|

An aide awakened Gregg at dawn on May 12 with the information that

Yankees were coming up the Utica road toward Raymond. Gregg, on the

basis of this and information from Pemberton's headquarters, completely

misread the situation that faced him. He thought that the entire

Federal army was wheeling to its left to attack the railroad somewhere

in the Edwards area. So he assumed that the Federals moving toward

Raymond must be a rear guard or part of a screening movement on the

extreme right flank of Grant's army. Actually, the approaching Yankees

were the vanguard of McPherson's entire corps which formed the right

wing of the Union army.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

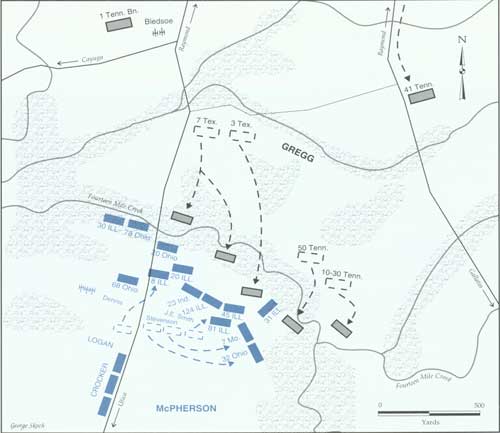

BATTLE OF RAYMOND, MAY 12, 1863, NOON TO 1:30 P.M.

General John Gregg is ordered by Pemberton to attack Grant's flank and rear.

Pemberton believes Grant is turning from Jackson toward Big Black. He

thinks Federal troops moving toward Jackson are carrying out a feint.

When Gregg gets reports that a Union column is coming toward Raymond, he

assumes it is the feint mentioned by Pemberton. These troops are the

advance of James McPherson's corps. By the time Gregg realizes he is

heavily out numbered, his small force is engaged with the enemy along

Fourteen Mile Creek.

|

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

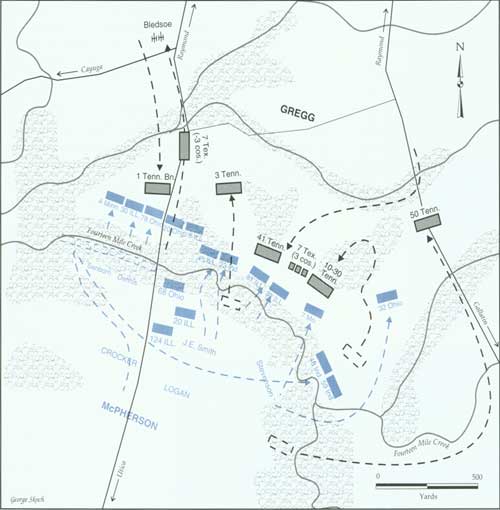

BATTLE OF RAYMOND, MAY 12, 1863, 1:30 TO 2.30 P. M.

The battle is marked by uncoordinated attacks and counterattacks. Dust and smoke

hamper both sides' efforts. Overwhelming Federal pressure finally pushes

back Gregg's right, forcing him to order a general retreat back

through Raymond and on to Jackson. His brigade will not be able to fight

any more for Pemberton because Grant, who up to this point has been leaning

toward moving on the Big Black, decides to go on to Jackson to

remove the threat of Johnston, thus preventing Gregg from marching his

men to Pemberton at the Big Black. Gregg and his men join Joseph

Johnston in Mississippi's capital city.

|

The aggressive Gregg attacked about two miles south of Raymond in the

Fourteen Mile Creek area. As the fighting developed, Gregg soon realized

his mistake, but his men valiantly fought for several hours before

sheer weight of numbers forced him to retreat. Since it was too

dangerous to withdraw across the enemy front toward Edwards, Gregg

marched his battered brigade to Jackson. He had suffered 515 casualties

while inflicting 446 on McPherson's XVII Corps. His decision to fight

rather than withdraw immediately had also cost Pemberton much needed

troops at Edwards.

More important, the fight at Raymond caused Grant to change his

strategy and altered the entire course of his campaign. Gregg's stiff

resistance and scouting reports that indicated Joseph Johnston had come

to Jackson to assemble an army to aid Pemberton convinced Grant that he

could not risk turning his army west. Pemberton just might march east,

or Johnston might march west, or both, catching Grant between two

Confederate armies. So Grant decided to attack Jackson first before

turning to meet Pemberton.

|

SLEEPLESS DAYS AND NIGHTS

Emma Balfour and her physician husband, William, lived next door to

General John Pemberton's headquarters in Vicksburg. The Balfours

rejected cave life and remained in their house during the siege. Emma kept a

diary, part of which survived and is stored in the Mississippi

Department of Archives and History. The following is an excerpt from

the May 30 entry:

"We got thoroughly worn out and disheartened and after looking to

see the damage, went into the parlor and lay on the sofas there until

morning, feeling that at any moment a mortar shell might crash through

the roof..."

|

"At 12 o'clock the guns all along the lines opened and the parrot

shells flew as thick as hail around us! Then there was commotion! We had

gone upstairs determined to rest lying down but not sleeping, but when

these commenced to come it was not safe upstairs so we came down in the

sitting room and lay down upon the bed there, but soon found that would

not do as they come from the south-east as well as east and might strike

the house. Still from sheer uneasiness we remained there til a shell

struck in the garden against a tree, and at the same time we heard the

servants all up and making exclamations. We got thoroughly worn out and

disheartened and after looking to see the damage, went into the parlor

and lay on the sofas there until morning, feeling that at any moment a

mortar shell might crash through the roof, though we felt comparatively

safe from the others. We have slept scarcely none now for two days and

two nights. Oh! it is dreadful. After I went to lie down while the Dr.

watched every shell from the machines as they came rushing down like

some infernal demon, seemed to me to be coming exactly on me, and I had

looked at them so long that I can see them just as plainly with my eyes

shut as with them open. They come gradually making their way higher and

higher, tracked by their firing fuse till they reach their greatest

altitude—then with a rush and whiz they come down furiously, their

own weight added to the impetus given by the powder. Then lookout, for

if they explode before reaching the ground which they generally do, the

pieces fly in all directions—the very least of which will kill one

and most of them of sufficient weight to team through a house from top

to bottom! The parrot shells come directly so one can feel somewhat

protected from them by getting under a wall, but when both come at once

and so fast that one has not time to see where one shell is going before

another comes—it wears one out."

|

A VICKSBURG MANSION BEING USED BY THE U.S. SIGNAL CORPS. (LC)

|

|

Grant used McPherson's and Sherman's corps to converge on Jackson

from two directions. On May 13, McPherson's corps marched for Clinton,

located a few miles north of Raymond and west of Jackson. At Clinton,

McPherson turned east. Sherman's XV Corps moved northeast from Raymond

on the Raymond-Jackson road. McClernand's XIII Corps waited in reserve,

having been ordered by Grant to withdraw from probing along Bakers

Creek just east of Edwards. McClernand's job was to keep Pemberton's

army away from the two Union corps attacking Jackson.

Joseph Johnston arrived in Jackson the same day Grant's forces left

Raymond. Jefferson Davis had decided that Yankee successes in

Mississippi called for Johnston's presence. Johnston was not

enthusiastic about taking command, and when he arrived he concluded, "I

am too late." He observed inadequate entrenchments around Jackson and

decided at once to evacuate the city. Reinforcements were rapidly moving

toward Jackson, and had Johnston decided to stay and fight he would have

had at least enough men to hold Grant off until Pemberton could move

forward and hit the Federal rear.

|

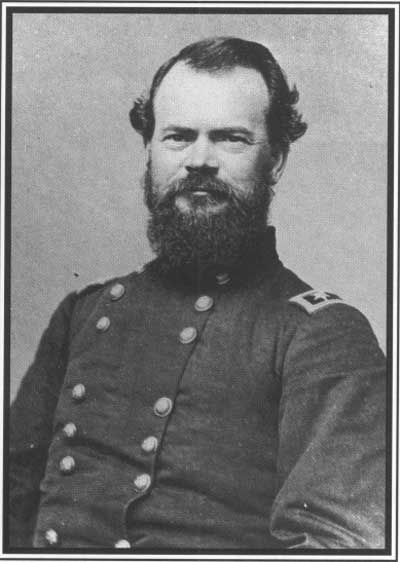

MAJOR GENERAL JAMES B. MCPHERSON (NA)

|

|

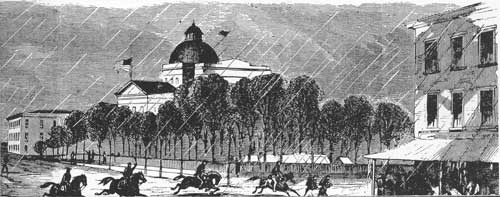

A THEODORE DAVIS ILLUSTRATION OF THE STARS AND STRIPES FLYING OVER

JACKSON, MISSISSIPPI (LC)

|

Johnston did not even know Grant's intentions at the time he made the

decision to retreat. But the stoic Johnston usually preferred

retreating to fighting, so he ordered John Gregg to hold out until

supplies and state records had been evacuated and then to bring the

four brigades defending the city to Canton, northeast of Jackson. Gregg,

after his encounter with McPherson at Raymond, gladly obliged, putting

up resistance ranging from token to slight in most sectors of the

Confederate defenses when the Yankees began their assault on May 14.

Sporadic artillery duels, charges, feints, and heavy rain

characterized the Battle of Jackson, which was really more a Confederate

holding action than an all-out fight. Rain during the morning hours

slowed the Yankee attack. Downpours turned roads into ribbons of mud,

making the moving of artillery difficult. Before noon the front passed

through, but the rain had given the Rebels more time to evacuate.

On the southern flank of the Confederate line, Sherman's forces took

advantage of the clearing weather by attacking the Rebel left. They

found empty trenches and unobstructed passage to the state capitol

building. On McPherson's front west of town, the Confederates put up

stiffer resistance, but the results were the same. Several Rebel

sacrificial lambs, left behind to contain the Federals as long as

possible, surrendered to McPherson's corps. Grant had taken Jackson with

less than 300 casualties while Confederate losses were estimated at

about 900. With Johnston's army out of the picture, Grant could now turn

to Pemberton.

Thanks largely to his skill and daring, thus far the campaign since

crossing the Mississippi had gone Grant's way. His diversions had kept

Rebel forces scattered, thus preventing a concentration that could have

left Grant outnumbered. Because he had moved rapidly and had kept

Pemberton guessing, Grant had had superior battlefield numbers at Port

Gibson, Raymond, and Jackson. His good fortune continued now as he

focused on the Confederates waiting near the Big Black.

|

|