.gif)

MENU

The Wawona Hotel and Thomas Hill Studio

Yosemite

Bathhouse Row

Hot Springs

Old Faithful Inn

Yellowstone

LeConte Memorial Lodge

Yosemite

El Tovar

Grand Canyon

M.E.J. Colter Buildings

Grand Canyon

Grand Canyon Depot

Grand Canyon

Great Northern Railway Buildings

Glacier

Lake McDonald Lodge

Glacier

Parsons Memorial Lodge

Yosemite

Paradise Inn

Mount Rainier

Rangers' Club

Yosemite

Mesa Verde Administrative District

Mesa Verde

Bryce Canyon Lodge

Bryce Canyon

The Ahwahnee

Yosemite

Grand Canyon Power House

Grand Canyon

Longmire Buildings

Mount Rainier

Grand Canyon Lodge

Grand Canyon

Grand Canyon Park Operations Building

Grand Canyon

Norris, Madison, and Fishing Bridge Museums

Yellowstone

Yakima Park Stockade Group

Mount Rainier

Crater Lake Superintendent's Residence

Crater Lake

Bandelier C.C.C. Historic District

Bandelier

Oregon Caves Chateau

Oregon Caves

Northeast Entrance Station

Yellowstone

Region III Headquarters Building

Santa Fe, NM

Tumacacori Museum

Tumacacori

Painted Desert Inn

Petrified Forest

Aquatic Park

Golden Gate

Gateway Arch

Jefferson National Expansion

|

Architecture in the Parks

A National Historic Landmark Theme Study |

|

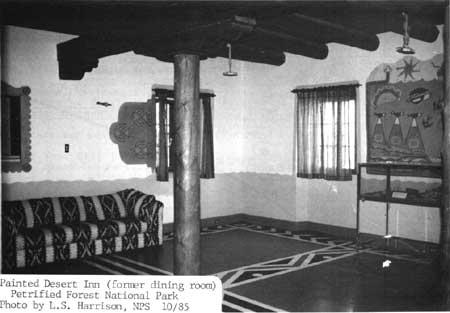

Painted Desert Inn, Petrified Forest NP, 1985.

(Photo by L.S. Harrison)

Painted Desert Inn

| Name: | Painted Desert Inn |

| Location: | Petrified Forest National Park |

| Agency: | National Park Service Western Regional Office |

| Condition: | Fair, altered, original site |

| Classification: | Building, public, accessible (restricted), temporarily closed |

| Builder/Architect: | Lyle E. Bennett (for the National Park Service) |

| Dates: | 1937-1963 |

DESCRIPTION

Painted Desert Inn is sited on a mesa top overlooking the vastness of the colorful Painted Desert. The building was constructed between 1937 and 1940 using portions of walls left over from an earlier lodge on the site that dated from the 'twenties.

From the south elevation the Inn appears to be a two-story structure arranged compactly and low to the ground. The Inn actually has an irregularly-shaped plan and is constructed on several levels as it banks into the hillside. The uppermost story is a light shaft that provides natural light for a decorative skylight in the Trading Post room. On the exterior terraces on the south, east, and north sides of the building are surrounded by low walls that define those exterior spaces. Some of the terraces overlook the Painted Desert; others articulate the entrance to the structure. Terrace flooring material is flagstone. The style of the building is Pueblo Revival, sometimes called Spanish/Pueblo style because of the Spanish Colonial elements included.

The stone walls of the building are more than two feet thick. On the exterior the walls are finished with a pink, earth-toned stucco. The multiple flat roofs are all surrounded by parapets and finished with built-up roofing. Exterior walls are pierced by canales that drain the roof and the structural viga ends, adding texture and a play between light and shadow to the walls.

The Inn contained 28 rooms that were divided into two portions: that for the National Park Service use, and that for use by the concessioner. The Park's portion included a "Ranger room" that had a public information desk, a small lobby, a drinking fountain, public restrooms, and a utility room. The government rooms had exterior entrances separate from those of the concessioner and the entire park portion of the building could be locked when not in use. The concessioner s portion included a lunch room, kitchen, dining room, dining porch, trading post room, six sleeping rooms with corner fireplaces, shower and bathroom facilities, and several utility rooms.

The ceilings in the more architecturally significant portions of the building are structural peeled log vigas with half-round or split savinos above. The vigas are supported by posts with corbels carved in Spanish-Colonial designs. Vigas, posts, and corbels are ponderosa pine. Savinos are aspen. Most of the windows in the building are paired wood-frame casements and all retain their original hardware. The stock window frames and manufactured doors and door frames were all sandblasted prior to installation to give the appearance and texture of aged wood.

The Trading Post room is a magnificent architectural space with six hammered-tin, Mexican-style chandeliers, an enormous skylight, and windows overlooking the desert for lighting. The skylight has multiple panes of translucent glass on which Indian pottery designs were painted in opaque paints. The posts supporting the corbels and vigas are painted in Spanish-Colonial designs in muted colors. Floors are random-width wood. The Ranger Room adjacent to this room contains an information desk and a small office space behind. The floor in this room is concrete scored in an Indian design.

The Kabotie room has Indian blanket designs scored into the concrete and painted in white, red oxide, and adobe colors. The room contains four murals by Hopi artist Fred Kabotie and one gouache painting that is framed and hangs in a wood built-in bookshelf. The light fixtures in this room are covered with deerskin. French doors lead out of this room to a recessed corner porch overlooking the Painted Desert. The porch has a scored concrete floor. Wooden benches with carved Spanish- Colonial designs provide seating on the porch.

The former coffee shop also has hammered-tin chandeliers. Wall- to-wall carpeting covers the original flooring material. A painted wainscot surrounds the plaster walls. Two murals by Fred Kabotie decorate the walls. All of the counters and stools for the coffee shop have been removed. The kitchen, adjacent to this room, retains its original cabinets and concrete floor; kitchen appliances and hardware have been updated since construction.

Flagstone steps lead down from the Trading Post room to the building's first floor which originally functioned as a bar. This room also has a flagstone floor laid in a pattern that repeats in 4x5-foot sections. The original bar is covered by a staging constructed to hold museum exhibits, although the bar remains intact underneath. The radiators to heat this rooms were incorporated into low walls and hidden by wooden grilles of Spanish-Colonial design.

The Painted Desert Inn opened for business in July of 1940. Inn operations were shut down during World War II but started up again in 1946. Shortly after the end of the war the Fred Harvey Company, which operated concessions for the Santa Fe Railway, took over the operation of the Inn and ran it until 1963. Since 1963 the building has been used intermittently as a museum, interpretive space, and meeting hall.

Changes to the building through the years have been relatively minor. The Fred Harvey Company removed the original windows and replaced them with large plate-glass windows in the curio shop and dining room in 1948. An electric heater was added to a viga in the Ranger Room. In recent years wrought-iron grilles were added to all doors and windows and in some places on the interior. The exterior grillework was added for security reasons since the building is subject to some vandalism. Some of the interior wrought-iron was for security, but the grillework on top of the wall surrounding the stairwell down to the bar serves no useful purpose. All of this grillework is removable. The National Park Service is in the process of removing asbestos insulation from the heating system for health and safety reasons.

STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE

Painted Desert Inn's significance arises from its masterful combination of architecture and design resulting from the fine architectural skills of National Park Service architect Lyle E. Bennett and enhanced by the artistic skills of Hopi artist Fred Kabotie. On a regional level of significance is its importance as a tangible product and symbol of the work relief programs of the New Deal.

The original building on the site dating from the 'twenties was a stone structure--even some petrified wood was used in construction--with a mud mortar. The walls had been partially tuck-pointed with portland cement to keep the mud mortar from wearing away. The building housed a trading post and lunch counter but had no water or electricity. When the National Park Service acquired the building in 1936 using funds from the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the bentonite clays on which the building was constructed were already doing damage to the stone walls. Rather than tearing down the building, park service designers chose to do a major "rebuilding" since funding for new construction was difficult to obtain and money for "rebuilding" was relatively easy to obtain. [1] Even so, the available National Park Service (NPS) funding to "rebuild" the structure was too little to cover estimates that contractors submitted to build the new Inn, so the NPS design staff used the money instead to purchase all of the materials and used labor from the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp at nearby Rainbow Forest.

The park obtained ponderosa pine logs for vigas and structural timbers from Sitgreaves National Forest and aspen for the savinos from the White Mountain Apache Reservation. Both areas disguised the wood appropriation as "forest thinning" rather than timber harvesting for construction use which probably would not have been approved. The CCC workers peeled the logs, cut the heavy corbels, and shaped the beams. The CCC foremen and onsite supervisory architect Lorimer Skidmore decided that the walls of the existing structure were structurally unsound so they had the CCC workers brace portions of walls and put new footings in where necessary and completely tear down other sections and rebuild them.

As construction on the building progressed, the supervising architect explained the building's finer points:

The architectural style of this building is influenced by the dwellings of the Pueblo Indians. A softening and decorative touch of Early Spanish is introduced by the use of adzed beams and carved corbels and brackets. Windows, doors, and frames are sandblasted. The ceilings, excepting in the utility rooms, are framed of local Ponderosa Pine "vigas" [beams] exposed in rooms across which are placed split and whole aspen savinos in Indian fashion, form [sic] the finished ceilings. The three coat lime plaster walls are finished with a lime putty finish. Floors are flagstone or concrete, except those in the Trading Post room, lunch room, and kitchen, which are of wood.. ..The building presents a very pleasing appearance from the exterior and blends harmoniously with the surroundings. It is entirely in character being located in the heart of Hopi, Navajo, and Zuni Indian country. [2]

One of the construction foremen who worked on the building commented that the subtleties of the building were among its most important features. The door and window openings, for instance, had semi-oval shapes rather than right-angled edges. He noted that: "This shape was produced in the rock and plaster to resemble the openings in old pueblo buildings where the wet adobe was shaped by the sweeping motions of the women's arms that shortened the horizontal width of the opening at the top and bottom. Consider the difficulty of teaching a journeyman mason to understand ....After much arm waving they got the message and were able to proceed." [3] That same foreman recalled how the scoring marks in concrete resembled Indian blanket designs and were stained in soft tints and how the soft tints were repeated in the carved furniture colors and wall colors. In his words: "The whole interior seemed to glow with soft, blended coloring. The time I had personally spent with Mr. Bennett was a revelation to me on what can be accomplished with color combinations" [4]

The concrete scored in Indian blanket designs, the Spanish Colonial furniture, the skylight with its prehistoric pottery designs and the subtle interior colors were all design contributions of Lyle Bennett. Bennett had received a degree in fine arts from the University of Missouri where his major field of study had been architecture. Bennett joined the park service as a ranger at Mesa Verde in 1927 where he worked in the museum and with park archeologists. He began doing architectural work for the park service in the early 1930s. He designed most of the CCC-built structures and furniture at Bandelier National Monument, a number of structures at Carlsbad Caverns, the 1930s buildings at White Sands National Monument, and additions to buildings at Mesa Verde. Although his admitted architectural preferences were along the modern lines of Frank Lloyd Wright he set those interests aside in the fine pueblo revival buildings he designed for the park service. His command of that southwestern idiom was masterful. His design for the skylight came from years of careful study of prehistoric pottery that he restored at Mesa Verde and that he read about in publications of the University of New Mexico. [5] He studied ceiling structure in pueblo-revival buildings in New Mexico. His sensitivity for colors came from his artistic training at the University of Missouri. His abilities to combine those finer elements of design with simple building materials to create impressive architectural spaces was a product of experience and talent.

In 1947 the Fred Harvey Company's own architect/designer Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter came to the Painted Desert Inn to update the building to Fred Harvey standards. She changed the interior color scheme and hired Hopi artist Fred Kabotie to paint a series of murals on the interior walls. Kabotie even at that time was a well-known Indian artist and Colter had used his talents in painting murals in some of her buildings at Grand Canyon. The Painted Desert Inn murals may be some of the last murals he ever painted, since he switched to working in silver shortly afterwards. The paintings on the walls of the former dining room and coffee shop depict aspects of Hopi every-day life and ceremonial or religious symbolism. One mural shows the importance of the eagle to Hopi life. Another tells the story of the young men's trip to Zuni salt lake to collect salt and a third illustrates the Buffalo Dance. In discussing the salt lake mural Kabotie said: "I was commissioned by the Fred Harvey Company to do the mural paintings here at the Painted Desert Inn. I had been thinking over what subject I should do, when it occurred to me that the Hopi people...used to travel right through this country to go after their salt...." [6] Smaller murals show two birds, and two Hopis grinding corn. The dining room was formally dedicated as the Kabotie room on June 23, 1976. Kabotie passed away recently.

The Painted Desert Inn remains an important piece of southwestern pueblo revival architecture. Its construction techniques were sound considering the unstable clays on which the building was constructed, but they were not particularly noteworthy. The building's importance lies in its artistic design which permeated the exterior but was brought to its highest level on the interior.

FOOTNOTES

1 Lyle E. Bennett to Laura Soullière Harrison, undated letter received October, 1985.

2 Lorimer Skidmore, " Report to the Chief of Planning on Construction of the Painted Desert Inn at Petrified Forest National Monument, Holbrook, Arizona" (San Francisco: National Park Service Branch of Plans and Design), pp. 4-5.

3 Harold W. Coleman to David Ames and Hoyt Rath, February, 1976, p. 8.

5 Interview with Lyle E. Bennett conducted by Laura Soullière Harrison, March 10, 1985.

6 Two-page narrative entitled "The Zuni Salt Lake Trip Mural: Kabotie Room, Painted Desert Inn," available at Petrified Forest National Park.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cole, Harold W. "Construction History, Painted Desert Inn, Petrified Forest National Park," June, 1976, manuscript on file at Petrified Forest National Park.

Cole, Harold W. to David Ames and Hoyt Rath, February, 1976. Letter in the collection at Petrified Forest National Park.

Cornell, Harvey, "Monthly Narrative Report to Chief Architect," November, 1937.

Interview with Lyle E. Bennett, conducted by Laura Soullière Harrison, March 5, 1985. Transcripts on file at the Western Regional Office and Petrified Forest National Park.

Kuehl, Al, Associate Landscape Architect, Branch of Plans and Design, "Monthly Narrative Report to the Chief Architect," August 20-September 20, 1937.

National Park Service files including List of Classified Structures and National Register files.

National Park Service Historic Preservation Team, Western Region, Evaluation of Structures and Historic Resources, Petrified Forest National Park. 1975. Report on file at the National Park Service, Western Regional Office.

Skidmore, Lorimer, Supervising Architect, Report to the Chief of Planning on Construction of the Painted Desert Inn at Petrified Forest National Monument, Holbrook, Arizona, P.W.A. project no. 669, C.C.C. job no. 350. San Francsico: National Park Service, no date but probably October 1, 1938.

"The Zuni Salt Lake Trip Mural: Kabotie Room, Painted Desert Inn," pamphlet on file at Petrified Forest National Park.

BOUNDARIES

The boundary is shown as the dotted line on the enclosed sketch map (omitted from on-line edition). The boundary line begins at a point on the north edge of parking lot 200 feet southeast of the southeast corner of the building, then proceeds 200 feet northeast to the 5820 feet contour line, then following that contour line (geologic rim) around to a point 150 feet west of the northwestern corner of the Inn, then 100 feet due south to the north parking lot edge, then following the curb of the parking lot back to the starting point.

PHOTOGRAPHS

Painted Desert Inn (former dining room), Petrified Forest NP, 1985.

(Photo by L.S. Harrison)

Last Modified: Mon, Feb 26 2001 10:00:00 pm PDT

harrison/harrison28.htm

Top

Top