|

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

HOOKER RETREATS: MAY 5-6, NIGHT

Having eliminated the threat to his rear. Lee returns to

Chancellorsville to finish off Hooker but the Union commander declines

to give battle. Learning of Sedgwick's retreat and anticipating an

attack on his own line, Hooker instead orders the army to withdraw

across U. S. Ford. Meade's corps covers the retreat.

|

Driving rain soaked Union soldier's tramping toward the pontoon

bridges at United States Ford on May 5. Many grew despondent when they

realized Hooker meant to abandon the field. A soldier in the 141st

Pennsylvania voiced a common sentiment: "We supposed that our men still

held the heights of Fredericksburg—that although we were lying

comparatively quiet our men were doing a big thing elsewhere," he

commented. "And then the thought, must we lose this battle? Have these

brave comrades who have fought so bravely and died at their post died in

vain?" Confederates such as cartographer Jedediah Hochkiss marveled that

Hooker had given up so easily. After a day of taking measurements in the

area for a map of the campaign, Hotchkiss recorded in his journal on May

12, 1863, that he "had no idea the enemy were so well fortified and

wonder they left their works so soon." Such speculation lay ahead as

unit after unit of the Army of the Potomac trudged across their pontoons

on May 5-6. By 9:00 A.M. on Wednesday the sixth, the last Federals had

reached the left bank of the Rappahannock. Union engineers pulled the

soggy pontoon bridges from the Rappahannock, bringing to an end the

latest—and in many ways the most promising—Union operation

against Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia.

|

DESPITE RISING WATERS THAT THREATENED TO SWEEP AWAY ITS PONTOON BRIDGES,

THE ARMY OF THE POTOMAC MADE IT SAFELY ACROSS U.S. FORD BY DAWN, MAY 6.

IT WOULD LIVE TO FIGHT ANOTHER DAY. (BL)

|

|

AS A RESULT OF THE BATTLE, HOOKER'S REPUTATION PLUMMETED. "HE WENT UP

LIKE A ROCKET," COMMENTED ONE OFFICER, "AND CAME DOWN LIKE A STICK."

(BL)

|

When Abraham Lincoln learned of the retreat, he began to pace

nervously, moaning, "My God! My God! What will the country say?"

|

News of Chancellorsville reverberated through the North and the

Confederacy. When Abraham Lincoln learned of the retreat, he began to

pace nervously, moaning, "My God! My God! What will the country say?

What will the country say?" Editor Horace Greeley of the New York

Tribune reacted almost identically: "My God!" he said, holding the

telegram that announced the chilling news, "it is

horrible—horrible; and to think of it, 130,000 magnificent

soldier's so cut to pieces by less than 60,000 half-starved

ragamuffins!" On the home front and within the Army of the Potomac,

various villains were put forward—O. O. Howard and his Germans for

being routed on May 2, John Sedgwick for failing to march with alacrity

on the third or to fight harder on the fourth, and of course Joseph

Hooker, whose blustering before the campaign had set him up for a

spectacular fall. Whispers suggested that the commanding general had

been drunk, a charge difficult to substantiate or deny from surviving

evidence.

Hooker sought to justify his own performance. A congratulatory order

to the army betrayed only the remotest connection to reality. "In

withdrawing from the south bank of the Rappahannock before delivering a

general battle to our adversaries," it read in part, "the army has given

renewed evidence of its confidence in itself and its fidelity to the

principles it represents." Hooker spoke with a group of officers in late

May, defending his decision to remain passive on May 4 with the

observation that he expected Lee to assault the Union works. He also

expressed anger toward Sedgwick at this gathering. "He was very bitter

against 'Uncle John,'" wrote a colonel from the First Corps who heard

the comments, "accusing him of being slow and afraid to fight; also of

disobeying orders directly." Offended by Hooker's statements, this

officer felt "shame for my commanding general, and indignation at the

attack on so true, brave, and modest a man as Sedgwick. Some officers in

the Army of the Potomac saw justice in Hooker's travails after

Chancellorsville pleased that the man who had pilloried Burnside after

Fredericksburg now gagged on a dose of his own medicine.

|

A CURRIER AND IVES LITHOGRAPH OF THE BATTLE OF CHANCELLORSVILLE, MAY 3,

1863. (LC)

|

Most reaction south of the Mason-Dixon Line mirrored that of

Catharine Ann Devereux Edmondston, a North Carolina woman who described

relatives on May 10 "full of our Victory, which all admit to be a

glorious one, throwing that of Fredericksburg in the shade." As did many

other happy Confederates, she alluded to numbers and the fact that

Chancellorsville represented but the latest in a series of Lee's

triumphs: "Hooker is terribly beaten & that too by a force one half

his own. Off with his head & let him too take a house in N Y &

join the clique of beaten Generals—'Beaten Row' or 'Vanquished

Square' or 'Conquered Place' and call it as their taste may be."

Jefferson Davis thanked Lee and his army "in the name of the people . .

. for this addition to the unprecedented series of great victories which

your army has achieved," Lee's veterans joined many civilian

counterparts in redoubling their faith in a commander seemingly able to

accomplish the impossible. If the Army of Northern Virginia could

vanquish Hooker's "finest army on the planet" with Longstreet and two

full divisions absent, what could prevent its carrying the nascent

Southern nation toward independence?

|

STONEWALL JACKSON'S LAST DAY

After being wounded at Chancellorsville, Stonewall Jackson was

carried behind the lines to the Wilderness Tavern, where Doctor Hunter

H. McGuire removed his injured left arm just two inches below the

shoulder. The general was then taken by horse-drawn ambulance a distance

of 27 miles to Guinea Station on the R. F. & P. Railroad, where be

would rest before continuing on to Richmond. For six days he remained at

Guinea, occupying the farm office of Thomas Chandler's home,

"Fairfield." At first, he showed signs of recovery, but later in the

week pneumonia set in and by Sunday, May 10, doctors gave up all hope of

his recovery. In the following account, Dr. McGuire recalled the

general's quiet faith and courage in the final hours of his life.

"About daylight, on Sunday morning, Mrs. Jackson informed him that

his recovery was very doubtful, and that it was better that he should be

prepared for the worst. He was silent for a moment, and then said: 'It

will be infinite gain to be translated to Heaven.' He advised his wife,

in the event of his death, to return to her father's house, and added,

'You have a kind and good father, but there is no one so kind and good

as your Heavenly Father.' He still expressed a hope of his recovery, but

requested her, if he should die, to have him buried in Lexington, in the

Valley of Virginia. His exhaustion increased so rapidly, that at eleven

o'clock, Mrs. Jackson knelt by his bed, and told him that before the sun

went down, he would be with his Saviour. He replied, 'Oh, no! you are

frightened, my child; death is not so near; I may yet get well.' She

fell over upon the bed, weeping bitterly, and told him again that the

physicians said there was no hope. After a moment's pause he asked her

to call me. 'Doctor, Anna informs me that you have told her that I am to

die to-day; it is so?' When he was answered, he turned his eyes towards

the ceiling, and gazed for a moment or two, as if in intense thought,

then replied, 'Very good, very good, it is all right.' He then tried to

comfort his almost heart-broken wife, and told her he had a good deal to

say to her, but he was too weak. Colonel Pendleton came into the room

about one o'clock, and he asked him, 'Who was preaching at headquarters

to-day?' When told that the whole army was praying for him, he replied,

'Thank God—they are very kind.' He said: 'It is the Lord's Day; my

wish is fulfilled. I have always desired to die on Sunday.'?

|

AFTER THE AMPUTATION OF HIS LEFT ARM, JACKSON WAS CARRIED 27 MILES TO

GUINEA STATION. HE SPENT THE LAST WEEK OF HIS LIFE AT FAIRFIELD, THE

HOME OF THOMAS CHANDLER. (NPS)

|

His mind now began to fail and wander, and he frequently talked as if

in command upon the field, giving orders in his old way; then the scene

shifted, and he was at the mess-table, in conversation with members of

his staff; now with his wife and child; now at prayers with his military

family. Occasional intervals of return of his mind would appear, and

during one of them, I offered him some brandy and water, but he declined

it, saying, 'It will only delay my departure, and do no good; I want to

preserve my mind, if possible, to the last.' About half-past one, he was

told that he had but two hours to live, and he answered again, feebly,

but firmly, 'Very good, it is all right.' A few moments before he died

he cried out in his delirium, 'Order A. P. Hill to prepare for action!

pass the infantry to the front rapidly! tell Major Hawks'—then

stopped, leaving the sentence unfinished. Presently, a smile of

ineffable sweetness spread itself over his pale face, and he said

quietly, and with an expression, as if of relief, 'Let us cross over the

river, and rest under the shade of the trees;' and then, without pain,

or the least struggle, his spirit passed from earth to the God who gave

it."

|

ON MAY 10, JACKSON BREATHED HIS LAST. HIS FINAL WORDS WERE, "LET US

CROSS OVER THE RIVER, AND REST UNDER THE SHADE OF THE TREES." (NPS)

|

|

Lee took a far more subdued view. "At Chancellorsville we gained

another victory; our people were wild with delight—" he stated

shortly after Gettysburg. "I, on the contrary, was more depressed than

after Fredericksburg; our loss was severe, and again we had gained not

an inch of ground and the enemy could not be pursued." Indeed,

Chancellorsville was a bittersweet success. Lee lost nearly 13,000 men

killed, wounded, and missing—22 percent of his entire army. In

contrast, the Union butcher's bill was relatively much lower, slightly

more than 17,000 casualties that amounted to 13 percent of Hooker's

force. Worst of all for Lee and the Confederacy, Stonewall Jackson died

on May 10 of complications arising from injuries he received while being

carried from the field on May 2. Lee would never find an adequate

replacement for the strange and compelling genius he called the "great

and good" Jackson.

Although he viewed Chancellorsville as an empty victory, Lee took

away from it even deeper admiration for his soldiers. "With heartfelt

gratification," he announced in General Orders No. 59 on May 7, 1863,

"the general commanding expresses to the army his sense of the heroic

conduct displayed by officers and men during the arduous operations in

which they have just been engaged." The result, asserted Lee, entitled

the army "to the praise and gratitude of the nation." Perhaps

Chancellorsville convinced Lee that his men could overcome any odds.

Whether or not that was the case, his profound belief in their skill and

devotion manifested itself two months later in crucial decisions at

Gettysburg.

|

CANNONS AT HAZEL GROVE. (NPS)

|

|

LEE STANDING AT THE GRAVE OF STONEWALL JACKSON IN LEXINGTON, VIRGINIA.

(NPS)

|

Although it was the bloodiest battle to that stage of the Civil War,

Chancellorsville rapidly receded from the front pages as Lee marched

north in June. The eastern armies soon reached their fateful rendezvous

at Gettysburg, where unprecedented carnage pushed the events of early

May well into the shadows. Yet Chancellorsville retains a timeless

fascination as an example of what imaginative military leadership can

accomplish against daunting obstacles. Would a better Union general have

made Lee pay dearly for the risks he took? Perhaps so—but it was

Joseph Hooker who faced the Confederate paladin in the Wilderness of

Spotsylvania, and his personality looms as large in any modern

consideration of the campaign as it did in Lee's calculations at the

time. The men of the Army of the Potomac, who had fought so well on so

many fields only to be betrayed by their commanders, once again showed

robust devotion to duty at Chancellorsville. But the lion's share of

accolades must go to Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia, whose daring

and perseverance concocted a tactical victory of memorable proportion.

Chancellorsville capped a string of triumphs for Lee's army in Virginia

that nurtured among the Confederate citizenry an expectation of

continued success. That expectation in turn would sustain hopes for

Southern independence during two more years of grinding war.

|

CHANCELLORSVILLE BATTLEFIELD

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

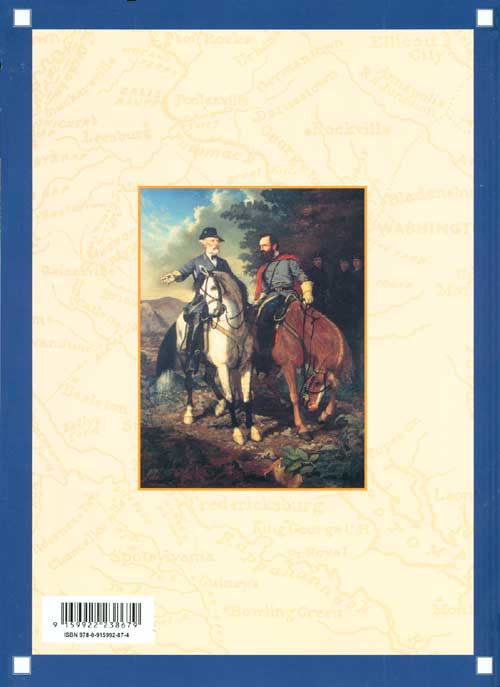

Back cover: Last Meeting of Lee

and Jackson, by Everett B. D. Julio, courtesy of The Museum

of the Confederacy, Richmond, Viriginia.

|

|

|