|

THE LEGACY OF FORTS HENRY AND DONELSON

News of Fort Donelson's fall soon echoed across the Union and the

Confederacy. Northern newsmen and artists had joined the expeditionary

force, and they lost no time in interviewing and sketching participants,

impressions of battle, and events attending the surrender that could be

transmitted back home. Women nurses such as "Mother" Bickerdyke and Mary

Newcomb soon arrived with representatives from aid societies to care for

the injured. War trophies were everywhere, many finding their way into

homeward-bound mail pouches. Northern victory bells pealed and bonfires

blazed in recognition of the glorious victory while to Southerners, the

news sent shock waves of dismay and disbelief. Jefferson Davis admitted:

"Events have cast on our arms and hopes the gloomiest of shadows."

Scores of households everywhere mourned the loss of loved ones who would

not return to fill "the vacant chair."

Truly, the meaning of Fort Donelson could not be measured by heavy

casualty figures as would many subsequent battles. Perhaps 27,000

Federals ultimately faced 21,000 Confederates. Possibly 2,600 of the

former were killed or wounded compared with an estimated 2,000 of the

latter. Approximately, 14,000 to 15,000 Southerners were sent north by

steamboat and train to hastily established prison compounds at Alton and

Camp Douglas, Illinois, Camp Morton at Indianapolis, Indiana, and Camp

Chase, Ohio. Johnson's Island, Ohio, and Fort Warren, Massachusetts,

received the officers. The surrender also yielded an estimated 400,000

rations of rice, 300,000 rations of beef, and 150,000 rations of pork,

as well as 400 barrels of new molasses and 20 hogsheads of sugar.

Counting cannon captured at Fort Henry and, after Fort Donelson, upriver

at Clarksville, upward of seventy-five pieces of artillery fell into

Federal hands on the twin rivers. All such war booty took time to

inventory, and Grant's troops spent the next few weeks securing the

material, recovering from the battles, and getting organized for the

next move. Most important of all, a corps-size element of the western

Confederate army had been swept from the chessboard because of the two

surrenders.

|

CONFEDERATE PRISONERS MINGLE OUTSIDE THE CAPTURED FORT DONELSON UNDER THE

WATCHFUL EYE OF UNION GUARDS. (LC)

|

|

AFTER THE FALL OF FORT DONELSON, FEDERAL GARRISONS

WERE SCATTERED ALONG THE BANKS OF THE CUMBERLAND RIVER.

(NEAR FORT DONELSON BY ALEXANDER RANSOM, COURTESY OF TENNESSEE STATE

MUSEUM COLLECTION)

|

The fruits of victory became obvious within two weeks of the

surrender at Fort Donelson, Foote soon ventured upstream to take

possession of Clarksville, Tennessee, and together with Grant visited

Nashville, vacated by Johnston and occupied by Buell's slowly advancing

army by February 25. Along the twin rivers, Federal forces liberated the

first slaves and destroyed the first civilian property—iron works

and rolling mills—both labeled "contraband of war" because of their

role in the Confederate war effort. Ironically, the facilities belonged

to John Bell, one of the candidates for president of the United States

in the 1860 election. Because of this train of events, the Confederate

theater commander declared the loss of Forts Henry and Donelson as

irretrievable. All he could do at that point was retire with Hardee's

bedraggled force to regroup in northern Mississippi, where they were

eventually joined by the Columbus garrison, evacuated on March 2.

|

NATHAN BEDFORD FORREST

The one bright spot to emerge from the disasters

at Forts Henry and Donelson for the Confederacy was Colonel (later

Lieutenant General) Nathan Bedford Forrest. Escaping with some 1,000 of

his own men as well as others from the doomed garrison on the

Cumberland, Forrest first made his way to Nashville, where he helped

restore order in that panic-stricken city and then joined General

Albert Sidney Johnston's retreating army to Alabama. He subsequently

became perhaps the most famous cavalryman in the western theater and

achieved independent command of the West Tennessee and northern

Mississippi theater of operations late in the war. An untutored genius

at war, Forrest was not a West Pointer but a citizen-soldier like most

of the participants on both sides of the struggle.

Forrest had to overcome countless challenges not only during the

Civil War but over his whole lifetime. Rough-hewn in manner, ferocious

in combat, Forrest spawned many controversies. Yet they reflected this

independent warrior's rise to prominence during the most turbulent

period in our nation's history. From the very beginning, he represented

the arduous life of the Southern backcountry. Born in Chapel Hill,

Tennessee, on July 13, 1821, he was the son of a backwoods blacksmith

living on the edge of poverty. Forrest's boyhood was hard with barely

six months' formal education. He was thrust into responsibility for his

family at age sixteen when his father died. Variously engaged with an

uncle in business at Hernando, Mississippi, and later, on his own as a

prosperous slave trader in Memphis, Tennessee, Forrest eventually

acquired a plantation in Coahoma County, Mississippi, and assumed

public positions as constable,

coroner, militia officer, and Memphis alderman. Still, when Tennessee

seceded from the Union, he chose to enlist as a private in the ranks,

principally to defend his homeland.

Governor Isham G. Harris soon authorized Forrest to recruit what

became the 3d Tennessee Cavalry, and in early actions in Kentucky in

late 1861, he displayed the qualities that would mark his military

career—tenacious in fighting with the enemy and rapid employment of

envelopment tactics. His reputation for hard combat blossomed at Fort

Donelson and later at Shiloh, where he suffered a severe wound during

the closing phase of that battle. When he returned to the army and

command of what would be simply styled Forrest's cavalry brigade, he

staged a daring raid on the Union garrison at Murfreesboro, Tennessee,

on July 13, 1862, winning promotion to brigadier general for his

success. Indeed, together with another intrepid Confederate cavalryman,

John Hunt Morgan (later joined by Joseph Wheeler as the triad of mounted

knights leading the resurgence of Southern fortunes in the western

theater), Forrest became renowned for daring mounted raids against

scattered Union detachments guarding lines of communication and

strategic hamlets in the region.

Forrest crossed the Tennessee River into West Tennessee in December

1862. For two and one-half weeks, he crippled Major General Ulysses S.

Grant's supply lines and stymied the initial campaign against

Vicksburg, Mississippi. Combining bluster and bluff with tough fighting,

Forrest's cavalry wrecked bridges and depots, ripped up miles of

railroad track, burned supplies, and captured hundreds of hapless

Federals unable to cope with his whirlwind assaults. Moreover,

Forrest and his men eluded pursuers until brought to bay at Parker's

Crossroads on December 31. Remarkably, he snatched victory from defeat

by escaping with the majority of his command. The toll on his troops'

endurance and resources perhaps crippled Forrest's efforts to

collaborate effectively with Wheeler in a winter raid on the line of the

Cumberland River, however. This endeavor ended disastrously for their

combined efforts with the serious rebuff at Dover, near the old Fort

Donelson, on February 3, 1863.

Nevertheless, Forrest's recovery came quickly with Middle Tennessee

victories at Thompson Station and Brentwood as well as his successful

capture of Union colonel Abel Straight's force across northern Alabama

and into northwest Georgia in April and May. Here, Forrest displayed his

trademarks of rapid movement, ruse, and

deception to persuade a numerically superior force to surrender.

Couriers from non-existent units and brisk display of forces before

Straight's very eyes inflated the enemy's sense of entrapment. They

suggested Forrest's ability to control a situation completely and to

break the fighting will of his opponent. Here, Forrest was in his

element. When subsequently required to operate more directly with

General Braxton Bragg's Army of Tennessee, the "wizard of the saddle"

performed less enthusiastically. Although he contributed to Bragg's

singular success over William S. Rosecrans at Chickamauga on September

19-20, 1863, Forrest's failure to convince Bragg that rapid pursuit

of the defeated foe would annihilate him produced a bitter altercation

between the two men. Forrest's denunciation of Bragg led to his exile

under the guise of transfer to independent command in Mississippi.

Forrest was called upon once more literally to raise a command as he

constructed his famed cavalry corps of new recruits and conscripts

around a nucleus of veterans. Now a major general, dating from December

4, 1863, he led raids against Federal communications and supply lines in

Tennessee and Alabama and stopped various Union raids into Mississippi

for much of the following year. One raid in April 1864 resulted in the

infamous capture of Fort Pillow north of Memphis and subsequent

slaughter of both white Tennessee Unionist soldiers and their African

American comrades. Modern interpretation generally agrees that Forrest

lost control of his troops in this situation. The internecine hatred of

Confederate for Unionist Tennesseans was matched in tragedy by white

Southerners conviction that blacks under arms (whether in uniform or

not) constituted slave rebellion, punishable under antebellum law

and culture by death. In any event, Fort Pillow would forever be a blot

on Forrest's escutcheon. In June 1864, Forrest routed a superior force

of infantry and cavalry under Brigadier General Samuel Sturgis at

Brice's Cross Roads, Mississippi. The next month he thwarted another

invasion column under Major General Andrew J. Smith at Tupelo, or

Harrisburg, Mississippi, where Forrest suffered another wound. The

intent of these Federal operations was to prevent Forrest from raiding

the Tennessee supply lines of William T. Sherman, then actively

campaigning to capture the strategic Confederate rail and supply center

at Atlanta, Georgia. Forrest was kept busy and away from Sherman's rear.

Only in the autumn could he return to attacking railroads in northern

Alabama and Middle Tennessee, climaxing such activity with the capture of the Union

supply base at Johnsonville, Tennessee (upriver from old Forts Henry and

Heiman), on November 3, 1863.

|

FORREST LEADS HIS MEN ACROSS LICK CREEK. (PAINTING BY GARY LYNN ROBERTS)

|

In many ways, Johnsonville was Forrest's pièce de resistance. Once

more bluff and clever employment of his forces, including use of

captured Federal river craft, secured a brilliant Confederate victory.

This so-called Johnsonville raid netted 4 gunboats, 14 steamboats, 33

artillery pieces, 150 prisoners, and over

75,000 tons of supplies. Total damages to the supply depot itself

approximated $6.7 million. In one historian's opinion, this event

showed Forrest's ingenuity and strength of purpose while strengthening

his reputation as one of the Civil War's top field commanders. Then

Forrest had to cut short his Johnsonville foray to join John Bell Hood's

disastrous Tennessee campaign that foundered before the state capital in

mid-December. Somewhat questionably employed for an independent thrust

to capture nearby Murfreesboro while the main army idly awaited George

H. Thomas' powerful and decisive battle of annihilation, Forrest

nevertheless returned to conduct a brilliant rear guard operation that

ensured escape for a remnant of the Army of Tennessee back to Alabama.

Thereafter, Forrest reorganized his cavalry to defend Mississippi as the

war reached its final stages. He was promoted to lieutenant general to

date from February 28, 1865, but his enfeebled command could not stop

Brigadier General James Harrison Wilson's cavalry raid,

which moved across Alabama (in the image of Forrest's own style) to

destroy Selma, another Confederate logistical center, in March and

April. Forrest recovered in time to surrender his survivors at

Gainesville, Alabama, in May.

After the war, Forrest sought to recover his fortune and life during

Reconstruction, engaging in various business ventures and promoting the

Selma, Marion, and Memphis Railroad as its president.

Ever active and controversial, he became the first grand wizard of

the Ku Klux Klan and campaigned to restore white Conservative Democratic

power in the South. He died in Memphis on October 29, 1877. There an

equestrian statute erected in his memory continues to arouse strong

feelings in the community because of its symbolic presence. He was an

outspoken advocate of speed and ferocity in warfare—the

phrase "war means fighting and fighting means killing"

attributed to him captures well the spirit and appeal of this intrepid

raider. Truly a "wizard of the saddle," Forrest may well have advocated

"getting their first with the most" as a simple but effective maxim of

war. Harsh, even brutal, Forrest was known to respond personally to any

affront to his honor. He bragged of personally killing thirty enemy

soldiers. This Confederate hero of Fort Donelson inspired his men by

personal valor, ability with hand-to-hand combat, and determination to

win victory. Nathan Bedford Forrest personified speed, daring, and

independence of action as a Confederate cavalry leader. Yet his sinister

side at Fort Pillow and with the postwar Ku Klux Klan also suggested the

complexities of a turbulent man in a turbulent era when politics and

race combined with war to create a dark and bloody ground in the

Southern heartland.

|

Certainly in one brilliant stroke, Union forces had rolled

back Confederate territory hundreds of miles. All of

Kentucky and most of Tennessee were clear of Confederate defenders.

|

Certainly, in one brilliant stroke, Union forces had rolled back

Confederate territory hundreds of miles. All of Kentucky and most of

Tennessee were clear of Confederate defenders. Gone were the rich

granaries, the railroad lines, and many industrial facilities. Nashville

became the first Confederate state capital to fall, reputedly costing

the Confederacy $5,000,000 in lost assets. Such losses sapped the

willpower and loyalty of many residents to

the Southern cause. Beauregard told a congressional friend that "we

must defeat the enemy somewhere to give confidence to our friends." The

Confederate commissioner in Paris, John Slidell, wrote home in March:

"I need not say how unfavorable an influence these defeats, following in

quick succession, have produced on public sentiment" in Europe. If not

soon counterbalanced by some decisive victory, he warned, the

Confederacy could forget any early international recognition.

Southerners now realized that a long war lay ahead. They sought

scapegoats for the recent disasters. Floyd, Pillow, and even Johnston

felt the sting of derogatory newspaper editorials, congressional

investigations, and other public denunciation. "We are now at the beginning of

the 'wild hour coming on,'" wrote one Mississippi planter, admitting

that he had pretty much given up since Forts Henry and Donelson were

captured. Colonel Roger Hanson had

fought under Pillow in Mexico, and he declared from prison that to be

under the Tennessean's command once in a lifetime was a misfortune but

twice was more than human nature could bear! Floyd and Pillow were

chastised for their actions, incurring congressional censure, and

banished from future positions of high command. Buckner and Tilghman,

by contrast, would emerge from imprisonment with respect and return to

field command. Johnston kept silent publicly, permitting his friend the

Confederate president to shield him from public ire. His attempted

redemption though the counteroffensive in April ended with his tragic

death at Shiloh. Thus passed any chance for answering his critics and

regaining his lost reputation resulting from the Forts Henry and

Donelson campaign.

|

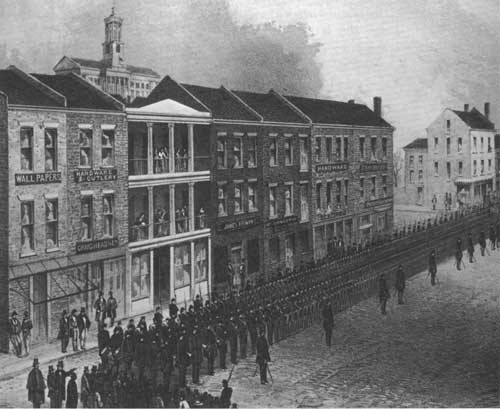

NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE WAS THE FIRST CAPTURED CAPITAL OF A

CONFEDERATE STATE. HERE, THE 51ST REGIMENT OF OHIO

VOLUNTEERS CONDUCTS A DRESS PARADE ON MARCH 4, 1862. (LC)

|

As for the prisoners of war, their incarceration lasted about six

months. While Buckner, Tilghman, and other officers enjoyed liberal,

rather easy conditions at Fort Warren, their men endured cramped living

quarters, poor prison food, and ill treatment from prison guards. A

rather cavalier conduct of prisoner affairs at this point in the war

permitted some contact with home. The prisoners were prohibited from

discussing political affairs and the war, but they could receive

letters, newspapers, clothing, and other personal items, even money.

Inside the prison camps, there was much leisure time for reflection,

exercise, and games as well as penning prison journals, in order, said

Tennessee engineer J. A. Haydon, to prevent "the rust of Prison life"

from eating inwardly on the heart and conscience. Captain John H. Guy, the

Virginia artillery man imprisoned at Johnson's Island, noted that many

of the games there reminded him of his youth but did not tempt him

from his studies. A college graduate, Guy ordered reading material

sent to his men at Camp Douglas so as to improve their minds during

captivity.

|

ORIGINALLY USED TO TRAIN UNION REGIMENTS, CAMP DOUGLAS

WAS CONVERTED INTO A PRISON TO HOLD THE CONFEDERATE TROOPS

CAPTURED AT FORTS HENRY AND DONELSON. (NPS)

|

Several regimental mascots accompanied prisoners to the camps. A

pet rooster and various dogs helped maintain morale and, mostly to a

man, the Rebel prisoners remained cocky. One Kentuckian, when questioned

about a prewar occupation by the Camp Chase adjutant, replied disdainfully,

"Lawyer, hell! I'm a gentleman. Put down my occupation as

'Southern gentleman.'" Still others in a Tennessee regiment refused to

march into prison under a carefully hung United States flag, parting

instead to pass to the sides and thus avoid any appearance of tribute or

allegiance. Tennessee major C. W. Robertson wrote confidently in a

colleague's autograph book at Fort Warren that the Southern cause being

just, her people brave, "her ultimate triumph is certain, though

forty Fort Donelsons shall fall." By autumn, most

of these prisoners had been sent down the Mississippi to Vicksburg

under prisoner exchange arrangements. Many subsequently reformed their

old units and went back into Confederate service. Others, having

experienced enough war, returned home quietly to resume civilian lives.

Some joined partisan or guerrilla or home guard contingents.

|

A SKETCH OF DOVER, TENNESSEE, MADE SOON AFTER THE FALL OF FORT DONELSON. (FL)

|

Guerrilla warfare became widespread throughout much of Kentucky and

Tennessee as the main battles moved further south. A Union Fort

Donelson arose between the old Confederate earthworks and the town of

Dover. It was intended to protect the river traffic from enemy cavalry

and guerrilla raids. For a time, even Dover itself became an armed camp

and the scene in February 1863 of a futile attempt to reestablish

Confederate control of the Cumberland. At this time, Confederate

cavalry under Joseph Wheeler and Nathan Bedford Forrest suffered a stinging

rebuff from an outnumbered Union garrison. The Union accordingly

retained possession of the twin rivers area for the remainder of the

war. Clarksville, Dover, and Forts Henry, Heiman, and Donelson became

positions from which units like the 2d Iowa cavalry and the 83d Indiana policed

the area, reestablished law and order, and continued to chase shadowy

brigands. Fort Henry provided a coaling station for the navy, charged

with patrolling the rivers in light gunboats in an effort to keep supply

lines open to Nashville and the armies operating beyond.

The Federal government also set up a refugee camp and enlistment

depot for former slaves at Fort Donelson. As early as March 1862, the

War Department sought to provide a proper resting place for Union dead

from Fort Donelson. Five years later, once the turmoil of war had

abated, some 670 remains (512 unknown) were placed in a national

cemetery literally on the site of the Federal fort. Needless to say,

Forts Henry and Donelson never became household words in the postwar

South—except, perhaps, as objects of scorn and derision.

|

|