|

THE BATTLE OF CHANCELLORSVILLE

May 1863 opened in a burst of spring glory along the Rappahannock

River. Blossoms from apple, peach, and cherry trees splashed color

against a background of soft green woods. Wildflowers dotted hillsides

and ditches alongside rolling fields of luxuriant grasses and wheat half

a foot high. Nature thus masked the scars inflicted by two huge armies

over the previous months, providing a beautiful stage across which a

whirlwind of action would be played out during May's first week. Armed

with an excellent strategic blueprint, Union Major General Joseph Hooker

and his Army of the Potomac marched into this scene of pastoral renewal.

General Robert E. Lee and Lieutenant General Thomas J. "Stonewall"

Jackson reacted with a series of maneuvers that carried their fabled

collaboration to its dazzling apogee. The confrontation produced a grand

drama filled with memorable scenes, a vivid contrast in personalities

between the respective army commanders, and clogged fighting by soldiers

on both sides. Its final act brought humiliating defeat for the proud

Army of the Potomac and problemactical victory for the Army of Northern

Virginia.

|

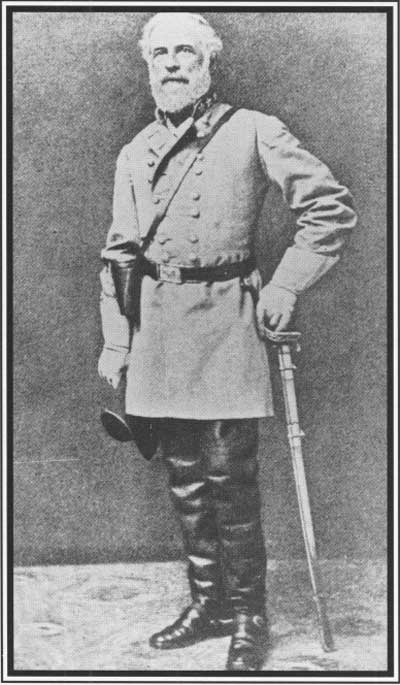

IN 1862, ROBERT E. LEE HAD DEFEATED GEORGE B. MCCLELLAN, JOHN POPE, AND

AMBROSE BURNSIDE, BUT COULD HE DEFEAT JOE HOOKER? (NPS)

|

The spring of 1863 marked the advent of the third year in an

increasingly bloody war. Along the Mississippi River, Major General

Ulysses S. Grant continued his movement against the Confederate

stronghold at Vicksburg with an eye toward establishing Union control of

the "Father of Waters." In Middle Tennessee, Major General William S.

Rosecrans and the Army of the Cumberland prepared to engage General

Braxton Bragg's Confederate Army of Tennessee in operations that could

settle the fate of Chattanooga and the Georgia hinterlands. The last

major military arena lay in Virginia, where the armies of Hooker and Lee

were arrayed along the Rappahannock River.

Neither government considered Virginia the most important theater.

President Abraham Lincoln and Major General Henry W. Halleck, his

general in chief, considered Grant's operations most important. Success

there would separate the Trans-Mississippi states from the rest of the

Confederacy, allow Northern vessels to cruise the river at will, and

provide water-borne access to great stretches of Confederate territory.

Lincoln and Halleck saw Rosecrans's movements as second in importance,

judging Hooker's activities a clear third. On the Confederate side,

Jefferson Davis and many of his generals believed the decisive fighting

would come in Tennessee. A group that has come to be known as the

"Western Concentration Bloc," which included officers such as General

Joseph F. Johnston and Lieutenant General James Longstreet as well as

Senator Louis T. Wigfall of Texas and other influential politicians,

argued that Lee's army should be weakened to reinforce Braxton Bragg's

Army of Tennessee. Lee thought otherwise and hoped to keep as much

strength as possible under his command. Mulling over the strategic

situation in late February, he had postulated victory for the

Confederacy through "systematic success" on the battlefield that would

create "a revolution among [the Northern] people."

|

AS THE CAMPAIGN OPENED, JOE HOOKER BRIMMED WITH SELF-CONFIDENCE. "MY

PLANS ARE PERFECT," HE TOLD A GROUP OF OFFICERS, "AND WHEN I START TO

CARRY THEM OUT, MAY GOD HAVE MERCY ON GENERAL LEE, FOR I WILL HAVE

NONE." (LC)

|

Lee knew better than most that military success in Virginia stood the

best chance of triggering such a revolution. Accused then and later of

wearing Virginia blinders, the Southern commander in fact understood

that the psychological power of his victories probably outweighed

whatever the Confederacy might accomplish elsewhere. The eastern theater

contained the respective capitals, each nation's largest army, and the

Confederacy's most famous generals, Lee and Jackson. The Mississippi

River or Middle Tennessee might be more crucial in a strictly military

sense, but many citizens and politicians North and South, as well as

virtually all foreign observers, considered the eastern theater to be

transcendent. Lincoln had learned this lesson the previous year, when a

series of Union victories in the West had been overshadowed by Major

General George B. McClellan's failure during the Seven Days' battles.

"It seems unreasonable," the frustrated president had observed, "that a

series of successes, extending through half-a-year, and clearing more

than a hundred thousand square miles of country, should help us so

little, while a single half-defeat should hurt us so much." The campaign

between Hooker and Lee—the one man new to army leadership and the

other a consummate field commander—would have great significance

because so many people considered it the war's centerpiece in the spring

of 1863.

|

CHANCELLORSVILLE WAS A LARGE BRICK HOUSE IN THE WILDERNESS, RATHER THAN

A TOWN AS ITS NAME MIGHT IMPLY. ORIGINALLY OPERATED AS A TAVERN, IT

BECAME HOOKER'S HEADQUARTERS DURING THE BATTLE. (BL)

|

|

A PHOTOGRAPHER TOOK THIS PICTURE OF STONEWALL JACKSON AT THE YERBY HOUSE

JUST DAYS BEFORE THE CAMPAIGN OPENED. JACKSON'S SOLDIERS LIKED THE

IMAGE, BUT HIS WIFE, ANNA, THOUGHT IT MADE HIM LOOK TOO STERN. (NA)

|

The rival commanders and their armies offered a study in contrasts on

the eve of the campaign. Hooker had been named to head the Army of the

Potomac on January 25, 1863, through a combination of solid service and

effective political maneuvering. A graduate of West Point, who ranked

twenty-ninth in the class of 1837, he had left the army in the 1850s but

accepted a brigadier generalcy of volunteers shortly after war erupted

in 1861. He missed the battle of First Bull Run, then fought as a

division and corps chief at the Seven Days, Second Bull Run, Antietam,

and Fredericksburg. A press report of action on the Peninsula headed

"Fighting-Joe Hooker" had been rendered "Fighting Joe Hooker" when it

appeared in print, thus fastening on its subject a nickname that he

despised but never managed to shake. Still, he did stand out as an

aggressive officer in an army blessed with too little of that commodity.

A shameless self promoter, Hooker worked tirelessly to supplant Major

General Ambrose F. Burnside following the Union fiasco at Fredericksburg

and the equally ignominious Mud March of mid-January 1863. Telling

Republicans in Congress what they wanted to hear, touting his own

accomplishments, and criticizing Burnside, he emerged in late January as

the president's choice to lead the Army of the Potomac.

Hooker looked the part of a general and exuded self-assurance. Above

medium height, blue-eyed, with light hair and a ruddy complexion, he cut

a dashing figure on or off a horse. "It is no vanity in me to say I am a

damned sight better general than any you had on that field," he had told

Lincoln after First Bull Run. Newspapers generally liked Hooker's

cockiness. One rhapsodized about him in January 1863 as "a General of

the heroic stamp.... who feels the enthusiasm of a soldier and who loves

battle from an innate instinct for his business."

"Only those generals who gain successes, can set up dictators.

What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the

dictatorship."

|

The president told his new commander what he expected in a remarkably

perceptive and blunt letter. "I believe you to be a brave and skillful

soldier ...," wrote Lincoln. "You have confidence in yourself, which is

a valuable, if not an indispensable quality. You are ambitious, which,

within reasonable bounds, does good rather than harm." But Lincoln knew

Hooker had worked against Burnside—which "did a great wrong to the

country"—and had spoken of the need for a military dictator if the

North were to win the war. "Of course it was not for this, but in spite

of it, that I have given you the command," continued the president:

"Only those generals who gain successes, can set up dictators. What I

now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship."

In a communication dated January 31, 1863, Halleck spoke for Lincoln in

reiterating to Hooker what he had told Burnside earlier that month: "Our

first object was, not Richmond, but the defeat and scattering of Lee's

army." The president confirmed Halleck's language some two months later,

observing that "our prime object is the enemies' army in front of us,

and is not with, or about, Richmond."

The Army of the Potomac in January 1863 represented a poor weapon

with which Hooker might smite the Rebels. "Fighting Joe" inherited an

organization buffeted by defeat, lacking confidence in leaders who

engaged in bitter squabbling, plagued by breakdowns in the delivery of

pay and food, and suffering a high rate of desertion. An officer in the

140th New York described an "entire army struck with melancholy. . . .

The mind of the army, just now, is a sort of intellectual marsh in which

False Report grows fat, and sweeps up and down with a perfect audacity

and fierceness." Another soldier thought "the army is fast approaching a

mob." A man in the 155th Pennsylvania spoke darkly of the dismantling of

Hooker's force: "I like the idea for my part," he observed, "& I

think they may as well abandon this part of Virginia's bloody soil."

Many of the problems boiled down to the men's lack of faith in their

generals. "From want of confidence in its leaders and from no other

reason," summarized one observant New Yorker, "the army is fearfully

demoralized."

|

LINCOLN'S LETTER TO HOOKER

Executive Mansion

Washington, January 26, 1863

Major General Hooker:

General.

I have placed you at the head of the Army of the Potomac. Of course I

have done this upon what appears to me to be sufficient reasons and yet

I think it best for you to know that there are some things in regard to

which I am not quite satisfied with you. I believe you to be a brave and

skillful soldier, which, of course, I like. I also believe you do not

mix politics with your profession, in which you are right. You have

confidence in yourself, which is a valuable if not indispensable,

quality.

You are ambitious, which, within reasonable bounds, does good rather

than harm; but I think that during General Burnside's command of the

army you have taken counsel of your ambition, and thwarted him as much

as you could, in which you did a great wrong to the country and to a

most meritorious and honorable brother officer. I have heard, in such

way as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the Army and the

Government needed a Dictator. Of course it was not for this, but in

spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only those generals who

gain successes can set up dictators. What I now ask of you is military

success, and I will risk the dictatorship. The Government will support

you to the utmost of its ability, which is neither more nor less than it

has done and will do for all commanders. I much fear that the spirit

which you have aided to infuse into the army, of criticising their

commander and withholding confidence from him, will now turn upon you. I

shall assist you as far as I can to put it down. Neither you nor

Napoleon, if he were alive again, could get any good out of an army

while such a spirit prevails in it. And now beware of rashness. Beware

of rashness, but with energy and sleepless vigilance go forward, and

give us victories.

Yours very truly,

A. Lincoln

|

Hooker took a number of steps that quickly restored morale. He named

as medical director Jonathan Letterman, who oversaw improvements in food

and sanitation that helped to lower the incidence of illness among the

soldiers. Tackling the problem of desertion, Hooker tightened patrols

while also convincing Lincoln to issue a proclamation of amnesty. A new

system of furloughs for individuals and units with strong records went

into effect, a measure, noted one man, that triggered "joyous

anticipation" in the ranks. Known as a general who appreciated good

drink, Hooker mandated a whiskey ration for soldiers returning from

picket duty. Perhaps most important symbolically, the new commander

instituted a system of corps badges. Initially aimed at identifying the

units of shirkers, the badges soon became highly valued symbols that

engendered pride in belonging to a particular corps. Hooker probably did

not exaggerate when he commented after the war that this innovation "had

a magical effect on the discipline and conduct of our troops. . . . The

badge became very precious in the estimation of the soldier."

|

MORALE IN THE ARMY OF THE POTOMAC WAS AT LOW EBB AT THE TIME HOOKER

ASSUMED COMMAND. HE WOULD HAVE JUST THREE MONTHS TO TURN THINGS AROUND.

(BL)

|

|

HOOKER'S ADOPTION OF CORPS BADGES ENABLED OFFICERS TO IDENTIFY UNITS ON

THE BATTLEFIELD AND BUILT ESPRIT-DE-CORPS AMONG THE TROOPS. (BL)

|

The army also underwent reorganization. Hooker scrapped the Grand

Divisions of Burnside's tenure, which had grouped the Union corps into

larger administrative bodies. This required that he communicate with

eight corps—a cumbersome arrangement at best. Major General Oliver

Otis Howard, who led the Eleventh Corps, suggested that Hooker opted for

this arrangement because he "enjoyed maneuvering several independent

bodies." Far more pernicious was Hooker's decision to scatter the army's

artillery batteries among its infantry divisions, which removed the able

Brigadier General Henry J. Hunt from effective charge of the Federal

long arm. Hooker believed this move would promote strong bonds between

the infantry and artillery because soldiers "regarded their batteries

with a feeling of devotion." But its principal effect was to deny

Northern artillery the ability to mass for concentrated fire. Hooker

took the opposite approach with his mounted arm, which he gathered into

a Cavalry Corps under the direction of Major General George

Stoneman.

A canvass of Hooker's subordinate command reveals some competence and

a good deal of caution, but no brilliance. Closest to Hooker was Third

Corps commander Daniel F. Sickles, a former New York congressman who had

murdered his wife's lover in 1859, won acquittal, and then—to the

astonishment of Washington society—accepted Mrs. Sickles back into

his home. Innocent of military training and beholden to Hooker for his

advancement to major general, Sickles differed from the other corps

chiefs in his aggressiveness on the battlefield. The First Corps

belonged to Major General John F. Reynolds, a handsome Pennsylvanian

widely known then and since as the ablest corps commander in the

array—but whose record offers little evidence to substantiate that

lofty reputation. Major General Darius N. Couch, a Pennsylvanian who led

the Second Corps, emulated his idol George B. McClellan with a

conservative approach to war and politics. A third Pennsylvanian, Major

General George G. Meade, quietly presided over the Fifth Corps after a

solid but unspectacular record during the first two years of the

conflict. A pair of strong McClellan supporters, Major General John

Sedgwick and Major General Henry W. Slocum, commanded the Sixth and

Twelfth corps respectively. Neither had compiled a distinguished record;

indeed, Sedgwick's one memorable episode as a general consisted of

leading his division to ignominious disaster in the West Woods at

Antietam. Except for Sickles, all of these men had advanced partly

because of their ability to mask conservative political views in the

context of a war shifting to a more radical orientation concerning

emancipation and other issues.

|

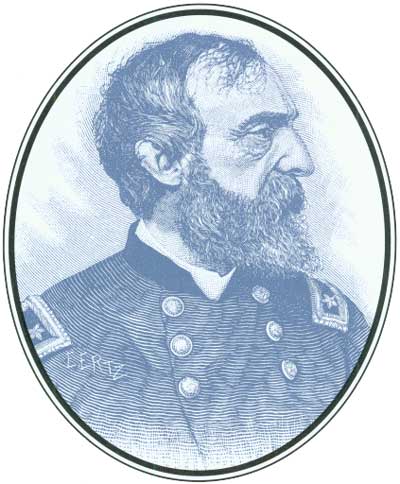

GEORGE STONEMAN COMMANDED THE UNION ARMY'S CAVALRY CORPS. "LET YOUR

WATCH WORD BE FIGHT," HOOKER TOLD HIM. (BL)

|

|

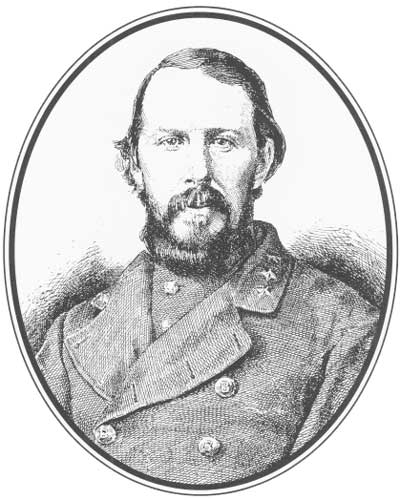

GEORGE G. MEADE (BL)

|

O. O. Howard of the Eleventh Corps stood out as a pious Republican

among predominantly Democratic peers. Hooker shared Howard's politics

but not his moral code. In a postwar interview, the former army

commander remarked savagely that Howard "was always a woman among

troops.... If he was not born in petticoats, he ought to have been, and

ought to wear them. He was always taken up with Sunday Schools and the

temperance cause." Howard inspired little devotion in his corps, which

counted among its ranks thousands of Germans who would have preferred

Major General Carl Schurz or some other German-speaking officer as their

commander. Taunted as "Dutchmen" throughout the army, the soldiers of

the Eleventh Corps stood apart from their comrades—just as their

commander stood apart from them. Adversity would bind them together in

the wake of Chancellorsville.

Despite the uncertain quality of many of its senior generals, the

Army of the Potomac approached the spring campaign as a formidable

force. Well supplied and equipped and vigorously led by Hooker, the army

numbered nearly 134,000 men of all arms and could carry 413 artillery

pieces into battle. Hooker described this host as "the finest army on

the planet." Others shared this view, including Edward Porter Alexander,

a perceptive Confederate artillerist who after the war wrote of

"Hooker's great army—the greatest this country had ever seen."

A series of reviews through the spring season allowed the army to

display its growing confidence and power. President Lincoln joined

Hooker in early April to preside over the most notable of these public

showings. Scores of thousands of men marched by the admiring general and

their commander in chief. After one of the reviews, a soldier in the

Second Massachusetts proudly proclaimed that the "Army of the Potomac is

a collection of as fine troops . . . as there are in the world." An

Ohioan seemed awestruck at such a magnificent display of the Republic's

martial resources: "Such a great army! Thunder and lightning! The

Johnnies could never whip this army!"

|

E. PORTER ALEXANDER (BL)

|

R. E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia prepared to meet their

imposing foe after enduring a very difficult winter and early spring.

Lee's own health remained uncertain. In early April he complained to his

wife of "a good deal of pain in my chest, back, & arms." "Some fever

remains," he added, and the doctors "have been tapping me all over like

an old steam boiler before condemning it." By April 11, he reported

himself much improved to his daughter Agnes: "I hope I shall recover my

strength," he wrote, through his pulse stood at about 90, "too quick for

an old man," according to his physicians.

The winter had forced hard choices on Lee. Unable to provision his

cavalry, he had dispersed it widely to secure sufficient fodder. James

Longstreet, head of the First Corps and Lee's senior lieutenant, also

had been detached from the army with the divisions of Major General

George E. Pickett and Major General John Bell Hood. Posted in Southside

Virginia near Suffolk, Longstreet's soldiers foraged on a grand scale

and stood ready to block Federal thrusts from Norfolk, or the coast of

North Carolina. Lee retained the divisions of Major General Richard H.

Anderson and Major General Lafayette McLaws from Longstreet's corps. and

Stonewall Jackson's entire Second Corps—the divisions of Major

General Ambrose Powell Hill, Brigadier General Robert F. Rodes, Major

General Jubal A. Early, and Brigadier General Raleigh E.

Colston—stood ready to rake the field against Hooker. Lee's

artillery counted 220 guns, and approximately 2,500 Confederate

cavalrymen were near at hand. The Army of Northern Virginia could muster

slightly fewer than 61,000 men in all—which meant it would face an

enemy more than twice its strength.

|

IN APRIL 1863, PRESIDENT LINCOLN TRAVELED TO STAFFORD COUNTY TO REVIEW

THE ARMY. HERE BRIGADIER GENERAL JOHN BUFORD'S CAVALRY DIVISION PASSES

IN REVIEW. (HW)

|

Superb leadership partially offset this daunting disparity in

numbers. Lee's record since June 1862 justified his reputation as an

unexcelled field commander. He had forged an unshakable bond with his

soldiers, and many Confederate civilians already viewed him as the

personification of their war effort. "Like [George] Washington, he is a

wise man, and a good man," noted a Georgia newspaper in late 1862, "and

possesses in an eminent degree those qualities which are indispensable

in the great leader and champion upon whom the country rests its hopes

of present success and future independence." Stonewall Jackson stood

second only to Lee in the estimation of the Confederate people (in

Europe he probably was more famous) and inspired similar confidence

among his men. As superior and loyal subordinate, Lee and Jackson formed

a partnership that accounted for much of the army's success. Major

General James E. B. "Jeb" Stuart complemented Lee and Jackson

beautifully. He brought unmatched skill in the arts of gathering

intelligence and screening the army to his work with the

cavalry—talents that would prove crucial in the upcoming campaign.

Finally, the Confederate artillery boasted a group of highly

intelligent, innovative, and cocky young officers who benefited from a

recent reorganization that placed Southern batteries in battalions.

Unlike their opponents, Confederate gunners would be able to bring

several batteries to bear on different sectors of the battlefield—a

tactic that diminished Union advantages in firepower and quality of

ordinance.

Splendid Confederate morale brightened the prospects for Southern

success. Lee's soldiers had overcome long odds in winning spectacular

victories, and they believed their generals would place them in a

position to do so again.

|

Splendid Confederate morale brightened the prospects for Southern

success. Lee's soldiers had overcome long odds in winning spectacular

victories, and they believed their generals would place them in a

position to do so again. Stephen Dodson Ramseur, a youthful brigadier in

Robert Rodes's division, spoke for many in the army when he confidently

stated that the "vandal hordes of the Northern Tyrant are struck down

with terror arising from their past experience. They have learned to

their sorrow that this army is made up of veterans equal to those of the

'Old Guard' of Napoleon." When Hooker seemed loath to advance during one

spell of dry weather in March, Ramseur confidently attributed it to

Fighting Joe's desire "to postpone the day of his defeat and

humiliation." Lee reciprocated this confidence, seeing in his soldiers

the capacity to offset much of the North's substantial edge in men and

materiel.

Hooker's preponderant strength carried with it the strategic

initiative. Well aware of Burnside's costly failure to bludgeon his way

through Lee's defenders at the battle of Fredericksburg, he entertained

no thought of challenging entrenched Confederates head-on. His initial

plan called for turning Lee's left flank with the Cavalry Corps.

Stoneman would take his command across the Rappahannock well upstream

from Fredericksburg, after which the troopers would strike south and

southeast to disrupt communications and transportation in Lee's rear.

Expecting Lee to withdraw toward the Confederate capital in the face of

this threat, Hooker would push his infantry over the Rappahannock and

pursue the fleeing Rebels. "I have concluded that I will have more

chance of inflicting a heavier blow upon the enemy by turning his

position to my right," the general informed President Lincoln on April

11, "and, if practicable, to sever his connections with Richmond with my

dragoon force and such light batteries as it may be deemed advisable to

send with them." The next day Hooker urged Stoneman to remember that

"celerity, audacity, and resolution are everything in war," pointedly

telling the cavalryman that "on you and your noble command must depend

in a great measure the extent and brilliancy of our success."

|

JAMES E.B. STUART (LC)

|

The cavalry's turning march, begun promisingly enough on April 13,

quickly slowed to a halt when heavy rains turned the Rappahannock into a

frothing, impassable torrent. Only a single brigade made it across the

river before the water rose precipitately and prompted Stoneman to abort

the effort. "I greatly fear it is another failure already," an anguished

Lincoln commented when Hooker explained Stoneman's problems. The

president, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, and General Halleck joined

Hooker at Aquia on April 19 to discuss strategy.

Hooker greeted his visitors with plans for a more ambitious turning

operation. Stoneman's role remained essentially the same, but now

Federal infantry would march simultaneously with their mounted comrades.

While the Cavalry Corps crossed the river and began its dash into the

Virginia interior, the 42,000 men of the Eleventh, Twelfth, and Fifth

corps would move upriver, past well-defended Banks and United States

fords, to negotiate the Rappahannock at Kelly's Ford. Once on the Rebel

side of the river, they would hasten south to cross the Rapidan River at

Germanna and Ely's fords, proceed into a heavily wooded area known as

the Wilderness of Spotsylvania, concentrate at a crossroads called

Chancellorsville, and then strike Lee's army from the west. Meanwhile,

two divisions from Couch's Second Corps—another 10,000

men—would proceed to United States Ford and wait for Meade's Fifth

Corps, marching east toward Lee, to drive Confederate defenders away

from the river.

|

WHEN UNION SOLDIERS CROSSED THE RAPIDAN RIVER, THEY ENTERED A

70-SQUARE-MILE AREA OF DENSE THICKETS KNOWN AS THE WILDERNESS. MANY

WOULD NEVER LEAVE ITS GLOOMY REALM. (NPS)

|

Hooker hoped to hold Lee's attention at Fredericksburg by shifting

the Sixth and First corps, 40,000 strong and under John Sedgwick's

overall command, to the Rebel side of the Rappahannock below town.

Sedgwick's troops would threaten an attack against Stonewall Jackson's

divisions holding the Confederate right flank. Further to mask Hooker's

turning movement, Daniel Sickles's Third Corps and one division of the

Second Corps, which together mustered nearly 25,000 muskets. would

remain in their camps at Falmouth in plain view of watching

Confederates.

|

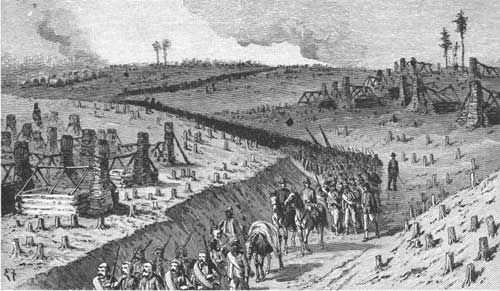

THE RIGHT WING OF THE UNION ARMY BROKE CAMP ON APRIL 27 AND CONFIDENTLY

HEADED UP THE RAPPAHANNOCK RIVER. WITHIN TWO WEEKS IT WOULD BE BACK

WHERE IT STARTED. (BL)

|

|

EACH UNION SOLDIER LEFT CAMP WITH UPWARD OF 60 POUNDS OF EQUIPMENT. AS

THE DAY DREW HOTTER, INDIVIDUALS CAST OFF OVERCOATS, BLANKETS, AND OTHER

CUMBERSOME ITEMS. (LC)

|

If Hooker's grand design were to work, the three corps in the turning

column should break clear of the Wilderness as quickly as possible.

Covering approximately seventy square miles, the Wilderness extended

south from the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers with irregular borders

running some three miles south and two miles east of Chancellorsville.

Few roads traversed this gloomy forest, and only a handful of farms

broke its dismal hold on the countryside. No longer dominated by mature

growth, it was an ugly, scrub wasteland repeatedly cut over to feed

hungry little iron furnaces in the region. Dense underbrush, choking

vines, thickets of blackjack and hickory, and spindly saplings posed

wicked obstacles to the passage of troops and would nullify to a large

degree the superior Federal artillery. Just a few miles east of

Chancellorsville the Wilderness gave way to open country where Northern

numbers and equipment could have full weight. That was where the turning

column should seek its outnumbered and outgunned enemy.

Efficient execution of the Union plan would squeeze Lee between

powerful forces in front and rear while Stoneman's cavalry wreaked havoc

on Confederate lines of communication and supply. Hooker believed his

opponent must either retreat, to be hounded by a pursuing Army of the

Potomac, or attack the Federals on unfavorable ground. Either scenario

promised victory sweeping enough to lay to rest the troubling ghosts of

Fredericksburg and other Union failures against Lee. An admiring Porter

Alexander awarded Hooker's design high marks: "On the whole I think this

plan was decidedly the best strategy conceived in any of the campaigns

ever set on foot against us," he wrote in his memoirs. "And the

execution of it was, also, excellently managed, up to the morning of May

1st."

|

|