|

Crater Lake National Park: Ecology Of Elk Inhabiting Crater Lake National Park And Vicinity

|

|

|

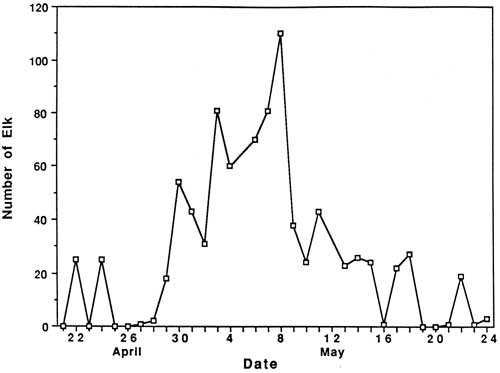

Results and Discussion Capture and Collaring Seventeen elk were trapped and immobilized in Upper Klamath Basin, primarily during spring 1985 (Appendix A). Eleven cow elk were successfully trapped and radio-collared; three yearling males were successfully ear-tagged, and three adult cow elk died during the capture process. Eighteen mg of succinylcholine chloride was sufficient to immobilize adult cow elk, whereas only 14-16 mg was administered to yearling cows and bulls. Deaths of three adult cow elk were related to trapping injuries or poor physical condition. Population Characteristics A total of 844 elk were observed during routine censuses in the Upper Klamath Basin between 22 April - 24 May 1985. Numbers of elk using pasturelands north and west of Seven Mile Road and Highway 62, respectively, were low in late April, gradually increased to a peak on 8 May, and decreased steadily until the third week in May (Fig. 1). Those data suggest a gradual arrival of spring migrants to the Upper Klamath Basin in late April and throughout the first week of May. Although timing of the arrival of elk to the Upper Klamath Basin undoubtedly varies among years, reflecting differences in spring weather and snowpack, our results suggest that trends of elk numbers in the Crater Lake area could perhaps be monitored by conducting intensive spring surveys of elk in pastures immediately to the south of CRLA in the Upper Klamath Basin.

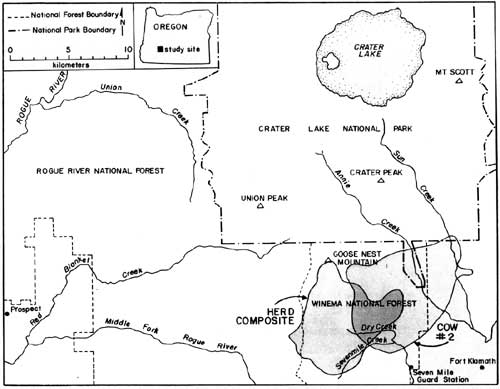

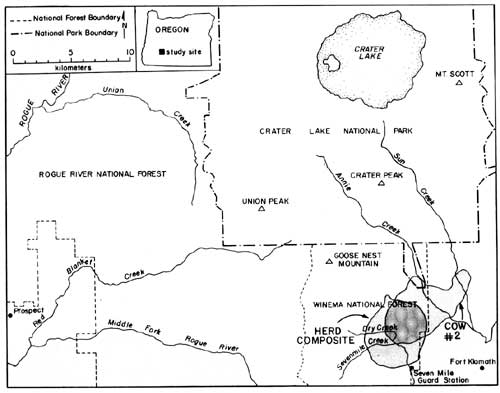

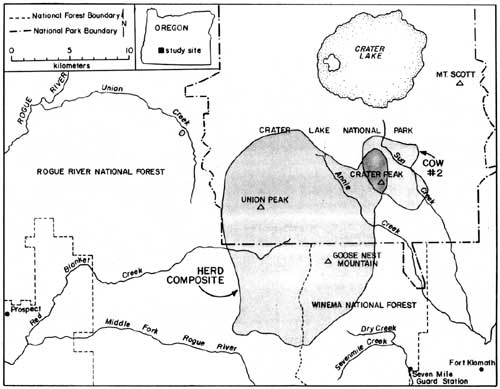

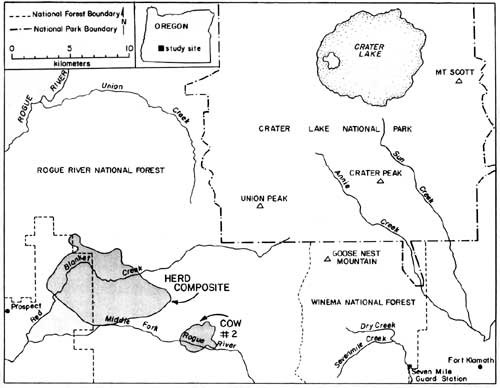

Reasons for the sudden decrease in elk observations following May 8th are unknown; however, it coincided with several important factors, including: (1) snow disappearance and greenup of adjacent forests and clearcuts, (2) increased rancher activities in pastures, (3) arrival of cattle in pastures, (4) increased wood cutting and recreational activities in surrounding areas, and (5) onset of calving. The rather abrupt arrival and dispersal of elk in the Upper Klamath Basin would place narrow seasonal constraints on any future elk monitoring activities in the Basin. Also, additional years of data would be necessary to assess year-to-year variability in elk numbers, and hence, the reliability of the trend index. A total of 81 elk wee classified as calves or cows on summer ranges within CRLA during 1986, and 220 were classified on spring range adjacent to the park during 1985. Calf production as estimated from summer counts was 55 calves per 100 cows, not accounting for neonates that might have died prior to summer. Such productivity appeared to be greater than average estimates of 27 calves per 100 cows obtained in CRLA during the 1970's (Hill 1976). Hill suggested that the earlier estimates may have been biased because many calves may not have been observed when only portions of herds were counted. This commonly occurs when calves form nursery groups on the perimeter of cow herds. If only groups that contained both cows and calves are counted, then production of calves during the 1970's averaged 60 calves per 100 cows, which as Hill (1976) pointed out, is near the biotic potential of an elk herd. Although productivity of elk herds in CRLA appears to be high, calf ratios obtained during spring 1985 (25:100) were typical of those found throughout western Oregon (Harper 1985, Witmer 1980) and Washington (Jenkins 1981, Smith 1980). Sequential counts of calves and cows obtained during summer and the following spring have frequently been used as indices of calf survivorship. Unfortunately, overwinter survival of calves cannot be compiled from our data because counts were obtained during the spring prior to, rather than following, the summer classification counts. However, assuming no large differences existed in calf production between 1985 and 1986, comparisons of calf ratios from summer 1985 (55:100) and spring 1985 (25:100) suggest large reductions in the abundance of calves may occur over winter. Although several authors have observed low calf survivorship in Roosevelt elk (Witmer 1982, Merrill 1985), additional intensive surveys of calf ratios on summer ranges, and on spring ranges south of the park will be needed to better understand herd dynamics in CRLA. Such surveys will be very difficult because all elk in each herd must be classified, not just the easily observable portions of herds. Seasonal Movements and Home Range Radio-collared elk in the Crater Lake ecosystem migrated between winter ranges on the west slope of the Cascades, spring ranges on the east side, and summer ranges on the Cascade Crest. Spring migrations averaged 35 km between winter range on the Rogue River National Forest and spring range on the Winema National Forest. Late-spring migrations to summer range within Crater Lake National Park added approximately 16 km to the total migration distance between winter and summer ranges. Seasonal ranges of radio-collared elk are shown in Figs. 2-6, and are described in greater detail below. Cow elk trapped during spring in the Upper Klamath Basin concentrated their activities along the eastern boundary of the Winema National Forest from Seven Mile Guard Station north to the park boundary. Elk arrived on spring range primarily between 20 April - 8 May during 1985, judging from the survey results (Fig. 1). During 1986, some radio-collared elk arrived on spring range as early as 1 April, and the majority had arrived by 21 April. Three late-comers did not arrive until sometime after 3 May. Telemetry data indicated that migration from winter to spring ranges was highly individualistic and occurred over at least a one-month period. Movements of radio-collared elk were generally quite predictable on spring range. Most elk used clearcuts and private pastures along the USFS boundary for late night and early morning foraging bouts, and retreated westward to forested hillsides by day. Movements of two radio-collared cows deviated from the norm. One cow (designated cow #2) departed during early May 1985 and occupied a spring range partially separate from the others along Annie Creek and Sun Creek near the park's panhandle (Fig. 2). Another cow, one of the early spring arrivals and the first elk trapped in 1985, traveled from Seven Mile Guard Station to a location 15 km west across the Cascade Crest, where she remained for 10 days before returning to spring range. Radio-collared elk used the same spring ranges both years (Figs. 2-3). Annual differences in the distribution of elk in 1985 and 1986 were related to the trapping effort in 1985 and the resulting differences in sampling schedules. In 1985, we did not begin actively radio-tracking elk until most elk were captured in late May. In 1986, all except one elk were already radio-collared when they arrived on spring range, and they were radio-tracked beginning in early April. Distribution patterns of radio-collared elk in 1986 delineate the spring range of CRLA elk, whereas data from 1985 represent the late-season transition to summer range and the distribution of collared elk during calving season. Primary calving grounds of CRLA elk were in the remote headwaters of Seven Mile Creek, Dry Creek and the surrounding areas.

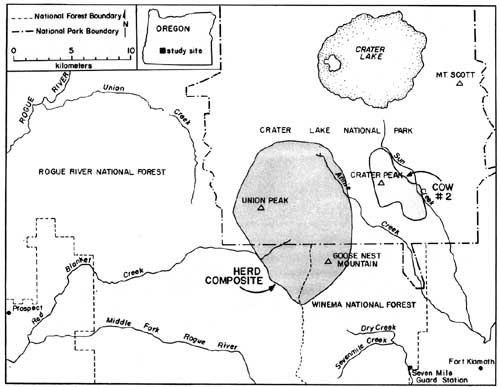

Migration of radio-collared elk from spring range to summer range consisted of gradual westerly and northerly upslope movements from the spring range. Migration to summer range had no discrete starting date, but distributions of elk began to shift in mid-May. Most elk were observed in the southern portion of their summer range near Goose Nest Mountain by 15 June 1985 and 1986. Radio-collared elk returned to the same summer ranges both years (Fig. 4-5). The majority of radio-collared elk summered from the south slopes of Goose Nest Mountain throughout the west side of the park north to Highway 62. Composite home ranges of radio-equipped elk were approximately 60-75% within the park. Cow #2 inhabited a summer range in the Crater Peak area separate from the remaining collared elk. These two home range areas, in the southwest and southeast of the park, correspond to two previously identified concentration areas of elk in CRLA (Manning 1974, Hill 1974). None of our radio-collared elk inhabited the northern half of the park, although previous investigators and our observations indicated lesser numbers of elk also inhabit the northern half of the park, primarily in the northwest. In October 1985, a radio-collared bull elk from another study, collared in the Umpqua drainage, was located in the northwestern corner of the park. He remained there until early November, then he joined elk from the southwest corner of the park and migrated with them to winter range.

Migration of radio-collared elk from summer to winter range varied between 1985 and 1986. During 1985, 10 inches of snow fell in mid-September causing elk to move downslope toward spring range for three days. They returned to summer range as the snow melted. During the third week in October, snow accumulated to two feet on summer range, again forcing elk to their spring range near Seven Mile Guard Station, where they remained for two weeks. The elk crossed over the Cascade Crest to the upper basins of Red Blanket Canyon in early November, and moved slowly down Red Blanket Creek arriving on winter range in mid-November (Fig. 6). Cow #2, from the Crater Peak area, remained on spring range near Annie Creek for two weeks and then migrated through 4-5 feet of snow on the Cascade Crest down the Middle Fork of the Rogue River between 25-29 November.

During 1968, early winter storms deposited 54" of snow in September and drove nine of eleven elk down Red Blanket Creek directly to the winter range. Subsequent warm weather and snowmelt allowed radio-collared elk to disperse widely back on summer range within CRLA. They may also have returned to their summer range due to hunting pressure after this heavy snow. The elk again returned to their winter range for the season after heavy snow in October, 1986. Winter ranges of most collared elk were located at elevations between 2800' - 4000' at the mouth of Red Blanket Canyon, near its juncture with the Rogue Valley. During November 1955, 1-2 feet of snow forced the elk onto Red Blanket floodplain near Prospect. As the snows melted, the elk concentrated on the bench known as Buck Flats. This lies between the mouth of the Middle Fork of the Rogue and the mouth of Red Blanket Creek. They also moved up to the bench north of the mouth of Red Blanket Creek. Snowpack was light to absent during the winter of 1985-1986, and the elk remained above the floodplain moving upward into the old-growth forests near Bessie Rock during March and before spring migration. Two radio-collared elk, one of which was number 2 from the Crater Peak Area, wintered up the Middle Fork of the Rogue Valley (Fig. 6). Seasonal Habitat Use Spring Availability and use of habitats were evaluated within the composite home range of elk during spring 1986. The composited spring range of elk consisted of 83% silviculturally managed forest, 11% managed pasture, and 6% non commercial or other forest types (Table 1). Shelterwood harvesting was the most prevalent cutting prescription, although clearcuts which were common in lodgepole pine forests covered approximately 6% of the spring range. The majority of forests were dominated by white fir and lodgepole pine. Radio-collared elk used many vegetation classes in proportion to their availability during spring (Table 1). White fir forests were the only cover type preferred by elk. White fir stands corresponded primarily to densely-stocked stands of medium-sized sawtimber, which correspondingly were also selected. Radio-collared elk avoided forest/pasture communities, which were forests within the pasture fenceline. Those stands were used intensively as bedding grounds by cattle and contained highly trampled understories. As a general diurnal pattern, elk were found in pasture, clearcuts, or partially cut stands during early morning and evening feeding periods, and they retreated to hillside forests, mainly densely-stocked stands of white fir, from mornings to afternoons. Such forests may have provided elk both with seclusion from high levels of human disturbance associated with roadways, and thermal protection from high mid-day temperatures that are common to the region.

Summer High elevation summer ranges primarily consisted of Shasta red fir and mountain hemlock/red fir forests (Table 2). A variety of other less extensive forest types comprised the remainder of the composite home range. During both summers, elk used red fir forests less than expected on the basis of availability and mountain hemlock/red fir forests significantly more than expected. Although used less than availability, red fir forests still contained an average of 22% of all the elk observations on summer range and should, together with mountain hemlock/red fir, be considered important components of the park habitat. Such forests contain locally dense patches of smooth woodrush, which may be important elk forage on CRLA ranges (Hill 1974). A variety of lodgepole pine communities were selected or were used in proportion to availability and were important elk habitats in the southern part of the park.

Winter Silviculturally managed forests in a variety of age- and size-classes made up more than 95% of the composited home range of elk in the Rogue Valley (Table 3). Clearcuts, less than 20 years old, primarily in the shrub-sapling developmental stage, comprised nearly 17% of the winter range. The pole stage of forest development, 21-60 years post-logging, made up 28% of the winter range. Pole stages corresponded to stands that were classed as either elk hiding cover or as hiding cover plus foraging area. A variety of sawlog and silviculturally overmature timber classes comprised the majority of the remaining winter range. Most of those forests were classed as elk thermal cover.

Elk demonstrated a clear preference for both hiding cover and optimal cover on winter range. Optimal cover, so designated because it provides both optimum cover and foraging values during severe winter weather, made up a very small proportion of the winter range, but received high use by elk. The winter of this study was mild, and snow accumulations rarely exceeded more than 4" from December to spring. Optimal cover may have even greater importance as elk habitat during severe winters. Foraging areas and stands of mixed hiding cover and foraging areas were neither preferred nor avoided by elk, but together they received high use (>60%). The close agreement between the availability (50%) and use (60%) of foraging areas by elk suggests that they may exist currently in a nearly optimum proportion of the winter range to satisfy forage requirements of the population. High preference of cover relative to forage, however, suggests that cover values may currently be more limiting to elk than forage. Creation of new foraging areas will be necessary to sustain wintering elk populations as the current foraging areas succeed to hiding and thermal cover. We suspect that the greatest challenge facing integrative forest and elk habitat management on this winter range in the future will be in providing replacement foraging areas without further diminishing important cover values. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

crla/ecology-elk/elk3.htm

Last Updated: 11-Aug-2016