|

Although thoroughly beaten mentally, Hooker maintained his outward

bravado. He told Couch that Lee was "just where I want him; he must

fight me on my own ground." But neither Couch nor others at Federal

headquarters doubted the magnitude of the day's lost opportunity. "The

retrograde movement had prepared me for something of the kind," Couch

later wrote of Hooker's hollow claims, "but to hear from his own lips

that the advantages gained by the successful marches of his lieutenants

were to culminate in fighting a defensive battle in that nest of

thickets was too much." Couch left Hooker's presence "with the belief

that my commanding general was a whipped man." Late that afternoon

Federal corps chiefs at Chancellorsville received a prophetic message

from Hooker: "The major general commanding trusts that a suspension in

the attack to-day will embolden the enemy to attack him."

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

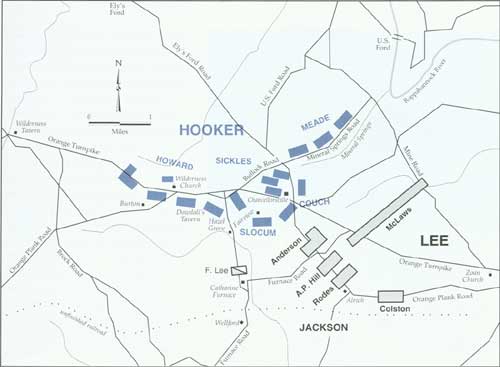

SITUATION: MAY 1, NIGHT

Hooker falls back to a tight defensive line around Chancellorsville.

Meade holds a position on the river, Couch and Slocum occupy the center

of the line, and Howard's corps stretches west out the Orange Turnpike.

Sickles is in reserve at Chancellorsville. Lee, meanwhile, moves and

occupies the ridge abandoned by Hooker earlier in the day.

|

The initiative had passed to Lee—of all Confederate generals the

one most likely to attack a vacillating enemy. The Army of Northern

Virginia remained in a perilous situation, lodged between Hooker and

Sedgwick. Lee and Jackson met that night where a narrow lane from

Catharine Furnace intersected the plank road about a mile southeast of

Hooker's headquarters. They sat on cracker boxes abandoned by the

retreating Yankees, light from a modest fire flickering in the damp air.

How could they get at the enemy? Lee had ridden toward the Union left

during the afternoon and found no opening. Rough ground, numerous

Federals, and an absence of roads rendered that Union flank safe.

Confederate engineering officers reconnoitered the enemy's center and

reported it also too strong to assail. Reports from various

sources—including Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee of Stuart's

cavalry, various staff officers, and local residents—suggested that

Hooker's right might be vulnerable. If enough infantry could move

undetected across Hooker's front and hit the exposed flank, Lee might

forge a decisive victory. Key information about possible routes for the

flank march came from Charles Beverly Wellford, a veteran of Lee's army

now overseeing Catharine Furnace (a Wellford enterprise named for the

family's matriarch), Jackson's gifted cartographer Jedediah Hotchkiss,

and Beverly Tucker Lacy, a clergyman with Jackson whose brother lived in

the area.

|

ON THE NIGHT OF MAY 1, LEE AND JACKSON MET TOGETHER TO PLAN THEIR

STRATEGY FOR THE COMING DAY. WHEN THEIR CAVALRY REPORTED THAT HOOKER'S

RIGHT FLANK WAS "IN THE AIR." LEE ORDERED JACKSON TO ATTACK IT.

(BL)

|

Lee decided in the early hours of May 2 on a breathtakingly dangerous

gamble. He would divide his outnumbered army for a second time, sending

28,000 men of Jackson's Second Corps around Hooker's front to launch an

attack on the Union right flank. With the brigades under Anderson and

McLaws—roughly 13,000 men supported by 24 guns—Lee would

strive to occupy Hooker's attention until Jackson got into position.

Should Hooker discover Lee's intention, the Federals could crush the

pieces of the Army of Northern Virginia in detail (Jubal Early's small

force remained outnumbered about four to one at Fredericksburg).

Doubtless aware of that grim possibility, Lee and Jackson discussed the

path the Second Corps would take. Lee would leave all details of the

movement to Jackson. Illustrating by graphic example of what he hoped to

achieve, Lee chose a moment to align a batch of broomstraws on a

box—then brushed them to the ground. The generals parted just

before dawn on May 2. Lee would see to the demonstration in front of

Hooker while Jackson started his divisions on a march that would

culminate in the Civil War's most famous flank attack.

|

IN THE AFTERNOON, DAVID BIRNEY'S DIVISION PUSHED SOUTH TO THE CATHARINE

FURNACE IN AN EFFORT TO DISRUPT JACKSON'S MARCH. HE WAS TOO LATE. (NPS)

|

Jackson's column was in motion between seven and eight o'clock. Its

twelve-mile route would follow the Catharine Furnace Road to the

ironworks, continuing southwest to the junction with the Brock Road.

Turning left at that point, the men would march a few hundred yards

south before turning right onto a narrow woods road that eventually

deposited them back onto the Brock Road, which in turn would take them

to the plank road. The plan called for the attack to proceed east along

the plank road. Jackson rode near the front of Rodes's division, which

led the march. Colston's and then Hill's commands stretched out behind.

Brigadier General Alfred H. Colquitt's brigade of Georgians had the

honor of leading the march. At about eight o'clock, the first of

Jackson's infantry passed Lee's bivouac on their way toward the furnace.

"Old Jack" reined in his sorrel to have a few quiet words with Lee. He

gestured toward Catharine Furnace, Lee nodded, and Jackson took his

leave. Lee never saw his redoubtable lieutenant again.

Hours of hard work and anxiety lay ahead for Lee. He helped place the

soldiers of Anderson and McLaws, watched carefully for Hooker's

reaction, and wondered about Jackson's progress and Jubal Early's

situation at Fredericksburg. The Confederate line fronting Hooker

eventually extended three and one-half miles from near Catharine Furnace

on the southwest, where Carnot Posey's brigade was posted, northwest

across the plank road and the turnpike to the Old Mine Road. Only seven

brigades strong, this force feigned numerous attacks. Individual

regiments frequently deployed huge numbers of skirmishers to create the

illusion of greater numbers. Federals easily repulsed the Confederate

feints but never followed up with counterattacks. Lee knew his thin line

could resist no serious northern advance. "It is plain that if the enemy

is too strong for me here," he informed Jefferson Davis, "I shall have

to fall back, and Fredericksburg must be abandoned." Lee also told the

president about the flank march: "I am now swinging around to my left to

come up in his [Hooker's] rear."

|

JACKSON'S INFANTRY SENSED THAT THEY WERE HEADED AROUND THE UNION ARMY,

AND IT PUT THEM IN HIGH SPIRITS. "TELL OLD JACK WE'RE ALL A-COMING,"

THEY JOKED TO PASSING STAFF OFFICERS. "DON'T LET HIM BEGIN THE FUSS TILL

WE GIT THAR!" (BL)

|

Jackson's men trod on narrow paths damp and soft enough for easy

marching. Cavalry preceded the infantry and screened the right flank.

Each division marched with its artillery, ambulances, and ammunition

trains behind it. From head to tail the column stretched ten miles. Four

hours elapsed between the time the first and last brigades passed Lee's

bivouac. Jackson hoped to maintain his usual pace of one mile every

twenty-five minutes with a ten-minute break each hour. Pleasantly cool

under clear skies when the movement began, the temperature climbed

steadily as the day wore on. Colonel Charles T. Zachry of the

Twenty-Seventh Georgia, a regiment in Colquitt's brigade, remarked six

days later that "the march was a trying one for the men; the day was

very warm; many fell out of ranks exhausted, some fainting and having

spasms."

Noted for prodigious marching in the Shenandoah Valley and elsewhere,

Jackson's famous "foot cavalry" would consume the entire day reaching

its jump-off point and forming for the assault. Why did it take so long?

One observer explained: "Every little inequality of ground, & every

mud hole, especially if the road be narrow, causes a column to string

out & lose distance. So that, though the head may advance steadily,

the rear has to alternately halt & start, & halt & start, in

the most heartbreaking way, wearing out the men and consuming precious

daylight, often beyond the calculations even of experienced

soldiers."

So many Confederates on so long a march invited detection. Scarcely a

mile beyond Lee's bivouac, the column became visible to Federals a mile

and a quarter northwest on the high plateau called Hazel Grove.

Brigadier General David Bell Birney's division of Sickles's corps held

Hazel Grove, and at about 8:00 A.M. Birney informed Sickles "that a

continuous column of infantry, trains, and ambulances was passing my

front toward the right." Birney ordered the rifled pieces of Battery B,

First New Jersey Artillery, to open fire on the Confederates, causing

them to double-quick past the gap in the woods. Sickles subsequently

rode to Hazel Grove to watch the passing Confederates. "The continuous

column . . . was observed for three hours moving apparently in a

southerly direction toward Orange Court-House," wrote Sickles in his

report of the battle. "I hastened to report these movements through

staff officers to the general-in-chief, and communicated the substance

of them in the same manner to Major-General Howard, on my right, and

also to Major-General Slocum, inviting their cooperation in case the

general-in-chief should authorize me to follow up the enemy and attack

his columns."

|

ENGRAVINGS LIKE THIS ONE TENDED TO PORTRAY BATTLES AS TIDY, WELL MANAGED

AFFAIRS. SUE CHANCELLOR KNEW OTHERWISE. "IF ANYBODY THINKS THAT A BATTLE

IS AN ORDERLY ATTACK OF ROWS OF MEN, I CAN TELL HIM DIFFERENTLY," SHE

LATER ASSERTED. (LC)

|

Shortly after nine o'clock, a courier from Birney found Hooker at the

Chancellor house and explained about the Confederate column. Hooker had

been up since before sunrise and already had examined his right flank.

Troops had cheered as he rode by, and he remarked that the Union

position seemed strong—which it was if Confederates attacked from

the south. Alerted by Birney's message, Hooker scanned the area near

Catharine Furnace through his fieldglasses. He caught glimpses of the

Confederates in two places —the break in the woods where Birney had

seen them and a section of the Furnace Road that ran south from the iron

works toward the Wellford house. Lee's men might be retreating, thought

Hooker, but they also might be searching for an opening to strike the

Union right flank. His morning inspection had revealed that Howard's

line offered little strength facing west. In a dispatch dated 9:30 A.M.,

Hooker warned Howard to prepare for trouble from that direction: "We

have good reason to suppose the enemy is moving to our right. Please

advance your pickets for purposes of observation as far as may be safe

in order to obtain timely information of their approach."

|

RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE UNION DISASTER ON MAY 2 FELL SQUARELY ON THE

SHOULDERS OF O. O. HOWARD, WHO FAILED TO HEED NOT ONLY HOOKER'S WARNING

BUT THE WARNINGS OF HIS OWN MEN. (LC)

|

Although Howard later claimed this dispatch never reached him, he

knew from other sources that Confederates might be marching toward his

right. He informed Hooker at 10:50 A.M. about "a column of infantry

moving westward on a road parallel with this [the turnpike] on a ridge

about 1-1/2 to 2 m[iles] south of this." Howard assured his commander

that he was "taking measures to resist an attack from the west." In

fact, he did virtually nothing to rearrange his corps, the vast majority

of which continued to face south along the turnpike.

While Howard contented himself with nominal adjustments to his line,

Hooker remained cautious and Dan Sickles exuded a restless determination

to strike the Rebels. Passing up the chance to launch a major assault

against the enemy's column, Hooker did send discretionary orders for

Sedgwick "to attack the enemy in his front" if "an opportunity presents

itself with a reasonable expectation of success." Sickles received

permission at noon "to advance cautiously toward the road followed by

the enemy, and harass the movement as much as possible."

|

WILDERNESS CHURCH STOOD AT THE CENTER OF HOWARD'S LINE. CARL SCHURZ

WOULD LATER FORM HIS DIVISION NEAR THE CHURCH. FACING WEST, IN AN EFFORT

TO MEET JACKSON'S ATTACK. (NPS)

|

These instructions came too late to interfere with Jackson's main

body. The trains, ambulances, and other vehicles accompanying the column

had left the Furnace Road to follow alternate paths that carried them

safely beyond Federal pressure at the ironworks. Jackson also had

detached the Twenty-third Georgia of Colquitt's brigade to guard the

rear of the column. The Georgians engaged elements of Birney's division

and Colonel Hiram Berdan's sharpshooters near Catharine Furnace during

the early afternoon. Driven south from the furnace, the Twenty-third

made a stand just north of the Wellford house in a portion of the same

unfinished railroad cut Wright's brigade had used the day before. The

Federals finally overran this position about 5:00 P.M., capturing most

of the defenders (Colonel Emory Fiske Best of the Twenty-third fled the

cut and subsequently was court-martialed and convicted of cowardice).

Two brigades from A. P. Hill's division, which had turned back to

support Best's regiment and now deployed on an open plateau near the

Wellford place, efficiently contained Sickles's success.

Most of Jackson's infantry marched on unaware that Sickles's troops

nipped at the rear of their column. They reached the Brock Road—the

principal north-south artery through that part of the

Wilderness—and turned left as planned, crossed a pair of small

ridges, then made a right turn onto a narrow woods path that took them,

four abreast, northward to a reunion with the Brock Road. A short

distance more and they reached the junction of the Brock and Orange

Plank roads. Here Jackson had envisioned turning east on the plank road

to cover the final two miles before striking the enemy at Wilderness

Church. Instead he found Fitzhugh Lee with exciting news. Taking Jackson

east along the plank road, Lee ascended to high ground on the Burton

farm whence he gestured toward a memorable sight: To their front, spread

out along the turnpike, were thousands of Federal soldiers at rest. Arms

stood stacked, and wisps of smoke from campfires climbed lazily skyward.

No sign indicated any expectation of a Confederate assault from the

west. Fitz Lee later recalled that Jackson's eyes "burned with a

brilliant glow, lighting his sad face."

|

JACKSON VIEWS THE UNION LINES

On May 2,1863, Stonewall Jackson led his corps through the Wilderness

toward the Union army's right flank, held by Major General Oliver O.

Howard's Eleventh Corps. Jackson believed Howard's line ended near the

Wilderness Church and therefore planned to make his attack up the Orange

Plank Road. As he neared the plank road that afternoon, however, he met

Major General Fitzhugh Lee, whose cavalry was screening his march. Lee

asked Jackson to follow him down the plank road to the Burton farm,

which stood on a knoll just half a mile from the Union line. There,

Jackson saw that Howard's line actually extended a mile beyond the

church, making an attack up the plank road impractical. Based on this

information, he had his corps continue up the Brock Road to the Orange

Turnpike, thereby placing it squarely on Howard's exposed flank. In a

speech made sixteen years after the battle, Fitz Lee described his

meeting with Jackson at the Burton farm:

|

FITZHUGH LEE (BL)

|

"Jackson was marching on. My cavalry was well in his front. Upon

reaching the Plank road, some five miles west of Chancellorsville, my

command was halted, and while waiting for Jackson to come up, I made a

personal reconnaissance to locate the Federal right for Jackson's

attack. With one staff officer, I rode across and beyond the Plank road,

in the direction of the Old turnpike, pursuing a path through the woods,

momentarily expecting to find evidence of the enemy's presence. Seeing a

wooded hill in the distance, I determined, if possible, to get upon its

top, as it promised a view of the adjacent country. Cautiously I

ascended its side, reaching the open spot upon its summit without

molestation. What a sight presented itself before me! Below, and but a

few hundred yards distant, ran the Federal line of battle. I was in rear

of Howard's right. There were the line of defence, with abatis in front,

and long lines of stacked arms in rear. Two cannon were visible in the

part of the line seen. The soldiers were in groups in the rear,

laughing, chatting, smoking, probably engaged, here and there, in games

of cards, and other amusements indulged in while feeling safe and

comfortable, awaiting orders. In rear of them were other parties driving

up and butchering beeves ... So impressed was I with my discovery, that

I rode rapidly back to the point on the Plank road where I had left my

cavalry, and back down the road Jackson was moving until I met

'Stonewall' himself. 'General,' said I, 'if you will ride with me,

halting your column here, out of sight, I will show you the enemy's

right, and you will perceive the great advantage of attacking down the

Old turnpike instead of the Plank road, the enemy's lines being taken in

reverse. Bring only one courier, as you will be in view from the top of

the hill.' Jackson assented, and I rapidly conducted him to the point of

observation. There had been no change in the picture.

"His eyes burned with a brilliant glow, lighting up a sad face.

His expression was one of intense interest, his face was colored

slightly with the paint of approaching battle, and radiant at the

success of his flank movement."

|

I only knew Jackson slightly. I watched him closely as he gazed upon

Howard's troops. It was then about 2 P.M. His eyes burned with a

brilliant glow, lighting up a sad face. His expression was one of

intense interest, his face was colored slightly with the paint of

approaching battle, and radiant at the success of his flank movement....

To the remarks made to him while the unconscious line of blue was

pointed out, he did not reply once during the five minutes he was on the

hill, and yet his lips were moving. From what I have read and heard of

Jackson since that day, I know now what he was doing then. Oh! 'beware

of rashness,' General Hooker. Stonewall Jackson is praying in full view

and in rear of your right flank!...

'Tell General Rodes,' said he, suddenly whirling his horse towards

the courier, 'to move across the Old plank-road; halt when he gets to

the Old turnpike, and I will join him there.' One more look upon the

Federal lines, and then be rode rapidly down the hill."

|

It was nearly 3:00 P.M. Much of the day already had been taken up by

marching, hut Jackson might achieve complete surprise if his column

continued on to the turnpike before turning east. "Tell General Rodes to

move across the Plank Road" he snapped to a courier, "halt when he gets

to the old turnpike, and I will join him there." Before riding to join

his men, Jackson scribbled a note to R. E. Lee: "I hope as soon as

practicable to attack... The leading division is up and the next two

appear to be well closed."

|

AFTER VIEWING THE UNION LINE FROM THE BURTON FARM, JACKSON TOOK A MOMENT

TO SCRIBBLE THIS DISPATCH TO ROBERT E. LEE. THREE HOURS LATER HE

ATTACKED. (BL)

|

|

|