|

MAY 5: EWELL SURPRISES WARREN ON ORANGE TURNPIKE

Early on the morning of May 5, the Union Fifth Corps started out a

farm path toward Orange Plank Road, leaving pickets a short way out

Orange Turnpike to sound the alarm if Confederates came from that

direction. As the pickets prepared to move on, they saw a wisp of dust

on the horizon. Soon Ewell's corps appeared, marching straight toward

the enemy.

Warren sent word to Meade that Confederates were approaching. The

army commander in turn notified Grant, who directed that "if any

opportunity presents itself of pitching into a part of Lee's army, do so

without giving time for disposition." Assuming that the unexpected

gray-clad visitors constituted only a small body, Meade halted his army

and directed Warren to attack.

|

GRANT WATCHED THE FIFTH AND SIXTH CORPS ACROSS GERMANNA FORD FROM A

BLUFF OVERLOOKING THE RIVER. WHEN ASKED BY A REPORTER HOW LONG IT WOULD

TAKE HIM TO GET TO RICHMOND, GRANT REPLIED FOUR DAYS. "THAT IS, IF

GENERAL LEE BECOMES A PARTY TO THE AGREEMENT," HE ADDED, "BUT IF HE

OBJECTS THE TRIP WILL UNDOUBTEDLY BE PROLONGED." (LC)

|

The Confederates began erecting earthworks along the western edge of

a clearing known as Saunders Field. Warren advanced Brigadier General

Charles Griffin's division to the east edge of the clearing. Brigadier

General James S. Wadsworth's division formed in dense woods on Griffin's

left, and Brigadier General Samuel W. Crawford's Pennsylvania Reserves

occupied the Chewning farm knoll farther south. Warren hesitated to

attack, however, because the Confederate formation overlapped Griffin's

flank and would enfilade him if he advanced. Warren beseeched Meade to

postpone the assault until Sedgwick arrived and formed on his right. By

1:00 P.M., however, Meade had become so exasperated with Warren's delay

that he ordered him to proceed without Sedgwick. "It was afterwards a

common report in the army," an aide recounted, "that Warren had just had

unpleasant things said to him by General Meade, and that General Meade

had just heard the bravery of his army questioned."

|

THE BATTLE OPENED AT SAUNDERS FIELD, A CLEARING THAT EXTENDED ON EITHER

SIDE OF ORANGE TURNPIKE. "THE LAST CROP OF THE OLD FIELD HAD SEEN CORN,"

WROTE A MEMBER OF WARREN'S STAFF, "AND AMONG ITS STUBBLE THAT DAY WERE

SOWN THE SEEDS OF GLORY." (LC)

|

Griffin's men strode across Saunders Field into intense Confederate

firepower. Brigadier General Romeyn B. Ayres's brigade, on Griffin's

right, was blistered by Southerners shooting from behind earthworks to

the front and right. Blue-clad survivors broke across the field, many

seeking refuge in a gully. Brigadier General Joseph J. Bartlett,

advancing up the turnpike's left side, had slightly better success. His

lead units overran the Confederate line—commanded by Brigadier

General John M. Jones, who was killed—and punched forward about a

quarter of a mile. Ayres's inability to keep pace, however, left

Bartlett's rightmost flank exposed, and rebels quickly exploited the

weak point. Bartlett fled with his men and barely escaped capture when

his horse was shot from under him.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

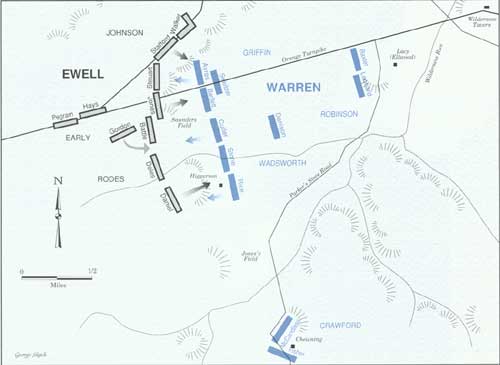

WARREN OPENS THE FIGHTING MAY 5, 1:00 P.M.

Griffin attacks Ewell across Saunders Field, supported by Wadsworth's

division south of the turnpike. The Federals succeed in rupturing the

center of Ewell's line below the road, but vigorous counterattacks by

John Gordon, Junius Daniel and others quickly restore the line. To the

south, Crawford's division maintains its hold on the Chewning firm,

while two brigades of Robinson's division remain in reserve near the

Lacy House.

|

Brigadier General Lysander Cutler's famed Iron Brigade advanced in

tandem with Bartlett through woods immediately south of Saunders Field.

Although Cutler initially made headway against Brigadier General Cullen

A. Battle's Alabamians, he was brought up short by a counterattack

launched by Brigadier General John B. Gordon. Positioned near the

turnpike, the charismatic Gordon thrust his brigade into the head of

Cutler's advance, then spread units right and left to chew their way

through the Federal formation. For the first time in its history, the

Iron Brigade broke and streamed rearward. On Cutler's left, Colonel Roy

Stone's Pennsylvanians entered dense woods bordering the Higgerson

place. They mired in a swamp—the "champion mud hole of mud holes,"

a survivor described it—while Brigadier General George Doles's

Georgians fired into them from a nearby ridge. To the left of Stone,

Brigadier General James C. Rice's brigade crossed a clearing, became

disoriented in a stand of woods, and fled as Brigadier General Junius

Daniel's North Carolinians emerged from the thickets onto its

flanks.

|

"SURRENDER OR DIE!"

The dense woods of the Wilderness made possible surprises and in many

instances fostered panic among the troops who fought there. A case in

point is the experience of Lieutenant Holman Melcher of the Twentieth

Maine Volunteers. On May 5, Warren's Fifth Corps broke Ewell's line

south of the Orange Turnpike, driving the Confederates back half a mile.

Melcher and a small body of men plunged through the break and when Ewell

successfully counterattacked, they found themselves trapped behind enemy

lines. Faced with the alternative of being sent to a Confederate prison

camp, they boldly determined to cut their way out. Melcher described the

episode in a speech delivered to the Military Order of the Loyal Legion

a quarter-century after the battle.

|

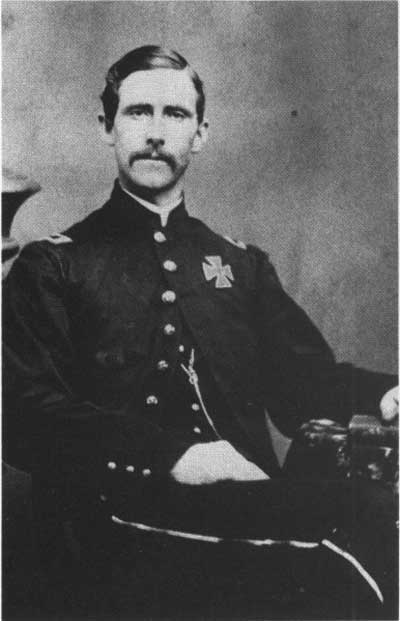

LT. HOLMAN MELCHER (COURTESY WILLIAM STYPLE)

|

"As we emerged from the woods into this field, General Bartlett, our

brigade commander, came galloping down the line from the right, waving

his sword and shouting, 'Come on, boys, let us go in and help them!' And

go we did. Pulling our hats low down over our eyes, we rushed across the

field, and overtaking those of our comrades who had survived the fearful

crossing of the front line, just as they were breaking over the enemy's

lines, we joined with them in this deadly encounter, and there in that

thicket of bushes and briers, with the groans of the dying, the shrieks

of the wounded, the terrible roar of musketry and the shouts of command

and cheers of encouragement, we swept them away before us like a

whirlwind....

The pursuit of my company and those immediately about me continued

for about half a mile, until there were no rebels in our front to be

seen or heard; and coming out into a little clearing, I thought it well

to reform my line, but found there was no line to form, or to connect it

with. I could not find my regimental colors or the regiment. There were

with me fifteen men of my company with two others of the regiment. I was

the only commissioned officer there, but my own brave and trusted first

sergeant, Ammi Smith, was at my side as always in time of danger or

battle, and with him I conferred as to what it was best to do under the

circumstances.

"There was nothing in front to fight that we could see or hear,

but to go back seemed the way for cowards to move, as we did not know

whether our colors were at the rear or farther to the front."

|

There was nothing in front to fight that we could see or hear, but to

go back seemed the way for cowards to move as we did not know whether

our colors were at the rear or farther to the front. I was twenty-two

years old at this time, and Sergeant Smith twenty-three, so that our

united ages hardly gave years enough to decide a question that seemed so

important to us at that moment . . . .

Forming our 'line of battle' (seventeen men beside myself) in single

rank, of course . . . we approached quietly and unobserved, as the

'Johnnies' were all intent on watching for the 'Yanks' in front, not for

a moment having a suspicion that they were to be attacked from the rear,

until we were within ten or fifteen paces, when on the first intimation

that we were discovered, every one of our little band picked his man and

fired, and with a great shout as much as if we were a thousand, we

rushed at them and on to them, sword and bayonets being our weapons.

'Surrender or die!' was our battle-cry.

They were so astonished and terrified by this sudden and entirely

unexpected attack and from this direction, that some of them promptly

obeyed, threw down their arms and surrendered. The desperately brave

fought us, hand to hand; the larger part broke and fled in every

direction through the woods, and could not be followed by us or our

fire, as our rifles were empty and there was no time to reload.

This was the first, and I am glad to say, the last time that I saw

the bayonet used in its most terrible and effective manner. One of my

men, only a boy, just at my side, called out to a rebel to throw down

his gun, but instead of obeying he quickly brought it to his shoulder

and snapped it in the face of this man, but fortunately it did not

explode, for some reason.

Quick as a flash, he sprang forward and plunged his bayonet into his

breast, and throwing him backward pinned him to the ground, with the

very positive remark, 'I'll teach you, old Reb, how to snap your gun in

my face!' And this was only one scene of many such I saw enacted around

me, in that terrible struggle. How I wished my sword had been ground to

the sharpness of a razor, but the point was keen and I used [it] to the

full strength of my arm.

I saw a tall, lank rebel, only a few paces from me, about to fire at

one of my men and I the only one that could help him. I sprang forward

and struck him with all my strength, intending to split his head open,

but so anxious was I that my blow should fall on him before he could

fire that I struck before I got near enough for the sword to fall upon

his head, but the point cut the scalp on the back of his head and split

his coat all the way down his back. The blow hurt and startled him so

much that he dropped his musket without firing and surrendered, and we

marched him out with the other prisoners.

In less time than it has taken me to tell this we had scattered the

line of battle and the way was open for us to escape. Two of our little

band lay dead on the ground where we had fought, and several more or

less severely wounded, but these latter we kept with us and saved them

from capture. By spreading our little company out rather thin we were

able to surround the thirty-two prisoners we had captured in the melee

and started them along on the double quick, or as near to it as we could

and keep the wounded along with us.

The Confederate line soon began to rally and fired after us; but as

there were many more of the Gray than the Blue in our ranks, they

hesitated to do much firing, as they saw they would be more likely to kill

friends than foes."

|

As the Union formation dissolved, Crawford began hurrying his

division back. One regiment—the Seventh Pennsylvania—became

separated and was captured by a handful of Gordon's Georgians under

Major Frank Van Valkenberg. Under cover of the dense woods, the Georgia

major was able to make his squad appear as though it were a regiment. "I

never saw a group of more mortified men," a Southerner remarked of the

Pennsylvanians' reaction on discovering they had been tricked into

surrendering to a vastly inferior force.

|

AT 1:00 P.M., THE FEDERALS ATTACKED. THE 140TH NEW YORK VOLUNTEERS, A

ZOUAVE REGIMENT, LED THE ASSAULT NORTH OF THE TURNPIKE. (COURTESY KEITH

ROCCO)

|

|

THE HIGGERSON FARM STOOD DIRECTLY IN THE PATH OF COL. ROY STONE'S MAY 5

ADVANCE. MRS. HIGGERSON SCOLDED STONE'S MEN FOR TRAMPLING HER GARDEN AND

PREDICTED THEIR SPEEDY REPULSE. "WE DIDN'T PAY MUCH ATTENTION TO WHAT

SHE SAID," ADMITTED ONE SOLDIER, "BUT THE RESULT PROVED THAT SHE WAS

RIGHT." (NPS)

|

A participant described the battle in the deep woods as a "weird,

uncanny contest—a battle of invisibles with invisibles." Another

recounted that "men's faces were sweaty black from biting cartridges,

and a sort of grim ferocity seemed to be creeping into the actions and

appearance of everyone within the limited range of vision."

|

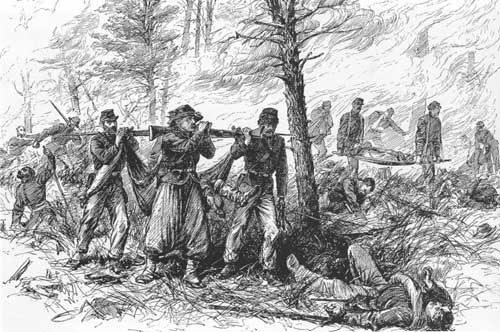

BRUSH FIRES SWEPT ACROSS SAUNDERS FIELD, DEVOURING ALL WHO STOOD IN

THEIR PATH. SOME WOUNDED SOLDIERS WERE CARRIED TO SAFETY; OTHERS WERE

BURNED ALIVE. (BL)

|

Warren thrust an artillery section into Saunders Field, which began

lobbing shells into friend and foe. When the Federals came tumbling

back, Rebels swarmed into the field and captured the guns. Warren's

riflemen, however, prevented them from hauling off the pieces. "'Twas

claw for claw, and the devil take us all" a Southerner recounted of the

vicious hand-to-hand combat. Then the field caught fire. Wounded men

tried to crawl to safety, and soldiers from both armies watched in

horror as their compatriots were consumed in flames. Finally, under cover

of darkness, Rebels dragged the artillery pieces into their lines.

|

FISTFIGHT IN SAUNDERS FIELD

In the confused swirl of combat at Saunders Field, the fighting

sometimes took on a peculiarly personal tone. John Worsham of the

Twenty-first Virginia Infantry described one such encounter in his

book, One of Jackson's Foot Cavalry.

"Running midway across the little field was a gully that had been

washed by the rains. In their retreat many of the enemy went into this

gully for protection from our fire. When we advanced to it, we ordered

them out and to the rear. All came out except one, who had hidden under

an overhanging bank and was overlooked. When we fell back across the

field, the Yankees who followed us to the edge of the woods shot at us

as we crossed. One of our men, thinking the fire too warm, dropped into

the gully for protection. Now there was a Yankee and a Confederate in

the gully—and each was ignorant of the presence of the other!

After awhile they commenced to move about in the gully, there being

no danger so long as they did not show themselves. Soon they came in

view of each other, and they commenced to banter. Then they decided that

they would go into the road and have a regular fist and skull fight, the

best man to have the other as his prisoner. While both sides were

firing, the two men came into the road about midway between the lines of

battle, and in full view of both sides around the field. They surely

created a commotion, because both sides ceased firing! When the two men

took off their coats and commenced to fight with their fists, a yell

went up along each line, and men rushed to the edge of the opening for a

better view! The 'Johnny' soon had the 'Yank' down; the Yank

surrendered, and both quietly rolled into the gully. Here they remained

until nightfall, when the 'Johnny' brought the Yankee into our line. In

the meantime, the disappearance of the two men into the gully was the

signal for the resumption of firing. Such is war!"

|

A MODERN VIEW OF SAUNDERS FIELD LOOKING EAST FROM EWELL'S LINE. (NPS)

|

|

At 2:45, Griffin strode up to Meade and Grant. He loudly announced

that he had driven Ewell back three-quarters of a mile but that Sedgwick

had failed to arrive and Wadsworth had been repulsed, leaving both his

flanks exposed. "Who is this General Gregg? You ought to arrest him,"

Grant told Meade after the angry subordinate had stomped out. Meade

reached over and began buttoning Grant's jacket, as though Grant were a

little boy. "It's Griffin, not Gregg," Meade answered, "and it's only

his way of talking."

Around 3:00 P.M., Sedgwick's lead elements reached Saunders Field. By

then, fighting had sputtered to a close. A new battle erupted, however,

as Sedgwick tried to overrun Ewell's line in the woods above the

turnpike. Fighting seesawed as each side made fierce but inconclusive

charges. Brigadier General Leroy A. Stafford, heading a Louisiana

brigade, fell when a bullet severed his spine. His brigade was repulsed,

as was the famed Stonewall Brigade, but the determined Louisianian waved

reinforcements into battle as he lay writhing in agony. After an hour of

confused and bloody combat, Sedgwick's and Ewell's warriors disengaged

and began erecting earthworks. Fighting continued throughout the

evening—Brigadier General John Pegram was severely wounded during

an attack against his Virginia brigade—but neither side could claim

advantage. Ewell had executed his assignment to perfection and stymied

two Union corps.

|

JOHN SEDGWICK COMMANDED THE SIXTH CORPS IN THE WILDERNESS. "HIS WHOLE

MANNER BREATHED OF GENTLENESS AND SWEETNESS," WROTE ONE SOLDIER. "HIS

SOLDIERS CALLED HIM UNCLE JOHN, AND IN HIS BROAD BREAST WAS A BOY'S

HEART." (NA)

|

|

|