.gif)

MENU

The Wawona Hotel and Thomas Hill Studio

Yosemite

Bathhouse Row

Hot Springs

Old Faithful Inn

Yellowstone

LeConte Memorial Lodge

Yosemite

El Tovar

Grand Canyon

M.E.J. Colter Buildings

Grand Canyon

Grand Canyon Depot

Grand Canyon

Great Northern Railway Buildings

Glacier

Lake McDonald Lodge

Glacier

Parsons Memorial Lodge

Yosemite

Paradise Inn

Mount Rainier

Rangers' Club

Yosemite

Mesa Verde Administrative District

Mesa Verde

Bryce Canyon Lodge

Bryce Canyon

The Ahwahnee

Yosemite

Grand Canyon Power House

Grand Canyon

Longmire Buildings

Mount Rainier

Grand Canyon Lodge

Grand Canyon

Grand Canyon Park Operations Building

Grand Canyon

Norris, Madison, and Fishing Bridge Museums

Yellowstone

Yakima Park Stockade Group

Mount Rainier

Crater Lake Superintendent's Residence

Crater Lake

Bandelier C.C.C. Historic District

Bandelier

Oregon Caves Chateau

Oregon Caves

Northeast Entrance Station

Yellowstone

Region III Headquarters Building

Santa Fe, NM

Tumacacori Museum

Tumacacori

Painted Desert Inn

Petrified Forest

Aquatic Park

Golden Gate

Gateway Arch

Jefferson National Expansion

|

Architecture in the Parks

A National Historic Landmark Theme Study |

|

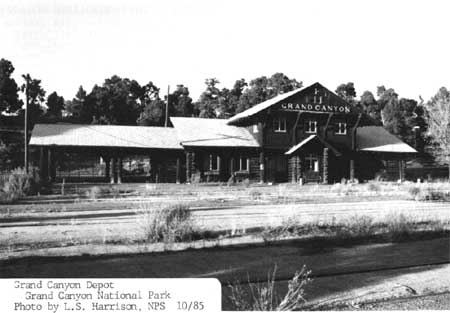

Grand Canyon Depot, Grand Canyon NP, 1985.

(Photo by L.S. Harrison)

Grand Canyon Depot

| Name: | Grand Canyon Depot |

| Location: | Grand Canyon National Park |

| Agency: | National Park Service Western Regional Office |

| Condition: | Fair, original site |

| Classification: | Building, public, unoccupied, accessible (restricted), storage |

| Builder/Architect: | Francis Wilson (for the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway) |

| Dates: | 1909-present |

DESCRIPTION

The Grand Canyon Depot is a log and wood-frame structure with a central section two-and-a-half stories in height and wings to the east and west each one-and-a-half stories. The building's foundation is concrete. The gable roof of the two-story section rums on a north-south axis, and those of the wings on an east-west axis. The intersecting gable roofs are finished with green-painted asbestos shingles. The south gable end frames the Santa Fe logo near the ridge, with the identifying "Grand Canyon" name below in green copper letters. Centered below that on the first floor is a log bay projecting out from the building's mass, sheltered by a small gable roof. Another Santa Fe logo is centered in this gable end. The baggage loading platform and baggage room are at the east end of the building. The waiting platform and ticket booth are at the west end. The front elevation faces south and overlooks the remaining tracks.

The design details of the log construction are unusual. The logs are squared on three sides creating bearing surfaces and flat interior surfaces. The bottom sides of each log are routed to hold wood strips wrapped in building paper which drapes between the logs and over the faces of the lower logs. The squared logs are drawn tightly together at the corners and again lined with building paper. These techniques have limited the amount of moisture penetration throughout the years, leaving the logs in good structural condition. The false crowns of the logs are axe-cut, giving the building a frontier/western feeling. Building corners in the main two-story portion are finished with peeled log posts. All of the walls of the buildings are logs, with the exceptions of the log-slab addition at the west end waiting platform, and the upper story whose walls are finished with wood shingles double-coursed every second row. The second story overhangs the first by more than one foot. Log brackets on the upper story support the roof whose gable ends project out two feet from the second story. The shadows created by the long eaves and overhangs reinforce the building's horizontal emphasis. The building logs and shingles are stained dark brown. Most of the windows in the building are paired wood-frame casements with six-light fixed transoms above. Paired log posts support the roof over the passenger-loading area. The log framing of the roof structure above it is exposed.

The first floor of the building contains the former waiting room, ticket office, restrooms, baggage room, and various other public and work spaces. The floor is scored concrete. The log-slab wainscotting and molding around the doors and windows contributes to the building's rustic quality. Above the wainscoting is off-white plaster. The dark stain of the wainscoting and moldings is similar in color to the log slab panelling on the interior of El Tovar. An interior staircase leads from the first floor up to the apartment formerly occupied by the station agent. The apartment contains living room, kitchen, pantry, bath, two bedrooms, and storage and utility areas. The floors in the apartment are wood, with linoleum finishes in the kitchen, pantry, and bath. The walls are plaster.

The building contains a considerable amount of its original hardware bearing the stylized letters "GC" for Grand Canyon, although some of this hardware has been stolen in its years of abandonment. All original doors remain and are either solid planks with wrought-iron bolts and hardware, or glazed or solid with multiple wood inset panels.

An iron fence at the east and west ends of the building, with a gate for access to the baggage loading dock at the east end, is extant but is in damaged condition. The collapsible metal fencing closing off the track side of the outdoor passenger waiting area from the tracks is in better condition. What remains of the track, platforms and passenger yard are an essential part of the historic scene of the Grand Canyon depot, for the depot could not have functioned without them.

A mew Victorian-style depot was designed by a railway employee in 1907, but it was not built. That design, however, did serve as the basic floor plan for the larger 1909 design done by Santa Barbara architect Francis Wilson. Wilson's log depot was constructed in 1909-1910. The original copper letters on the front elevation spelling out "Grand Canon" were changed to "Grand Canyon" by 1911. Probably in 1925, the size of the women's restroom was reduced to create additional office space. A storm vestibule and small ticket office of log-slab siding were added to the west end of the building under the covered passenger platform in 1929. That same year, the iron fence was built at the east and west edges of the depot to enclose the railroad yard. The agent's office inside the depot was remodelled in 1939, but the nature and extent of this work in not known. Asbestos shingles, replacing the original wood shingles, were installed on the roofs in 1940. The original pole lookouts at the gable ends reminiscent of those at Old Faithful Inn at Yellowstone were probably removed at the same time. Some foundation work was done in 1948 to discourage termites. Copper steam pipes were also installed, and the baggage loading platform at the east end of the depot was rebuilt, also in 1948. The floor plan was revised in 1949 to show changes in the women's restroom. It is unclear whether these plans reflected existing conditions from the 1925 change or perhaps served as the documents for interior changes made in 1949. Fluorescent lights to augment existing lights were added in 1954 at the same time that additional interior changes of an uspecified mature were completed. The last passenger train used the depot in 1968, and the freight office closed a year later. The building has been used intermittently since that time but is mow vacant.

STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE

The Grand Canyon Depot has multiple aspects of significance. First, the building is one of approximately 14 log depots known to have been constructed in the United States, and it is one of three remaining. Out of those three, the Grand Canyon depot is the only one where logs were used as the primary structural material, rather than as ornament to make the building seem more rustic [1]. As an architectural symbol, the building served as the introduction to the Grand Canyon setting the tone for the visitor experience during days of train travel; and it continues to contribute a substantial sense of place to the area so painstakingly developed as a "destination resort" by the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway. The depot is integrally connected with the development of El Tovar and the South Rim of the Grand Canyon and as such had a major impact on revenues of the Santa Fe system and on the nation's entire railway network through connecting service with other railroads. The depot is at the branch-line terminus of the only railroad line inside national park boundaries--the railroad came first and then the park was created. The massive publicity campaign undertaken by the Santa Fe increased public awareness of the Grand Canyon and undoubtedly aided in efforts to establish the area as a national park in 1919.

The first railroad into the Grand Canyon vicinity was the Santa Fe and Grand Canyon Railroad, organized in 1897. The company went bankrupt in 1900, when its tracks were still eight miles short of their South Rim destination. The Grand Canyon Railway, organized by a subsidiary of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway, bought out the bankrupt short line and finished construction of the rails in 1901. The Railway developed the railroad yard and the luxurious El Tovar hotel and built a small frame depot to accommodate passengers coming and going. The boom in railroad tourism, brought about by railroad promotions of destination resorts like the South Rim, created the need for a larger depot that would contribute to the image the railway was seeking. The economic push behind the idea of a destination resort was not that the railway made money off accommodations when visitors came to an area and vacationed there for several weeks; their biggest revenues came from increased passenger traffic.

The use of the Grand Canyon--as a main resort and the key feature depicted in advertising and timetables--was so successful that the "Grand Canyon Line" which originally referred only to the branch line between Williams, Arizona, and the Grand Canyon, became synonymous with the entire Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway system.

To visitors the depot still represents the concept of a western national park: rustic and scenic. When train travel was the primary mode of getting to Grand Canyon even before the area was set aside as a park, the depot was the gateway through which they entered the developed area of the South Rim. The building's style and ambience was perfect for the feeling of civilized frontier that the Railway created in their south rim development. The depot, with the "Grand Canyon" name prominently displayed on its front elevation, remains an architectural focal point continuing to draw attention to that rustic image. Today visitors are consistently causing traffic jams when they stop on the road to photograph that symbol of a national park. The building is the most photographed structure at Grand Canyon.

The architect of the depot was Francis Wilson, who designed a number of residences and community buildings around Santa Barbara, including a residence for Edward Payson Ripley, president of the Santa Fe Railway. Wilson's training had been as a draftsman working with Albert Pissis, designer of major neo-classical revival buildings in San Francisco, and through the study of European architecture during his extensive travels there. His first job with the railroads was designing the Santa Barbara passenger depot for the Southern Pacific. He then moved on to employment with the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway--undoubtedly based on his previous work for Ripley--designing depots and depot hotels at Ash Fork and Williams, Arizona, and Needles and Barstow, California. He was involved with the remodelling of Bright Angel Hotel at Grand Canyon, and then began work on the Grand Canyon depot in 1909. Most of Wilson's designs were typically Californian in nature: buildings with mission-revival and mediterranean influences with a hint of an arts-and-crafts character--typical of what other California architects of the time were doing. His log depot at Grand Canyon, however, was unique in his work as the only log building and the only rustic building he designed. Yet even this building had some classical undercurrents, with its symmetrical configuration and rustic pediments.

Francis Wilson designed the building with obvious connections to El Tovar. The logs were compatible with the log slab siding of the large hotel. The chandelier in the waiting room was similar to those in El Tovar. The dark wood wainscotting was the same deep brown as the interior panelling at El Tovar. Even the local newspaper commented in 1909 that the railway was in the process of building a "rustic bungalow station at Grand Canyon, patterned after the El Tovar Hotel." The rustic feeling inspired by this building was subordinate to, yet complimented the finer appointments of El Tovar. Wilson's choice of details in construction--fitting the logs together so tightly that water could not penetrate, and allowing for good drainage whenever possible--were far superior to the log construction details of El Tovar.

Passenger service to Grand Canyon ended in 1968. A railroad agent remained at the depot to handle freight, but that operation was shut down a year later. The National Park Service acquired the property in 1982 in a series of legal proceedings involving other Santa Fe properties and rights-of-way at the Grand Canyon. Since the depot's closing as a railway office, the building has been used as construction offices, as a small interpretive center, and as a concession for renting hiking and backpacking equipment. In recent years a private firm has shown interest in reviving the train ride from Williams to the Canyon, and putting the depot back to its original use. Funding problems have slowed their progress. The depot's present lack of functional integrity may yet be restored.

FOOTNOTES

1. Gordon Chappell, "Statements on Architectural and Historical Significance," ins., 1985, available in the National Park Service's Western Regional Office, no pagination.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Borjes, Ric, and Gordon Chappell. The Grand Canyon Depot and Railroad Yard: 1901-1984. Historic Structures Report. San Francisco: National Park Service, 1984.

Chappell, Gordon. "Statements on Architectural and Historical Significance," Ms. material. 1985.

Cleek, P.G. "Francis W. Wilson, Architect," Noticias (Journal of the Santa Barbara Historical Society), Vol. XXXI. No. 3, Fall 1985.

BOUNDARIES

The boundary for this property is the same as listed on the National Register form. The eastern edge is bounded by the bridge connecting the North and South Loop Roads; the southern boundary is the north edge of South Village Loop Road; the north boundary is the south edge of North Village Loop Road; the west boundary is a north-south line 200 feet west of the western edge of the waiting platform connecting the north and south boundaries.

PHOTOGRAPHS

(click on the above photographs for a more detailed view)

Last Modified: Mon, Feb 26 2001 10:00:00 pm PDT

harrison/harrison7.htm

Top

Top