|

MAY 10: GRANT ASSAULTS LEE'S LINE

Grant planned a massive assault at five o'clock in the afternoon

across Lee's entire line in hopes of overwhelming the Confederates. The

scheme began to unravel around 2:00 P.M., when Hancock returned to the

Po to help extricate Barlow. Hancock's departure left Warren in charge

of the Laurel Hill sector. The Fifth Corps commander was still smarting

from earlier reverses and was anxious to redeem his reputation. As soon

as Hancock left, he petitioned Meade for permission to attack Laurel

Hill right away, unsupported and before the scheduled five o'clock

advance. For reasons that have never been explained, Meade consented to

Warren's request.

At about 4:00 P. M., Warren led elements from the Second and Fifth

Corps against Laurel Hill. A witness summarized the results. "Some

portions of the corps advanced to the abatis, others halted part way

and discharged a few volleys, but speedily the whole line fell back with

terrible loss." A few units elbowed through smoldering cedars only to

become mired in a freshly plowed field. "How we got through it all I

don't know," a Union survivor reminisced.

|

IN ITS RETREAT TO THE PO RIVER, ONE GUN OF CAPTAIN WILLIAM A. ARNOLD'S

BATTERY A, FIRST RHODE ISLAND LIGHT ARTILLERY, BECAME WEDGED BETWEEN TWO

TREES AND HAD TO BE ABANDONED. IT WAS THE FIRST GUN EVER LOST BY THE

SECOND CORPS. (FROM WARREN GOSS, RECOLLECTIONS OF A PRIVATE)

|

Grant had no choice but to postpone the grand assault until Warren

could reconstitute his formation. Word of the delay, however, apparently

never reached Brigadier General Gershom Mott, and at 5:00 P.M. he

charged alone toward the tip of the Confederate salient. "On reaching

the open field," one of his officers reported, "the enemy opened his

batteries, enfilading our lines and causing our men to fall back in

confusion."

|

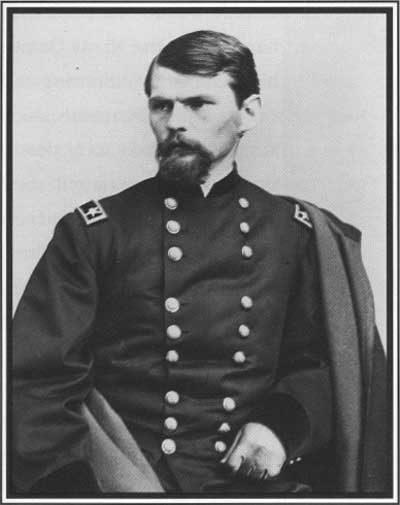

JUST 29 YEARS OLD IN 1864, FRANCIS BARLOW LOOKED MORE LIKE "A HIGHLY

INDEPENDENT MOUNTED NEWSBOY" THAN A MAJOR GENERAL. HANCOCK WOULD SELECT

HIM TO LEAD THE MAY 12 ASSAULT ON THE MULESHOE. (BL)

|

|

WAITING TO ATTACK

In his efforts to find a weak spot in Lee's defenses, Grant ordered a

series of attacks against the Confederate line on May 10. By far the

most successful of these ventures was an attack led by Colonel Emory

Upton of the Sixth Corps. Just before sundown, Upton led 5,000 men in a

charge against the western face of the Muleshoe salient, overrunning

the Confederate line and taking some 1,000 prisoners. The 121st New

York Volunteers, a regiment Upton had commanded earlier in the war, was

in the first line of battle. Clinton Beckwith, an officer in the

regiment, described the tension in the ranks as the time of attack

approached.

|

CONFEDERATE SOLDIERS CAPTURED IN UPTON'S ATTACK WERE RUN BACK INTO UNION

LINES NEAR THE SHELTON HOUSE. FROM THERE, THEY WENT TO POINT LOOKOUT,

MARYLAND, AND OTHER PRISON CAMPS IN THE NORTH. (LC)

|

"About 5 P.M. we moved over the works down into the woods, close up

to our skirmishers (the 65th N.Y.), who were keeping up a rapid fire,

and formed in line of battle. Regiment after regiment came up and formed

in line, we being in the first or front line and the right of the column

. . . . The Rebel rifle pits were about two hundred and fifty yards in

front of our skirmish line. They had no skirmishers out, ours having

driven them in, but they were firing from their breastworks, on top of

which they had logs to protect their heads. Our batteries (one on the

right and three in the rear of us) were belching away at them, and they

were answering but feebly. Occasionally the hum of a bullet and the

screech of a shell gave notice that they were on the qui vive.

As soon as we were formed Colonel Upton, Major Galpin and the

Adjutant came along and showed to the officers and men a sketch of just

how the Rebel works were located, and we were directed to keep to the

right of the road which ran from our line direct to theirs . . . . We

were ordered to fix bayonets, to load and cap our guns and to charge at

a right shoulder shift arms. No man was to stop and succor or assist a

wounded comrade. We must go as far as possible, and when we broke their

line, face to our right, advance and fire lengthwise of their line.

Colonel Upton was with our regiment and rode on our right. He instructed

us not to fire a shot, cheer or yell, until we struck the works. It was

nearly sundown when we were ready to go forward. The day had been bright

and it-was warm but the air felt damp, indicating rain. The racket and

smoke made by the skirmishers and batteries, made it look hazy about us,

and we had to raise our voices to be heard. We waited in suspense for

some time. Dorr Davenport, with whom I tented, said to me, 'I feel as

though I was going to get hit. If I do, you get my things and send them

home.' I said, 'I will, and you do the same for me in case I am shot,

but keep a stiff upper lip. We may get through all right.' He said, 'I

dread the first volley, they have so good a shot at us.' Shortly after

this the batteries stopped firing, and in a few minutes an officer rode

along toward the right as fast as he could, and a moment afterward word

was passed along to get ready, then 'Fall in,' and then 'Forward.' I

felt my gorge rise, and my stomach and intestines shrink together in a

knot, and a thousand things rushed through my mind. I fully realized

the terrible peril I was to encounter. I looked about in the faces of

the boys around me, and they told the tale of expected death. Pulling my

cap down over my eyes, I stepped out. . . ."

|

Sometime after six o'clock, the Sixth Corps launched its phase of the

attack, led by Colonel Emory Upton and a select force of twelve

regiments. Upton quietly assembled his troops at the edge of the woods

across from the salient's western leg and instructed them to charge

without pausing to fire or load. His front line was to breach the works

and then spread right and left along the Rebel trenches, widening the

cleft, and his remaining units were to consolidate the gains.

|

RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE SIXTH CORPS' MAY 10 ATTACK ON THE MULESHOE FELL

TO TWENTY-FOUR-YEAR-OLD EMORY UPTON. (LC)

|

A volley spewed from the Rebel works, then another. Gaps appeared

in Upton's formation, but the men kept on, clawing through the abatis

and over the entrenchments.

|

Union artillery pounded the Rebel works in front of Upton, then fell

silent. "Forward!" sounded the command. "I felt my gorge rise, and my

stomach and intestines shrink together in a knot, and a thousand things

rushed through my mind," a Northerner recounted. Upton's blue-clad host

swept across the field. A volley spewed from the Rebel works, then

another. Gaps appeared in Upton's formation, but the men kept on,

clawing through the abatis and over the entrenchments.

At first, the plan went like clockwork. After rupturing the

works, Upton's Federals splayed along the trenches in each direction,

virtually annihilating Brigadier General George P. Doles's Georgians.

Lee and Ewell feverishly organized a counterattack. Daniel's brigade

plugged the trenches below Doles, Brigadier General James A. Walker's

Stonewall Brigade held firm to the north, and Brigadier General George

H. "Maryland" Steuart's brigade sprinted over from the salient's far

side. Then Battle's Alabamians and Brigadier General Robert D.

Johnston's North Carolinians dove in, along with Colonel Clement A.

Evans's Georgians. Within minutes, Upton's men had been battered back

and driven to seek shelter against the outer face of the earthworks.

|

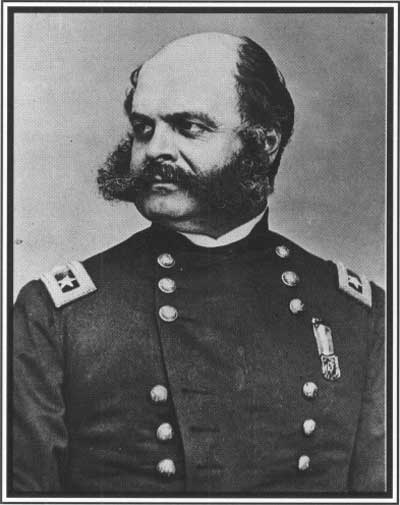

ONCE THE ARMY OF THE POTOMAC'S COMMANDER, AMBROSE BURNSIDE RETURNED TO

VIRGINIA IN 1864 AS HEAD OF THE INDEPENDENT NINTH CORPS. HIS TIMID

ATTACKS AT WILDERNESS AND SPOTSYLVANIA LOST HIM GRANT'S CONFIDENCE AND

ULTIMATELY LED TO HIS REPLACEMENT. (LC)

|

Upton cast about in vain for the support that he had been promised.

Mott, however, had already been repulsed, and Warren's soldiers were too

jaded from their earlier attacks against Laurel Hill to help. A few

Second and Fifth Corps units ventured into the Spindle fields and

momentarily breached Anderson's lines, but their gains were fleeting.

"Fruitless as the first," a Federal called the attack. As darkness

fell, Upton ordered his men back. "Bitter were the reproaches to which

both Russell and Upton gave utterance when upon Upton's return he gained

shelter of the woods," a Northerner recounted. "I sat down in the

woods," a soldier wrote, "and as I thought of the desolation and misery

about me, my feelings overcame me and I cried like a little child."

Although Grant did not realize it, his best opportunity for success

on May 10 lay in front of Burnside. Lee had weakened his eastern flank

by sending Mahone and Heth to the Po. During the afternoon, a single

Confederate division—Cadmus Wilcox's—guarded the Fredericksburg

Road, and a yawning gap separated Wilcox from Ewell in the salient.

With Sheridan off on his raid, Grant was deprived of his "eyes and

ears" and hence missed the opportunity that he had been seeking.

Burnside advanced timidly along the Fredericksburg Road around six

o'clock, met determined resistance from Wilcox, and decided to entrench

a quarter of a mile from the hamlet. Headquarters then fretted that

Burnside was too far advanced and ordered him back to the Ni. As Grant

conceded in his memoirs, withdrawing Burnside "lost to us an important

advantage." Even Burnside's soldiers were perplexed. "It was a profound

mystery to the men in the ranks, at the time, why such a movement should

have been made," a Northerner wrote.

But Grant remained optimistic as ever. Upton had failed, but perhaps

the attack held an important lesson. Lee's works were not invulnerable.

They could be breached if the attackers moved quickly, without pausing

to fire and reload. Upton had failed because he had lacked proper

support. What if an attack were launched similar to Upton's with an

entire corps? And what if the supporting troops consisted of the rest of

the Union army? Here, Grant concluded, lay the key to destroying

Lee.

|

|