position to mask the withdrawal of his forces from Yorktown. As a Union garrison, Yorktown served for the next two years as military headquarters for the Federal-held district of Eastern Virginia.

Touring Yorktown Battlefield

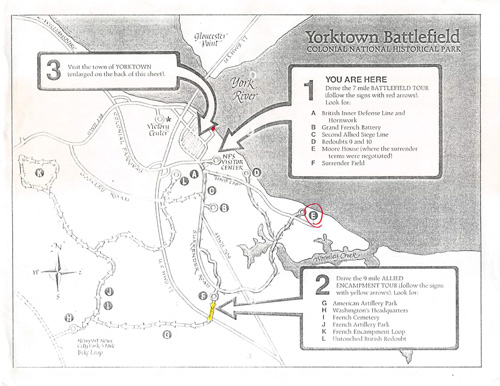

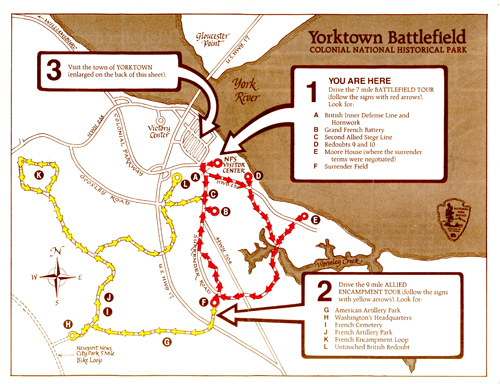

(click for larger map) |

Yorktown Battlefield is a part of Colonial National Historical Park, which also includes Jamestown and Colonial Parkway, connecting sites marking the beginning and end of British colonial experience in America. The park entrance fee is payable at the Yorktown Visitor Center, where events of the siege and the story of the Town of York are recounted in a theater program and exhibits.

Two separate auto tours give you the complete story of events at Yorktown: the Battlefield Tour (Stops A to F) and the Allied Encampment Tour (Stops G to L). We encourage you to take both tours.

Remember: Portions of the park tour roads are heavily traveled major thoroughfares. Be alert for slow-moving traffic, busy intersections, stop signs, joggers, and cyclists. Also, please help us preserve the earthworks on the battlefield. They are important historic resources that help us understand both the Revolutionary War and the Civil War. Do not climb or walk on them, for they are subject to erosion and can be easily damaged; use only authorized trails.

Battlefield Tour is a seven-mile drive covering the British Inner Defense Line, the Allied siege lines, the Moore House, and Surrender Field. Allow at least 45 minutes for this tour.

A British Inner Defense Line After Washington and Rochambeau's allied armies arrived, Cornwallis withdrew his troops from most of his outer defenses to consolidate his position behind these earthworks.

B Grand French Battery During the night of October 6, under cover of darkness and rain, Allied troops constructed the first siege line from this point eastward to the York River. On October 9, Allied artillery opened fire on the British, and the bombardment began. The Grand French Battery was the largest gun emplacement on the first siege line.

C Second Allied Siege Line On October 11, Allied troops began this second line within point blank artillery range of the British. The line could not be completed, however, because two small, detached British earthen forts. Redoubts 9 and 10, blocked the way to the river.

D Redoubts 9 and 10 On the night of October 14, French troops attacked Redoubt 9 while American troops stormed Redoubt 10, capturing both positions in less than 30 minutes. This allowed the Allies to complete their second siege line and construct a Grand American Battery for siege artillery between the two redoubts. Three days later, Cornwallis proposed a cease-fire.

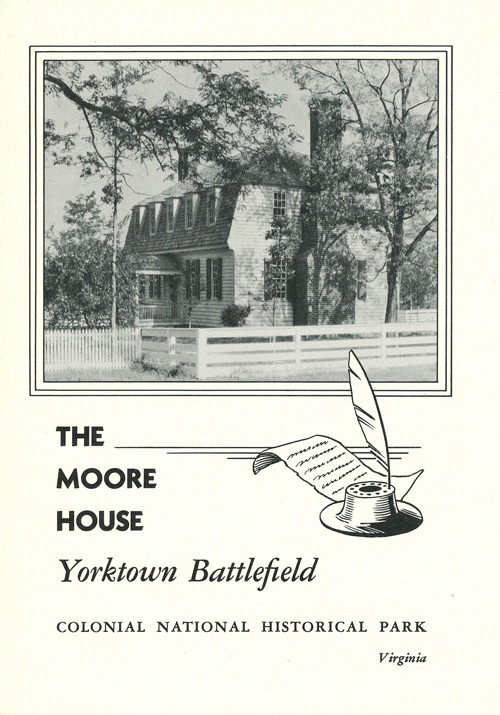

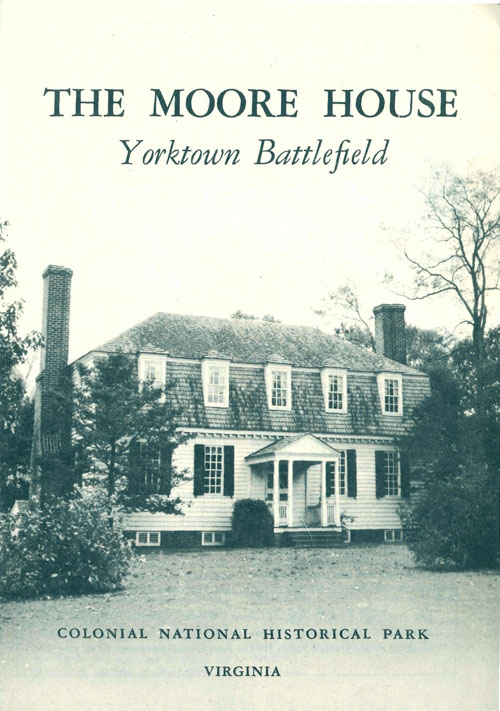

E Moore House On October 18, 1781, officers from both sides met at the home of Augustine Moore to negotiate the surrender terms for Cornwallis's army. Open seasonally.

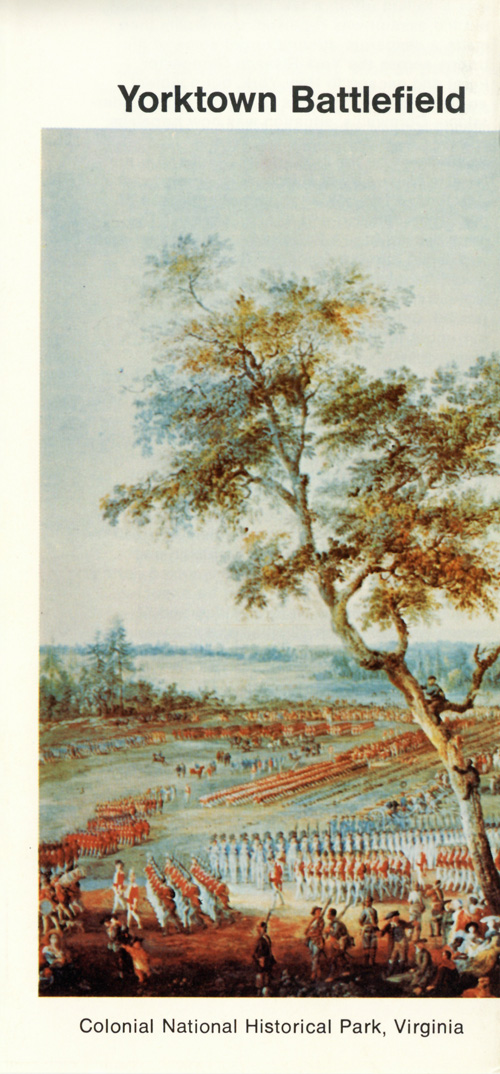

F Surrender Field On October 19, 1781, Cornwallis's army marched onto this field and laid down its arms. This ended the last major battle of the Revolutionary War and virtually assured American independence.

Allied Encampment Tour begins at Surrender Field and takes you on a nine-mile drive through the American and French encampment areas. Allow at least 45 minutes for this tour.

G American Artillery Park In 1781 this scenic area contained Washington's heavy siege guns, carriages and limbers to carry them, and the powder carts and ammunition wagons for their service.

H General Washington's Headquarters As Allied commander, Washington positioned his headquarters between the American and French camps.

I French Cemetery Located several hundred yards south of the French artillery park, this cemetery (according to tradition) contains the remains of approximately 50 unknown French soldiers.

J French Artillery Park This area, arranged similar to the American artillery park, contained the heavy siege ordnance used by the French.

K French Encampment Area Many of the French troops were encamped here on the extreme left of the Allied line. Their commander, Comte de Rochambeau, maintained his headquarters near Washington's.

L Untouched Redoubt This was one of the original detached works on the British outer defense line, abandoned by Cornwallis on September 29, 1781, one day after the arrival of the Allied armies.

Echoes from the Past: Yorktown by Foot (Town Map)

Follow the walkway from the visitor center to see these points of interest:

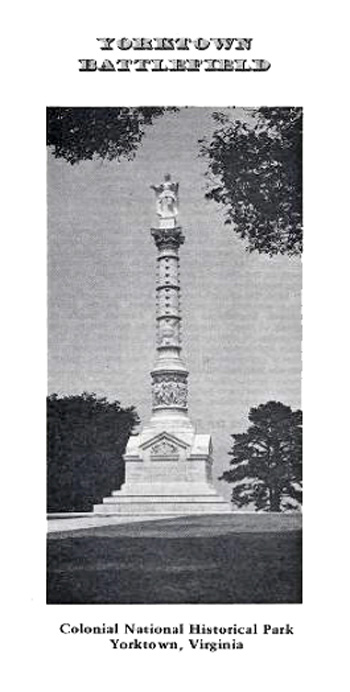

Yorktown Victory Monument Authorized in 1781, construction did not begin until the 1881 centennial of the surrender.

Dudley Digges House* Built ca. 1760 by Digges, a lawyer and Virginia government official, 1752-81.

Sessions House* Built in 1760, was home to merchant John Norton.

Nelson House The Nelson House, on the southwest corner of Main and Nelson streets, is considered one of the finest examples of early Georgian architecture in Virginia. The Marquis de Lafayette, whose tactical skill helped to defeat Cornwallis, was entertained here during his triumphal 1824 United States tour. The house is open daily in summer. Check at the visitor center for other times of the year.

Smith House* Home of Lt. Gov. David Jameson at the time of the 1781 siege.

Ballard House* Restored 1720 home of merchant sea captain John Ballard.

Cole Digges House* Built about 1720, was home of Cole Digges.

Customhouse Built about 1721 by Richard Ambler and used as his office while he served as collector of customs.

Poor Potter Site of the largest known colonial pottery factory, established about 1720. Open seasonally.

Somerwell House* Restored brick home of Mungo Somerwell, a Yorktown ferryman.

Grace Church Built about 1697, this still-active church served the York-Hampton Parish in colonial times.

Swan Tavern* Reconstructed tavern and dependencies built on original 1722 sites.

Medical Shop* Reconstructed 18th-century medical shop of Dr. Corbin Griffin.

Archer Cottage* Typical colonial waterfront dwelling.

*Not open to visitors

*NPS Concessioner

Source: NPS Brochure (2016)

|

Establishment

Colonial National Historical Park — June 5, 1936 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Brochures ◆ Site Bulletins ◆ Trading Cards

Documents

A Completion Furnishing Plan for the Moore House in the Yorktown Battlefield Area of Colonial NHP / Furnishings of the Moore House (Charles E. Hatch, Jr. and J. Paul Hudson, August 1, 1958/January 22, 1959; Charles W. Porter, October 6, 1937)

A Prospectus for the Interpretation of Yorktown Battlefield, Colonial National Historical Park (Nan V. Rickey, 1970)

A Yorktown Surrender Flag — Symbolic Object (James W. Lowry, 1989)

An Old Wharf at Yorktown, Virginia (Charles E. Hatch, Jr. extract from William and Mary College Quarterly, Vol. 22, Second Series, July 1942)

Architectural Analysis of the Nelson House, Colonial National Historical Park, Yorktown, Virginia (Mark R. Wenger and Willie Graham, 2012)

Cole Digges House: A Historic Structure Report (Edward A. Chappell, July 2003, rev. June 2004)

Cultural Landscape Assessment for the Ferris Property, Colonial National Historical Park, Yorktown, VA (Cheryl A. Sams, 2001)

Cultural Landscape Report: Nelson House Grounds, Colonial National Historical Park Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation (Bryne D. Riley, John Auwaerter and Paul Fritz, 2011)

Dependencies (Outbuildings) of the Dudley Digges House in Yorktown, Virginia, Colonial National Historical Park (Charles E. Hatch, Jr., April 1969)

Drawings Illustrating Field Fortifications of Revolutionary War Period (Thor Borressen, 1938)

Furnishing Plan for the Nelson House of the Colonial National Historical Park, Yorktown, Virginia (Lavinia DeNood, 1976)

Grace Church: General Study (Charles E. Hatch, Jr., May 1970)

Grace (York) Church, 1697-1957: A Brief Account of its History (Charles E. Hatch, Jr., July 15, 1958)

Historic Furnishings Report: The Moore House, Colonial National Historical Park, Yorktown, Virginia (Katherine B. Menz, 1985)

Historic Resource Study: Yorktown's Main Street, Colonial National Historical Park (HTML edition) (Charles E. Hatch, Jr., March 1974)

Historic Resource Study: The British Defenses of Yorktown, 1781 (Erwin N. Thompson, September 1976)

Historic Resource Study and Historic Structure Report: The Allies at Yorktown: A Bicentennial History of the Siege of 1781 (Jerome A. Greene, November 1976)

Historic Structures Report, Architectural Data Section: The Ballard House, Yorktown, Virginia (William F. Degler, May 1972)

Historic Structures Report, Architectural Data Section: Restoration of the Archer House, Yorktown, Virginia — Part III (Lee H. Nelson, November 1960)

Historic Structures Report, Architectural Data: Restoration of the Dudley Digges House, Colonial National Historical Park, Yorktown, Virginia — Part II (Lee H. Nelson, May 1960)

Historic Structures Report: The Moore House — The Site of the Surrender — Yorktown (Charles E. Peterson, NPCA Publication, c1981)

Historical Overview of Africans and African Americans in Yorktown, at the Moore House, and on Battlefield Property, 1635-1867, Colonial National Historical Park (Julie Richter and Jody Allen, 2012)

October Nineteenth, Seventeen Eighty-one: Victory at Yorktown: The Story of the Last Campaign of the American Revolution (Joseph P. Cullen, 1976)

Preliminary Report on the Physical History of Yorktown, 1691-1800 (Edward M. Riley, 1940)

Report on American Guns and Carriages (Thor Borresen, December 1939)

Report on the Naval History of the Seige of Yorktown, 1781 (Theodore Edward Temple, November 5, 1937)

Report on the Restoration of the Lightfoot House, Colonial NHP (Clyde Trudell and Raymond A. Wilhelm November 23, 1937)

The "Archer Cottage": An Architectural Survey Report, Colonial National Historical Park, Yorktown, Virginia (George F. Bennett, June 2, 1958)

The Ballard House and Family, Colonial National Historical Park, Yorktown, Virginia (Charles E. Hatch, Jr., September 1969)

The Colonial Courthouses of York County, Virginia (Edward M. Riley, August 18, 1942)

The Edmund Smith House: A History, Colonial National Historical Park (Charles E. Hatch, Jr., August 1969)

The Edmund Smith House: A History, Colonial National Historic Park (Charles E. Hatch, Jr., August 1969)

The Glory of Old Cannon (Thor Borresen, June 12, 1939)

The History of the Founding and Development of Yorktown, VA., 1691-1781 (Edward M. Riley, March 20, 1942)

The Lightfoot Family in Yorktown (Barbara A. Sorrill, May 1964)

The Nelson Family (A Synopsis) (Jerome Fortner, 1967)

The Nelson House and The Nelson: General Study, Colonial National Historical Park (Charles E. Hatch, Jr., August 1969)

The Physical History of the Moore House, 1930-1934 (Charles E. Peterson, 1935)

The West House Property in Yorktown: A Preliminary Historical Statement (W.R. Sampson, April 9, 1956)

Trade and Shipping in Yorktown Before the Revolution (James O'Mara, 1988)

Use Study of the Historic Buildings in Yorktown (Virginia Sutton Harrington, March 2, 1939)

Yorktown and the Siege of 1781: Historic Handbook #14 (Charles E. Hatch, Jr., 1954 rev. 1957)

Yorktown: Climax of the Revolution NPS Source Book Series No. 1 (Charles E. Hatch, Jr. and Thomas M. Pitkin, eds., 1941)

Yorktown: Climax of the Revolution (HTML edition) NPS Source Book Series No. 1 (Charles E. Hatch, Jr. and Thomas M. Pitkin, eds., 1941, reprint 1956)

Books

york/index.htm

Last Updated: 24-Aug-2024