|

CONFEDERATE BREAKOUT ATTEMPT ON THE THIRD DAY

McClernand's cold and sleepy soldiers stumbled out of their makeshift

bivouacs as the first warning shots and sounds of the famous "Rebel Yell"

broke the cold morning air.

|

Just as Foote's appearance had disrupted Confederate plans that

afternoon, the unexpected victory at the water batteries confused the

Southern generals as to the urgency of leaving or fighting on. At any

rate, the troops gathered for the massive Confederate assault scheduled

for daybreak on Saturday, February 15, lumbered into position during the

winter night. Snow and wind muffled sounds of the movement. None of the

enemy detected the shifting columns. Buckner's men withdrew from their

entrenchments leaving only a single regiment of 450 men, armed with

shotguns, to face Smith's whole division. Delays proved inevitable,

however, as weary soldiers navigated slick roads. Buckner's force was

still not in position when Pillow and Johnson started their assault at

6:00 A.M. McClernand's cold and sleepy soldiers stumbled out of their

makeshift bivouacs as the first warning shots and sounds of the famous

"Rebel Yell" broke the cold morning air. The big push to flee

starvation, Yankee prison camps, and the stigma of surrender had begun.

Gideon Pillow would style it "the battle of Dover."

|

A CONFEDERATE PRISONER IS QUESTIONED DURING A UNION BIVOUAC ON

THE SNOWY BATTLEFIELD. (BL)

|

The snow, underbrush, and tactical inexperience further delayed any

quick resolution. The fighting turned into a slugfest between the

Confederates' heavy attack columns and McClernand's thin line of

defenders in the vicinity of the Forge and Wynn's Ferry Roads. By 8:00

A.M. however, the Federals were in trouble as fighting enveloped the

country lanes and ravines and blood-stained snow marked points of

contact between the two battle lines. Forrest's troopers dislodged a

stubborn Union field battery and the Confederate infantry slowly bent

McClernand's division back under heavy pressure. As the young Union

soldiers expended their ammunition they simply dropped out of line,

holding their empty cartridge boxes aloft, and began a slow withdrawal,

As one of their brigade commanders groused, "The enemy skulked behind

every hiding place, and sought refuge in the oak leaves, between which

and their uniforms there was so strong a resemblance" that his men could

not distinguish the two.

McClernand sent couriers to Lew Wallace's command post for help. But

the Hoosier general hesitated to act without Grant's instructions.

Somehow, the army commander had disappeared. Early that morning, Grant

had ridden once more to consult with the injured and humbled Foote

aboard his gunboat. Headquarters aides did not know what to do in their

leader's absence, and intervening woods hid the sounds of the unfolding

battle from the command conferees at the river. Thus, by noon, Pillow

and Johnson had carried Confederate fortunes to the brink of success.

"Our success against the right wing was complete," claimed one

Confederate observer. Avowedly, Federal defeat was caused mostly by fatigue,

supply shortages, and inept defensive moves, not by any lack of pluck or

valor. Nonetheless, McClernand's division had been beaten back from its

position.

The attackers were unable to finish their task. By early afternoon,

the relentless drive of Pillow and Johnson, now supported by Buckner,

had gained the objective. The Federals had been driven

back from the Forge Road and westward along Wynn's Ferry Road toward

Fort Henry. Two of McClernand's three front-line brigades had been

crumpled, the third forced into precipitous retreat. Still another

brigade was crushed as it rushed from

reserve. At that hour, the way out of the Fort Donelson trap was open

to the Confederates, stretched along a mile-long battle line. The

soldiers were ready; their leaders were not. During the subsequent two

hours, the Confederate generals yielded the initiative back to the

enemy.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

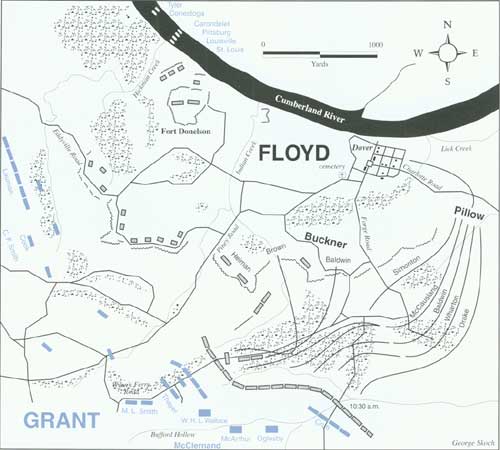

FORT DONELSON —

By February 14, Grant had his army in place and was waiting for the

gunboats to attack Fort Donelson, Flag Officer Foote brought his

ironclads to within 400 yards of the fort before they were forced to

withdraw. This surprised many people on both sides as some thought the

ironclads were unbeatable. This action is shown on the top of the map.

On the night of February 14, the Confederate generals decided to open an

escape route by turning and pushing the Union right flank back along the

Wynns Ferry Road. To accomplish this Confederates massed and launched an

attack east of Dover along the Charlotte Road and south of Dover near

the Forge Road. Shortly after day-break, Pillow initiated the attack

against the Union right flank, followed by Buckner's attack. Although

they offered stiff resistance, the Union right flank was pushed back

along the Wynns Ferry Road. This map shows troop positions as they were

at approximately 1:00 P.M. February 15.

|

A combination of circumstances snatched defeat from victory. Wallace

had finally taken the initiative and moved to a blocking position

astride the Wynn's Ferry Road, where he stymied the Confederate attack.

The attackers ran out of momentum and Pillow, according to his

interpretation, of the original plan, now ordered everyone back to the

trenches preparatory to evacuation. He also noticed signs of a Federal

attack on Buckner's weakly held position in the distance. Buckner,

however, raised strong objection and questioned Pillow's authority to

change the plan. The two generals haggled while their soldiers milled

around awaiting further orders. At that point, Floyd appeared, waffled

between his two subordinates, and then finally ordered all the troops

back inside the defense perimeter.

Just then, Grant returned to the field. Finally found by anxious

couriers, he had ridden hard over icy roads to reach the scene of

catastrophe brewing on his right flank. Conferring with McClernand and

Wallace, Grant sensed that the crisis in the battle, perhaps his own

career, had been reached. He saw McClernand's men "standing in knots"

talking excitedly with no officers giving any directions. He also noted

in his postwar memoirs that the soldiers had their muskets but no

ammunition although "there were tons of it close at hand." Calling out

to an aide to ride along the line with him, he shouted at the stunned

troops: "Fill your cartridge-boxes quick, and get into line; the enemy

is trying to escape and he must not be permitted to do so."

|

THIS CURRIER & IVES PRINT SHOWS THE BAYONET CHARGE AND

CAPTURE OF THE OUTER ENTRENCHMENT'S DURING THE STORMING

OF FORT DONELSON (LC)

|

|

MAJOR GENERAL C. F. SMITH (BL)

|

This worked like a charm. Grant also discerned from prisoners what

was happening on the Confederate line and that the victorious enemy

might be just as demoralized as his own men. Whoever seized the

initiative at this point would achieve victory. Chomping down hard on an

unlit cigar, he ordered McClernand and Wallace simply: "Gentlemen, the

position on the right must be retaken." He also sent word to Foote

requesting a show of force from the gunboats. "It may secure us a

Victory," he noted, adding that "I must order a charge to save

appearances." Grant had grasped a key point. His battered battalions

only wanted "some one to give them a command." Some might be demoralized

and routed, but the majority remained ready to stand and fight.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

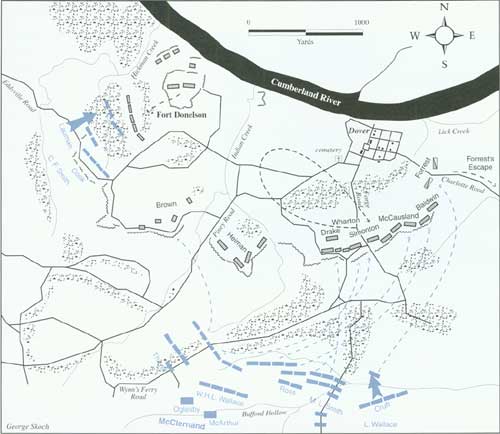

FORT DONELSON —

The way of escape was open, but the Confederate

generals began to argue and debate their next move. While they debated,

Union general Grant arrived. He found that his right flank had been

pushed off the battlefield. Grant correctly assessed the situation. He

concluded that it was an escape attempt. He therefore ordered the lost

ground to be retaken. He further decided that the Confederates must have

massed most of their army in an attempt to break out. Grant thought the

area opposite his left flank must be poorly defended. He ordered General

Smith to attack. By day's end, the Confederates had been pushed back

into their defenses and their right flank was in the hands of the Union

division under General Smith. Unconditional surrender was not long in

coming.

|

Grant also recognized the weakness of Buckner's trench line as he

rode over to C. F. Smith's position. He found his old friend passively

whittling on a stick beneath a tree as if nothing unusual was taking

place. Grant informed him that prisoners and the full complement of

equipment found on Rebel dead indicated a breakout attempt but that the

enemy had thrown all of their strength against McClernand. If Smith

could now assault the trenches before him, he would find little

opposition. "All has failed on the right, you must take Fort Donelson,"

Grant told Smith. Jumping to his feet, the other brigadier responded: "I

will do it!" and moved quickly to organize the assault. As the sounds of

renewed battle indicated a counterattack by Wallace and McClernand,

Smith personally led his division up the steep slope leading to

Buckner's trenches near the Eddyville Road. With battle flags fluttering

in the February breeze, the long lines of blue ascended slowly but

steadily, whipped on by Smith's bellows: "Damn you, gentlemen, I see

skulkers!" One young participant declared later that he was nearly

scared to death, "but I saw the Old Man's white mustache over his

shoulder and went on." Neither logs and brush clogging the hillside nor

the Tennesseans behind the entrenchments could cool the ardor of these

men.

|

SMITH'S 2D IOWA REGIMENT ATTACKS FORT DONELSON'S ENTRENCHMENTS ON

FEBRUARY 15. (LC)

|

|

THE 1862 ENGRAVING DEPICTS THE CHARGE ON FORT DONELSON. (LC)

|

Smith's attackers smashed through the small Confederate holding

force from the 30th Tennessee as Corporal Voltaire P. Twombley of the 2d

Iowa led them over the works. He "took the colors after three of the

color guard had fallen . . . and although almost instantly

knocked down by a spent ball, immediately rose and bore the colors to

the end of the engagement." Thirty-three years later, the aging Hawkeye

veteran would be awarded a Medal of Honor for this deed. In a flash, the

vaunted Confederate outer defense line was breached and Smith stood on

the verge of taking the fort itself. Then, just in time, Buckner's tired

attackers returned to their sector to confront the threat. They formed a

second line of defense on an adjacent ridge, containing Smith's drive.

But they lacked the strength to retake their old trenches. Nor could

they retrieve equipment and begin evacuation. So Buckner and Smith

settled down to firing at each other across a deep ravine. By nightfall,

the fight had gone out of both sides.

Meanwhile, the battle on the Union right also stabilized. Lew

Wallace led the counterattack, in this case in loose or "zouave" order.

But Bushrod Johnson's men had spent their energy of the morning,

conducting a fighting withdrawal but incapable of throwing back the

Union attackers. Once back in their lines, they massed infantry and

artillery fire to check Wallace's drive by dusk. Therefore, the Federals

could accomplish little more than to reoccupy the ground lost during

the day's action. Caring for the casualties and reorganizing units

occupied both sides that evening. Out on the bitterly cold field,

wounded like Lieutenant James O. Churchill of the 11th Illinois could

only lie incapacitated, waiting for rescue or death. Churchill recalled

that he passed the night reciting Thomas Campbell's poem about the cold

December battle of Hohenlinden and reviewing Napoleon's return from

Moscow. He survived, but countless others did not, freezing to death

through no fault of their own. Pillow's so-called battle of Dover had

claimed 3,000 casualties for the two sides without having accomplished

much of anything as a result.

|

|