|

MAY 6: LONGSTREET SAVES THE DAY

At 5:00 A.M., the Union attack rumbled up the plank road just as

Grant had planned. Hill's soldiers faced an overwhelming force in front

with more Federals storming in from the north. The rebel Third Corps

collapsed, and gray-clad troops streamed for the rear. "It looked as if

things were past mending," a Confederate admitted.

Lee had ordered Lieutenant Colonel William T. Poague's artillery to

form above the plank road at Widow Tapp's farm. Poague's gunners fought

valiantly to stem the blue-clad tide erupting from the far woods. Hill,

who had once served in the artillery, helped work the guns. But the

last-ditch effort was doomed. A few cannon, no matter how gallantly

manned, could not stave off an army. It appeared that within minutes,

the Army of Northern Virginia would be in shambles.

|

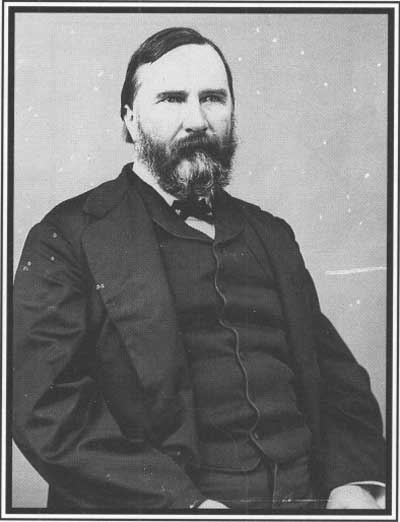

THE ARRIVAL OF JAMES LONGSTREET'S CORPS CHECKED HANCOCK'S ADVANCE AND

SAVED LEE'S SUPPLY TRAINS. "LIKE A FINE LADY AT A PARTY, LONGSTREET WAS

OFTEN LATE IN HIS ARRIVAL AT THE BALL," WROTE A CONFEDERATE ARTILLERIST,

"BUT HE ALWAYS MADE A SENSATION AND THAT OF DELIGHT, WHEN HE GOT IN."

(LC)

|

Suddenly gray-clad troops pounded up the plank road from Lee's rear.

"General, what brigade is this?" Lee inquired of an officer. "The Texan

brigade," came the answer, which told Lee that Longstreet had arrived at

last. He jerked his hat from his head and shouted, "Texans always move

them!" Under the moment's excitement, Lee began advancing with the

foremost troops. When the men realized that Lee was with them, they

stopped and refused to budge until he went to the rear. At a staffer's

urging, Lee finally consented to ride to the rear and speak with

Longstreet, who by now had arrived on the field. Longstreet persuaded

Lee that he had matters well in hand, and the Confederate army

commander retired behind the battle front.

Longstreet's soldiers counterattacked, Major General Charles W.

Field's division above the plank road and Brigadier General Joseph B.

Kershaw's below. The Federals had become disordered during their advance

and were in no shape to resist Longstreet's impetuous assault. Within an

hour, Longstreet had driven Hancock back several hundred yards east of

the Tapp clearing.

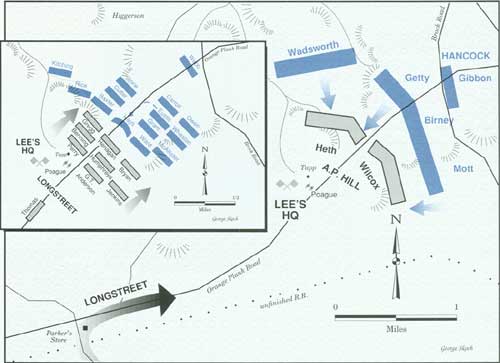

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

HANCOCK ROUTS HILL'S CORPS: MAY 6, 5 A.M.

At dawn, Hancock renews his attacks on Hill's corps, driving it in

confusion toward the Tapp Field. Confederate artillery briefly checks

Hancock's advance, and when Longstreet's corps arrives, Lee is able to

push Hancock back toward the Brock Road (inset).

|

The rest of Grant's well-laid scheme quickly unraveled. Burnside,

whose Ninth Corps was supposed to maneuver against Hill's flank, instead

fell several hours behind schedule and was finally stymied by Brigadier

General Stephen D. Ramseur's Confederate brigade. Realizing that

Burnside had failed in his mission, Grant ordered him to cut south

through the thickets and join Hancock. Burnside's advance was so delayed

that he remained unavailable to the Union war effort until after most of

the important fighting had finished.

Lee remained anxious to retain the initiative. Around 10:00 A.M., his

chief engineer, Major General Martin L. Smith, explored an unfinished

railroad grade and discovered that it afforded access to the lower Union

flank. Longstreet's aide G. Moxley Sorrel and Brigadier General William

Mahone led several brigades along the unfinished grade to a point

opposite Hancock's left flank. At eleven o'clock, Sorrel's men struck.

As Hancock later conceded, the Rebels rolled up his line "like a wet

blanket." At the same time, more of Longstreet's troops attacked along

the plank road and drove Hancock just as Hill had been driven a few

hours before. Wadsworth was mortally wounded, and Hancock's wing retired

to Brock Road.

|

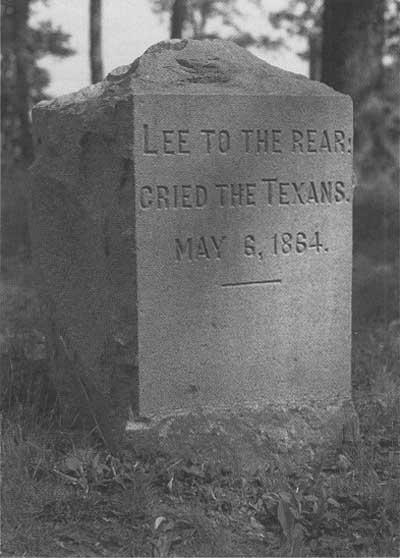

"TEXANS ALWAYS MOVE THEM"

Among the most thrilling episodes of the Civil War occurred on May 6, 1864, in

the Wilderness. At dawn, Union troops led by Major General Winfield S.

Hancock attacked and routed A. P. Hill's corps on the Orange Plank Road.

Lee and Hill tried desperately to rally the defeated Confederates as

they came streaming back to the rear, but few men heeded their cries.

Just as disaster seemed inevitable, Lieutenant General James

Longstreet's First Corps arrived on the field. Longstreet's men opened

ranks to let Hill's men through, then charged Hancock's men, slowly

driving them back toward the Brock Road. Spearheading the attack north

of the road was Brigadier General John Gregg's Texas Brigade. As the

Texans moved forward, General Lee rode beside them, intent on leading

the charge. His men would have none of it. In a scene that would be

repeated no less than five times in the next week, the Confederates

compelled Lee to go to the rear. A Texan, who identified himself only as

"R. C." was witness to this dramatic event.

"The cannon thundered, musketry rolled, stragglers were fleeing,

couriers riding here and there in post-haste, minnies began to sing, the

dying and wounded were jolted by the flying ambulances, and filling the

road-side, adding to the excitement the terror of death . . . . About

this time, Gen. Lee, with his staff, rode up to Gen. Gregg—'General

what brigade is this?' said Lee. 'The Texas brigade,' was General G's.

reply. 'I am glad to see it,' said Lee. 'When you go in there, I wish

you to give those men cold steel—they will stand and fire all day,

and never move unless you charge them,' 'That is my experience,' replied

the brave Gregg. By this time an aide from General Longstreet rode up

and repeated the order, 'advance your command, Gen. Gregg.' And now

comes the point upon which the interest of this 'o'er true tale' hangs.

'Attention Texas Brigade' was rung upon the morning air, by Gen. Gregg,

'the eyes of General Lee are upon you, forward, march.' Scarce had we

moved a step, when Gen. Lee, in front of the whole command, raised

himself in his stirrups, uncovered his grey hairs, and with an earnest,

yet anxious voice, exclaimed above the din and confusion of the hour,

'Texans always move them.' . . . A yell rent the air that must have been

heard for miles around . . . . Leonard Gee, a courier to Gen. Gregg, and

riding by my side, with tears coursing down his cheeks and yells issuing

from his throat exclaimed, 'I would charge hell itself for that old

man.' It was not what Gen. Lee said that so infused and excited the men,

as his tone and look, which each one of us knew were born of the dangers

of the hour.

With yell after yell we moved forward, passed the brow of the hill,

and moved down the declivity towards the undergrowth—a distance in

all not exceeding 200 yards. After moving over half the ground we all

saw that Gen. Lee was following us into battle—care and anxiety

upon his countenance—refusing to come back at the request and

advice of his staff. If I recollect correctly, the brigade halted when

they discovered Gen. Lee's intention, and all eyes were turned upon him.

Five and six of his staff would gather around him, seize him, his arms,

his horse's reins, but he shook them off and moved forward. Thus did he

continue until just before we reached the undergrowth, not, however,

until the balls began to fill and whistle through the air. Seeing that

we would do all that men could do to retrieve the misfortunes of the

hour, accepting the advice of his staff, and hearkening to the protest

of his advancing soldiers, he at last turned round and rode back."

|

AT WILDERNESS AND AGAIN AT SPOTSYLVANIA LEE ATTEMPTED TO LEAD HIS TROOPS

INTO BATTLE. EACH TIME, HIS SOLDIERS SHOUTED HIM BACK. (NPS)

|

|

As his Rebels began clearing the plank road of the enemy, a

triumphant Longstreet rode forward with several officers. Some of

Mahone's Virginians involved in the flank attack had meanwhile crossed

the plank road and were returning. They spied the headquarters

cavalcade, mistook it for Federals, and opened fire. Longstreet fell

with a severe wound through his neck, and one of his most promising

brigade commanders, Brigadier General Micah Jenkins, was killed.

Commentators later reflected on parallels between Longstreet's wounding

and the shooting of Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson. The two prominent

Confederate generals had been shot by their own men while executing

successful flanking maneuvers, and the incidents had occurred almost a

year apart and in the Wilderness. As one of Lee's aides later remarked,

"the old deacon would say that God willed it thus." Longstreet's

wounding, along with disorienting wooded terrain, stalled the attack

that Longstreet had so skillfully initiated. Lee labored to resume the

offensive but was unable to position his troops until after four

o'clock. By then, Hancock had ensconced his corps behind imposing earthworks

lining Brock Road. Lee assaulted and gained an advantage when the

works caught fire but lacked the manpower to exploit the breakthrough.

His failed attack against Hancock's Brock Road line represented the

last major offensive attempted by the Army of Northern Virginia.

|

AFTER USHERING GENERAL LEE TO SAFETY, THE TEXAS BRIGADE SWEPT ACROSS THE

TARP FIELD TO ENGAGE THE ENEMY. OF THE 800 MEN WHO MADE THE CHARGE, MORE

THAN 500 DID NOT RETURN. (NPS)

|

|

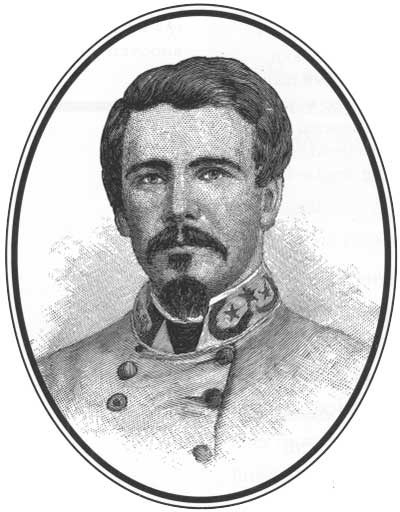

BRIGADIER GENERAL MICAH JENKINS WAS AMONG THE FIRST TO CONGRATULATE

LONGSTREET ON THE SUCCESS OF HIS FLANK ATTACK. MINUTES LATER, BULLETS

FROM A CONFEDERATE VOLLEY PIERCED JENKIN'S SKULL AND LEFT LONGSTREET

SERIOUSLY WOUNDED. (BL)

|

|

|