.gif)

MENU

The Wawona Hotel and Thomas Hill Studio

Yosemite

Bathhouse Row

Hot Springs

Old Faithful Inn

Yellowstone

LeConte Memorial Lodge

Yosemite

El Tovar

Grand Canyon

M.E.J. Colter Buildings

Grand Canyon

Grand Canyon Depot

Grand Canyon

Great Northern Railway Buildings

Glacier

Lake McDonald Lodge

Glacier

Parsons Memorial Lodge

Yosemite

Paradise Inn

Mount Rainier

Rangers' Club

Yosemite

Mesa Verde Administrative District

Mesa Verde

Bryce Canyon Lodge

Bryce Canyon

The Ahwahnee

Yosemite

Grand Canyon Power House

Grand Canyon

Longmire Buildings

Mount Rainier

Grand Canyon Lodge

Grand Canyon

Grand Canyon Park Operations Building

Grand Canyon

Norris, Madison, and Fishing Bridge Museums

Yellowstone

Yakima Park Stockade Group

Mount Rainier

Crater Lake Superintendent's Residence

Crater Lake

Bandelier C.C.C. Historic District

Bandelier

Oregon Caves Chateau

Oregon Caves

Northeast Entrance Station

Yellowstone

Region III Headquarters Building

Santa Fe, NM

Tumacacori Museum

Tumacacori

Painted Desert Inn

Petrified Forest

Aquatic Park

Golden Gate

Gateway Arch

Jefferson National Expansion

|

Architecture in the Parks

A National Historic Landmark Theme Study |

|

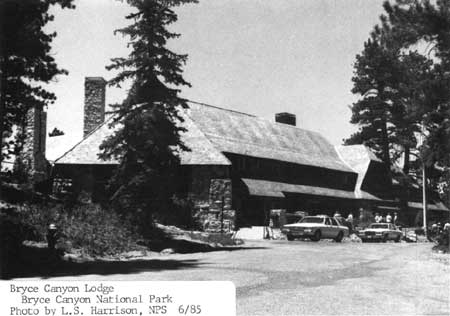

Bryce Canyon Lodge, Bryce Canyon NP, 1985.

(Photo by L.S. Harrison)

Bryce Canyon Lodge and Deluxe Cabins

| Name: | Bryce Canyon Lodge and Deluxe Cabins |

| Location: | Bryce Canyon National Park |

| Agency: | National Park Service Rocky Mountain Regional Office |

| Condition: | Good, altered, original site |

| Classification: | District, public, accessible (restricted), hotel |

| Builder/Architect: | Gilbert Stanley Underwood |

| Dates: | 1925-present |

DESCRIPTION

Bryce Lodge and its 15 deluxe cabins are on a mesa top about one-eight of a mile from the rim of the canyon. The Lodge and deluxe cabins are the most architecturally significant structures of a larger National Register district incorporating the remaining standard cabins, dormitory, recreation hall, and historic utility buildings. Only the Lodge and deluxe cabins are proposed for National Landmark status.

The Lodge is a two-story stone and exposed frame structure. The building has an irregularly-shaped plan. The original core of the building dating from 1924 is the central portion which is generally rectangular in plan. The north and southeast wings and a small addition to the central portion were added in 1926. A long portico which runs more than the length of the lobby serves as the main entrance to the structure. The portico has paired log columns that support a 52-foot long log beam, and is paved with bricks in a pattern repeated on entrance ramps to the north and south of the portico. The steeply pitched roofs have clipped gables and long shed dormers that break up the roof form. The roofs are finished with cedar shingles in a wavy pattern. This recent roof finish matches the original in material and pattern. The wood siding and exposed frame are painted dark brown. The highly textured stonework has mortar joints sunken back about three inches from the stone face.

The first floor of the lodge contains the lobby with the registration desk and adjacent offices, a small post office, the dining room, and auditorium known as the recreation room, the gift shop, the kitchen, and various storage and utility areas. The exposed wood columns in the lobby are milled timbers with brackets of an arts-and-crafts design that support large wood beams. The fireplace at the north end of the lobby is of roughly coursed rubble masonry. Lobby furnishings are not original. The dining room north of the lobby has a fireplace at its north end, and exposed flat trusswork like the trusswork in the kitchen. The fireplace has an opening in the shape of a pointed arch, and is of random rubble masonry. The gift shop south of the lobby has exposed roof trusses and decking, and horizontal siding on the walls. Roof trusses and the steep pitch of the roof are also exposed in the auditorium. Additional features of the room include wrought-iron chandeliers, a roughly coursed rubble masonry fireplace, and a maple parquet floor. The original stage remains on the east end of the room.

The lodge basement contains mechanical equipment for the building. A new parking area has been added to the rear of the building. Service entrances and loading docks at the rear of the building have at least several additions.

The Lodge has undergone many changes through the years. Plumbing and kitchen equipment have been updated periodically. Some partitions around the lobby area have been moved to accommodate changing functions through the years, particularly during the 1950s. The barbershop adjacent to the lobby was converted into a soda fountain. The curio shop and offices received additional space when a small portion of the auditorium was enclosed. Picture windows were installed in the dining room and curio shop. Also during the 1950s the road and ramp area at the front entrance were widened to accommodate more traffic and larger vehicles, and fire escapes were added to the north and west sides of the lodge. The plaza at the main entrance to the lodge was redesigned and enlarged in 1979 at the same time wheel chair ramps and guard rails were added. Other changes have been of a cosmetic and non-structural nature and are removable or reversible. On the interior many of the finishes have been re done with modern materials. The ceiling in the lobby, for instance is covered with acoustical tile, and the floor has newer carpeting. The chandeliers in the lobby are of modern design. Sliding aluminum windows in the second-story dormer replaced the original wooden sashes. A new lighting system has been suspended from the trusswork in the gift shop. Some of the original hickory and wicker furnishings of rustic design are in storage at the park. Plans are underway to reverse many of the architecturally incompatible changes and to restore the building's public spaces and exterior to their historic appearances. Despite the changes the building retains considerable original character.

The deluxe cabins are grouped to the southeast of the main lodge building and date from about 1929. Five of the cabins are quadruplexes; ten are duplexes. The smaller scale, natural materials, and siting in a pine grove below the lodge building make them fit with the surrounding natural and architectural environments. The rubble masonry chimneys alternate with stone corner piers on the exterior. The rubble masonry is highly textured, but more so in the quadruplexes where the mortar is often sunk back four inches or more from the stone face. Filling in between the stone piers and chimneys is log slab siding set horizontal on the main walls and vertical in the gable ends. The log slabs are separated from each other by a chinking of cement mortar, giving the buildings a striped appearance and adding to the visual interest of the structures. The log-slab siding on the duplex units retains its bark. The siding on the quadruplexes was peeled prior to installation. The steeply pitched gable roofs are finished with cedar shingles set in a wavy pattern like those of the main lodge. The original shingles were painted green, but these replacement shingles retain their natural finish. Rustic porches of log framework with peeled log railings shelter the separate entrances to the units.

On the interiors the original stone fireplaces and original panelling remain. The roof structure originally exposed in some of the cabins remains so. Baseboard heat has been added to the rooms and the fireplaces now burn gas piped into them. Bathrooms, furnishings, and interior cosmetic finishes have been updated periodically. The concrete walkways among the cabins was added during the 1970s during a waterline replacement project. The new walkways follow the same paths as the original but are slightly wider.

The deluxe cabins have undergone little exterior change with the exception of the aluminum frame windows added in 1983-84. On the interior the changes have been cosmetic and the principal architectural features remain.

Although the original complex has had some loss of integrity as a district because of the removal of the budget cabins and planned removal of most of the standard cabins, the Lodge and deluxe cabin.s retain their original character.

STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE

Bryce Lodge and deluxe cabins are the work of master architect Gilbert Stanley Underwood and are excellent pieces of the type of rustic architecture encouraged by the National Park Service and built by the railroads. This architecture, based on the use of onsite materials and detailing that made the buildings look as if they had been constructed by craftsmen with primitive hand tools, served several purposes. From the Park Service point of view the buildings provided a necessary visitor service--in this instance lodging--in structures that were highly compatible with the surrounding landscape in materials, scale, massing, and design. From the railroad's point of view, the buildings provided visitor services, but did so with a definite style that created a strong image and a strong sense of place. By enhancing the scenic qualities of Bryce Canyon and the other stops on the "U.P. Loop" through a noteworthy architecture, the Union Pacific Railroad was hoping to increase ticket sales and thereby compete more readily with other railroads offering similar services and experiences at Yellowstone, or Glacier, or the south rim of the Grand Canyon. Although the buildings' primary significance is architectural, they are of regional significance in the categories of transportation and tourism as part of the Union Pacific Railroad/Utah Parks development in Utah and northern Arizona. This is the last of the Utah Parks Company developments in Utah retaining high standards of architectural integrity.

Stephen Mather, first Director of the National Park Service proposed Bryce Canyon as a state park in 1921, and this proposal was accepted by the Utah legislature. Three years later when the state had done nothing to develop the area Mather concurred with establishing the area as a national monument under management of the U.S. Forest Service, and finally in 1930 as a national park. Even during its forest service times the park service reviewed all development plans for the area. At the same time that the state and federal governments were considering the tourism potential and scenic qualities of the area, the Union Pacific Railroad was considering a small expansion of a spur line from their main line in Lund, Utah, to Cedar City. The spur could serve the dual purposes of moving freight--particularly foodstuffs and iron ore--out to the main line from Cedar City while increasing passenger traffic to Cedar City and the loop of parks and monuments within driving distance. The spur could be a lucrative venture in increasing both passenger and freight traffic on their main line. By promoting tourism and providing accommodations the Railroad hoped to lure passenger traffic away from the Santa Fe Railway, the Great Northern, and even the Canadian Pacific which had established connections to parks and built resorts in those areas. [1]

To meet the needs of the tourism industry the Railroad formed the Utah Parks Company, the stock of which was held primarily by a Union Pacific subsidiary. The company was chartered to provide accommodations at the park and monument destinations and to provide transportation to those areas from Cedar City. In 1923 the company hired architect Gilbert Stanley Underwood of Los Angeles to design their Lodge at Zion and to choose the site for the Bryce Lodge.

Underwood came to the Union Pacific with a strong working background and degrees from both Yale and Harvard. Underwood began his career as an apprentice in Los Angeles to several important California architects who worked in styles from Beaux-Arts classicism to Mission Revival. After twelve years he returned to school and finished a Bachelor's degree at Yale and then went on to Harvard for his Master's. He returned to Los Angeles and set up an architectural office. Some of his early designs were for the core park service development in the Yosemite Valley. Although his designs were rejected for a variety of reasons, Stephen Mather, Horace Albright, and members of the early "landscape" staff such as Underwood's friend Daniel Hull, were impressed with his work and may have recommended him for the Utah Parks position.

Underwood designed the new lodge for Bryce on which construction began in 1924. That building was completed by early summer, 1925. The north and southeast wings were added in 1926, and the auditorium in 1927. Most of the wood-frame standard and economy cabins he designed were completed in 1927. Five deluxe cabins had been built by that time, and ten more were completed in 1929. Rather than designing the entire complex at one time Underwood designed and re-designed it over a period of several years as visitation increased and the Utah Parks Company saw the need for expanded development. The Company had started accumulating stone and logs from nearby sites as early as 1923, even before Underwood had drawn the first plans for the development in its scramble to get visitor accommodations constructed. As the "U.P. Loop" became more popular with railroad travellers, Underwood continually pulled the Bryce development together with his architectural skill.

Underwood's design of the Lodge complex shows the strength, determination, and singularity of purpose common to brilliant architects. Despite the problems of designing the complex over time Underwood's buildings possess unifying qualities that create an outstanding sense of place. The larger scale of the lodge, the development's dominant building, is reinforced by the smaller cluster of deluxe cabins. The irregular massing and chunkiness of those buildings imitates the irregularities found in nature. The rough stonework and the large logs re-emphasize that connection to nature. The stones, quarried locally, match portions of the surrounding geology. The logs are the same size as the surrounding pines. The variety of exposed trusswork and the different angles of the roofs in the gift shop, auditorium, and dining room create spaces united in theme by the exposed trusswork but individually expressive in the forms of their architectural spaces. The rough stonework, the free use of logs particularly on the buildings' exteriors, the wave-patterned shingle roofs, the wrought-iron chandeliers, and the exposed framing and trusswork give the buildings a rustic honesty and informality characteristic of park architecture.

FOOTNOTES

1 Nicholas Scrattish, "Draft Historic Resource Study, Bryce Canyon National Park" (Denver: National Park Service, Denver Service Center, 1980 draft), pp. 32-33.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

National Park Service files, including List of Classified Structures and others, Rocky Mountain Regional Office.

Scrattish, Nicholas. "Draft Historic Resource Study, Bryce Canyon National Park." Denver: National Park Service, Denver Service Center, manuscript dated February, 1980.

Tweed, William, and Laura E. Soullière and Henry G. Law. National Park Service Rustic Architecture: 1916-1942. San Francisco: National Park Service, Western Regional Office, 1977.

Ullman, Leslie, and Sally Small. "Bryce Canyon Lodge Historic Structures Report." Denver: National Park Service, Rocky Mountain Regional Office, draft dated April, 1985.

Woodbury, Angus. "A History of Southern Utah and Its National Parks," Utah Historical Quarterly (August, 1950), pp. 194-211.

Zaitlin, Joyce. "Underwood: His Spanish Revival, Rustic, Art Deco, Railroad and Federal Architecture." Rough Draft on file at National Park Service, Rocky Mountain Regional Office, dated 1983.

BOUNDARIES

The boundary is an irregular line enclosing the main lodge building and the deluxe cabins. The boundary begins at a point 65 feet southwest of the southwest corner of cabin 539 and proceeds 175 feet in a northwesterly direction to the southeastern edge of the access road; then along the edge of the access road to the point 50 feet northwest of the northwest corner of cabin 500; then crossing the access road to a point 25 feet from the southeast wall of the lodge; then 50 feet southwest, 50 feet northwest, and 100 feet west running parallel to the lodge walls; then 250 feet north-northeast; then 175 feet east to the eastern edge of the access road and parking area; then following the edge of the parking area to its southeasternmost point; then 100 feet due east; then 225 due south; then 400 feet southwest to the starting point.

PHOTOGRAPHS

(click on the above photographs for a more detailed view)

Last Modified: Mon, Feb 26 2001 10:00:00 pm PDT

harrison/harrison14.htm

Top

Top