|

In November 1862, President Davis gave Johnston the Department of the

West, which encompassed a huge portion of the Confederacy between the

Mississippi River on the west and Virginia, the Carolinas, and Florida

on the east. Johnston was not pleased, for he considered his command too

vast for coordinated military movements. He was also disturbed that his

two immediate subordinates, Pemberton and Major General Braxton Bragg

(Bragg commanded the Confederate Army of Tennessee), continued to report

directly to the War Department in Richmond rather than channeling their

correspondence through him. Johnston was further discouraged that his

suggested strategy of concentrating Confederate forces in the western

theater was rejected by the Davis government. In short, Joe Johnston was

not in a positive frame of mind as the Vicksburg campaign developed.

On October 20, McClernand received secret orders allowing him to

organize volunteer troops in the Midwest for an amphibious operation

against Vicksburg.

|

Union General John McClernand was very positive about what he wanted

to do. He wanted an independent command, to capture Vicksburg, and thus

to obtain glory and a major boost to his future political aspirations.

He blamed the incompetence of professional soldiers for the fact that

the Mississippi River was still partially closed. McClernand sought and

won permission from Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and President

Lincoln to raise a volunteer army to hammer into submission the

"insignificant garrison" defending the river fortress. On October 20,

McClernand received secret orders allowing him to organize volunteer

troops in the Midwest for an amphibious operation against Vicksburg. He

did not know that Henry Halleck, who opposed McClernand's self-serving

plans, would work to undermine the expedition. As fast as McClernand and

his lieutenants organized companies and regiments, Halleck gave them

immediate assignments in the Vicksburg theater to get them out of

McClernand's reach.

|

GENERAL JOSEPH E. JOHNSON (USAMHI)

|

U. S. Grant eventually got wind of what was amiss and worked to speed

up his own plans for attacking Vicksburg. Grant began assembling an

invading force at Grand Junction, Tennessee, where the Mississippi

Central Railroad, which offered an inviting route of invasion into the

heart of Mississippi, intersected the Memphis and Charleston line, which

connected Memphis and Corinth. Grant had in mind a converging operation

with two Federal wings invading Mississippi. One wing would be led by

Cump Sherman from Memphis, the other by Grant from Grand Junction. Grant

initially targeted Holly Springs, some twenty-five miles below Grand

Junction, and even Grenada, another eighty-five miles south-southwest

of Holly Springs.

In early November, Grant ordered out patrols and waited for reinforcements.

Conflicting intelligence reports and Confederate resistance

thwarted Grant's efforts to get his grand movement southward under way.

He was still uneasy about McClernand, but Halleck assured Grant that he

had authority "to fight the enemy where you please." Grant gave Sherman

the go-ahead to march three divisions from Memphis to Oxford or the

Tallahatchie River and an eventual junction with Grant's wing. Grant

meanwhile was besieged with supply problems and Confederate cavalry

raids as he attempted to mobilize his wing.

Finally in late November, the Federal thrust got under way. The blue

wave of the Union XIII Corps swept southward, occupying Holly Springs

and pushing on to the Tallahatchie. On December 1, outnumbered

Confederate forces evacuated their Tallahatchie entrenchments and began

pulling back to Grenada. General Pemberton really had no choice because,

in addition to the Sherman-Grant invasion, Federal troops in Helena,

Arkansas, located on the west bank of the Mississippi below Memphis,

had been ordered to proceed across the river and strike eastward toward

the Tallahatchie in the direction of Grenada. With his flank and rear

threatened, Pemberton had to rush his army southward. Soon the

Confederates would be dug in behind the Yalobusha River at Grenada.

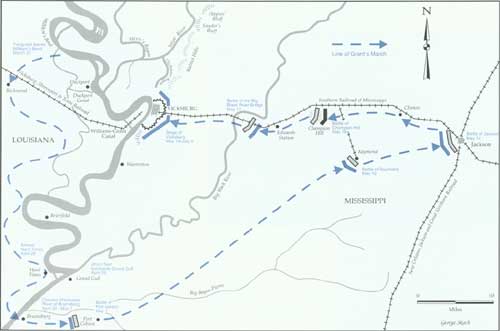

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

GRANT'S FINAL CAMPAIGN AGAINST VICKSBURG

Grant prepares to cross into Mississippi at Grand Gulf, but after a

battle with Confederate guns Porter moves downstream to Bruinsburg.

Grant soon has John McClernand's corps in Mississippi, followed by James

McPherson's. On May 1, Grant's army wins the Battle of Port Gibson.

Victories come at Raymond, Jackson, Champion Hill, and the Big Black

River. Grant is ready to begin a direct assault on Vicksburg. After two

unsuccessful assaults, Grant decides on siege tactics and after 47 days,

Confederate commander John Pemberton surrenders on July 4.

|

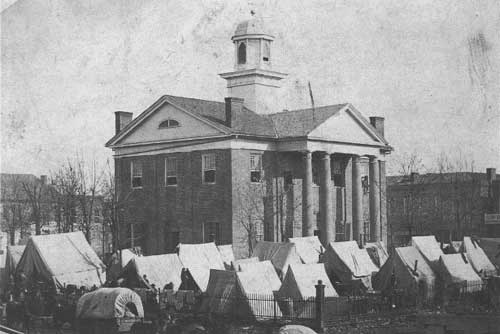

The retreat had created consternation among civilians. In Oxford,

"columns of [Confederate] troops, tired, wet and soiled, poured through

the town, accompanied by carriages, buggies, and even carts, filled

with terror-stricken, delicate ladies—whole families carrying with

them their household goods and negroes."

Logistical problems and severe skirmishing forced Grant to halt at

Oxford, where he consolidated his gains. The expedition from Helena

returned to its point of origin after the Confederates abandoned the

Tallahatchie line. Grant sent troops out to repair the Mississippi

Central and bridges damaged by retreating Rebels. Union troops also

busily stored supplies at Holly Springs, while Grant reorganized the

army for an advance on Grenada.

Sometime during the course of the campaign to this point, Grant

decided to send Sherman and one division back to Memphis where Cump was

to organize an amphibious expedition against Vicksburg while Grant kept

Pemberton pinned down in north Mississippi. Grant was concerned about

extending his tenuous supply line beyond the Grenada front and no doubt

was still anxious to take Vicksburg before McClernand arrived. So he

ordered Sherman to move down the Mississippi, land in the area where the

Yazoo River emptied into the Mississippi just above Vicksburg, cut all

the railroads supplying the city, and begin siege operations.

|

A UNION CAMP AT THE OXFORD, MISSISSIPPI, COURTHOUSE. (CHICAGO HISTORICAL

SOCIETY)

|

|

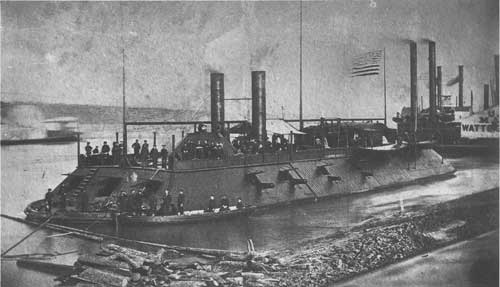

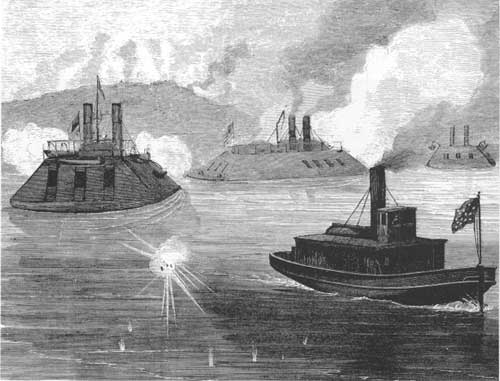

THE TINCLAD RATTLER SPENT HER CAREER AS A RAIDER ON THE

MISSISSIPPI AND YAZOO RIVERS. (U.S. NAVAL HISTORICAL CENTER)

|

Sherman organized an impressive force. His expeditionary army

included four infantry divisions composed of ten brigades and several

batteries totaling fifty-four guns, plus more than two brigades of

cavalry. Sherman's total strength was about 40,000. He also had the

promised help of the Union navy. On December 20, Federal transports

began ferrying Sherman's men downriver. Morale was high, as Union

soldiers belted out refrains of "John Brown's Body" and "Yankee Doodle"

and argued about whether they would have Christmas dinner in

Vicksburg.

Confederate cavalry, meanwhile, had U. S. Grant looking nervously

over his shoulder. To help ease the Union pressure on Pemberton,

Confederate General Braxton Bragg ordered Brigadier General Nathan

Bedford Forrest to raid Grant's supply line between Columbus, Kentucky,

and north Mississippi. Forrest and his men carried out their assignment

with much elan and skill, destroying bridges, stations, and supplies. On

December 31 at Parker's Cross Roads in Tennessee, Forrest suffered a

rare defeat and lost much of his booty. Nevertheless, Forrest had gotten

Grant's attention, and the latter soon changed his base from Kentucky to

Memphis.

|

MAJOR GENERAL EARL VAN DORN (NA)

|

|

MAJOR GENERAL STERLING PRICE (NA)

|

On the Grenada front, one of Pemberton's colonels suggested a raid on

Grant's ever-growing supply base at Holly Springs. Pemberton agreed and

gave the orders; success might stop any further Yankee advance and

perhaps could even force Grant to order a retreat. On December 18, Earl

Van Dorn led about 3,500 Confederate horsemen into the Union rear and

two days later took the Holly Springs depot completely by surprise. Van

Dorn estimated that his raid resulted in the destruction of $1.5 million

worth of supplies. He then continued northward up the Mississippi

Central before escaping back to Grenada. The assaults of Forrest and Van

Dorn did indeed force Grant to pull his army back to Memphis.

Van Dorn seemed to have at last found his niche as leader of

Pemberton's cavalry. Unfortunately for Van Dorn, his days of leading

glorious cavalry charges were numbered; he would be killed by an

allegedly jealous husband in May of 1863. Pemberton also was about to

lose a corps commander, Sterling Price. Price wanted to return to his

native Missouri and carry Missouri troops with him, but Pemberton was

much too impressed with the Missourians to let them go. Richmond

supported Pemberton's decision, and Price departed, leaving his beloved

troops behind. A third major general, Mansfield Lovell, soon left

Mississippi, never to return to the war. Lovell, the scapegoat of the

Confederacy's loss of New Orleans, had been unable to regain the

confidence of Davis. John Bowen, Carter Stevenson, and William Loring

would eventually replace the three lost commanders.

Grant's retreat seemingly gave Pemberton more time to focus on

organizational problems. But any sense of security vanished when Pemberton

learned of Sherman's move down the Mississippi. Pemberton had felt that

his Vicksburg flank was secure ever since Union gunboats steaming up the

Yazoo had withdrawn. The fleet had been scared off after the USS

Cairo had hit a torpedo (a mine planted in the river by the

Rebels) and sunk. A few days before Christmas, Pemberton was

entertaining President Davis and Joseph Johnston on the Grenada front

when he received word of Sherman's presence near Vicksburg.

|

THE USS CAIRO WAS SUNK BY A TORPEDO. ITS REMAINS ARE ON EXHIBIT

AT VICKSBURG NATIONAL MILITARY PARK. (LC)

|

Pemberton alerted his various commanders to be ready at a moment's

notice to reinforce Martin Smith's Vicksburg garrison. Meanwhile, he

arranged for his distinguished guests, who had recently come to

Mississippi and inspected the Vicksburg defenses and were now consulting

on strategic matters with Pemberton, to review the troops.

Ominous telegrams from Vicksburg continued to pour in, so Pemberton

cut the review short, ordered more reinforcements for Smith, and

entrained for Vicksburg. Davis soon left for Richmond, while Johnston

settled in temporarily at Pemberton's Jackson headquarters.

Sherman's army landed and marched toward the Walnut Hills north and

northeast of Vicksburg. Aware that Grant had retreated, Sherman decided

to attack anyway on December 27, initiating the Battle of Chickasaw

Bayou. To defend Vicksburg, General Smith had three divisions and

several batteries of heavy artillery; he had about half Sherman's

strength but the advantage of well-fortified high ground. A provisional

division led by Stephen D. Lee and Carter Stevenson's division bore the

brunt of the Union attack.

On December 29, Sherman had to admit defeat. Several of his brigades

had been decimated in fruitless assaults. John DeCourcy's and Frank

Blair, Jr.'s brigades totaled 1,315 casualties. Sherman loaded his

battered army back on transports and returned to Memphis. Pemberton had

used his interior lines well, shifting troops to a threatened point and

winning a great victory. For the moment, Vicksburg was safe.

|

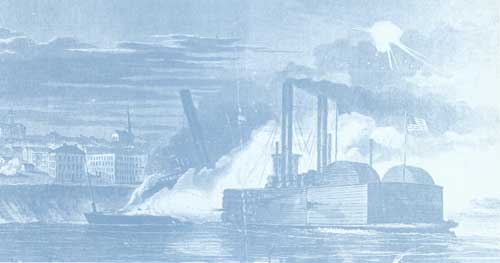

SHERMAN'S TROOPS ARE SHOWN STORMING CHICKASAW BAYOU IN THIS PERIOD

ENGRAVING. (FRANK AND MARIE WOOD PRINT COLLECTION)

|

|

FEDERAL GUNBOATS BOMBARD FORT HINDMAN. (LC)

|

Grant had been thwarted in the first round of his attempt to capture

Vicksburg, but his diversion in north Mississippi while Sherman tried an

end run set the tone for the remainder of the campaign. Grant continued

to use diversion upon diversion, and Pemberton kept guessing as to his

opponent's intentions.

While Grant pondered his next move, John McClernand arrived on the

scene and, by reason of seniority in rank, took command of Sherman's

expeditionary force. With two Union corps, the XIII and XV, and several

Union gunboats, McClernand attacked Arkansas Post (Fort Hindman), a

Confederate fortress some fifty miles up the Arkansas River from where

it emptied into the Mississippi. The campaign lasted from January 4 to

12, 1863, resulting in the fall of Fort Hindman. No longer could

Confederate gunboats use the Arkansas as a refuge from which to launch

attacks on Union shipping. Nevertheless, Grant was not happy at

McClernand's independent foray and ordered this intruder to get his

forces ready for future, coordinated operations against Vicksburg.

Grant intended to remain on the offensive. One of his initial steps

in January of 1863 was a renewed attempt to build a bypass canal at

DeSoto Point, the peninsula around which the Mississippi River looped in

front of Vicksburg. By digging a canal across the base of the peninsula,

Grant hoped to divert river traffic away from Confederate shore batteries.

Thomas Williams had tried the same strategy in 1862, but low

water and disease among the troops had defeated the plan. Grant's

attempt also failed, mainly and ironically because of high water, but at

least he kept some of his troops active and improved their physical

condition for the rigors of the coming spring campaign.

Next came the Lake Providence expedition. Grant's engineers thought

the lake, crescent-shaped and located some 75 river miles above

Vicksburg on the Louisiana side of the Mississippi, might provide access

to a network of streams that could give Federal shipping a path to the

Red River, which emptied into the Mississippi below Vicksburg. If the

idea worked, Grant could get troops safely south of the Confederate

fortress, reinforce Nathaniel Banks's Federal army then operating

against Port Hudson, and then take his and Banks's troops north to

assault Vicksburg. It all sounded fine in theory, but in practice

numerous problems arose and the expedition was called off.

Nevertheless, the flooding caused by Union engineers during the

operation later helped to secure Grant's flank when he later marched his

army down the west side of the Mississippi.

|

AN ILLUSTRATION OF THE INDIANOLA RUNNING THE BLOCKADE AT

VICKSBURG. (LC)

|

|

THE QUEEN OF THE WEST FIRES AT THE CONFEDERATES' CITY OF

VICKSBURG. THE QUEEN OF THE WEST WOULD LATER BE CAPTURED BY THE

CONFEDERATES. (COURTESY MISSISSIPPI DEPT. OF ARCHIVES AND HISTORY)

|

Federal fortunes on the river itself were not very positive in the

early winter months of 1863. The Union gunboat USS Indianola

successfully steamed southward past the Vicksburg batteries in

February. The Indianola took a position at the mouth of the Red

River to attack Confederate shipping. A few days later, Confederate

gunboats, including the Queen of the West, captured earlier by

the Confederates, rammed and partially sank the Indianola,

forcing its surrender. The Yankees burned another boat, the

DeSoto, to prevent its capture.

Losses and failed expeditions did not deter Grant. He next planned an

expedition through Yazoo Pass, a bayou on the east side of the

Mississippi just south of Helena, Arkansas. Union engineers blasted a

man-made levee to open the way to the Coldwater River via the pass. From

the Coldwater troop transports could follow a potential route to the

Yazoo via the Tallahatchie. If everything worked, Grant could land

troops downriver at Yazoo City and have a short land route to

Vicksburg.

Everything did not work. Confederates in force waited for the Yankee

expedition at Fort Pemberton, located near where the Tallahatchie and

the Yalobusha come together to form the Yazoo at Greenwood, Mississippi.

The Rebels, commanded by William Loring, pounded the Union forces May

11-16, forcing yet another of Grant's detachments to give up an

expedition.

Despite the victory, Fort Pemberton proved to be a seedbed of

discontent for the Confederate high command. Loring harassed Pemberton

for reinforcements and more artillery, neither of which Pemberton had to

spare. Pemberton questioned Loring's ability to make good use of extra

men and guns even if he had them in the restricted confines of Fort

Pemberton. The exchanges led to an open break between the two generals,

especially on Loring's part. Loring allied himself with Lloyd Tilghman,

a former friend of Pemberton's, who harbored anger at the commanding

general over an incident involving unauthorized destruction of army

property in north Mississippi. Tilghman had been arrested and later

cleared, but he had not forgotten. Pemberton's problems with these two

officers did not bode well for the future.

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL LLOYD TILGHMAN (NA)

|

|

REAR ADMIRAL DAVID D. PORTER (USAMHI)

|

The Federals, meanwhile, continued to have problems, having to

abandon another ongoing canal project. The so-called Duckport canal on

the Louisiana side of the Mississippi west of Vicksburg was to pass

through several bayous and enter the river well south of the Vicksburg

defenses. Low water and other problems finally doomed the canal.

Another amphibious operation also failed. David Porter led an

expedition up Steele's Bayou in hopes of gaining the Sunflower River,

which emptied into the Yazoo above Vicksburg. Once in the Yazoo, the

expedition would be in a position to operate against Vicksburg or go

upstream to assist in the campaign against Fort Pemberton. But thanks to

Rebel obstructions, Porter's fleet got bogged down and had to be rescued

by a detachment rushed forward by Sherman. The Steele's Bayou operation

was canceled.

Whether Grant ever expected any of his failed plans to work is

debatable. He surely would have been pleased had one succeeded, but it

seems likely that his intent was to remain active enough to keep

politicians off his back, to keep his men active and in good spirits,

and to keep Pemberton guessing. All the winter operations had the effect

of diversions, since they kept Pemberton looking anxiously in several

different directions. Pemberton had realized that he simply did not

have the manpower to checkmate all the possibilities available to

Grant. Thus far, weather, geography, and determined defensive stands at

the right places had worked in favor of the Confederates. But if

Pemberton ever guessed wrong, his mistake could be fatal.

Grant hoped that he had created enough anxiety to make the Rebel

commander guess wrong. But he intended to leave nothing to chance. He

continued his strategy of diversion while inaugurating the third,

decisive, phase of the Vicksburg campaign.

|

UNION TROOPS UNDER THE COMMAND OF COLONEL BENJAMIN GRIERSON CAMP AT

BATON ROUGE IN MAY 1863. (ANDREW D. LYTLE COLLECTION, LOUISIANA STATE

UNIVERSITY)

|

On March 29, U. S. Grant made a decision. Rejecting the ideas of a

frontal assault on Vicksburg or returning to north Mississippi to start

a new campaign, he chose to march his army down the west side of the

Mississippi to a point below Vicksburg where river transports would

ferry the men across. The transports would have to run the gauntlet of

the Vicksburg batteries, but other vessels had done so; in any event it

was a gamble worth taking.

To improve his chances for success, Grant resorted to his favorite

strategy of diversions.

|

To improve his chances for success, Grant resorted to his favorite

strategy of diversions. In early April he sent a detachment commanded

by Frederick Steele to Greenville, Mississippi, where the Federals moved

inland and operated along Deer Creek, destroying Confederate supplies

and trying to convince Pemberton that the Vicksburg target had been

abandoned in favor of operations upriver.

Several Federal steamers returning north toward Memphis

unintentionally gave Pemberton the idea that Grant had given up and was

pulling back. Actually Grant had ordered several boats away from the

Vicksburg front to relieve traffic congestion on the Mississippi.

Pemberton's misreading of the situation indicated that perhaps Grant's

luck was changing.

Grant's most spectacular, and most successful, diversion was a Union

cavalry raid that originated in LaGrange, Tennessee, on April 17,

slashed through the heart of Mississippi, and ended safely in Baton

Rouge, Louisiana, on May 2. The leader of the raid was an unlikely hero.

Thirty-seven-year-old Colonel Benjamin Henry Grierson had been a music

teacher and businessman in Illinois before the war. The man whose name

would become synonymous with the famous 1863 cavalry raid that

contributed to the fall of Vicksburg also did not like horses.

Despite his unlikely qualifications Grierson had a knack for cavalry

tactics. Adopting his own diversionary strategy, Grierson led his 1,700

riders sweeping through Mississippi on a general diagonal route from

northeast to southwest, sending out detachments here and there all

along the way. The result confused Pemberton's already unreliable

intelligence network. The Yankees seemed to be everywhere at once, and

the unreliability of Confederate communications left Pemberton in a

quandary as he tried to coordinate his forces to intercept Grierson.

|

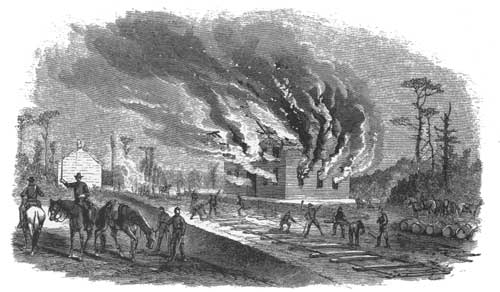

A RAILROAD STATION IN MISSISSIPPI IS DESTROYED BY GRIERSON'S RAIDERS.

(FRANK AND MARIE WOOD PRINT COLLECTION)

|

Pemberton was handicapped by a shortage of cavalry, having earlier

lost Van Dorn's horseman to Braxton Bragg. Confederate cavalry should

have been concentrated, but political circumstances forced Pemberton to

use his cavalry to defend as much of north Mississippi as possible. The

result was that at one point, Pemberton had to use infantry in a failed

attempt to catch Grierson in central Mississippi.

Grierson lost only 15 men during the raid and 5 of those had to be

left along the way owing to illness. He claimed to have captured over

3,000 stand of arms, destroyed 50-60 miles of railroad track as

well as tons of Confederate property, and captured 1,000 horses and

mules that the Rebels could ill afford to lose. Sherman correctly called

Grierson's raid "the most brilliant expedition of the war."

Grant unleashed other raids to tie down Pemberton's limited cavalry

resources. In northeast Mississippi and north Alabama Union cavalry

threatened Braxton Bragg's supply line and Pemberton's communication

artery, the Southern Railroad of Mississippi. The most spectacular

incident of these operations was the pursuit and capture of Union

Colonel Abel Streight's cavalry column in north Alabama by Brigadier

General Nathan Bedford Forrest.

But by May 3, when Forrest bagged Streight's raiders, whose mission

had been planned in coordination with Grierson's, Grant had won a major

battle and had established a strong foothold in Mississippi below

Vicksburg. Streight had at least succeeded in keeping Forrest from

helping Pemberton.

While Steele, Grierson, Streight, and others helped mask Grant's

grand design, John Bowen worried about increased Yankee activity below

Vicksburg on the Louisiana side of the Mississippi. Bowen commanded at

Grand Gulf, Mississippi, a river town several miles below Vicksburg,

where high bluffs had been well fortified with Confederate cannon.

Pemberton told Bowen that any serious Yankee advance could be contested

but that the Grand Gulf defenses must be kept secure. The commanding

general then dismissed Bowen's concerns: "I do not regard it of such

importance as to risk your capture."

|

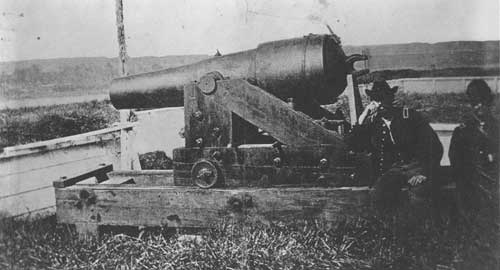

CONFEDERATE CANNON LIKE THIS 32-POUNDER BROOKE RIFLE WREAKED HAVOC ON

THE FEDERAL FLEET. IT IS SHOWN HERE IN FEDERAL HANDS. (LC)

|

|

J. O. DAVIDSON'S PAINTING OF PORTER PASSING THE VICKSBURG BATTERIES.

(AMERICAN HERITAGE PICTURE COLLECTION)

|

Next day Pemberton reported to Richmond the rumors that a division of

John McClernand's XIII Corps was moving down the west side of the river,

rumors which he doubted. Pemberton made a fatal mistake when he doubted;

it was not just a division but McClernand's corps that was on the move

in Louisiana.

In those early April days, before Grierson's raid, Pemberton

concluded that Federal forces were "constantly in motion in all

directions." Yet that knowledge did not deter him from ignoring Bowen

and concluding that Grant was indeed giving up the fight. Pemberton,

deluding himself into a sense of security, felt so confident that he

offered to send reinforcements from his army to Bragg's Army of

Tennessee. Joseph Johnston cautioned Pemberton against such a rash

decision and suggested that troops be sent to points of departure where

they could be shuffled as needed.

|

ON APRIL 29 ADMIRAL PORTER'S GUNBOATS BOMBARDED THE CONFEDERATES AT

GRAND GULF. (BL)

|

By the middle of April, Pemberton began to change his mind. He

received a message from Bowen that accurately predicted Grant's true

intentions—ferrying the Federal army across the river into

Mississippi. Union forces would then march northward and attack

Vicksburg. Other reports indicated Federal gunboat activity around a

stream called Bayou Pierre, which emptied into the Mississippi below

Grand Gulf, and that Union transports, heavily loaded with infantry,

were steaming southward toward Vicksburg. Then came news on April 17

that several southbound, empty enemy vessels had successfully run the

gauntlet of the Vicksburg batteries. Pemberton immediately wired

Johnston that no more troops could be sent to Bragg and that those en

route should be sent back to Vicksburg. Johnston agreed.

Just as Pemberton was getting a grasp on the situation facing him,

Grierson and his cavalry rode out of Tennessee into Mississippi creating

the vital diversion that Grant desired. For two weeks as April faded and

May approached, Pemberton kept his eyes on Grierson while Grant

continued to march his men southward for the crossing below Vicksburg.

Pemberton, who was much better at dealing with the known than with the

suspected, turned his attention away from the real threat at his back

door.

After Grierson escaped into south Mississippi, Sherman demonstrated

against the Snyder's Bluff area north of Vicksburg, turning Pemberton's

attention once again in the wrong direction. Sherman's mission was a

diversion from Grand Gulf, where Union gunboats were about to launch an

attack. Grant hoped to knock out Rebel batteries and ferry his troops

into Mississippi at that point. The diversion was not successful, but

Sherman had given Pemberton more to think about.

On April 29, eight Union gunboats shelled Grand Gulf for six hours,

but the Rebels commanded by John Bowen refused to yield their position.

Bowen was a tenacious fighter and his defenders, including his division

of Missourians and Arkansans, reflected the character of their

commander. Eight large-caliber cannon emplaced in Forts Cobun and Wade

anchored Bowen's defense. Confederate fire from these forts inflicted

heavy casualties on three Yankee gunboats: USS Benton, USS

Tuscumbia, and the USS Pittsburg. All but one of the 75

Union dead and wounded were hit on those vessels. By comparison, Bowen

lost 3 killed and 19 wounded. Grant would have to go farther down the

Mississippi to find a crossing.

He initially looked downstream at Rodney, a small river town south of

Grand Gulf, connected by road to Port Gibson. The town of Port Gibson

lay inland a few miles and would provide a good staging area for Grant

to assemble his forces and move north toward Vicksburg. When Grant's

scouts learned that a road also led from Bruinsburg, located between

Rodney and Grand Gulf, into Port Gibson, Grant changed his orders.

|

MAJOR GENERAL ANDREW J. SMITH (BL)

|

|

THE UNION FLEET AT GRAND GULF FIRED ON THE CONFEDERATE ARTILLERY TO

PREPARE FOR THE CROSSING OF TROOPS BELOW VICKSBURG. (LC)

|

On April 30, 1863, Union boats began ferrying the 17,000 troops of

the XIII Corps across the Mississippi from Disharoon's Plantation in

Louisiana to Bruinsburg. At the time, this was the largest amphibious

operation in American history. Most of the corps had waded ashore in

Mississippi by early afternoon.

Around 4 P.M., the XIII began marching toward Port Gibson. The corps

included the divisions of Peter Osterhaus, A. J. Smith, A. P. Hovey, and

Eugene Carr. Despite the lateness of the hour, McClernand urged his

troops forward. He feared that the Rebels, surely alerted by now, might

destroy the bridges across Bayou Pierre at Port Gibson, thus delaying

the Union advance and giving Pemberton more time to concentrate his

forces.

Soon the column of bluecoats saw Windsor, the landmark, palatial

home of a wealthy Mississippi planter, as they marched along the

Bruinsburg-Port Gibson road before turning right onto a trail that

connected with the Rodney-Port Gibson road. The decision to veer

off the Bruinsburg road was based on a fear that the Confederates

probably had blocked the road near Port Gibson. Also, the Rodney road

ran closely parallel to the Bruinsburg route and would not cost much

time.

In the hills west of Port Gibson, the landscape became treacherous.

Steep ravines bordered high ridges. If the Federals encountered

Confederate opposition, the men would have to deploy on either side of

the road, which, in rugged terrain, at night, would indeed be a

challenge.

But the invaders were in high spirits. An Illinois sergeant noted

that the "moon is shining above us and the road is romantic in the

extreme." Yet he admitted that the geography of narrow valleys and steep

hills presented the Rebels a grand opportunity for defense "if they had

but known our purpose." Little did he know that a showdown lay ahead as

the Union column swung east onto the Rodney-Port Gibson road.

Meanwhile, back at the Bruinsburg beachhead, Union boats began

ferrying John Logan's division of James McPherson's XVII Corps across

the river. Logan's presence gave Grant some 25,000 soldiers immediately

available in case the Confederates contested the inland march.

|

MAGNOLIA CHURCH ON THE PORT GIBSON BATTLEFIELD CIRCA 1938. (PHOTO BY

MARGIE BEARSS)

|

He had consistently warned Pemberton about what was going on, but

all his warnings and dire predictions had fallen on deaf ears.

|

A frustrated John Bowen knew Grant's intentions, indeed had suspected

them for some time. He had consistently warned Pemberton about what was

going on, but all his warnings and dire predictions had fallen on deaf

ears. When Union vessels moved southward away from Grand Gulf, Bowen had

no doubt that the enemy would attempt to cross the Mississippi beyond

the range of Grand Gulf cannon. Bowen needed reinforcements

desperately. If Grant indeed landed in force south of Bayou Pierre,

there were not enough Confederate forces on hand to keep him there and

certainly not enough to drive him back to the river. Also, if Grant

established his army on the east side of the Mississippi, Bowen would

have no choice but to abandon Grand Gulf, which would be vulnerable to

attack from the flank and rear.

While he waited for troops from Vicksburg, Bowen hurried a detachment

under Martin Green to Port Gibson to set up roadblocks west of the town

near where roads from Rodney and Bruinsburg converged. Ultimately, based

on scouting reports, Bowen decided to send forces down both roads. He

had received incorrect information that the Union column marching

toward Port Gibson had divided, one detachment coming up the Rodney

road, while a separate column had remained on the Bruinsburg road.

Green's force moved down the Rodney road to a good defensive position

near Magnolia Church just east of the A. K. Shaifer house. A recently

arrived Alabama brigade from Vicksburg, commanded by Edward Tracy, moved

west down the Bruinsburg road in search of the Yankees on that route.

William Baldwin's brigade of Louisiana and Mississippi troops hurried

toward Port Gibson from Vicksburg. Pemberton hastily ordered other units

to the coming fight, but they would not arrive in time.

Reports of Union gunboats moving from the Mississippi River into

Bayou Pierre jerked Bowen's attention away from approaching Federal

ground troops. He moved more batteries to the river and also ordered

guns to the Big Black River, which ascended from the Mississippi north

of the Port Gibson area on a northeasterly course into central

Mississippi. Bowen recognized that the Union navy could capture the

Bayou Pierre bridges and cut off his force from any further

reinforcements from Vicksburg and from the Missouri brigade still at

Grand Gulf. The fate of Bowen's command and Port Gibson would be decided

on land, however, not on water.

As the night of April 30 passed slowly near Magnolia Church, Martin

Green grew impatient. At 12:30 A.M., May 1, he mounted a horse and rode

toward the Shaifer house to check on his skirmish line. News of the

impending battle had reached female occupants of the house, who

scurried back and forth loading family belongings on a wagon for escape

to Port Gibson. Green rode forward to reassure them that the enemy was

not close yet. At that moment shots rang out, striking the house and the

wagon. An advance Federal patrol had arrived and opened fire. The women,

including Mrs. Shaifer, decided they had loaded enough and jumped in the

wagon, heading for Confederate lines.

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL EUGENE A. CARR (LC)

|

|

COLONEL FRANCIS M. COCKRELL (LC)

|

Green's Confederates tensed up and waited while Yankee regiments

deployed in the ravines to the west. Union artillery sent shot, shell,

and canister roaring through the countryside, echoing eerily among the

hills and gullies where the battle of Port Gibson would be decided.

Night engagements in the Civil War were rare, and the soldiers would not

soon forget this one. The fighting waned when General Eugene Carr

decided to wait until morning before continuing the Federal

deployment.

|

|