|

A WINTER ADVANCE ON FORT HENRY

Far to the east in the Kentucky foothills at Somerset, or Mill

Springs, a portion of Buell's command under Brigadier General George H.

Thomas first cracked Johnston's western defense line on January 19,

1862. Yet that was too far away to have any direct effect on the

Mississippi valley or to help local Unionists, who were being bitterly

persecuted by Confederate authorities in East Tennessee. It took Grant

and Foote to galvanize Halleck into action. But it was not easy. Grant,

headquartered at Cairo, Illinois, where the Ohio joined the Mississippi,

received a stern rebuff from "Old Brains," as Halleck was known, every

time he ventured to St. Louis to suggest offensive action. Despite

commendable Mexican War service like so many of his contemporaries,

Grant's old army reputation for drinking and failure preceded him. He

had left the army in 1854 and for the next six years unsuccessfully

plied civilian trades as farmer, real estate salesman, candidate

for county engineer, customhouse clerk, and finally clerk in a

leather store conducted by his two brothers in Galena, Illinois. When

the war came, this West Pointer and Ohio native transplanted to Illinois

raised and commanded the 21st Illinois, then successfully competed for

one of six Illinois state-appointed brigadier's commissions. Together

with his peers, he began the search for fame and rank, successfully

surviving an ill-fated downriver expedition to Belmont, Missouri, and

setting the stage for greater things with a more successful January

reconnaissance in western Kentucky.

|

THE INTENSE FIGHTING AT MILL SPRINGS, KENTUCKY. (LC)

|

|

CITIZENS OF CAIRO, ILLINOIS, POSE OUTSIDE THE LOCAL POST

OFFICE IN SEPTEMBER 1861. GRANT AND MCCLERNANO ARE SHOWN

IN THE CENTER OF THE PHOTOGRAPH NEXT TO THE

PILLAR. (USAMHI)

|

Still, it took the intervention of the older and more respected

Foote to convince Halleck that the idea of a joint army-navy expedition up the

Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers in midwinter might produce results and

that Grant should be the man to lead it. Since the Western Flotilla

belonged to the army at that time, the old sea dog, Foote, given to

feisty Sunday morning sermons from the quarter deck of his ship at sea,

was ready to team with Grant to make the expedition a success. It was

surely his mature and confident manner that won over the ever skeptical

Halleck. Halleck's main task became to provide support to this

pair as well as to secure Buell's cooperation to pin down the enemy from

reinforcing the threatened point on the twin rivers.

Of course, Halleck may simply have decided that the timing was

right. Intelligence had reached his headquarters that Confederate

General P. G. T. Beauregard, hero of Fort Sumter and the Battle of

Manassas, was on his way west with fifteen regiments of reinforcements

for Johnston. Halleck likely panicked at this news so that the

Foote-Grant initiative appeared at the propitious moment. In any case,

he finally approved their scheme on January 30, 1862. News of his

decision hit Grant's Cairo headquarters like a thunder bolt. While the

brigadier's staff bounded around the office in glee, the amused but

taciturn Grant suggested softly that they should not make so much noise.

They might awaken a slumbering Bishop Polk down at Columbus. This

brought more laughter and cheers, but then everyone got down to working

out the details for the expedition.

On February 3, nine transports carrying some 15,000 troops,

animals, supplies, and artillery batteries slipped away from their

moorings at Cairo and steamed slowly

upstream against the rain-swollen current of the Ohio. Picking up

Foote's escort of four ironclad and three timberclad gun boats, they

reached Paducah and turned southward, up the Tennessee River. Slowly

making their way past random cabins and farms and an occasional friendly

inhabitant waving a handkerchief or Union flag, the column aimed at

establishing base camps just out of range of Fort Henry's guns. Many of

Grant's units had participated in his very wet and unpleasant reconnaissance

in western Kentucky behind Columbus in mid-January. Untested in

battle, they were still eager to close with the enemy and to have a

chance to capture forts and secessionist property. An Illinois officer

boasted to his wife that he expected to float up the Tennessee and

capture the two forts before breakfast. Meanwhile, the navy would scout

the Confederate position.

|

GRANT AS A BRIGADIER GENERAL DURING THE FIRST YEAR OF THE WAR. (USAMHI)

|

The force closing on Fort Henry consisted of two divisions. The

first was commanded by another Illinois brigadier, the

politically ambitious former congressman John A. McClernand, the

second by Brigadier General Charles F. Smith, a stern regular army

officer who had been Grant's cadet commander at West Point. Scattered

throughout the land force were other notables, such as Democratic

politicians turned regimental commanders—Illinoisan John A. Logan

and Hoosier Lew Wallace and a smattering of West Pointers and other

experienced militia officers. But mostly Grant's force was a vast array

of farmhands from Nebraska, clerks from Indiana, and river hands and

tradesmen from Ohio and Illinois. On the gunboats served Jack Tars from

the seagoing navy as well as newly minted freshwater sailors from the

army, lured by promises of no more tedious drilling or marches in the

sleet and snow and easier tasks aboard the boats.

Facing this invasion force were Tilghman's

2,800 half-sick, poorly armed, multiattired young soldiers

drawn mostly from Tennessee but also representing Alabama,

Mississippi, Arkansas, and Louisiana.

|

Facing this invasion force were Tilghman's 2,800 half-sick, poorly

armed, multiattired young soldiers—drawn mostly from Tennessee but

also representing Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Louisiana. Morale

had been high until the onset of winter, when the icy blasts and snowy

interludes had chilled secessionist ardor for some of the most ardent

boys from the Deep South. Isolation, high incidence of illness, and the

poor position of the fort dampened the spirits of others. Nonetheless,

young David Clark of the 49th Tennessee wrote his cousin Maggie Bell on

January 18 that he hoped the enemy would attack at either Fort Henry or

Fort Donelson. "I feel confidant that we can whip three times our number

. . . our company will enjoy the fun."

|

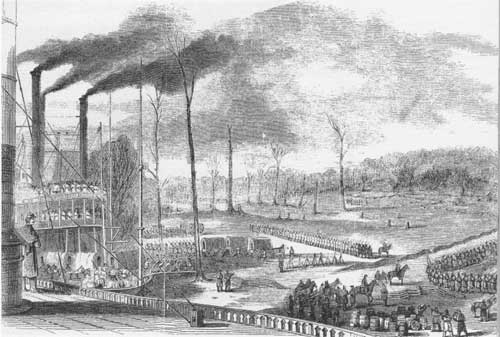

UNION TROOPS DEBARKING FOR THE HENRY-DONELSON CAMPAIGN. (HW)

|

|

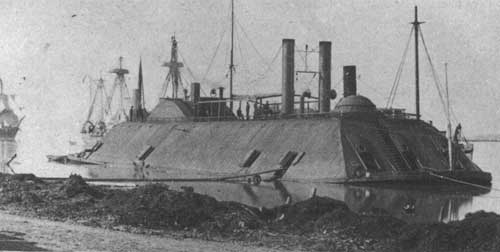

IRONCLADS LIKE THE ESSEX WOULD PLAY A CRUCIAL ROLE

IN THE CAMPAIGN. (USAMHI)

|

With two feet of swollen river water coursing the parade ground and

Fort Heiman of no use for cross fire from across the river, Tilghman was

in a tough position. He controlled access to hundreds of miles of

fertile river-bottom farms and plantations all the way to Muscle Shoals,

Alabama. Just upriver at Danville lay the major river crossing for the

railroad line from Bowling Green to Memphis. The torpedo or mine

obstructions in the river had been swept away or rendered impotent by

the floodwaters. Fort Henry's powder magazines contained inferior

powder (much of it damp or wet) and only eleven of the seventeen heavy

cannon could be brought to bear downriver.

Tilghman decided quickly to abandon Fort Heiman and concentrate his

small garrison inside Fort Henry and its shallow

rifle pits nearby. Eventually, he dispersed his infantry to higher

ground outside the main fort both to guard the land approach to the post

and to avoid the rising water. Most of his men were armed with shotguns

and 1812-era muskets. They lacked sufficient field artillery to counter

Grant's columns. Indeed, Grant's plan of attack called for a combined

naval and land assault on the works. Smith would move against Fort

Heiman (which the Federals did not know was unfinished and about to be

abandoned), while McClernand would march to the rear of Fort Henry and

assault the outlying entrenchments, thereby closing off Tilghman's

retreat route. Foote would steam his gunboats directly against the heavy

seacoast guns commanding the channel approach to Fort Henry.

|

|