|

THE CAMPAIGN FOR VICKSBURG

An Ohioan named William Tecumseh Sherman called the Mississippi River

the spinal column of the American nation. It was and is an apt

description of the mighty stream that flows from Minnesota to the Gulf

of Mexico, down through the heartland of America. As civil war loomed on

the horizon following the election of the antislavery Republican Abraham

Lincoln to the presidency of the United States in 1860, political and

military leaders of the antislavery North and proslavery South

recognized the truth of Sherman's observation.

Once the sparsely populated far west, the Mississippi River Valley

was growing faster than any other section of the troubled country

Lincoln inherited. More people meant more economic activity; more

economic activity increased the significance of the Mississippi, the

vital transportation artery that linked the West with ports in the Gulf

and on the Atlantic seaboard.

|

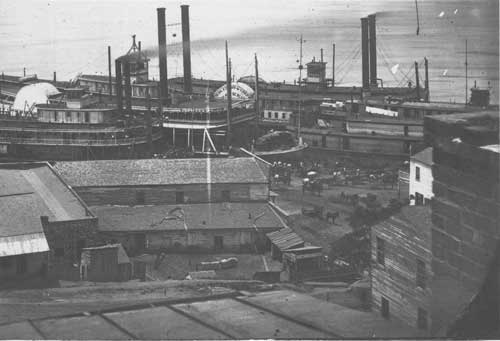

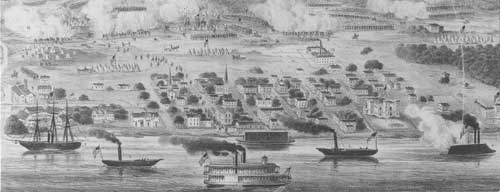

VIEW OF VICKSBURG AND FEDERAL TRANSPORTS ALONG THE WATERFRONT AFTER THE

CAPTURE OF THE CITY. (LC)

|

Political leaders North and South talked of keeping the river neutral

in case war did come. The initial wave of Southern secession from the

Union came in the winter of 1860-61, leading to the Confederate attack

on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, in April 1861. All

hopes of river neutrality evaporated in the smoke of the guns that fired

the opening shots of the Civil War. After Sumter and Lincoln's call for

troops to put down the rebellion, the upper South states of Arkansas,

Tennessee, North Carolina, and Virginia joined previously seceded Texas,

Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina to

form the final version of the Confederacy.

President Lincoln's commanding general, Winfield Scott, came up with

the Anaconda Plan as the Union's initial strategy for subduing the

rebellious South. Scott envisioned using superior Federal naval power to

strangle the Confederacy economically by blockading Southern ports. The

blockade included the mouth of the Mississippi where it entered the Gulf

south of New Orleans, Louisiana.

|

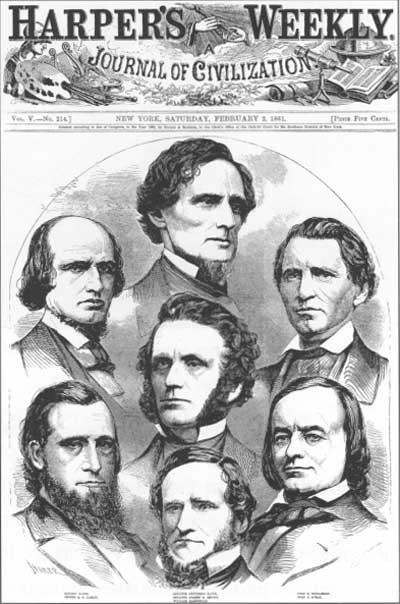

AN ILLUSTRATION FROM HARPER'S WEEKLY OF THE MISSISSIPPI

DELEGATION IN CONGRESS WITH SENATOR JEFFERSON DAVIS ON TOP.

|

|

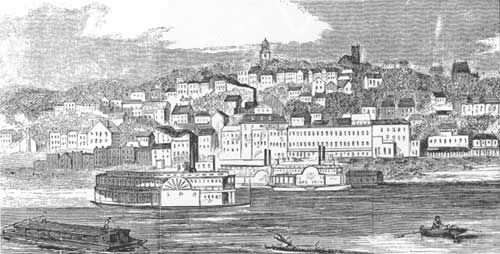

VICKSBURG AROUND THE TIME OF THE WAR. (LC)

|

The Confederacy meanwhile set about fortifying strategic points along

the Mississippi where the river bordered the Confederate states of

Arkansas, Tennessee, and Mississippi and sliced through lower Louisiana.

It quickly became apparent that the point on the river that would be

toughest for the Union to conquer was Vicksburg, Mississippi.

Abraham Lincoln recognized Vicksburg's significance. In a strategy

session with some of his military officers, the Union president pointed

to a map and commented, "See what a lot of land these fellows hold, of

which Vicksburg is the key." The Red River in Louisiana and the Arkansas

and White rivers in Arkansas both emptied into the Mississippi and could

be used for shipping Confederate supplies. "From Vicksburg," said

Lincoln, "these supplies can be distributed by rail all over the

Confederacy." He pointed out also that goods could be gathered along the

Yazoo, which trekked from rich Mississippi Delta farmland into the

Mississippi just above Vicksburg. Lincoln continued, "Let us get

Vicksburg and all that country is ours. The war can never be brought to

a close until that key is in our pocket." Points north and south of that

town could be conquered, he concluded, but "they can still defy us from

Vicksburg."

Incorporated in 1825, Vicksburg at the time of Fort Sumter had a

population of about 4,500, making it one of the larger towns in

Mississippi. The town sat on high bluffs known as the Walnut Hills. A

Confederate engineer described the terrain: "After the Lord of creation

had made all the big mountains and ranges of hills, He had left on His

hands a large lot of scraps; these were all dumped at Vicksburg in a

waste heap."

The waste heap provided Confederates with excellent artillery

positions from which to rake Union gunboats and other shipping that

might attempt to pass along the city's waterfront. Shore batteries could

also wreak havoc on Federal vessels, which had to reduce speed at

Vicksburg because of an exaggerated hairpin turn in the river before it

coursed past the bluffs.

|

ADMIRAL DAVID G. FARRAGUT (USAMHI)

|

|

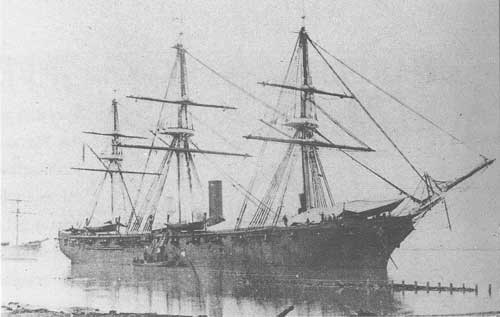

FARRAGUT'S HARTFORD PATROLLED THE MIGHTY MISSISSIPPI. (USAMHI)

|

Union forces had other obstacles to conquer before reaching

Vicksburg, however. North of Vicksburg, Rebels fortified Island No. 10

and New Madrid, Missouri, which lay across the river from the Tennessee-Kentucky

state line. (Missouri and Kentucky had many Southern sympathizers

and were counted as Confederate states by the Confederate

government; both states actually remained in the Union.) Island No. 10

lay at the foot of a deep bend in the Mississippi and thus was ideally

situated to stop Federal downriver traffic. The river made another sharp

turn in front of New Madrid, which made the town an equally attractive

defensive position. Both places fell on April 7, 1862, when Union forces

under Brigadier General John Pope forced the surrender of Confederates

led by Brigadier General William Mackall. Pope's victory opened the

Mississippi to the Union as far south as Fort Pillow near Memphis,

Tennessee.

To the south of Vicksburg, Federal naval vessels closed in on the

city of New Orleans. New Orleans was defended by several small

Confederate forts and two significant structures—Fort Jackson and

Fort St. Phillip—which lay about ninety miles downriver from the

Crescent City. The Confederates had very few naval vessels of any worth

with which to combat superior Federal river forces under the command

of Flag Officer David Glasgow Farragut and Commodore David Dixon Porter.

Between April 25 and 28 Confederate defenses collapsed, Forts Jackson

and St. Phillip surrendered, and a small contingent of Rebel troops led

by Mansfield Lovell evacuated New Orleans.

|

A LITHOGRAPH DEPICTING THE BATTLE OF BATON ROUGE. (THE HISTORIC NEW

ORLEANS COLLECTION)

|

Farragut now took several cruisers and gunboats upriver unopposed to

Vicksburg. The Confederate garrison commander, Brigadier General Martin

L. Smith (promoted to major general in November 1862), refused to

surrender the Hill City, and Farragut ordered a bombardment that would

last from mid-May through July of 1862. Union troops also tried to dig a

canal across the neck of the hairpin turn at Vicksburg but that project,

and the bombardment, failed to reduce the city. The appearance of the

Confederate ironclad Arkansas threatened the security of

Farragut's fleet. Frustrated Federal forces returned to Baton Rouge.

Vicksburg stood firm, but the Union noose was tightening along the

river.

The Confederacy's grip on Vicksburg was also being threatened by

developments east of the river in west Tennessee.

|

The Confederacy's grip on Vicksburg was also being threatened by

developments east of the river in west Tennessee. Forts Henry and

Donelson on the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers respectively fell to an

invading Union army led by Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant and

Federal naval forces under Flag Officer Andrew Foote.

The loss of the forts forced Confederate General Albert Sydney

Johnston to evacuate the important Tennessee capital city of Nashville

and retreat to Corinth in the northeast corner of Mississippi. Grant

followed and set up camp near Pittsburg Landing on the Tennessee River a

few miles northeast of Corinth. Johnston gathered reinforcements and on

April 6 attacked Grant, pushing the surprised Federals back to the banks

of the Tennessee. Johnston was killed in this first clay of the battle

of Shiloh. The next day, Grant, with the benefit of reinforcements,

counterattacked, forcing the Rebel army, now commanded by P. G. T.

Beauregard, back to Corinth. Beauregard later evacuated Corinth as the

huge Yankee army group (made up of three Federal armies), now commanded

by Henry Halleck, closed in. (Grant had been removed from overall

command but was still with the army.) On June 6 Federal forces occupied

Memphis, after the city surrendered to a naval force commanded by

Commodore Charles Davis. The way now lay open for a land campaign

against Vicksburg.

|

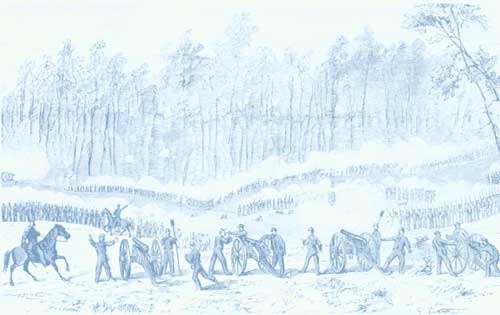

THE SEPTEMBER 1862 BATTLE AT IUKA, MISSISSIPPI. (FRANK AND MARIE WOOD

PRINT COLLECTION)

|

But Halleck wasted a golden opportunity when be decided to break up

his army group in order to solidify the recent Federal successes in

Tennessee. Confederate Major General Earl Van Dorn, commanding at

Vicksburg, used this lull in the Union campaign to order an attack on

Baton Rouge. A small Rebel army led by Major General John C.

Breckinridge attacked the Louisiana capital on August 5, 1862. Brigadier

General Thomas Williams's Federal forces, including vital gunboats, beat

back Breckinridge, and the Confederates lost the Arkansas, which

stalled and had to be scuttled. Yet the Rebels salvaged an important

consolation prize when they occupied Port Hudson on the eastern bluffs

of the Mississippi north of Baton Rouge. The Port Hudson fortifications

provided an important defensive barrier against southern approaches to

Vicksburg.

The Federal army meanwhile tightened its grip on north Mississippi

with two victories in the fall of 1862. On September 19, 1862, Grant,

once more in command, directed his army and that of Major General

William Rosecrans to Iuka, where it clashed with Confederates led by

Major General Sterling Price. The battle developed because each general

was trying to prevent the other from sending reinforcements to armies

in Tennessee. Price inflicted heavy casualties on the Yankees before

retreating because of superior numbers. He marched to the southeast,

then turned southwest to Baldwyn, where he united with troops moving

northward led by Van Dorn, who assumed overall command and led the

combined forces north toward Tennessee. On October 3, Van Dorn turned

east and assaulted Rosecrans's Federal garrison at Corinth. The bloody

two-day battle resulted in heavy Confederate casualties and a retreat.

The Rebels barely escaped being trapped at the Hatchie River west of

Corinth. The debacle led to Van Dorn's removal from command, ended

immediate Confederate threats in north Mississippi, and set the stage

for General Grant's first attempt to take Vicksburg.

|

A CURRIER AND IVES IMPRESSION OF THE BATTLE OF CORINTH. (LC)

|

In planning his campaign, Grant had to take into account myriad

geographical factors. North of Vicksburg on the east side of the

Mississippi lay the Delta region, a flat, periodically flooded area

coursed by many streams of various navigability, including Steele's

Bayou and the Coldwater, Tallahatchie, Yalobusha, and Yazoo rivers.

Then, too, there were a multitude of creeks, many with steep banks, as

well as uncleared swampland infested with tangled undergrowth,

mosquitoes, and various reptiles. On the western side of the Mississippi

in Louisiana, the land was if anything more flat and swampy and would

require much corduroying, that is, building roads of logs.

The bluffs at Vicksburg trailed off to the northeast of the city and

were part of a line of bluffs that extended roughly from Columbus,

Kentucky, to Baton Rouge. Generally, the limestone, sandstone, and

loess bluffs formed an escarpment which offered the Confederates

excellent defensive opportunities, as the Union navy had already

learned. They would also be formidable against any Federal land

operations. The predominantly dirt roads of Mississippi also portended

problems for Grant. Heavy rains would turn them into ribbons of quagmire.

Luckily for the Federals, the weather would be dry during the

weeks of the final campaign in the spring and summer of 1863.

|

THE FEDERALS PLANNED TO TAKE ADVANTAGE OF THEIR NAVAL SUPERIORITY WITH

VESSELS LIKE THE RAM VINDICATOR. PHOTOGRAPHED WITH VICKSBURG IN

THE BACKGROUND. (USAMHI)

|

Both sides attempted to take advantage of geographical factors. The

Confederates fortified the bluffs and filled navigable streams with

obstructions. The Federals planned amphibious operations to take

advantage of their naval superiority. Also, as the course of the coming

campaigns proved, with so much territory to defend around Vicksburg the

Confederates were vulnerable to diversions, and Grant proved to be a

master of diversionary strategy.

Ulysses Simpson Grant was 40 years old when he began his first major

effort to reduce Vicksburg in the fall of 1862. An Ohio native, Grant

graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point, class

of 1843, and was a distinguished veteran of the Mexican War. Despite his

military success, Grant had personal problems, which he allegedly tried

to solve by turning to alcohol, and he eventually resigned from the army

in 1854. Outside the military, Grant failed at most everything he tried,

including farming, customhouse clerk, real estate salesman, politics

(he ran for and was defeated in a St. Louis election for county engineer),

and as a clerk in his brothers' leather store in Galena,

Illinois. The war would end his streak of misfortune. Though his wife

came from a slaveholding family, and he owned a slave (who he soon

freed), Grant wasted no time in offering his services to the Union. The

Federal government in Washington ignored his initial entreaties so he

accepted an appointment as colonel of the 21st Illinois regiment in

June 1861. Finally in August he was appointed brigadier general, thanks

to friendship with a member of the Illinois congressional delegation.

Grant gained his first national attention with the twin victories at

Forts Henry and Donelson. His surrender demands on Fort Donelson led to

him being dubbed "Unconditional Surrender" Grant and a promotion to

major general. Then came the setback of the first day's fight at Shiloh

and calls for his removal from command. Though Henry Halleck came to

take over the army, Abraham Lincoln never seriously considered sacking

Grant. Lincoln dismissed the general's critics with, "I can't spare this

man. He fights."

|

MAJOR GENERAL ULYSSES S. GRANT IN 1862. (USAMHI)

|

|

AT FORT DONELSON GRANT DISPLAYED THE TENACITY THAT WOULD CHARACTERIZE

HIS CAREER. PAINTING BY PAUL PHILIPPOTEAUX. (CHICAGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

The early phases of the Vicksburg campaign proved disappointing for

Grant, but he displayed the tenacity and firmness of purpose that

characterized the remainder of his military career. Undaunted by the

problems inherent in taking the Confederate fortress on the Mississippi,

Grant plunged ahead. Fortunately for the Union, this able commander had

many able lieutenants serving under him, and he established and

maintained a good working relationship with most of them.

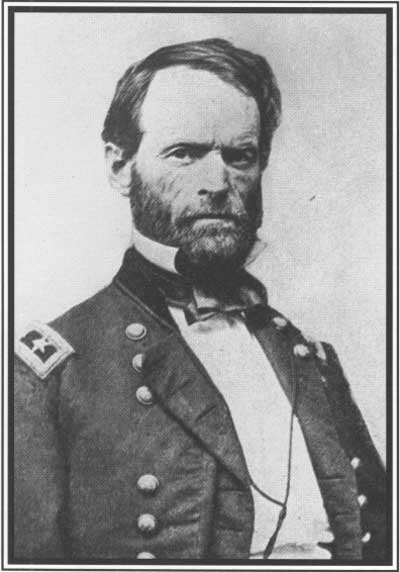

Chief among them and Grant's closest confidant was Major General

William Tecumseh "Cump" Sherman, 42. Like Grant, Sherman's prewar years

had been troubled. Adopted by a prominent Ohio family early in life,

Sherman had many opportunities available to him. With the influence of

his foster father, Sherman managed a West Point appointment, graduating

in 1840. Sherman missed the Mexican War, serving out his post-West

Point years in California. Sherman left the army in 1853 to enter a

banking business in San Francisco that ultimately failed, as did his

attempts at the practice of law in Kansas. In 1859 he became superintendent

of the school that is today Louisiana State University. He made

many Southern friends but strongly opposed secession. Sherman

passionately longed for order in his life and saw the Federal government

as the country's best hope for maintaining order. When war came, Sherman

volunteered to fight for the North, promising his misguided Southern

friends a hard war and a soft peace. He would deliver on both

promises.

Appointed colonel of the 13th U.S. Infantry in May 1861, Sherman was

eventually given a brigade which he commanded in the first battle of

Manassas in July 1861. Cump was one of the few shining stars for the

Federal army in that lost battle. A few weeks later he transferred to

Kentucky to help hold that wavering border state in the Union. Sherman

took his duties seriously, perhaps too seriously. His rough handling of

the press and his insistence that already superior Union forces needed

thousands more men led to charges of insanity by his press enemies.

Sherman survived this dip in his career and went on to serve valiantly

at Shiloh, despite having his camps overrun on the first day. In May

1862, he was promoted to major general and would lead an unsuccessful

flank attack on Vicksburg during Grant's initial operations. During the

final, successful campaign, Sherman led the XV Corps.

|

OLD ABE

Atop the Wisconsin monument in the Vicksburg National Military Park

sits the effigy of an eagle, and therein lies an unusual Civil War

tale.

The eagle, named Old Abe in honor of President Abraham Lincoln, had

been purchased in 1861 by recruits from Eau Claire, Wisconsin. The young

eagle had originally belonged to an Indian who took it from its nest and

later traded it for goods at a country store. The Eau Claire soldiers,

who later formed Company C, 8th Wisconsin, adopted Old Abe as their

mascot. The 8th became known as the "eagle regiment" and delighted in

hearing that Confederates had heard all about their "Yankee

buzzard."

Slightly wounded in the 1862 battle of Corinth, Old Abe survived the

Vicksburg campaign unscathed. He was officially retired from duty in

1864 and donated to the state of Wisconsin. The pampered eagle had his

own room in the basement of the state capitol building. In 1881, Old Abe

got sick from smoke fumes from a fire that burned paints and oils in the

basement. He never fully recovered, dying shortly after the fire. He was

then mounted and placed on display in the capitol until 1904, when the

capitol building and his remains burned.

|

COLOR GUARD OF THE 8TH WISCONSIN WITH "OLD ABE." (OLD COURT HOUSE

MUSEUM, VICKSBURG, MISS.)

|

|

Other significant commanders under Grant's command during the

Vicksburg campaign included Brigadier General Alvin P. Hovey, 41, an

Indianan who had been impressive at Shiloh and who commanded a division

in the XIII Corps; Brigadier General Peter J. Osterhaus, 39, a native of

Germany, who led a division in the XIII Corps; Major General James

Birdseye McPherson, an Ohioan and West Pointer (ranked first in the

class of 1853) who turned 34 in November 1862, commander of the XVII

Corps; Illinois native and Brigadier General (promoted to major general

during the campaign) John A. "Black Jack" Logan, at 36 already earning a

reputation as one of the Union army's best civilian commanders, who

commanded a division of McPherson's Corps; Eugene A. Carr, 32, a New

Yorker and brigadier who led a division of the XIII Corps; and Major

General John A. McClernand, 52. McClernand, like Lincoln, was a

Kentuckian by birth who, also like Lincoln, grew up in Illinois.

|

MAJOR GENERAL WILLIAM T. SHERMAN (LC)

|

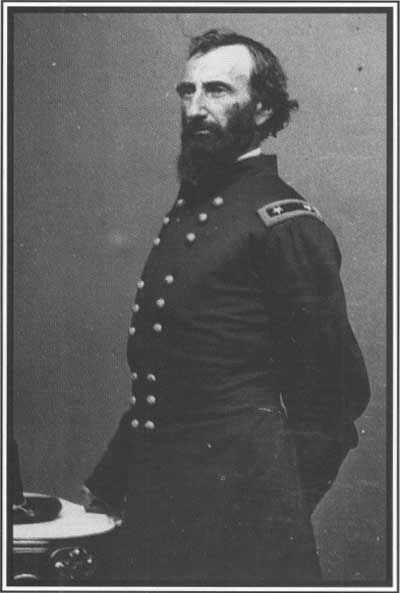

McClernand, a stereotypical political general, led the XIII Corps

during the Vicksburg campaign. His frequent attempts to take the credit

for success, his attempts at political manipulations, and his criticism

of Grant made him unwelcome in Grant's family of commanders. McClernand

would be removed from command before the conclusion of the campaign.

Coming to Mississippi to oppose Grant was Confederate Major General

John Clifford Pemberton. Pemberton, 48, a Pennsylvania native who had

sided with the South because of the influence of his Virginia-born wife,

arrived in Jackson, Mississippi, on October 9, 1862, to take command of

the newly created Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana. He was

soon elevated to lieutenant general. There was nothing in Pemberton's

background that made him a logical choice for the task of defending

Vicksburg and the surrounding area.

A West Pointer, class of 1837, Pemberton had seen action in the

Second Seminole War and the Mexican War. During the latter he had served

as an aide to General William J. Worth and had twice been cited for

bravery. Yet in both wars his primary experience and accomplishments had

been as a staff officer, not a combat soldier. After the Mexican War,

Pemberton served in a variety of posts from the Atlantic coast to the

western territories. At West Point, he had been very popular with his

classmates and seldom missed a party, but his years in the military

seemed to harden his personality. Before the Civil War Pemberton had

become something of a martinet, so much so that an angry private at one

post had almost killed him.

|

MAJOR GENERAL JOHN A. MCCLERNAND (USAMHI)

|

After making the agonizing decision to fight for the Confederacy,

Pemberton came to his wife's native Virginia, instructed recruits, and

then supervised the placement of artillery batteries along rivers and

coastal areas east of the Confederate capital of Richmond. By this time,

he had risen from a colonel of artillery in the Virginia state army to

brigadier general in the Confederate army. From his West Point days

forward, Pemberton had showed a talent for playing politics in the

military, and this may account for his rapid rise in rank, which

continued until he was promoted to lieutenant general on the threshold

of the Vicksburg campaign.

Pemberton's career took a fateful turn when he reported to

Charleston, South Carolina, in November 1861 to serve in the Department

of South Carolina and Georgia (and parts of Florida) under Robert B.

Lee, future famous commander of the Confederate Army of Northern

Virginia. Eventually Lee returned to Virginia, and Pemberton, by reason

of his seniority among the local brigadiers, was promoted to major

general and took command on March 14, 1862. Pemberton's experiences in

South Carolina were not pleasant. After a shaky start, he exhibited some

of his administrative talents in supervising the numerous logistical

problems of the department, but the strategic and tactical concepts he

employed deeply angered South Carolina officials. For example, he wanted

to evacuate Fort Sumter so as to constrict his defensive line. But Fort

Sumter was the symbol of secession and the birth of the Confederacy, and

South Carolina governor Francis Pickens was enraged at the very idea of

giving it up. Pemberton's inexperience in dealing with civilian

officials was apparent, as was his lack of public relations expertise in

general.

|

A MODERN-DAY VIEW OF FORT SUMTER. (NPS)

|

|

A PORTRAIT OF LIEUTENANT GENERAL JOHN CLIFFORD PEMBERTON. (SOUTHERN

HISTORICAL COLLECTION, UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA)

|

A major turning point for the beleaguered general came when he told

the mayor of Charleston that, given the choice, he would give up the

city rather than sacrifice his army in its defense. The mayor told the

governor, who passed it along to Richmond. Lee, now acting as military

adviser to Jefferson Davis, sent Pemberton a lengthy message stating in

no uncertain terms that Charleston must be held at all costs.

Unfortunately for the Confederacy, Pemberton took Lee's words more

literally than Lee probably meant them.

Pemberton's performance in his department continued to attract

criticism until President Davis finally removed him from command in

August 1862. Pemberton wanted to return to Virginia, but Davis, who

still had confidence in his general and was miffed at Pemberton's South

Carolina critics, decided to send Pemberton to Mississippi. Even though

allegedly endorsed by Lee and Adjutant General Samuel Cooper, Davis's

decision remains difficult to understand. While combat opportunities in

South Carolina had been sporadic, they surely would be plentiful in the

Vicksburg area, and Pemberton still had no experience at leading an

army in the field. He also had shown little ability to boost morale, to

inspire confidence in his leadership. His administrative talents had

served him well enough, but his new command required much more.

|

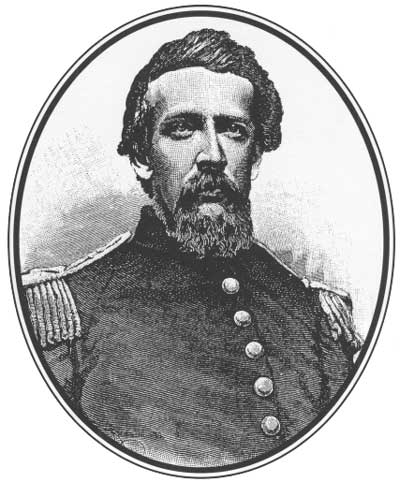

MAJOR GENERAL JOHN S. BOWEN (BL)

|

|

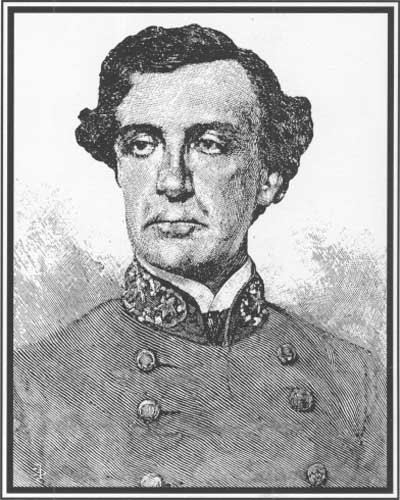

MAJOR GENERAL MARTIN L. SMITH (BL)

|

Unlike Grant, Pemberton did not have a close lieutenant like Sherman

to support him during the coming campaign. Pemberton's generals were

dramatically divergent in talent, ranging from mediocre to superior. He

was never able to mold them into a successful fighting team. John S.

Bowen was Pemberton's best combat general. The 32-year-old Bowen, a

native of Georgia, graduated from West Point in 1853. He resigned from

the army after three years and was working as an architect in St. Louis,

Missouri, when the war came. Captured with pro-Confederates at Camp

Jackson near St. Louis in 1861, Bowen was released and became colonel of

the First Missouri (Confederate) Infantry. He initially saw action at

Columbus, Kentucky, and was promoted to brigadier general in March 1862.

He led a brigade in Breckinridge's division at Shiloh, where he fell

wounded. He also participated in the Corinth campaign, fighting the

fierce rear-guard action that saved Van Dorn's army. He later brought

charges against Van Dorn, who was eventually cleared by a

court-martial. A born fighter, Bowen had little patience with

incompetent superiors or subordinates. Yet his men loved him despite his

martinet tendencies. Had Pemberton had a few more Bowens to send into

the field, the Vicksburg campaign might have turned out very

differently. Before the campaign concluded, Bowen's performance earned

a promotion to major general.

One of Bowen's top subordinates, Colonel Francis Marion Cockrell, 28,

a lawyer by profession, also performed brilliantly during the campaign.

A native of the "Show Me" state, Cockrell would command the Missouri

brigade in Bowen's division and would be promoted to brigadier general

shortly after the fall of Vicksburg.

|

CONFEDERATE BATTERIES DEFENDED VICKSBURG AND WERE STRATEGICALLY PLACED

UP AND DOWN THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER. (AMERICAN HERITAGE PICTURE

COLLECTION)

|

Other Pemberton lieutenants included Major General Martin Luther

Smith, 43, a New Yorker and West Pointer, class of 1842, with Southern

sympathies and a Georgia wife, who had engineering skills and commanded

the Vicksburg garrison during various aspects of the campaign; Major

General William W. Loring, 44, a North Carolinian, Mexican War veteran,

and troublemaker, who came to Mississippi after service in Virginia and

commanded a division in Pemberton's army; Brigadier General Lloyd

Tilghman, 46, a Maryland native and West Pointer (class of 1836), an old

friend of Pemberton with whom he would feud during the campaign, who

commanded a brigade in Loring's division; Major General Carter L.

Stevenson, 45-year-old Virginian, West Pointer (class of 1838), veteran

of the Mexican War and the Confederate invasion of Kentucky in 1862, who

commanded a division under Pemberton; Brigadier General John Gregg, an

Alabama native, 34, who led a brigade of Texans and Tennesseans;

Brigadier General Martin E. Green, 47, a Virginian who lived in Missouri

in 1861 and organized a Missouri cavalry regiment before commanding a

brigade in Bowen's division; and Stephen D. Lee, 29-year-old South

Carolinian and West Pointer (class of 1854), an experienced artillerist,

who served in Virginia until being assigned to command Pemberton's

artillery in Vicksburg in November 1862.

Joseph E. Johnston was forced into playing a role in the campaign

that he did not want and which set the stage for an everlasting

controversy about his conduct.

|

Other officers destined to play significant roles in the coming

campaign included Earl Van Dorn, Brigadier General Franklin Gardner, and

General Joseph Eggleston Johnston. Van Dorn, a 42-year-old

Mississippian, was placed in charge of Pemberton's cavalry after the

former's defeats at Pea Ridge, Arkansas, and Corinth. Events showed that

cavalry suited Van Dorn's talents much more than army command. A New

York native, Gardner, 39, was given command early in 1863 of Port

Hudson, where he would suffer the same fate as Pemberton.

Joseph E. Johnston was forced into playing a role in the campaign

that he did not want and which set the stage for an everlasting

controversy about his conduct. The 55-year-old Virginian had not had a

positive war experience. There had been quarrels with Jefferson Davis

over Johnston's position of seniority among Confederate generals, and he

had lost command of the Confederate army in Virginia following a severe

wound at Seven Pines in May 1862. By the time he recovered, the army had

passed permanently to the command of Robert E. Lee.

|

|