.gif)

MENU

The Wawona Hotel and Thomas Hill Studio

Yosemite

Bathhouse Row

Hot Springs

Old Faithful Inn

Yellowstone

LeConte Memorial Lodge

Yosemite

El Tovar

Grand Canyon

M.E.J. Colter Buildings

Grand Canyon

Grand Canyon Depot

Grand Canyon

Great Northern Railway Buildings

Glacier

Lake McDonald Lodge

Glacier

Parsons Memorial Lodge

Yosemite

Paradise Inn

Mount Rainier

Rangers' Club

Yosemite

Mesa Verde Administrative District

Mesa Verde

Bryce Canyon Lodge

Bryce Canyon

The Ahwahnee

Yosemite

Grand Canyon Power House

Grand Canyon

Longmire Buildings

Mount Rainier

Grand Canyon Lodge

Grand Canyon

Grand Canyon Park Operations Building

Grand Canyon

Norris, Madison, and Fishing Bridge Museums

Yellowstone

Yakima Park Stockade Group

Mount Rainier

Crater Lake Superintendent's Residence

Crater Lake

Bandelier C.C.C. Historic District

Bandelier

Oregon Caves Chateau

Oregon Caves

Northeast Entrance Station

Yellowstone

Region III Headquarters Building

Santa Fe, NM

Tumacacori Museum

Tumacacori

Painted Desert Inn

Petrified Forest

Aquatic Park

Golden Gate

Gateway Arch

Jefferson National Expansion

|

Architecture in the Parks

A National Historic Landmark Theme Study |

|

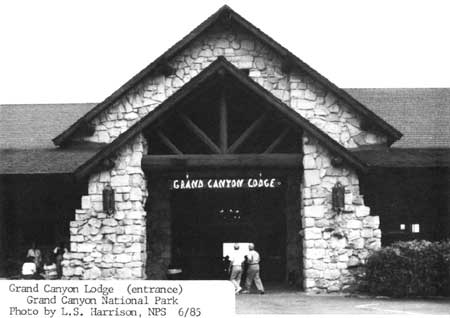

Grand Canyon Lodge (entrance), Grand Canyon NP, 1985.

(Photo by L.S. Harrison)

Grand Canyon Lodge

| Name: | Grand Canyon Lodge |

| Location: | Grand Canyon National Park |

| Agency: | National Park Service Western Regional Office |

| Condition: | Good, altered, original site |

| Classification: | District, public, accessible (unrestricted/restricted), commercial/government |

| Builder/Architect: | Utah Parks Company and Gilbert Stanley Underwood |

| Dates: | 1927, 1936-present |

DESCRIPTION

Grand Canyon Lodge is a complex consisting of a main lodge building, 23 deluxe cabins, and 91 standard cabins on Bright Angel Point, a promontory on the north rim of the Grand Canyon. The lodge is banked into the side of the rim and is the central feature. The deluxe cabins are clustered to the northeast of the main lodge, and the standard cabins to the southwest. The deluxe cabins are on a slight rise while the standard cabins are placed on a gentle slope leading down into Transept Canyon.

When constructed in 1927-28, Grand Canyon Lodge consisted of the main lodge building, 100 standard cabins, and 20 deluxe cabins for guest accommodations. The main lodge and two deluxe cabins burned in 1932. The deluxe cabins were not rebuilt, but the main lodge was rebuilt in 1936-37 using most of what remained of the stone foundation, piers, walls, and chimneys of the original building. The rebuilt main building retained the general configuration of the first lodge with a few exceptions. The observation tower in the center of the structure and the second-story log dormitory were not rebuilt. The new rooflines were considerably steeper in pitch than the original--a change probably made to allow the building to shed the heavy winter snows more readily. This change also re-directed the architectural intent of the main lodge building. Rather than a rustic building with strong Californian overtones of the craftsman and Spanish revival styles, the new structure was less stylized and became strictly rustic--dependent more on its stone and logs for stylistic definition than its low rooflines and massing.

The main lodge is U-shaped in plan and is constructed of Kaibab limestone, ponderosa logs, and log-slab siding on wood frame construction. The multiple roofs primarily are intersecting gables with broken pitches that are further broken up by shed and gable dormers. All of the roofs are finished with wood shingles. Log outlookers project beyond the rooflines from the gable ends. The stonework is random rubble masonry bonded with cement mortar. Portions of wall between the stone piers and the stone wall sections are filled with dark-stained log siding with cement chinking, and large expanses of plate glass particularly on the south elevation facing the canyon.

The main lodge building contains the registration lobby, dining room, recreation room, "western saloon," sun room, "buffeteria," kitchens, and various offices and utility rooms. The enclosed portion of the "U" at the north contains a variety of porticos and surrounds the entrance loop road and small planted island at the north end of the building. The principal entrance to the saloon is on the eastern portion of the "U" and the entrance to the buffeteria is on the western portion. The south-facing elevation overlooks the canyon and has open terraces on separate levels to the east and west with an enclosed sunroom between them. Directly below the sunroom is an additional observation deck with smaller openings overlooking the canyon. The eastern terrace has edges defined by stone walls and is particularly noteworthy for its hugely overscaled fireplace--large enough for average humans to walk into without ducking--and the enormous stone steps leading back up into the building.

The main entrance at the internal center of the "U" is marked by large double gables that project in a dormer fashion out of the main roof. Stepped stone piers support the outside gable, and each holds an enormous wrought-iron lamp. The decorative logwork between the piers is a king-post truss with additional log knee-braces. On the interior the spaces are divided up several levels that naturally step down the canyon rim. The recreation room is a few steps above the lobby. The dining room is a few steps below the lobby level as is the sunroom. Exposed roof trusses that are actually steel covered by logs highlight the major public spaces--the lobby, the recreation room, and the dining room. Most interior walls are stone but some are vertical and/or horizontal logs with a dark stain that contrasts with the light cement chinking. Throughout the building the huge wrought-iron chandeliers and sconces, and the painted and carved Indian symbols add visual interest and contribute to the building's sense of style. The building has changed very little since 1937. Some interior partitions have been added or modified and the terraces were finished with concrete; all other changes have been of a cosmetic nature.

The deluxe cabins to the northeast of the main lodge are structures made of half-log siding on wood frames with stone corner piers and stone foundations. The log siding runs horizontal on the main walls and vertical in the gable ends. The siding is chinked with cement mortar. Chimneys of highly textured limestone are laid in rough courses. The chimneys, exposed on exterior walls and incorporated into corner piers, pierce the gable roofs at the ridges. The roofs are finished with wood shingles. The cabins are both duplexes (18 total) and quadruplexes (5 total), and are rectangular and square in plan respectively. All of the units have handsome peeled log entrance porches on stone foundations. The double-hung windows in the cabins are frequently paired and are surrounded by log-slab moldings. The interiors contain stone fireplaces, and exposed log ridgepoles and rafters. Bathrooms are updated. Twenty duplex cabins were constructed in 1928, but two burned during the 1932 fire and were not replaced. The five quadruplexes were built by 1932.

North of the deluxe cabins is a small linen storage building of wood-frame construction with half-log siding. This building is also included in this nomination.

The 91 standard cabins are smaller than the deluxe cabins and are placed much more closely together. These are of true log construction rather than log siding on frame construction. The buildings are divided on the interiors by log partitions separating the two units of each cabin. The cabins are rectangular in plan, and 46 of them have small additions sheathed with log-slab siding to house bathrooms. The gable roofs are finished with wood shingles. Rather than the elaborate entrance porches on the deluxe cabins, these building have simple steps leading up to the entrance doors. Some of the cabins have been changed to other uses such as linen storage, a first-aid station, a dispensary, and employee quarters. Some of the original standard cabins were moved to the north rim campground in 1940.

Grand Canyon Lodge has a strong pioneer flavor that remains today despite the crowds and vehicles. The log and stone building materials, the very human scale of the cabins, the topographic scattering of the development, crowned by the main lodge building and its grand vistas, make the Lodge the rustic visitor experience that the Union Pacific Railroad intended it to be.

STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE

Grand Canyon Lodge is the most intact rustic hotel development remaining in the national parks from the era when railroads fostered construction of "destination resorts." Constructed of native stone and timber the complex was designed to harmonize with its rocky and forested setting on the north rim of the Canyon and designed to create a particular sense of place that made the lodge a unique and noteworthy destination at the Grand Canyon. On a regional level of significance the complex is significant in the categories of transportation and tourism as part of the group of resorts constructed by the Union Pacific Railroad in Utah and northern Arizona.

During the 1920s the Union Pacific Railroad constructed a spur from their main line in Lund, Utah, south to Cedar City. After careful study of the competition, the Railroad directors saw a potential for moving freight--namely foodstuffs and ore--out of Cedar City and increasing passenger traffic on their main line by providing ground transportation to resorts they would build at Zion, Cedar Breaks, Bryce, and the north rim of the Grand Canyon. Passenger traffic on main lines--where railroads made considerable money--increased dramatically when the railroads provided resorts like the backcountry chalets of Glacier or El Tovar on the south rim. The Union Pacific was not about to fall behind the Santa Fe, the Canadian Pacific, or the Great Northern. They needed to create an image and sense of place for their resorts, as the other railroads had. The natural wonders of the national parks drew more visitors when the scenic beauty was enhanced by significant architecture worthy of writing home about.

The director of the newly-formed National Park Service saw limited resort development to park service advantage, too. Appropriations for running the parks were based on visitation, and overnight lodging was necessary to increase those numbers. At the same time the park service took a strong hand in encouraging an architecture suitable to the scenic wonders of the national parks. From the beginning the park service had review authority over concessions development. Additionally the early emphasis on the employment of landscape architects and concurrent evolution of an architecture in harmony with its environment had strong impacts on the types of buildings constructed in the parks. Through years of experiments in architecture certain standards were emerging. These included the use of natural materials and detailing that made the buildings look as if they had been constructed by craftsmen with primitive hand tools, and the careful selection of, in this instance, the stones and logs of the proper scale so that their size and configuration were parallel to rock outcroppings and surrounding forest.

One of the shapers of these standards of what became known as rustic architecture was Gilbert Stanley Underwood. Underwood came to the Union Pacific with a strong working background and degrees from both Yale and Harvard. Underwood began his career as an apprentice in Los Angeles to several important California architects who worked in styles from Beaux-Arts classicism to Mission Revival. After twelve years working as an apprentice he returned to school and finally earned his degrees, and then he returned to Los Angeles and set up an architectural office. Some of his early designs were for the core park service development in Yosemite Valley. Although his designs were rejected for a variety of reasons, Stephen Mather, Horace Albright, and members of the early "landscape" staff such as Underwood's friend Daniel Hull, were impressed with his work and may have recommended him for the Utah Parks Company position. Underwood's designs for the Zion, Bryce, and Grand Canyon Lodges, and later the Ahwahnee at Yosemite and Timberline Lodge on Mount Hood earned him a reputation as an architect more than successful in his use of natural materials to create buildings that fit with their settings and possessed a spatial excitement unique to his work.

The most important features of the Grand Canyon Lodge complex were based on Underwood's decisions. The way the stonework of the foundation, walls, and piers banked into the rim and in some places even looked like rock outcroppings was a product of Underwood's skill in design. The variety of terraces looking out over the rim were, for the most part, his decisions. Underwood was a master of the spatial experience on a grand scale and used the resource--in this case the canyon rim and the vistas from it--to greatest advantage in his design. In siting the standard cabins amidst the hilly topography and pine forest, he let the site dictate placement of the cabins at gentle angles with meandering pathways connecting them. By avoiding straight lines in their placement he created a comfortable, rustic atmosphere that gave visitors of more modest means the woodsy frontier feeling they sought on their western vacations and which the railroad and its architect provided so well. The deluxe cabins had larger spaces between the buildings giving a more open atmosphere. The stones and logs used in the construction and the larger size of the buildings gave more affluent visitors what they paid for--luxurious comfort in the wilderness and the exotic feel of their own frontier cabin, with the added dash of status provided by the more impressive architecture.

Whether Underwood was involved or not in the rebuilding of the Lodge after the 1932 fire remains in question. [1] In any case the rebuilt main structure, while not as architecturally spectacular as the original, retains its status as key building of the district and considerable "Underwood flavor." The significance of the district does not hinge on Underwood's involvement, however. Other rustic accommodations on this grand a scale and with originally comparable architecture have been altered considerably. On the south rim Bright Angel Lodge has undergone considerable alteration, as has Phantom Ranch in the Canyon. In the resorts built by the Union Pacific, Zion has lost its original lodge and Bryce Canyon Lodge has lost all of its budget cabins and soon will all but a handful of its standard cabins. At Glacier a number of the original chalets no longer exist. Yosemite Lodge, not near the original architectural quality as these others, has also been altered substantially. Grand Canyon Lodge as a complex, then, is the only complete development of railroad-built rustic architecture left intact.

FOOTNOTES

1 None of the architectural drawings for the rebuilding of the main lodge structure have his signature. At the time the drawings were completed--1936, Underwood was no longer working for the Union Pacific/Utah Parks, but was a federal employee. As consulting architect to the Treasury Underwood was not supposed to work on outside projects, but he did moonlight some architectural work. The rebuilding of the main lodge structure is not known to be part of that body of work. For further information see Zaitlin's manuscript "Underwood: His Spanish Revival, Rustic, Art Deco, Railroad and Federal Architecture."

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Garrett, Bill. Grand Canyon Lodge Historic Structure Report. Grand Canyon National Park, 1984.

National Park Service, Western Regional Office files including National Register and List of Classified Structures files.

Tweed, William C., Laura E. Soullière, and Henry G. Law. National Park Service Rustic Architecture: 1916-1942. San Francisco: National Park Service, Western Regional Office, 1977.

Zaitlin, Joyce. "Underwood: His Spanish Revival, Rustic, Art Deco, Railroad and Federal Architecture." Manuscript dated 1983 on file at National Park Service, Rocky Mountain Regional Office.

BOUNDARIES

The boundary, as shown on the enclosed park planning map, begins at a point on the 8,200' contour line 50' southwest of the southwest corner of cabin 309; then proceeds east in a straight line to a point 100' southeast of the eastern corner of cabin 309; then north-northeast 200'; then north 150'; then northwest 250' to the parking lot edge; then following the edge up to the eastern side of the entrance road; then along the entrance road to a point 150' east of the eastern edge of cabin 154; then 200' northwest to a point 50' north of the northwest corner of cabin 156; then 230' southwest to a point 25' west of the western corner of cabin 135; then south 500' to a point 25' west of the western corner of cabin 23, then following the 8,200' contour line around the canyon rim to the starting point.

PHOTOGRAPHS

(click on the above photographs for a more detailed view)

Last Modified: Mon, Feb 26 2001 10:00:00 pm PDT

harrison/harrison18.htm

Top

Top