|

As the light of dawn streaked through the tangled woodland, Union

commanders looked upon the surrounding landscape in astonishment. All

around they saw a maze of thick canebrakes, crisscrossing ravines, steep

valleys, and broad and narrow ridges complicating any plans of

attack.

General McClernand arrived at dawn and was briefed on the situation.

He learned that a road veering northwest from the Shaifer house

ultimately led to the Bruinsburg road. A local black man warned

McClernand that Confederate troops (Tracy's Alabamians) were approaching

from that direction. McClernand sent Peter Osterhaus's division to meet

this threat on the Union left flank.

Meanwhile, Tracy got an urgent message to send a regiment and a

section of artillery to reinforce the hard-pressed Green on the Rodney

road. At this point, the Rebels had only 2,500 men present on the field;

cooperation between Tracy's and Green's widely separated wings was

essential but difficult because of the terrain.

Help was on the way. William Baldwin rushed his brigade forward to

the fight. The Missouri brigade, led by able Colonel Francis Cockrell,

waited impatiently at Grand Gulf. Bowen had been unwilling to gamble

that Grant had given up the idea of crossing at Grand Gulf. Once he

arrived on the battlefield about 7:30 A.M., Bowen recognized his error.

A courier raced to Grand Gulf with orders for the Missourians to hurry

to Port Gibson.

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL PETER J. OSTERHAUS. (NA)

|

While the Confederates waited for reinforcements, Osterhaus pressured

Tracy's wing, using his superiority in numbers to great effect. The

timely arrival of another Alabama regiment from Vicksburg helped, but

suddenly the Rebels suffered a crisis in leadership. Tracy fell dead

from a Union sharpshooter's bullet. Colonel Isham Garrott assumed

command but had no idea of Tracy's battle plan. Garrott asked for

instructions from Green and received a vague reply to maintain his

position "at all hazards."

Osterhaus continued to extend his line in both directions, but

Garrott's men, thanks to their tenacity and geographical factors,

thwarted Yankee attacks. Finally, Osterhaus decided on a thrust at the

Confederate right while massing for an all-out assault on Garrott's

center. Then Osterhaus hesitated and waited until Grant, who had arrived

at the front, sent a brigade from Logan's division.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

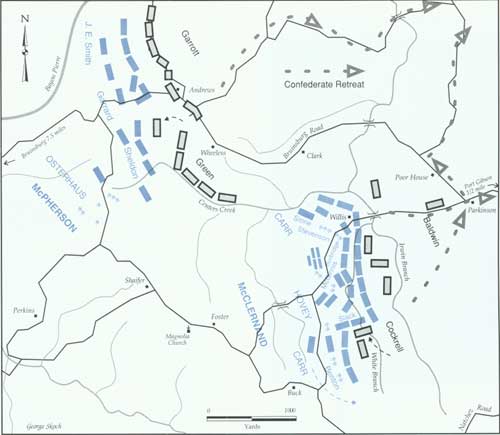

BATTLE OF PORT GIBSON, MAY 1, 1863, 8:15 A.M. TO 10 A.M.

The action opens as John McClernand's corps bumps into Martin Green's

Confederates posted around Magnolia Church. Peter Osterhaus's division

moves to meet Confederates commanded by Edward Tracy. Though Tracy is

soon killed, his successor, Colonel Isham Garrott, holds the troops

together and stops Osterhaus until late in the afternoon. A. P. Hovey's

and Eugene Carr's divisions struggle with Green's Rebels around Magnolia

Church. After much bloody fighting, the outnumbered Green falls back to

Centers Creek.

|

On the Rodney road, General Green's small force had been routed by

Carr's and A. P. Hovey's divisions. Two cannon from the Virginia

Boutetort Artillery had been lost (the Virginia artillerymen were the

only participants from that state in the Vicksburg campaign) as well as

a caisson and 200 prisoners. Although the terrain had aided Green's

stand near the Magnolia Church ridge, he had been heavily outnumbered.

Bowen sent Green's shattered command to the right wing to help

Garrott.

General Baldwin's brigade arrived from a forced march through a

chaotic Port Gibson to take up the fight for the Confederates on the

Rodney road. Cockrell's Missourians made a quick march from Grand Gulf

and waited in reserve on Baldwin's wing. Bowen now called in all his

troops guarding the Bayou Pierre and Big Black waterways.

On the Bruinsburg road, Osterhaus renewed his attacks on Garrott,

gradually caving in the Rebel right flank. At 5 P M Green, senior

commander on the scene received a message from Bowen to hold out until

sunset. If Green could not take the offensive by then, he could retreat.

Green, aware the day was lost, thought sunset was close enough and

ordered a withdrawal.

The 6th Missouri Confederate regiment, isolated from the other

commands on the Bruinsburg road, narrowly escaped being captured during

the retreat. By faking an attack, most of the Missourians managed to

escape, although the 49th Indiana recognized the ruse in time to bag 46

prisoners. The rest of Green's command retreated across Bayou Pierre

toward Grand Gulf.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

BATTLE OF PORT GIBSON, MAY 1, 1863, 11 A.M. TO 5:30 P.M.

Green's troops are sent to reinforce Garrott. Federals are reinforced by

Logan's division of McPherson's corps. Around 5 P.M. a Federal attack

forces Bowen to order Garrott and Green to pull back. On Bowen's left

flank Baldwin takes up the fight after Green's retreat. Cockrell and his

Missourians go to the left of Green's line and punish Slack's troops

along the White Branch of Centers Creek. Infantry from Smith's division

and Hovey's artillery stop Cockrell. The retreat on the Confederate

right had begun, and Baldwin and Cockrell withdraw.

|

While victory had finally come on the Union left, McClernand's blue

column on the right had encountered stubborn opposition after Green's

defeat. McClernand and Richard Yates, the governor of Illinois, along to

observe the battle, had made political speeches before Grant quietly

urged pursuit of the retreating Confederates. The Yankee pause gave John

Bowen valuable time.

On the Rodney road, Bowen anchored his new defensive line in front of

a narrow ridge between the White and Irwin branches of Willow Creek.

Bowen had decided that he would develop his defense in this lower

terrain after observing the action on the broad Magnolia Church ridge.

There his troops had been susceptible to artillery fire. Down in the

bottom, the ravines and vegetation gave the Confederates better

cover.

|

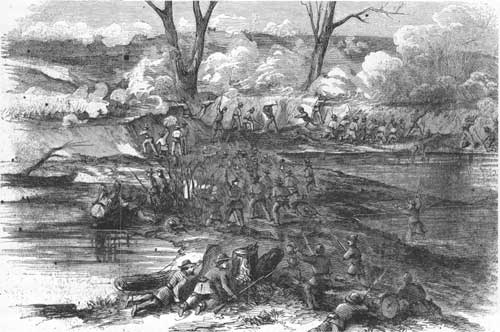

THE SIXTH MISSOURI (C.S.A.) REGIMENT FOUGHT BRAVELY THROUGHOUT THE

VICKSBURG CAMPAIGN. THEY ARE SHOWN HERE FIGHTING OUTSIDE VICKSBURG. (LC)

|

Bowen's strategy worked for several hours as the battle along the new

Rebel defensive line developed into a bloody stalemate. But Bowen feared

that the Federals might extend their lines southward to a road that led

around his position into Port Gibson. He ordered Cockrell's reserve

beyond the Confederate left to assault the Yankee right.

Hovey saw Cockrell's column and tried to get reinforcements to the

danger point. Before he acted, the Missourians attacked, devastating

James Slack's Union brigade. But massed artillery and superior numbers

of Union infantry soon forced the Missourians to retreat grudgingly.

His right secured, McClernand tried to whip Baldwin as he had beaten

Green, with a massed frontal assault. The Confederate position here was

stronger, and Green's and Cockrell's attack had drained some of the

forces McClernand counted on for his attack. So McClernand let the

battle develop on its own, but his numerical advantage, enhanced with

the arrival of two brigades from Logan's division, eventually collapsed

the Rebel left.

|

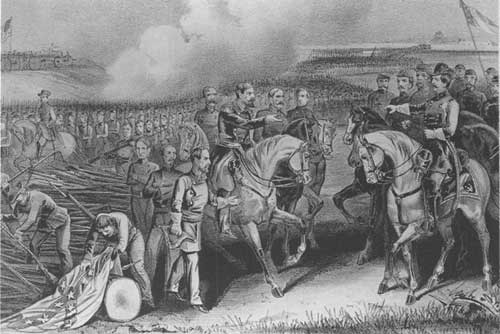

A THEODORE DAVIS SKETCH OF LOGAN'S DIVISION CROSSING THE BAYOU PIERRE IN

PURSUIT OF THE CONFEDERATES. (LC)

|

Bowen ordered a retreat, and his men escaped north across Bayou

Pierre and its fork, Little Bayou Pierre, firing bridges behind them.

Outnumbered more than three to one, Bowen and his subordinates had

fought brilliantly, delaying Grant from just after midnight until near

sunset of May 1, inflicting 875 casualties on Grant's army while losing

787. The little Confederate force at Port Gibson had bought Pemberton

time; it remained to be seen how well he would use it.

A victorious Grant decided to keep up the pressure while he had

momentum. He had considered turning south to join Nathaniel Banks and

attack Port Hudson. But Banks was currently operating on the Red River

and could not effect a junction for several days. So Grant left Port

Hudson to Banks, who had the Federal XIX Corps, which considerably

outnumbered Rebel defenders.

Pemberton decided to abandon Port Hudson and had wired Franklin

Gardner to rush his forces to Vicksburg. But President Jefferson Davis

intervened, wiring Pemberton, "To hold both Vicksburg and Port Hudson is

necessary to a connection with the Trans-Mississippi." Davis should have

left such a decision to his field commander, and Pemberton, his

confidence badly shaken by the loss of Port Gibson and subsequently

Grand Gulf, should have protested. Pemberton, however, immediately

wired Gardner to remain in the Port Hudson works with 2,000 men (about

5,000 reinforcements later joined Gardner's force).

|

FARRAGUT PASSING THE STEEP RIVERBANKS AT PORT HUDSON. PAINTING BY FRANK

SCHELL AND THOMAS HOGAN. (AMERICAN HERITAGE PICTURE COLLECTION)

|

|

THE SURRENDER OF PORT HUDSON AS ILLUSTRATED IN THIS CURRIER AND IVES

PRINT. (LC)

|

On May 21 Banks's army began siege operations. The siege of Port

Hudson included two desperate assaults by Federal troops, including

Louisiana blacks fighting for the Union, on May 27 and June 11, both of

which were beaten back by equally desperate Rebel defenders.

Confederate operations in Louisiana intended to relieve Port Hudson

failed but kept Union forces occupied and constantly on the alert. A

frustrated Banks could not force a surrender until July 8, four days

after Pemberton's surrender of Vicksburg made Port Hudson untenable.

Grant decided to move north-northeast, feinting toward the Big Black

with his true objective being the Southern Railroad that connected

Jackson and Vicksburg. Once astride this Confederate supply line, Grant

could turn west and attack Vicksburg. Grant marched with two corps,

McClernand's XIII and James McPherson's XVII. Sherman had abandoned his

Snyder's Bluff demonstration and was hurrying his XV Corps to join

Grant. When Sherman arrived, Grant would have a force of some

45,000.

Wagons from a beachhead established at Grand Gulf kept Grant's army

supplied. After the war, Grant originated a myth, perpetuated by many

historians ever since, that when he left Port Gibson and moved toward

central Mississippi he cut his supply line. His army lived off the land,

he said. The truth is that well-supplied wagon trains trailed the army

inland.

A nervous John Pemberton decided that to counter Grant's march, all

Confederate troops must be consolidated west of the Big Black to protect

Vicksburg. Pemberton never considered taking the offensive, despite the

urging of some of his officers. Joseph Johnston had wired Pemberton on

May 1 to unite all his forces to strike Grant, even if that meant

abandoning Vicksburg. The wire gave good advice but arrived too late to

keep Grant from winning at Port Gibson. Pemberton would have ignored

Johnston anyway. President Davis had said to hold Vicksburg, and

Pemberton had learned in South Carolina that if ordered to hold a spot,

he must do so.

When William Loring arrived on the battle front above Port Gibson, he

took command of Confederate forces and led a retreat to the Big Black at

Hankinson's Ferry. Reinforcements from Vicksburg arrived, and Loring had

an opportunity to strike McPherson's corps, temporarily isolated as the

Yankees spread out on a broad front moving northeast. Loring, seemingly

reflecting Pemberton's defensive state of mind, let the chance go

by.

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL JOHN GREGG (NA)

|

Loring led his troops north toward Pemberton's concentration area

between Edwards and the Big Black. Pemberton had received intelligence

reports that Grant was headed for the railroad near Edwards. Pemberton

intended to place his main battle line along the high bluffs on the west

bank of the Big Black.

What if Grant decided to attack Jackson instead? Loring persuaded

Pemberton to send a detachment east just in case. Brigadier General John

Gregg, on his way to reinforce Pemberton from Port Hudson, received

orders to take his brigade of some 3,000 men to Raymond. Gregg was to

keep an eye out for the enemy but not to fight if outnumbered. Pemberton

was risking isolating much needed troops, especially with only a small

number of state cavalry, inexperienced compared to Yankee veterans,

available to screen Gregg's position. Through confusion of orders,

regular Confederate cavalry intended to assist Gregg had been sent in

the wrong direction.

|