|

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

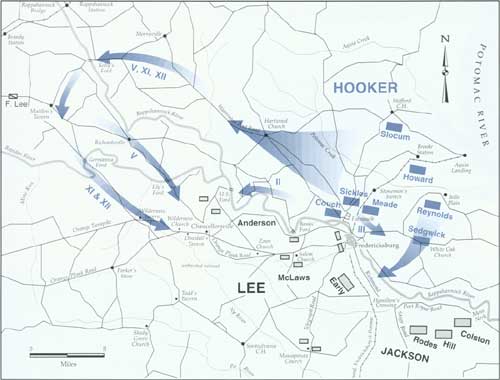

THE CAMPAIGN BEGINS: APRIL 27-30

Reynolds and Sedgwick cross the Rappahannock River below

Fredericksburg to hold the Confederate army in place while Hooker leads

the Fifth, Eleventh, and Twelfth Corps across Kelly's Ford, above town,

effectively flanking Lee's Fredericksburg defenses. Sickles supports the

Union army's right wing, while Conch sends two divisions of the Second

Corps to U.S. Ford as a diversion.

|

Initial execution of the plan was splendid. Three Federal corps

marched upriver on April 27, got across the Rappahannock and Rapidan

with minimal delays, and by late afternoon of April 30 clustered near

Chancellorsville. Couch's two divisions hurried to join them—having

crossed the Rappahannock at United States Ford when Confederates on the

right bank of the river withdrew in response to reports of heavy enemy

activity to the west. Back at Fredericksburg, Union pontoons were in

place by dawn on April 29, allowing thousands of Sedgwick's infantry to

move into position opposite Lee's lines below the town. Musketry and

artillery fire soon echoed along the river, continuing through the

balance of that day and the next.

|

WHILE HOOKER'S MAIN FORCE CROSSED THE RAPPAHANNOCK UPRIVER FROM

FREDERICKSBURG, SOLDIERS OF THE FIRST AND SIXTH CORPS CROSSED ON PONTOON

BRIDGES BELOW THE TOWN. (HW)

|

Many Union soldiers sensed that they had stolen a march on the crafty

Lee. On the afternoon of April 30, George Meade shed his usual restraint

to greet Henry Slocum at Chancellorsville with unabashed enthusiasm:

"This is splendid, Slocum; hurrah for old Joe; we are on Lee's flank,

and he does not know it. You take the Plank Road toward Fredericksburg,

and I'll take the Pike, or vice versa, as you prefer, and we'll get out

of this Wilderness."

Meade alluded to the major east-west routes through the

Wilderness—the Orange Plank Road and the Orange Turnpike, both of

which connected Orange Court House and Fredericksburg. The turnpike and

plank road entered the area on separate beds but came together at

Wilderness Church west of Chancellorsville to form a single road. They

diverged again at Chancellorsville with the plank road veering sharply

southeast, only to rejoin the turnpike just east of Zoan Church for the

last few miles to Fredericksburg. Unnamed by Meade the River Road

provided a third route to the rear of Lee's position along the

Rappahannock, angling northeast from Chancellorsville to trace a large

arc on its way to the town. These three avenues lay open to the Federal

flanking forces on the afternoon of April 30, but there would be no more

marching that day. At 2:15 P.M., Hooker dispatched instructions from

Federal headquarters at Falmouth for the elements of the turning column

to halt at Chancellorsville, where he would join them that night.

Hooker arrived at Chancellorsville between 5:00 and 6:00 P.M. He

found not a town or village but a rather imposing country residence.

Begun in the early nineteenth century by the Chancellor family, the

building had been enlarged several times, functioning as an inn on the

turnpike for many years. Traffic had decreased markedly by 1860, and the

Chancellors then used the structure, which they called Chancellorsville,

as a family home. The rambling brick house would serve as headquarters

for the Army of the Potomac. Before departing for Chancellorsville (but

after issuing his orders halting the turning column), Hooker had

transmitted a congratulatory message: "It is with heartfelt

satisfaction," he stated, "the commanding general announces to the army

that the operations of the last three days have determined that our

enemy must either ingloriously fly, or come out from behind his defenses

and give us battle on our own ground, where certain destruction awaits

him."

|

"O THE HORROR OF THAT DAY!"

Although its name implies that it was a village Chancellorsville was

actually nothing more than a large brick house with a few scattered

dependencies set in the heart of the Wilderness. The building was

constructed by the Chancellor family in the early 1800s as an inn to

accommodate travelers using the Orange Turnpike, and Frances Chancellor

and her family were living at the house in 1863, when Joe Hooker

occupied it as his headquarters. For two days Mrs. Chancellor, her

children, and a few other local people remained sheltered in the house

while the battle raged around them. But on May 3 Confederate artillery

shells set the building on fire, compelling those inside to flee for

safety. Sue Chancellor, then an eleven-year-old girl, described the

arrival of the Union army at her home and the battle that followed. The

Union officer she mentions was Lieutenant Colonel (later General) Joseph

Dickinson of Hooker's staff.

"There were in the house my mother, her six daughters, her half-grown

son, Miss Kate F, Aunt Nancy, and a little negro girl left by her mother

when she went away to the Yankees. We put on all the clothes we could,

and my sisters fastened securely in their hoop skirts the spoons and

forks and pieces of the silver tea service which the engineers had given

my mother.. . . Other valuables were secreted as best they could be.

Presently the Yankees began to come, and they said that Chancellorsville

was to be General Hooker's headquarters, and we must all go into one

room at the back of the house. They took all our comfortable rooms for

themselves, while we slept on pallets on the floor . . . . General

Hooker did not come until the next day. He paid no attention to my

mother, but walked in and gave his orders. We never sat down to a meal

again in that house, but they brought food to us in our room. If we

attempted to go out, we were ordered back. We heard cannonading, but did

not know where it was. We were joined by our neighbors, who fled or were

brought to Chancellorsville house for refuge, until there were sixteen

women and children in that room. From the windows we could see couriers

coming and going and knew that the troops were cutting down trees and

throwing up breastworks. I know now that they were pretty well satisfied

with their position and were confident of victory.

|

ON APRIL 30. THE CHANCELLORSVILLE CLEARING WAS FILLED WITH MULES,

SOLDIERS, AND WAGONS. FOR THE NEXT THREE DAYS IT WOULD BE THE HEART OF

THE UNION ARMY'S POSITION. (LC)

|

Well, we got through Thursday and Friday as best we could, but on

Saturday, the 2d of May, the firing was much nearer, and General Hooker

ordered us to be taken to the basement. The house was full of wounded.

They had taken our sitting room as an operating room and our piano as an

amputating table. One of the surgeons came to my mother and said, 'There

are two wounded Rebels here, and if you wish you can attend to them,'

which she did.

There was water in the basement over our shoetops, and one of the

surgeons brought my mother down a bottle of whisky and told her that we

should all take some, which we did, with the exception of Aunt Nancy,

who said: 'No sah, I ain't gwine tek it; I might git pizened.'

There was firing and fighting, and they were bringing in the wounded

all that day; but I must say that they did not forget to bring us some

food. It was late that day when the awful time began. Cannonading on all

sides and such shrieks and groans, such commotion of all kinds! We

thought that we were frightened before, but this was beyond everything

and kept up until after dark. Upstairs they were bringing in the

wounded, and we could hear their screams of pain. This was Jackson's

flank movement, but we did not know it then. Again we spent the night,

sixteen of us, in that one room, the last night in the old house.

Early in the morning they came for us to go into the cellar, and in

passing through the upper porch I saw how the chairs were riddled with

bullets and the shattered columns which had fallen and injured General

Hooker. O the horror of that day! The piles of legs and arms outside the

sitting room window and the rows and rows of dead bodies covered with

canvas! The fighting was awful, and the frightened men crowded into the

basement for protection from the deadly fire of the Confederates, but an

officer came and ordered them out, commanding them not to intrude upon

the terrorstricken women. Presently down the steps the same officer came

precipitously and bade us get out at once, 'For madam, the house is on

fire, but I will see that you are protected and taken to a place of

safety.' This was Gen. Joseph Dickinson. . . . Cannon were booming and

missiles of death were flying in every direction as this terrified band

of women and children came stumbling out of the cellar. If anybody

thinks that a battle is an orderly attack of rows of men, I can tell

them differently, for I have been there.

"The woods around the house were a sheet of fire, the air was

filled with shot and shell, horses were running, rearing, and screaming,

the men, a mass of confusion, moaning, cursing, and praying."

|

The sight that met our eyes as we came out of the dim light of that

basement beggars description. The woods around the house were a sheet of

fire, tThe air was filled with shot and shell, horses were running,

rearing, and screaming, the men, a mass of confusion, moaning, cursing,

and praying. They were bringing the wounded out of the house, as it was

on fire in several places .... Slowly we picked our way over the

bleeding bodies of the dead and wounded, General Dickinson riding ahead,

my mother walking alongside with her hand on his knee, I clinging close

to her, and the others following behind. At the last look our old home

was completely enveloped in flames.

|

Once at the crossroads, Hooker brimmed with confidence. Sickles's

Third Corps would join the turning column early the next morning. The

commanding general would then oversee an advance he believed certain to

unnerve the previously unflappable R. F. Lee. Within earshot of a

newspaper correspondent, Hooker stated, "The rebel army is now the

legitimate property of the Army of the Potomac. They may as well pack up

their haversacks and make for Richmond. I shall be after them."

|

RESPONSIBILITY FOR GUARDING THE FORDS ABOVE FREDERICKSBURG FELL TO DICK

ANDERSON. WHEN UNION TROOPS CROSSED BEYOND HIS LEFT FLANK, ANDERSON FELL

BACK TO ZOAN CHURCH. (BL)

|

Lee's position did seem nearly hopeless. Caught between the hammer of

the flanking force at Chancellorsville and Sedgwick's solid anvil at

Fredericksburg, his best option might be to slip southward in search of

a better tactical situation. But as so often in the past, the

Confederate chieftain opted for a daringly unpredictable response. Jeb

Stuart's hardworking troopers—free to roam the flanks of the army

because so many of Stoneman's cavalrymen had ridden

southward—supplied intelligence on April 29 about Federal crossings

at Kelly's Ford and enemy columns moving toward the fords on the

Rapidan. That evening Lee ordered Richard H. Anderson to go to

Chancellorsville and instructed Lafayette McLaws to prepare his division

to follow. Anderson reached his destination about midnight to find

Brigadier General William Mahone's and Brigadier General Carnot Posey's

brigades, which had fallen back from United States Ford earlier in the

day. Apprised that a heavy force of Union infantry was bearing down on

the crossroads—and under orders from Lee "to select a good line and

fortify it strongly"—Anderson withdrew to a ridge just beyond the

eastern edge of the Wilderness. This position, near a small Baptist

church with the unusual name Zoan, covered the plank road, the turnpike,

and the Old Mine or Mountain Road that linked the turnpike with United

States Ford. Soon reinforced by a third of his brigades, Brigadier

General Ambrose R. Wright's Georgians, Anderson ordered the men to dig

in. Their efforts created some of the first field fortifications

constructed by the Army of Northern Virginia.

|

OPTIMISM PERVADED THE UNION RANKS ON THE NIGHT OF APRIL 30 "OUR ENEMY

MUST NOW INGLOURIOUSLY FLY." HOOKER ANNOUNCED TO THE ARMY, "OR COME OUT

FROM BEHIND HIS DEFENSES AND GIVE US BATTLE ON OUR OWN GROUND. WHERE

CERTAIN DESTRUCTION AWAITS HIM." (NPS)

|

Through a tense April 29 and into the next day, Lee watched Union

movements at Fredericksburg and pondered intelligence about activity

upriver. Hooker had kept him off balance since February, when he had

confessed to Mrs. Lee his inability to fathom the Federal commander's

intentions: "I owe Mr. F. J. Hooker no thanks for keeping me here in

this state of expectancy. He ought to have made up his mind long ago

what to do." Uncertainty ended on April 30 when Lee decided that

Sedgwick intended nothing more than a facade of aggressiveness at

Fredericksburg. "It was now apparent that the main attack would be made

upon our flank and rear," Lee later explained. "It was therefore

determined to leave sufficient troops to hold our lines [at

Fredericksburg], and with the main body of the army to give battle to

the approaching column."

How would Lee divide his small arrmy to keep an eye on Sedgwick,

Jubal Early would remain at Fredericksburg with his division from

Jackson's Second Corps. Brigadier General William Barksdale's brigade of

Mississippians from McLaws's division, and roughly one-quarter of the

army's artillery—a total of 9,000 soldiers and 56 guns. The rest of

the Second Corps would march westward to join Anderson and McLaws for a

showdown with Hooker's main body.

|

WHILE HOOKER CROSSED THE RAPPAHANNOCK RIVER ABOVE FREDERICKSBURG,

SEDGWICK'S GUNS SHELLED LEE'S LINE BEHIND THE CITY IN AN EFFORT TO HOLD

THE CONFEDERATE ARMY IN PLACE. (LC)

|

|

|