|

MAY 11: GRANT PREPARES FOR THE GRAND ASSAULT

During the morning of May 11, Grant matured his plans. He decided to

spear-head the attack with the Second Corps and ordered Hancock to the

Brown house, where Mort had launched his charge on the tenth. From

there, Hancock was to assault the Confederate salient's tip shortly

before daylight on the twelfth. At the same time, Burnside was to attack

the salient's eastern leg, and Warren and Wright were to keep the

Confederates on Laurel Hill pinned in place. One of Meade's aides

summarized the scheme as a "repetition of Mott's attack on the 10th, on a

much larger scale in every way."

|

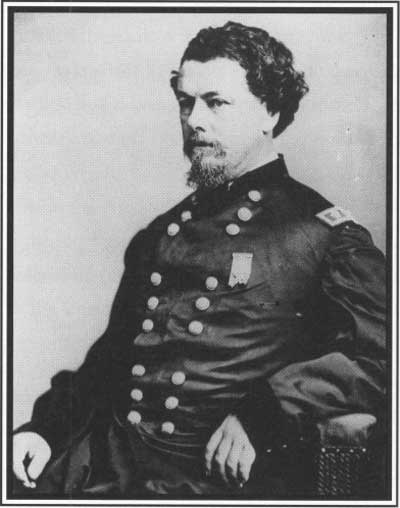

MAJOR GENERAL HORATIO G. WRIGHT COMMAND OF THE UNION SIXTH CORPS

SEDGWICK'S DEATH ON MAY 9.

|

As the day progressed, Lee received intelligence that Grant might be

planning to retire toward Fredericksburg. The Confederate commander

wanted to be ready to strike immediately and directed his corps

commanders to prepare to march on short notice. He was concerned,

however, that artillery in the salient might have difficulty pulling out

and hence slow the army's response. According to one of Lee's aides,

"orders were given to withdraw the artillery from the salient occupied

by Major General Edward "Allegheny" Johnson's division to have it

available for a countermove to the right." Little did Lee suspect that

he was weakening the very place that Grant intended to attack.

In the afternoon, rain began falling in torrents. "The wind was

raw and sharp," a Federal wrote, "our clothing wet, and we were just

about as disconsolate and miserable a set of men as were ever

seen."

|

In the afternoon, rain began falling in torrents. "The wind was raw

and sharp," a Federal wrote, "our clothing wet, and we were just about

as disconsolate and miserable a set of men as were ever seen."

After dark, Hancock's corps began shifting to the Brown house. The

march was a miserable affair. Soldiers sloshed behind one another and

tried to follow their file leader "not by sight or touch, but by hearing

him growl and swear, as he slipped, splashed, and tried to pull his

'pontoons' out of the mud." The situation at the Brown house was

discouraging. No one seemed to know where the Confederates were or how

their line was oriented. Barlow, whose division was to lead the assault,

inquired, "What is the nature of the ground over which I have to pass?"

He was told, "We do not know." He asked, "What obstructions am I to

meet, if any?" only to be told, "We do not know." Exasperated, he

demanded, "Have I a gulch a thousand feet deep to cross?" The answer

came back. "We do not know." According to one account, an officer drew

a rough map on the Brown house wall to show Hancock how to face his

troops.

|

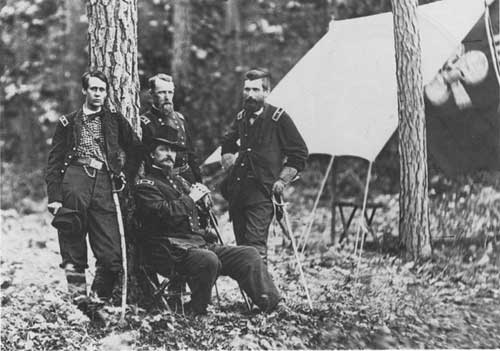

WINFIELD HANCOCK (SEATED) AND HIS DIVISION COMMANDERS FRANCIS BARLOW,

DAVID BIRNEY, AND JOHN GIBBON. (LC)

|

Lee's pickets heard sounds—a "subdued roar or noise, plainly

audible in the still, heavy night air like distant falling water or

machinery"—but were uncertain whether the Federals were leaving or

preparing to attack.

|

The Second Corps assembled behind Mott's pickets along a compass line

drawn from the Brown place to the McCoull house. Barlow's division

packed tightly into two lines, Birney on Barlow's right, Mott and Gibbon

behind. "We thus formed a huge sledge hammer," one of Barlow's officers

explained, "of which our division was the head and Birney's the handle,"

with the remainder of the corps in support. Across the way, Lee's

pickets heard sounds—a "subdued roar or noise, plainly audible in

the still, heavy night air like distant falling water or

machinery"—but were uncertain whether the Federals were leaving or

preparing to attack. By midnight, "Allegheny" Johnson, whose division

occupied the tip of the salient, concluded that mischief was afoot and

dispatched an aide to Ewell asking that the artillery be returned. Ewell

rebuffed the staffer, so Johnson visited Ewell himself. The corps

commander was persuaded by Johnson's entreaties and ordered the guns

returned. His instructions, however, were inexplicably delayed and

failed to reach the artillerists until 3:30 A.M. Rebel gunners ran to

their horses and began hauling their pieces through mud toward the

salient.

|

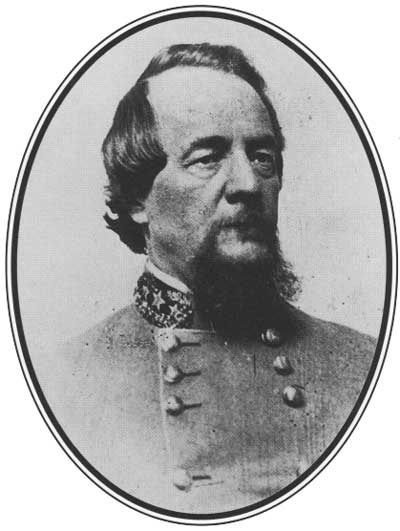

AS UNION SOLDIERS SWARMED OVER THE LOGWORKS, EDWARD JOHNSON (ABOVE)

SWUNG AT THEM WITH HIS WALKING STICK UNTIL HE WAS SURROUNDED AND FORCED

TO SURRENDER. (NA)

|

Four o'clock arrived. It was still pitch black, so Hancock postponed

the assault for another half hour. A soldier recalled that the men,

"surrounded by the silence of night, by darkness and fog, stood listening

to the raindrops as they fell from leaf to leaf." At 4:30, the rain

stopped and was replaced by a swirling, clinging mist. "Forward!" came

the command, and twenty thousand blue-clad soldiers heaved forward.

Over the Rebel picket line they pushed and onto a shallow ridge. The

sight ahead was daunting. "The red earth of a well defined line of works

loomed up through the mists on the crest of another ridge, distant about

two hundred yards with a shallow ravine between," a Northerner

recounted. Scarcely pausing, they dashed into the ravine and up the far

side, clawing through abatis. "All line and formation was now lost," a

participant recalled, "and the great mass of men, with a rush like a

cyclone, sprang upon the entrenchments and swarmed over."

|

IN A MATTER OF MINUTES, HANCOCK'S CORPS OVERPOWERED JOHNSON'S DIVISION

AND HAD GAINED THE SALIENT'S OUTER WORKS. THREE THOUSAND CONFEDERATE

PRISONERS AND TWENTY GUNS FELL INTO UNION HANDS. (COURTESY OF THE

SEVENTH REGIMENT FUND, INC.)

|

|

|