|

Minidoka National Historic Site Idaho-Washington |

|

NPS photo | |

I want to forget the day we were herded like cattle into a prison camp. What did we do wrong? What was our crime?

—Sylvia Kobayashi

FREEDOM DENIED

STUNNED FRIGHTENED UNCERTAIN

February 19, 1942 President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, depriving over 110,000 people of their freedom. All were of Japanese ancestry (known as Nikkei). Two-thirds were American citizens, half were children. They closed their businesses, shut down their farms, and packed their suitcases. They boarded trains and buses first to detention centers and later to prisons. For the rest of World War II, most would remain behind barbed wire.

Over 13,000 people were imprisoned in Idaho at Minidoka War Relocation Center, known locally as Hunt Camp. Now a national historic site, Minidoka traces the history of Japanese Americans from immigration in the 1800s to the commemorations of today. The park's stories link with other stories of American injustice, racial prejudice, resilience and recovery—and explores how to ensure this never happens again.

DECADES OF PREJUDICE (1880-1942)

FEAR HOSTILITY PROPAGANDA EXCLUSION

Before 1941 During the 1800s, Japanese began immigrating to the West Coast of the United States seeking work and a better life. Mostly men, they did work others did not want, such as stoop labor in fields and hauling rocks in mines. Over time, many started businesses and families. But some Americans were suspicious of these immigrants who looked different and were of a different culture. Leaders passed and enforced laws preventing Japanese immigrants from becoming citizens or owning land. Children born here would have these rights, but not their parents.

December 7, 1941 Imperial Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Fears of a West Coast invasion increased. Former incarceree Louise Kashino said, "They were the enemy to us, just like everybody else felt." Newspapers published rumors such as Japanese residents were signaling enemy ships from shore. The FBI found no truth to the rumors, but President Roosevelt listened to military advisors who insisted Nikkei were a true threat. He signed Executive Order (EO) 9066, which allowed the military to force people out of exclusion zones. Some Germans and Italians had to leave, but only Japanese endured mass removal from their homes.

March 30, 1942 Near Seattle, Washington, over 200 Nikkei living on Bainbridge Island said tearful goodbyes to their friends. They were the first people forced from their homes under EO 9066. (Japanese on Terminal Island, California, were forced out before EO 9066 was issued.) The Bainbridge Islanders were first sent to Manzanar War Relocation Center in California, but most moved to Minidoka in February 1943. They joined over 7,000 people from Seattle, 2,300 from Oregon, and 200 from Alaska.

I never swore any allegiance to Japan, I've always been an American and pledged allegiance to our flag all my life.

—Gene Akutsu

BEHIND THE FENCE (1942-44)

SUFFERING ANGER RESILIENCE

Transition Joan Morishima Seko's family was sent to a detention center hastily arranged at a fairgrounds. She recalls "staying in a stall with my parents [that] had housed horses before." They lived there for several months while Minidoka was built. After arriving at the camp, Sylvia Kobayashi says, "I can't forget the feeling of total rejection, the feeling of not belonging, the feeling of complete emptiness."

Adjustment Minidoka was not finished when Nikkei arrived in August 1942. Some incarcerees helped complete the barracks, mess halls, and other buildings. The sewage treatment plant was not completed; everyone had to use open pit toilets until February 1943. Camp conditions gradually improved but it was still a prison.

Conflict Minidoka earned a reputation for being a quiet camp, even during the "loyalty crisis" of early 1943. As a first step toward allowing incarcerees out of the camps, the US Government sent a "loyalty questionnaire" asking incarcerees to pledge their loyalty to the United States. Most Nikkei were deeply offended. Why were they still being questioned about their loyalty? Had they not shown their love for America by accepting imprisonment, unjust as it was?

Minidoka administrators tried to calm fears and frustrations by explaining that answering "yes" could help them leave the camp early or—for young men—enlist in the army. Those who answered "no" or refused to answer risked being sent to the heavily guarded Tule Lake War Segregation Center in northeastern California. Other disruptions would occur later at Minidoka, but it remained calmer than other centers.

Dad never talked about it, none of it. I never heard him say the word "Minidoka."

—Larry Matsuda

DECADES OF SILENCE (1945-70)

CHANGE DENIAL CHALLENGE

Closing Minidoka closed October 28, 1945. Nono Mitsuoka remembers mixed feelings: "Now that we were free to go as our spirit willed, we found that once again we had to face the breakup of a community which had become sort of home." Some people could return to their prewar lives. Some were welcomed into different communities. Others found their homes and businesses gone and few people willing to help. They rebuilt their lives, their livelihoods and their communities through tenacity and hard work.

Suppressing Frank Yoshikazu Kitamoto was called "Kazu" as a youngster, but his parents called him "Frank" after the war. He says they "wanted me to be as 'American' as I could be." Kitamoto also explains that most Nikkei wanted to forget the camps. They "didn't want to bring back painful memories and were concerned about what other people would think . . . They had struggled to recover from the incarceration experience and reestablished their business, etc. and were afraid of a public backlash."

Questioning Nikkei who were young children in the 1940s grew into adults during the nation's turbulent civil rights era. They saw similarities between the African American experience and their own. When Roger Shimomura. who was a youngster at Minidoka, asked to interview his father for a high-school project, his father replied "We don't talk about that in this house so don't bring it up again." But over time the incarcerees began to tell their stories.

HOPE, AWARENESS, ACTION (1970-today)

JUSTICE FREEDOM REMEMBRANCE

Some Nikkei had been working since the war to right the wrongs committed against them, and they finally saw progress. In 1976, President Gerald Ford formally terminated EO 9066. He said, "We have learned from the tragedy of that long-ago experience forever to treasure liberty and justice for each individual American, and resolve that this kind of action shall never again be repeated." A congressional commission released a report in 1983 that stated: "The broad historical causes which shaped these decisions were race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of government leadership." This report was quoted again in the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which provided a presidential apology and reparation payments to 82,000 former incarcerees.

Today most of the former camps have a reunion or pilgrimage honoring the sacrifices of Japanese American incarcerees. Japanese Americans around the country also commemorate February 19—the day that FDR signed EO 9066—as a "national dav of remembrance."

Over 70 years ago. more than 110,000 people were imprisoned by the United States because they looked like the enemy. They broke their silence so that all could learn from their experience. They continue to speak out because they know that this could happen again. They say nidoto nai yoni—Let it not happen again.

It is unendurably hot and dusty, though eventually I'll get used to it.

—Hanaye Matsushita

LIFE IN HUNT CAMP

Yoshi Uchiyama Tani remembers "the sense of community that developed as we tried to make the most of our situation." Incarcerees organized churches, recreational activities, and a consumer cooperative. They also planted gardens to bring beauty and familiar food back into their lives.

Children were busy making new friends. Hisa Matsudaira, who had come from a farm far from other kids, says, "So you step out the door here and here they all are. I played a lot.... We played marbles, jacks, jump-rope ... all kinds of things."

Incarcerees helped camp neighbors too. The Amalgamated Sugar Company wrote, "Thousands of volunteer victory workers from Hunt have helped to thin, cultivate and harvest sugar beets . . . thus precious crops have been saved." In August 1943, Minidoka firefighters helped subdue a wildfire 60 miles from camp. Such efforts helped many Idaho residents better understand these people imprisoned by prejudice.

WALKING IN THEIR FOOTSTEPS

Five miles of barbed wire fencing and eight guard towers went up three months after Minidoka opened. Center administrators reported "the sudden appearance of the fence was greatly resented by the residents." Much of the fence soon came down and the towers were not staffed.

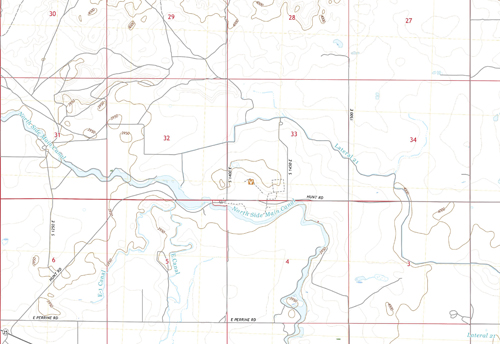

Incarcerees turned the desert into farmland. They produced enough food to share with other camps. After the war, Minidoka lands were subdivided and awarded to land-lottery winners. This agricultural legacy of Minidoka continues today.

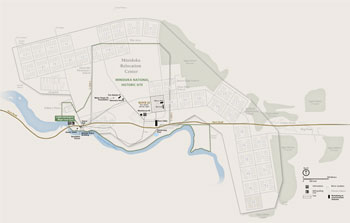

Block 22 As you walk around Block 22, envision all twelve barracks in place plus three other buildings, with 300 people moving about. Imagine walking to the entrance, to the schools, or to visit friends in blocks 1 or 44. (Block 1 is about 3 miles from Block 44.)

At first, everyone dreaded going to the Latrine because the toilets and showers were in open rooms. Resourceful women made stalls out of cardboard or held up sheets for each other to provide some privacy.

The Mess Hall symbolized the changes in their lives. Yaeko Sakai Yoshihara recalls, "When we ate, we ate with friends. And so we didn't eat with our families. It kind of broke down that family unit."

A barrack was a simple tarpaper and wood shelter with six "apartments," each housing two to eight people. Mary Hikata remembers that "one of our neighbor's men was a carpenter, and he went around and made tables for everybody, so at least we had a table and a chair."

The Recreation Hall was a place for classes, plays, dances, and religious services. But a camp administrator said, "So much dust sifts through the cracks of the recreation hall that conversation is carried on under great difficulty."

Block 44 housed Bainbridge Islanders after they arrived in February 1943 from Manzanar. They had asked to be reunited with their relatives and friends from the Pacific Northwest.

Military Police Building Yaeko Sakai Yoshihara, a teenager in the camp, remembers that "people were permitted to get day passes to go to Twin Falls to shop or go see a movie or whatever." She adds, "And then of course you have to come back."

Minidoka War Relocation Center was a 33,000-acre site, but most of its 600 buildings were crowded onto 946 acres. Over 13,000 incarcerees went through Minidoka's gate, with a peak population of 9,397 on March 1, 1943. The camp was the 7th largest "city" in Idaho.

Minidoka was part of my childhood. I would like to see my grandkids understand what happened here.

—Anonymous incarceree speaking at a public hearing

VISITING MINIDOKA TODAY

(click for larger maps) |

This remote land teemed with thousands of men, women, and children between 1942 and 1945. As you visit Minidoka, listen for their voices. Perhaps you will hear echoes of people and events in your own life. Look in the distance to the enduring legacy of the still-active farms. Exhibits along the 1.6-mile trail identify the historic structures and landscape, describe camp life, and explain how the center operated.

Minidoka National Historic Site is a developing national park unit, managed by Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument in Hagerman, Idaho. The historic site, near Jerome, Idaho, is open year-round during daylight hours. Information is available at both locations. Call ahead or check the park website for hours, programs, and activities.

Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial This memorial on Bainbridge Island, Washington, is part of Minidoka National Historic Site. It honors the first Japanese Americans forced from their homes under Executive Order 9066.

The memorial is a joint effort of the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial Association, the Bainbridge Island Historical Museum, the Bainbridge Island Metropolitan Park and Recreation District, the City of Bainbridge Island, and the National Park Service. Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park-Seattle Unit provides National Park Service administrative assistance. For visiting information or tours, contact the Bainbridge Island Historical Museum or go to bainbridgehistory.org or bijac.org.

Safety and Regulations

Wear sturdy footwear, a hat, and sunscreen. • Bring water. • In

winter, check road conditions to the site. • Pets are not allowed on the

trail. • Check the park website for firearms regulations.

Accessibility

We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. For

information go to the Hagerman Visitor Center, call, or check our website.

The National Park Service cares for other sites where Japanese Americans were incarcerated: Manzanar National Historical Site and Tule Lake Unit in California, and Honouliuli National Monument in Hawaii.

Source: NPS Brochure (2015)

|

Establishment

Minidoka National Historic Site — May 8, 2008 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Accessibility Self-Evaluation and Transition Plan, Minidoka National Historic Site, Idaho (April 2019)

Administrative History: Minidoka National Historic Site (Camille Daw and Bob H. Reinhardt, 2024)

An Historiography of Racism: Japanese American Internment, 1942-1945 from Historia, Volume 13 (John Rasel, 2004)

Bainbridge Island Japanese American Memorial, Nidoto Nai Yoni "Let it not happen again", Study of Alternatives/Environmental Assessment (Public Review Draft, Jones & Jones, Spring 2005)

Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites (HTML edition, UW Press 2002 rev. ed.) Western Archeological and Conservation Center Publications in Anthropology 74 (Jeffrey F. Burton, Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord and Richard W. Lord, 1999)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Minidoka Internment National Monument (2007)

Enabling Legislation—Abraham Lincoln National Heritage Area (P.L. 110-229, 122 Stat. 754, 110th Congress, May 8, 2008)

Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast 1942 (J.L. DeWitt, 1943)

Foundation Document, Minidoka National Historic Site, Idaho-Washington (May 2016)

Foundation Document Overview, Minidoka National Historic Site, Idaho-Washington (January 2016)

General Management Plan: Minidoka Internment National Monument (November 2006)

Historic American Buildings Survey

Minidoka Relocation Center Warehouse HABS-ID-131 (Susan M. Stacy, October 31, 2005)

Minidoka Relocation Center, Motor Vehicle and Tire Shop HABS-ID-133 (Christy Avery, 2018)

Historic Resource Study: Minidoka Interment Internment National Monument (Amy Lowe Meger, 2005)

Information Sheet, Minidoka Internment National Monument (undated)

Japanese American Confinement Sites Digital Collection (National Japanese American Historical Society)

Japanese Americans in World War II: National Historic Landmarks Theme Study (Barbara Wyatt, ed., August 2012)

Japanese-American Internment Sites Preservation (January 2001)

Junior Ranger Program, Minidoka National Historic Site (2020; for reference purposes only)

Junior Ranger Program, Minidoka National Historic Site (2021; for reference purposes only)

Junior Ranger Program, Minidoka National Historic Site, Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Lava Ridge Wind Project

Lava Ridge Wind Project Final Environmental Impact Statement — Volume 1 (BLM, June 2024)

Lava Ridge Wind Project Final Environmental Impact Statement — Volume 2 (BLM, June 2024)

Lava Ridge Wind Project Final Environmental Impact Statement — Volume 3 (BLM, June 2024)

Lava Ridge Wind Project Final Environmental Impact Statement — Volume 4a (BLM, June 2024)

Lava Ridge Wind Project Final Environmental Impact Statement — Volume 4b (BLM, June 2024)

Lava Ridge Wind Project Final Environmental Impact Statement — Volume 4c (BLM, June 2024)

Lava Ridge Wind Project Final Environmental Impact Statement — Volume 4d (BLM, June 2024)

Lava Ridge Wind Project Final Environmental Impact Statement — Volume 4e (BLM, June 2024)

Lava Ridge Wind Project Final Environmental Impact Statement — Volume 4f (BLM, June 2024)

Lava Ridge Wind Project Final Environmental Impact Statement — Volume 4g (BLM, June 2024)

Lava Ridge Wind Project Final Environmental Impact Statement — Volume 5a (BLM, June 2024)

Lava Ridge Wind Project Final Environmental Impact Statement — Volume 5b (BLM, June 2024)

Life At Minidoka (Laura Maeda, extract from The Pacific Historian, Vol. 20 No. 4, Winter 1976; ©University of the Pacific for the Holt-Atherton Pacific Center for Western Studies)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan: Minidoka National Historic Site (January 2013)

Minidoka Chronicle

Adjusting (Daniel Quan Design, 2017)

First Impressions: August, 1942 - December, 1942 (Daniel Quan Design, 2017)

Holding our Breath: December, 1941 - July, 1942 (Daniel Quan Design, 2017)

Life Behind the Fence: 1942-1945 (Daniel Quan Design, 2017)

Minidoka Will Always Have Meaning (Daniel Quan Design, 2017)

Moving On: What Comes Next? 1944-1945 (Daniel Quan Design, 2017)

Serving Our Country: 1942-1945 (Daniel Quan Design, 2017)

Minidoka Irrigator (1942-1945)

Minidoka NHS News: v1 n1, January 2015 • v1 n2, February 2015 • v1 n3, March 2015 • v1 n4, April 2015 • v1 n5, May 2015 • v1 n6, June 2015 • v1 n9, October/November 2015 • v1 n11, December 2015 • v2 n1, January 2016 • v2 n2, February 2016 • v2 n3, March 2016 • v2 n4, May-June 2016 • v2 n6, August/September 2016

Modeling Air Quality Impact Potential of a Nearby Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation for Minidoka National Historic Site (Rosa Maria Gómez-Moreno, Joseph Vaughan and Brian Lamb, August 13, 2010)

Museum Management Plan: City of Rocks National Reserve, Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve, Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument, Minidoka Internment National Monument (Robert Applegate, Kent Bush, Brooke Childrey, H. Dale Durham, Phil Gensler, Kirstie Haertel and Diane Nicholson, 2008)

Newsletter (Friends of Minidoka)

Fall 2007 • Spring 2008 • Fall 2008 • Spring 2009 • Fall 2009 • Spring 2010 • Fall 2010 • Spring 2011 • Fall 2011 • Spring 2012 • Fall 2012 • Spring 2013 • Fall 2013 • Spring 2016 • Fall 2016 • Spring 2017 • Fall/Winter 2017 • Spring/Summer 2018 • Spring/Summer 2019 • Fall/Winter 2019 • Fall/Winter 2020 • Spring/Summer 2021 • January 2022

Night Sky Condition Assessment from Minidoka National Historic Site and Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve (Jeremy White, September 15, 2021)

Oral History Interviews

Anna Tamur (Interviewed by Camille Daw, November 10, 2023)

Dan Sakura (Interviewed by Camille Daw, September 15, 2022)

Neil King (Interviewed by Camille Daw, August 4, 2022)

Overview, Minidoka National Historic Site (2009)

Paleontological Resource Inventory and Monitoring, Upper Columbia Basin Network NPS TIC# D-259 (Jason P. Kenworthy, Vincent L. Santucci, Michaleen McNerny and Kathryn Snell, August 2005)

Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Part 1 (HTML edition) (December 1982)

Presidential Proclamation 7395 — Establishment of the Minidoka Internment National Monument (William J. Clinton, January 17, 2001)

The Evacuated People: A Quantitative Description (1946)

The Minidoka Interlude (Residents of Minidoka Relocation Center, September 1942-October 1943)

The Minidoka Irrigator (1942-1945)

This is Minidoka: An Archeological Survey of Minidoka Internment National Monument, Idaho Western Archeological Center Publications in Anthropology No. 80 (Jeffery F. Burton and Mary M. Farrell, 2001)

Words Can Lie or Clarify: Terminology of the World War II Incarceration of Japanese Americans (©Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, 2009)

Words Do Matter: A Note on Inappropriate Terminology and the Incarceration of the Japanese Americans (©Roger Daniels, 2005)

miin/index.htm

Last Updated: 15-Feb-2025