|

Colonial National Historical Park Virginia |

|

NPS photo | |

For in Virginia a plaine soldier that can use a pick-axe and spade is better than five knights.

—Capt. John Smith

JAMESTOWN

Dreams of finding wealth in a New World drew English settlers, backed by the Virginia Company of London, to Jamestown Island in 1607. Here you can walk the ground they cleared to build the original James Fort.

Powhatan, chief to the Native peoples who had lived here for thousands of years, was wary of the English. He offered them maize in trade, disappointing the company's directors, who hoped for gold. The directors then ordered the settlers to make glass, pottery, and iron wares, and cultivate mulberries for silk-making. Near the site of the original glass shop you can view craftsmen making glass wares similar to those of the 1600s. Early leaders like Captain John Smith organized a growing colony, while exploring the rivers and lands and encountering various other tribes.

When over 200 more English arrived, Powhatan refused to continue to supply maize. He ordered a siege that reduced the colonists to eating vermin in the winter of 1609-10. The death by starvation of many indentured workers (bound to seven- to nine-year terms of labor) created a labor crisis. The company found it hard to recruit people to a life sure to be hard and brief. In 1619, its treasurer Edwin Sandys proposed "the sending of maids [women]" and poor children to boost the population. It relaxed its most punitive laws, and allowed those who had completed their terms of indenture to purchase land.

The company approved the creation of a House of Burgesses, which met in 1619 at Jamestown Church. It was the first representative assembly in English-speaking North America. Although the colonial governor could veto decisions reached by his council and 22 elected burgesses, the colonists began to grow accustomed to having a say in their own destiny. Pause for a moment in the Memorial Church, built on the site of that monumental event in our history, and allow yourself to be transported in time.

Also in 1619, two English privateers landed and sold 20 to 30 captive Angolans at Point Comfort, planting the roots of slavery in the Virginia colony. At the New Town home site of planter-merchant William Pierce, archeologists are uncovering the story of a woman named Angelo or Angela. The only one of the first Africans whose name is known, she lived in the Pierce household in 1625.

Planters like Pierce grew tobacco, a labor-intensive cash crop. (John Rolfe is credited with introducing a profitable strain of the tobacco plant, as well as with marrying Pocahontas, one of Powhatan's daughters, which helped maintain peace for a time.)

As the need for labor grew, the planters turned to a race-based system of lifelong, hereditary enslavement. Many African Americans who had earlier lived as free people—through acceptance of Christianity, the free status of one or both parents, or their place of birth—lost their rights. After 1662, children born to enslaved mothers were permanently enslaved, even if their fathers were free men. In 1705, the assembly adopted a Slave Code.

Amongst the rest of the plantations all this summer little was done, but securing themselves and planting tobacco, which passes there as current silver.

—Capt. John Smith, 1622

Hunger, survival, luck, love, and greed brought different cultures to Jamestown Island. Free, enslaved, and indentured people mixed here and gradually merged into a new but imperfect society.

Jamestown's legacy includes representative government, but also slavery, a brutal institution that spread through the colonies. At Yorktown, Virginia colonists fought in the last major battle of the Revolution.

I heard with pleasure the speaking of the cannon at York.

—Comte de Grasse to Gen. George Washington

YORKTOWN

In 1691 the General Assembly authorized the Act for Ports, creating towns with wharfs, docks, and counting houses. The towns would aid the British colonial government by supporting trade, collecting taxes for the king on goods imported from England, and inspecting and recording outgoing cargo.

One such port was Yorktown. It occupied 50 acres on the Virginia Peninsula's north side. It had a deep, protected harbor navigable by increasingly large trade vessels. Its more than 200 buildings included a custom house, church, taverns, and stately brick homes. Until the mid-1700s, Yorktown thrived.

Taxes to fill the exchequer's coffers were the reason for Yorktown's founding—but also why some Yorktown citizens joined the boycotts of English imports that gained momentum after England imposed the Sugar and Stamp Acts in the 1760s. War between Great Britain and its American colonies began in the spring of 1775.

After the Continental Army's defeat of the British at Saratoga in 1777, France signed military and commercial alliances with the United States. The American Revolution became a world war.

The British responded with a new focus on holding the southern colonies where they believed loyalist support to be concentrated. After success in Georgia and South Carolina, Lord Charles Cornwallis eyed North Carolina and Virginia's wealthy plantations and ports. As fall 1781 neared, his army began to look for suitable winter quarters. In August Cornwallis and 8,300 men occupied Yorktown.

General George Washington and his French allies under the Comte de Rochambeau saw the occupation as an opportunity. The new United States lacked its own navy, but France provided a fleet of 26 warships, commanded by the Comte de Grasse, that kept the British navy from rescuing or resupplying Cornwallis. In late August the French disabled six British ships and blockaded the Chesapeake Bay, isolating Cornwallis and his men. Against this backdrop, the combined American and French forces initiated the siege of Yorktown, which left "the Lord . . . shut up within his fortifications." Later Cornwallis would write, "I never saw this post in a favorable light."

On October 17, 1781, surrounded, with all escape routes cut off, his forces exhausted by the bombardment and siege and depleted by smallpox, Cornwallis sent a letter to Washington. He proposed terms of surrender for the forces under his command, but claimed illness on October 19, 1781, the day of surrender, avoiding having to face George Washington and his troops. Impoverished by fighting many enemies at once, the British government agreed to peace talks, leading to the end of the war in early 1783. The United States had won its independence. Today you can walk Surrender Field, where the British army laid down its arms, and visit some of the colonial era homes that survived the siege of 1781.

1607 Three wooden ships, Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery, carry 104 Englishmen across the Atlantic to a tiny island in a river they call the James. Within days, Powhatan Indians, whose chiefdom is at Werowocomoco, attack. The English build a triangular fort for defense. John Smith becomes their leader.

1608 "First Supply" of skilled tradespeople increases the fort's small population.

1609 Chief Powhatan orders a siege of James Fort. It leads to the "Starving Time" that kills all but 60 colonists by winter's end.

First Anglo-Powhatan War.

1610 John Rolfe introduces tobacco, probably from the Caribbean. He finds a strain that will flourish in Virginia's soil, a "rich, blackish mould."

1614 Pocahontas, daughter of Chief Powhatan, marries Rolfe in Jamestown Church; a 7-year peace results.

1619 First elected legislative assembly in the western hemisphere meets at Jamestown Church; its 3rd Petition recommends bringing unmarried women to the colony.

20 to 30 Africans captured from a Portuguese war ship are forcibly landed at Point Comfort on Chesapeake Bay.

1622 Chief Opechancanough leads massacre of over 350 English outside James Fort.

Second Anglo-Powhatan War.

1644 Third Anglo-Powhatan War.

1676 Tobacco prices drop. England's failure to protect trade vessels against attacks at sea, increased taxes, and policies toward Indians create dissent among some colonists.

Nathaniel Bacon leads populist rebellion against Colonial Governor William Berkeley; burns Jamestown.

1691 Through an Act for Ports, the General Assembly establishes Yorktown, with wharfs and storehouses to support and monitor trade.

1699 Capital moves from Jamestown to Middle Plantation, later called Williamsburg.

1700 The Virginia Colony's population of enslaved African and West Indian people dramatically increases.

1705 General Assembly votes to create a race-based Slave Code that strips all rights from people of color.

1750s Yorktown thrives as a center for trade; population reaches 1,800.

1774 1st Virginia Revolutionary Convention; Thomas Nelson Jr., with "Inhabitants of York," throws tea overboard in Yorktown Harbor to protest British tea tax.

1776 Declaration of Independence. Nelson is one of 56 signers. The Revolution gains momentum.

1781 In the fifth year of the war, British Gen. Charles, Lord Cornwallis, occupies Yorktown with 8,300 men. Allied French and American armies surround and bombard the town, and destroy most it. After proposing terms for his 7,000 surviving men, Cornwallis surrenders on October 19, 1781. Britain recognizes American independence in January 1783. The war is officially over.

COLONIAL NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK

(click for larger maps) |

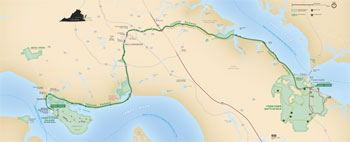

Includes most of Jamestown Island, Yorktown Battlefield, and Colonial Parkway, which connects them; Green Spring (open only for special programs); and Cape Henry Memorial. Congress authorized the park in 1930 and later designated the Captain John Smith Chesapeake and Washington-Rochambeau National Historic Trails that pass through park lands and waterways. In 1933 the Department of War transferred Yorktown National Cemetery, with over 2,000 Civil War interments, to the park.

COLONIAL PARKWAY

From I-64, exit west to Jamestown Island or east to Yorktown for scenic views of the historic Virginia Peninsula. Driving west, you'll pass wide beaches and a rare community of bald cypress and wax myrtle trees along the James River. Heading east, a mixed pine and hardwood forest forms a dense canopy over the Williamsburg to Yorktown segment. Within Yorktown Battlefield, the parkway winds through swamps and open fields where the French and Continental armies camped during the siege in 1781. Colonial National Historical Park includes 8,677 acres. About 6,000 acres provide habitat for native plants and wildlife.

JAMESTOWN

Jamestown Island is the original site of the first permanent English settlement in North America. Preservation Virginia acquired 22.5 acres of the island in 1893. The National Park Service purchased the remaining 1,500 acres in 1934. In 1994, Preservation Virginia began an archeological project, Jamestown Rediscovery, to find the remains of the original James Fort, ca. 1607-24, long thought lost to the James River. The discovery of the fort in 1994 and the excavations since revealed thousands of artifacts and greatly increased our understanding of this first chapter in American history.

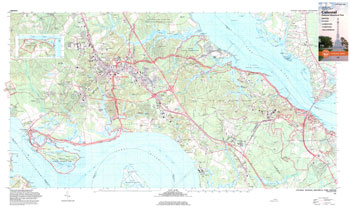

YORKTOWN BATTLEFIELD

| Battlefield Tour | Allied Encampment Tour |

|---|---|

|

British Inner Defense Line

Grand French Battery Second Allied Siege Line (Yorktown National Cemetery) Redoubts 9 and 10 Moore House Surrender Field |

American Artillery Park

Gen. Washington's HQ French Cemetery French Artillery Park French Encampment Area Untouched Redoubt |

"Houses [were] pulled down, others pulled to pieces for fuel" when French and Continental armies bombarded Yorktown to end the British occupation. Nelson House stayed largely intact. Thomas Nelson Jr. (1738-89) served in the Continental Congress and state legislature and signed the Declaration of Independence. He commanded the Virginia militia during the 1781 bombardment.

Most of the original ornamental details also survived the Civil War and a 1920 renovation. The National Park Service acquired and restored Nelson House in the 1980s.

Source: NPS Brochure (2018)

Documents

A Note Concerning the York County Tobacco Warehouses before 1800 (Joseph C. Robert, 1937)

A Tryal of Glasse: The Story of Glassmaking at Jamestown (J.C. Harrington, 1972, ©Eastern National)

Archeological Excavations at Jamestown, Colonial National Historical Park and Jamestown National Historic Site, Virginia (John L. Cotter, 1958)

Air Quality Management Plan: A Prototype, Colonial National Historical Park NPS Natural Resources Report NPS/NRAQD/NRR-91/01 (Sandra Manter, Charles Rafkind, Erik Hauge and John Karish, June 1991)

Air Quality Management Plan for Colonial National Historical Park (Sandra Manter, Charles Rafkind, Erik Hauge and John Karish, June 1991)

Coastal Hazards & Sea-Level Rise Asset Vulnerability Assessment for Colonial National Historical Park NPS 333/154061 (K. Peek, B. Tormey, H. Thompson, R. Young, S. Norton, J. McNamee and R. Scavo, February 2017)

Colonial Parkway Context: History of the American Parkway Movement, National Park Service Design and Historic Preservation Contexts (LANDSCAPES, November 1998)

Cultural Landscape Report for Colonial Parkway, Part I: Site History, Existing Conditions & Analysis, Colonial National Historical Park (LANDSCAPES, November 1997)

Cultural Landscape Report for the Nelson House Grounds, Colonial National Historical Park (Bryne D. Riley, John Auwaerter and Paul Fritz, 2011)

Cultural Landscape Report for the Nelson House Grounds, Colonial National Historical Park — Volume 2: Treatment (Danielle D. Desilets, 2024)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Green Spring, Colonial National Historical Park (2003)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Nelson House, Colonial National Historical Park (2012)

Draft General Management Plan/Environmental Assessment, Colonial National Historical Park, Virginia (July 1992)

Excavations at Green Spring Plantation (Louis R. Caywood, May 25, 1955)

Flowering Plants of the Colonial National Historical Park (Chester F. Phelps, June 1937)

Foundation Document, Colonial National Historical Park, Virginia (May 2018)

Foundation Document Overview, Colonial National Historical Park, Virginia (May 2018)

General Management Plan - Colonial National Historical Park (September 1993)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Colonial National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2016/1237 (T.L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, June 2016)

Historic American Engineering Record

Colonial National Monument Parkway (Colonial Parkway) HAER No. VA-48 (Joseph P. Meko, 1988)

Colonial National Monument Parkway, Navy Mine Depot Overpass (Mine Depot Overpass) HAER No. VA-48-A (Joseph P. Meko, 1988)

Colonial Parkway, Parkway Drive Bridge (Route 163 Bridge) HAER No. VA-48-AA (Michael G. Bennett, 1995)

Colonial National Monument Parkway, Capitol Landing Underpass HAER No. VA-48-B (Joseph P. Meko, 1988)

Colonial National Monument Parkway, C & O Railroad Underpass HAER No. VA-48-D (Joseph P. Meko, 1988)

Colonial National Monument Parkway, Williamsburg Tunnel HAER No. VA-48-C (Joseph P. Meko, 1988)

Colonial Parkway, Ballard Creek Culvert HAER No. VA-48-E (Michael G. Bennett, 1995)

Colonial Parkway, Bracken Pond Culvert HAER No. VA-48-F (Michael G. Bennett, 1995)

Colonial Parkway, Jones Mill Pond Dam HAER No. VA-48-G (Michael G. Bennett, 1995)

Colonial Parkway, Indian Field Creek Bridge HAER No. VA-48-H (Michael G. Bennett, 1995)

Colonial Parkway, Halfway Creek Bridge HAER No. VA-48-K (Michael G. Bennett, 1995)

Colonial Parkway, Mill Creek Bridge HAER No. VA-48-N (Michael G. Bennett, 1995)

Colonial Parkway, Isthmus Bridge HAER No. VA-48-P (Michael G. Bennett, 1995)

Colonial Parkway, Route 199 Bridge (Bridge at Millers Crossing) HAER No. VA-48-Z (Michael G. Bennett, 1995)

Colonial National Historical Park Roads and Bridges (Yorktown to Jamestown Island) HAER No. VA-115 (Michael Gallagher Bennett, 1995)

Historic American Landscapes Survey

Colonial Parkway (Jamestown Island-Hog Island-Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail District) HALS No. VA-74 (andra DeChard, July 10, 2017)

Yorktown Battlefield (Jamestown Island-Hog Island-Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail District)) HALS No. VA-77 (Sandra DeChard, July 10, 2017)

Historical Information, Colonial National Historical Park, Yorktown, Virginia (September 1968)

Impacts of Visitor Spending on the Local Economy: Colonial National Historical Park, 2001 (Daniel J. Stynes Ya-Yen Sun, January 2003)

Inventory of Mammals (Excluding Bats) of Colonial National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCBN/NRTR-2010/321 (Ronald E. Barry, Heather P. Warchalowski and Dana T. Strong, May 2010)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Colonial Parkway (Shaun Eyring and Phyllis Ellin, December 1999)

Green Spring (James Haskett and Brooke Blades, September 13, 1976)

Green Springs Historic District (Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Staff, February 1973)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Colonial National Historical Park, Virginia NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/COLO/NRR-2012/544 (Todd Lookingbill, Catherine N. Bentsen, Tim J.B. Curruthers, Simon Costanzo, William C. Dennison, Carolyn Doherty, Sarah Lucier, Justin Madron, Ericka Poppell and Tracey Saxby, June 2012)

Outline of Development, Colonial National Monument (National Historic Park) (1933)

Overview of Climate Change Adaptation Needs, Opportunities and Issues: Northeast Region Coastal National Parks NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NER/NRR-2014/789 (Amanda L. Babson, April 2014)

Paleontological Resources Inventory (Public Version), Colonial National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/COLO/NRR-2022/2361 (Mackenzie Chriscoe, Rowan Lockwood, Justin S. Tweet and Vincent L. Santucci, February 2022)

Ringfield Plantation, Colonial National Historical Park (Charles E. Hatch, Jr., September 1970)

Superintendent's Annual Reports: 2002 • 2003 • 2004

The Evolution of the Concept of Colonial National Historical Park: A Chapter in the Story of Historical Conservation (Charles E. Hatch, Jr., July 28, 1964)

The Green Spring Plantation Greenhouse/Orangery and the Probable Evolution of the Domestic Area Landscape (M. Kent Brinkley, December 31, 2003)

The History and Development of Colonial National Historical Park (Edward M. Riley, April 30, 1936)

Vegetation Classification and Mapping at Colonial National Historical Park, Virginia NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NER//NRTR-2008/129 (Karen D. Patterson, June 2008)

colo/index.htm

Last Updated: 06-Feb-2025