|

THE MEANING OF FORTS HENRY AND DONELSON

Grant may have been too optimistic when he felt that the rebellion

was about played out in Tennessee after Fort Donelson. He was similarly

naive in telling his political patron Illinois congressman Elihu B.

Washburn that "a powerful change" was taking place in the minds of

people throughout the state that early spring. Nonetheless, this was a

season of missed opportunities all around. Johnston and Beauregard could

not make the necessary countermove to annihilate Grant's very isolated

expeditionary force on the twin rivers in late February and early March.

But northern generals Halleck and Buell were just as incapable of

exploiting Grant's breakthrough. Halleck thought that working together,

he and Buell could end the war in the West in less than a month. Then

the two fell prey to fears about Grant's exposed position as well as to

which of them should have supreme command in the West. Differing agendas

among the generals, logistical difficulties with supply and movement,

communication problems and uncertain enemy intentions as well as

distance from the nerve centers of war control in Washington and

Richmond stymied both sides after Forts Henry and Donelson. The

expedition that broke open the stalemate in the Mississippi valley

languished for a time. The month following his victories passed in deep

frustration and mounting problems for Grant's army. No Napoleonic-like

"battle for the West" occurred. A Union army-navy team continued to chip

away at Confederate control of the Mississippi River, but it was beyond

the power of either side to effect a quick decision at this stage of the

conflict.

|

THE BATTLE OF DOVER—FEBRUARY 3, 1863

Federal forces never relinquished control of

the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers after the capture of Forts Henry

and Donelson. They established garrisons not only to protect those

rivers as valuable communication and supply arteries but also to

control the region and its inhabitants as part of a slow process of

reconstructing the nation even before the war ended. Their Confederate

opponents, however, made several attempts to recover such control,

always failing in the effort. Partisan and guerrilla bands harassed

Federal garrisons at Dover, Forts Henry and Heiman, and a new Fort

Donelson. A thirty-minute attack by Colonel Tom Woodward and his

partisans on August 25, 1862, did more damage to the town of Dover in

thirty minutes than the previous February's major battle. In the fall of

1864, Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest led a raid to the Tennessee

River and successfully captured and destroyed the Union supply base at

Johnsonville, upriver from Forts Henry and

Heiman. But raiders came to conquer, destroy, and disappear quickly

rather than reoccupy territory for a prolonged period. The most serious

threat to Federal supremacy on the twin rivers took place almost a year

after the Confederate surrender at Fort Donelson. This occurred during

the so-called battle of Dover, February 9, 1863.

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL JOSEPH WHEELER (LC)

|

Following the bloody battle of Stones River, or Murfreesboro, on

December 31, 1862, and January 2, 1863, Confederate cavalry resumed the

task of protecting the flanks of General Braxton Bragg's Army of

Tennessee. They also engaged in raiding Union supply routes and

outposts. Chief of cavalry Brigadier General Joseph Wheeler especially

harassed Union river traffic on the Cumberland and received the thanks

of the Confederate Congress and a promotion. Toward the end of January,

Bragg directed that he take a force, to include the brigades of fellow

generals Forrest and John Wharton, to shut down river navigation at some

specific point on the Cumberland. Forrest had just returned from his own

highly successful West Tennessee raid in December, and his command

needed rest and reoutfitting. Forrest did not personally want to be

subordinated to Wheeler's direction. In fact, misfortune shadowed this

expedition from the beginning.

The Union high command suspended shipping altogether on the river

even before Wheeler's arrival at the Palmyra,

Tennessee, landing. Wheeler was chagrined about the apparent failure

of his mission and, to avoid returning to base without some action,

decided to move twenty miles further downstream to attack the Federal

garrison at Dover. The wisdom of this move was questionable despite

success the previous fall with cowing reluctant enemy garrisons into

surrender. Still, success promised only a handful of prisoners,

temporary occupation of the fortified county seat, and questionable

retaliation for the catastrophic defeat suffered a year earlier at

nearby Fort Donelson. Heavy casualties might ensue, and even remaining

at Palmyra offered a better blocking position on the river. Moreover,

inspection of the command revealed glaring shortages of ammunition and

rations. Forrest's men carried perhaps fifteen rounds of small arms

ammunition and a total of forty-five rounds for their four cannon.

Wharton was only slightly better endowed on this count.

Forrest therefore protested vehemently about assaulting Dover's

garrison. The cold weather, low ammunition, and possible losses argued

against the assault. Moreover, a rumored Federal pursuit column from

Franklin to cut off the expeditions, retreat back to Columbia,

Tennessee, further suggested the inadvisability of the move. The adamant

Wheeler, spoiling for a fight, rejected Forrest's protests, however. The

Tennessean was so nonplussed that he called aside an aide and told him

bluntly: "If I am killed in this fight, will you see that justice is done

by officially stating that I protested against the attack, and that I am

not willing to be held responsible for any disaster that may

result." This request came on the morning of February 3, and even

then his cavalry with the rest of Wheeler's column was pounding down the

Dover road, eager for action.

The expedition soon got it. The Union garrison at Dover was

commanded by feisty Colonel Albert Clark Harding of the 83d Illinois

infantry. He was hardly caught off guard by the Confederate move because

an outpost, about eight miles from Dover, was overrun by Wheeler and

company but survivors were able to spread the alarm. Harding, caught at

his midday meal, immediately telegraphed his superior at Fort Henry,

Colonel William Lowe of the 5th Iowa cavalry, requesting help. He then

prepared his defense at Dover. Bolstering Harding's 600 infantrymen

were two sections of rifled 12-pounder cannon and a 32-pounder heavy gun

that had been removed from the old Confederate water batteries at Fort

Donelson. This force occupied a long rifle pit extending from the

riverbank upstream or east of Dover around the town to the south, and

ending in an old graveyard on the northwestern edge of the village.

Harding positioned the 32-pounder on a swivel mount in a redoubt at the

town square, several hundred yards behind the rifle pit. Two of the

field guns supported this position. The other pair, likewise manned by

Captain James H. Flood's battery, 2d Illinois Light Artillery, with

additional numbers of Harding's infantrymen (under direction of

Lieutenant Colonel A. A. Smith) defended at the graveyard. The Union

position commanded various ravines surrounding the town. But as a final

precaution, Harding herded all women and children at the post aboard two steamboats and sent them

downriver with one, the Wildcat, ordered to find any Union

gunboats and speed them to the garrison's relief.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

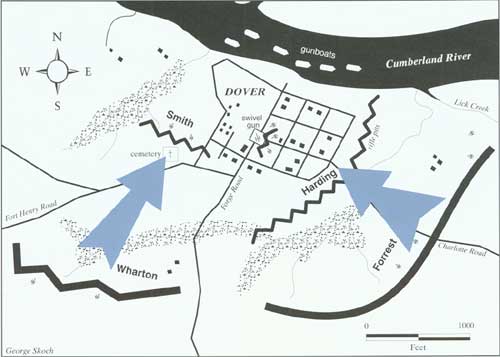

THE BATTLE OF DOVER

This map depicts the positions of the Union garrison under Colonel

Harding and the attacking Confederate forces under General Wheeler. The

attack took place on the afternoon of February 3, 1863.

|

Wheeler, Forrest, and Wharton appeared in the outskirts of Dover

about 1:00 P.M. with some 3,000 Confederates. Skirmishing became brisk

immediately as Forrest was ordered to attack from the east (almost a

reverse of his escape route the previous year), while Wharton's brigade

would simultaneously assault Smith's position. The famous 8th Texas

Cavalry (Terry's Texas Rangers) was sent to guard the Fort Henry road.

Then Wheeler dispatched the customary surrender ultimatum

to Harding. What had worked elsewhere with frightened Union garrisons

did not work at Dover; here the garrison was not intimidated by threats

of superior force even though the note contained the veiled threat: "If

you surrender, you will be treated as prisoners of war; if not, you must

abide the consequences." Harding, a banker by profession and untested in

combat, shot back the terse reply: "I decline to surrender the forces

under my command or the post, without an effort to defend them." Such a

slap in the faces of the Confederate generals immediately elicited a

response. Although their plan called for a coordinated and synchronized

assault, Forrest interpreted a sudden shift in

enemy lines to be an escape attempt. He launched a reckless mounted

charge that was literally blown apart by the Union artillery.

Unable to dislodge the defenders, Forrest's battered men retired to

the crescent shaped ridge running parallel to the Union position east of

town. They dismounted and regrouped and prepared for another attack. Now

supported by their own artillery, Forrest and his men anticipated

greater success. Yet it was not forthcoming for while the Confederate

guns drove Harding's men back to the protection of the redoubt at the

square, the 32-pounder quickly riddled Forrest's dismounted attackers

and the "wizard of the saddle" had a second horse shot from

beneath him that afternoon. Even Wharton fared no better although by

midafternoon he finally succeeded in pushing Smith out of the graveyard,

capturing one of the Federal guns and its caisson. Then, just as his

advance moved into the immediate environs of Dover, Wharton's men ran

out of ammunition. He pulled back, harassed by terrific Union

counterfire.

Dusk settled over the battlefield with the Union position intact and

a bright winter moon illuminating the scene. After surveying the

situation, the Confederate generals concluded that Harding's position

was too strong. Ammunition shortages were acute, and several enemy

relief columns could be seen approaching Dover.

In view of such developments, Wheeler, Forrest, and Wharton decided

to break off the fighting. In doing so, they barely escaped arrival of

Lyon from Fort Henry with portions of the 13th Wisconsin, 71st Ohio, and

5th Iowa cavalry, which pushed through the Texans' roadblock about five

miles west of Dover. The arrival of Lieutenant Leroy Fitch's gunboat

flotilla was equally crucial.

Warned of the Dover battle by the captain of the Wildcat,

Fitch rushed ahead and reached Dover at 8:00 P.M. He had six so-called

tin-clad boats with him, and though their lightly armored sides meant

little at this point, they quickly poured a heavy cannon fire on the

general area held by the Confederates at the close of the action. The

deluge of shot and shell elicited no reply; the dejected Confederates

had already departed. They carried Flood's cannon and caisson with them

as well as quantities of blankets, most coveted by the shivering

Southerners. But they left behind at least seventeen dead and sixty

wounded from Wharton's command while Forrest suffered losses

approximately one-quarter of his thousand-man command. By contrast,

Harding reported thirteen killed, fifty-one wounded and sixteen missing.

He had held his post and defeated three of the Confederacy's best

generals.

That night, the tired and hungry Confederates bivouacked about four

miles from the scene of their afternoon defeat. Their commanders found

shelter in a road-side house, and by the light of a roaring fire,

Wheeler began to prepare his after-action report. He was musing

about the day's events when

Forrest brusquely interrupted. Addressing his superior, Forrest told

Wheeler, "You know that I was against this

attack." "I said all I could and should against it—and now—say

what you like, do what you like, nothing'll bring back my brave fellows

lying dead or wounded and freezing around that fort tonight," he

continued. Disclaiming any disrespect and proclaiming "the personal

friendship I feel for you," the rugged Tennessee horseman added:

"You've got to put one thing in that report to Bragg: tell him I'll

be in my coffin before I'll fight again under your command."

Furthermore, "if you want it, you can have my sword."

Cooler heads prevailed. Wheeler declined Forrest's sword and calmly

admitted that he willingly assumed blame for the failure to capture

Dover. The next day, the weary Confederates once more departed the line

of the Cumberland and, avoiding threatened interception by the Federals,

gained sanctuary south of the Duck River at Columbia on February 17. As

so often in the intervening year, the Confederacy had failed to redeem

the stigma of surrender and defeat in the lower Tennessee and

Cumberland valleys. But now, the Union victory at Dover contributed

another lasting effect on the war in the West. Forrest's determination

not to serve again under Wheeler's command led to permanent separation

of two of the most successful and brilliant Confederate cavalry

chieftains. The two men remained friends until death, but Forrest always

managed to be positioned on the opposite flank of the army whenever he

and Wheeler found themselves thrown together in a campaign. Later in the

year, the two generals were officially separated when two divisions of

cavalry were established, one commanded by Wheeler, the other by Major

General Earl Van Dorn (into which Forrest, again to his disgust was

subordinated.) Eventually, Forrest gained independent command in West

Tennessee and northern Mississippi, where he successfully campaigned

against several Federal opponents. But he never returned to the scenes of earlier ignominy as

Fort Donelson, and Dover remained a synonym for defeat and humiliation

throughout the short life of the Confederacy.

Union leaders decided that their victory at Dover suggested that the

now thoroughly battle-scarred community afforded little strength for

defense of the Cumberland River. So they built a new and improved Fort

Donelson of their own. Located on a hill between the village and the old

Confederate fortifications, this second fort subsequently guarded the

river while providing a rallying point for refugee freedmen and a

recruiting depot for enlisting them into the service of the Union. In

time, the site of the Union Fort Donelson became the present national

cemetery with occupants including not only Civil War dead but the

nation's fallen from more recent contests.

|

THE CEMETERY AT PRESENT DAY FORT DONELSON NATIONAL BATTLEFIELD. (NPS)

|

|

They established the pattern of joint army-navy operations that

would provide the war-winning team for the Union.

|

Sustained by William T. Sherman's support base at Paducah, Grant's

expeditionary force eventually moved upstream and appointments with

destiny at other places and in other battles. Grant personally

weathered difficulties with Halleck and another near disaster when he

was surprised at Shiloh. Most important, however, he and Foote had

demonstrated that Federal land and naval forces working together could

open control of the water highways into the Confederate heartland. They

established the pattern of joint army-navy operations that would

provide the war-winning team for the Union. In addition, their victories

imparted a new sense of purpose to preserving the Union among the

Northern populace. Citizens had discovered a general who fought hard and

won, "Unconditional Surrender" Grant was appropriately viewed as a man

of the people—a no-nonsense combat general who could seize the initiative and

bring success. Despite temporary setbacks, Grant never relinquished that

initiative. He won additional victories and went east in the spring of

1864 to command of all the armies of the Union. In one sense, then, the

war in the West, which opened with the capture of Forts Henry and

Donelson, reached conclusion in Virginia.

There, in Wilbur McLean's Appomattox farmhouse on April 9,

1865, the honor of receiving Robert E. Lee's surrender went to the

hero of Fort Donelson. What was started in the cold February of 1862 on

the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers endured. Three additional years of

strife had incurred more blood and sacrifice—from Shiloh to Vicksburg,

from Stones River, Chickamauga, and Chattanooga to Atlanta and the sea.

And this is not to mention all the battles in Virginia and elsewhere

before it was over. Even Tennessee and Kentucky could not be counted

fully under Union control until the battles of Franklin and Nashville

late in 1864 reflected the last surge of Confederate hopes for

recapturing the upper South. Despite the aversion of Confederate leaders

to prolonged guerrilla warfare, that was precisely what raged across

much of the region until well past the final surrender of organized

Confederate resistance. Still, Forts Henry and Donelson had been a

beginning—for Grant and the Union.

|

THE BATTLE OF MEMPHIS ON JUNE 6, 1862. (BL)

|

|

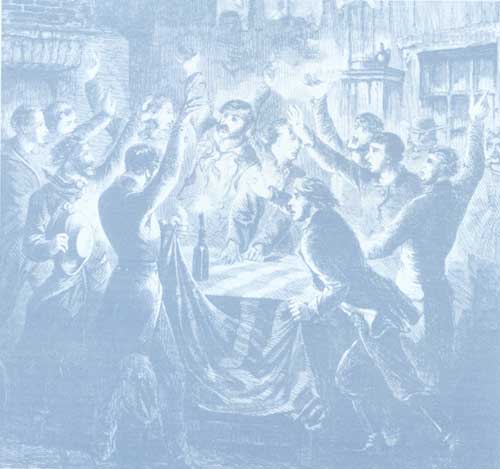

UNION LOYALISTS IN TENNESSEE MAKE A PLEDGE TO THE FLAG. (HW)

|

Most of Grant's principal comrades from the earliest campaign were

no longer with him by the time of Appomattox. True, his aide John A.

Rawlins remained. But Foote, Smith, and James B. McPherson, Grant's

engineer at Fort Donelson, had not survived the war. McClernand had

outstayed his welcome through too much political intrigue and was

eventually thrust aside. Like McClernand, Lew Wallace had suffered

through Shiloh with his chieftain but then fell from favor and was

relegated to administrative assignments despite memories of his heroic

stand, which had saved Grant's army on February 15 at Fort Donelson.

Interestingly, the Hoosiers equally meritorious action at the battle of

Monocacy in Maryland on July 9, 1864,

may have similarly preserved Grant's career. Here, the last

Confederate invasion of Union territory in the East threatened the

nation's capital on the very eve of pivotal national elections. Grant's

focus was on capturing Richmond and Petersburg, and he had neglected

Washington's defense. Only at the last moment did Wallace's action at

Monocacy allow reinforcements from Grant to reach the forts surrounding

Washington and thus save President Lincoln's government. Grant thanked

Wallace but did not restore him to a combat command, the Hoosier's most

cherished desire.

Equally ironic, Henry Halleck eventually finished the war as

Grant's bureaucratic chief of staff in Washington. He had preceded

Grant in going east as top Union general, but the fortunes of war

eventually dictated the need for someone more dynamic and popular to

take charge. Only William T. Sherman, who provided Grant's logistical

support from the first campaign, advanced to take his rightful place

beside Grant in the Union's pantheon of warrior heroes by the time of

Appomattox. It was Sherman, after all, who at one point had persuaded

Grant to persevere and stay the course in those early, transitional

months of frustration after the twin rivers victories. Vicksburg,

Chattanooga, and Appomattox were added to Forts Henry and Donelson as

the result.

|

A RIVER BATTERY AT FORT DONELSON IN SPRING. (PHOTO BY JAMES P. BAGSBY)

|

The long, hard road to victory began then on those two Tennessee

rivers in mid-winter 1862. To the historian Bruce Catton, Forts Henry

and Donelson were not just a beginning but also one of the most

decisive events of the war from which came "the slow, inexorable

progression that led to Appomattox." Little of this was obvious to

anyone in February 1862, of course. Events never become so until later

generations declare them to be so. Writing perceptively in 1882, a

chronicler of the wartime military telegraph operation, William R. Plum,

noted about Fort Donelson, "doubtless, if Grant were to fight that battle again, he

would do better." So would the Confederates, he reasoned. They would

evacuate before they were invested. So, today, we can stand on the

riverbanks of the Tennessee and Cumberland and, viewing the now sylvan

settings of two Confederate forts, ponder what they mean to us. The

facts are inescapable. At Forts Henry and Donelson occurred two

surrenders. Those singular events propelled the Southern Confederacy—however

noble its fighting spirit, however valorous its

fighting men—toward ultimate defeat and demise. The battles

enabled the nation's government to commence the passage toward reunion

and a new nation. They vaulted an unassuming midwestern brigadier named

Ulysses S. Grant toward final victory and, ultimately, the White House.

The rest, as they say, is history.

|

Back cover: Crossing Lick Creek by Gary Lynn Roberts, courtesy

of Newmark Publishing, Louisville, Kentucky.

|

|

|