| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

FIRST OFFENSIVE: The Marine Campaign for Guadalcanal by Henry I. Shaw, Jr. September and the Ridge Admiral McCain visited Guadalcanal at the end of August, arriving in time to greet the aerial reinforcements he had ordered forward, and also in time for a taste of Japanese nightly bombing. He got to experience, too, what was becoming another unwanted feature of Cactus nights: bombardment by Japanese cruisers and destroyers. General Vandegrift noted that McCain had gotten a dose of the "normal ration ofshells." The admiral saw enough to signal his superiors that increased support for Guadalcanal operations was imperative and that the "situation admits no delay whatsoever." He also sent a prophetic message to Admirals King and Nimitz: "Cactus can be sinkhole for enemy air power and can be consolidated, expanded, and exploited to the enemy's mortal hurt."

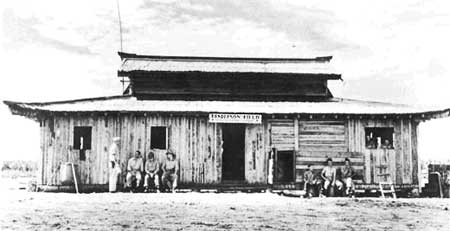

On 3 September, the Commanding General, 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, Brigadier General Roy S. Geiger, and his assistant wing commander, Colonel Louis Woods, moved forward to Guadalcanal to take charge of air operations. The arrival of the veteran Marine aviators provided an instant lift to the morale of the pilots and ground crews. It reinforced their belief that they were at the leading edge of air combat, that they were setting the pace for the rest of Marine aviation. Vandegrift could thankfully turn over the day-to-day management of the aerial defenses of Cactus to the able and experienced Geiger. There was no shortage of targets for the mixed air force of Marine, Army, and Navy flyers. Daily air attacks by the Japanese, coupled with steady reinforcement attempts by Tanaka's destroyers and trrts, meant that every type of plane that could lift off Henderson's runway was airborne as often as possible. Seabees had begun work on a second airstrip, Fighter One, which could relive some of the pressure on the primary airfield.

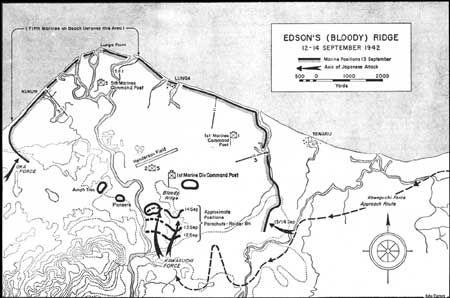

Most of General Kawaguchi's brigade had reached Guadalcanal. Those who hadn't, missed their land-fall forever as a result of American air attacks. Kawaguchi had in mind a surprise attack on the heart of the Marine position, a thrust from the jungle directly at the airfield. To reach his jump-off position, the Japanese general would have to move through difficult terrain unobserved, carving his way through the dense vegetation out of sight of Marine patrols. The rugged approach route would lead him to a prominent ridge topped by Kunai grass which wove snake-like through the jungle to within a mile of Henderson's runway. Unknown to the Japanese, General Vandegrift planned on moving his headquarters to the shelter of a spot at the inland base of this ridge, a site better protected, it was hoped, from enemy bombing and shellfire. The success of Kawaguchi's plan depended upon the Marines keeping the inland perimeter thinly manned while they concentrated their forces on the east and west flanks. This was not to be. Available intelligence, including a captured enemy map, pointed to the likelihood of an attack on the airfield and Vandegrift moved his combined raider-parachute battalion to the most obvious enemy approach route, the ridge. Colonel Edson's men, who scouted Savo Island after moving to Guadalcanal and destroyed a Japanese supply base at Tasimboko in another shore-to-shore raid, took up positions on the forward slopes of the ridge at the edge of the encroaching jungle on 10 September. Their commander later said that he "was firmly convinced that we were in the path of the next Jap attack." Earlier patrols had spotted a sizable Japanese force approaching. Accordingly, Edson patrolled extensively as his men dug in on the ridge and in the flanking jungle. On the 12th, the Marines made contact with enemy patrols confirming the fact the Japanese troops were definitely "out front." Kawaguchi had about 2,000 of his men with him, enough he thought to punch through to me airfield.

Japanese planes had dropped 500-pound bombs along the ridge on the 11th and enemy ships began shelling the area after nightfall on the 12th, once the threat of American air attacks subsided. The first Japanese thrust came at 2100 against Edson's left flank. Boiling out of the jungle, the enemy soldiers attacked fearlessly into the face of rifle and machine gun fire, closing to bayonet range. They were thrown back. They came again, this time against the right flank, penetrating the Marines' positions. Again they were thrown back., A third attack closed out the night's action. Again it was a close affair, but by 0230 Edson told Vandegrift his men could hold. And they did. On the morning of 13 September, Edson called his company commanders together and told them: "They were just testing, just testing. They'll be back." He ordered all positions improved and defenses consolidated and pulled his lines towards the airfield along the ridge's center spine. The 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, his backup on Tulagi, moved into position to reinforce again.

The next night's attacks were as fierce as any man had seen. The Japanese were everywhere, fighting hand-to-hand in the Marines' foxholes and gun pits and filtering past forward positions to attack from the rear. Division Sergeant Major Sheffield Banta shot one in the new command post. Colonel Edson appeared wherever the fighting was toughest, encouraging his men to their utmost efforts. The man-to-man battles lapped over into the jungle on either flank of the ridge, and engineer and pioneer positions were attacked. The reserve from the 5th Marines was fed into the fight. Artillerymen from the 5th Battalion, 11th Marines, as they had on the previous night, fired their 105mm howitzers at any called target. The range grew as short as 1,600 yards from tube to impact. The Japanese finally could take no more. They pulled back as dawn approached. On the slopes of the ridge and in the surrounding jungle they left more than 600 bodies; another 600 men were wounded. The remnants of the Kawaguchi force staggered back toward their lines to the west, a grueling, hellish eight-day march that saw many more of the enemy perish.

The cost to Edson's force for its epic defense was also heavy. Fifty-nine men were dead, 10 were missing in action, and 194 were wounded. These losses, coupled with the casualties of Tulagi, Gavutu, and Tanambogo, meant the end of the 1st Parachute Battalion as an effective fighting unit. Only 89 men of the parachutists' original strength could walk off the ridge, soon in legend to become "Bloody Ridge" or "Edson's Ridge." Both Colonel Edson and Captain Kenneth D. Bailey, commanding the Raider's Company C, were awarded the Medal of Honor for their heroic and inspirational actions. On 13 and 14 September, the Japanese attempted to support Kawaguchi's attack on the ridge with thrusts against the flanks of the Marine perimeter. On the east, enemy troops attempting to penetrate the lines of the 3d Battalion, 1st Marines, were caught in the open on a grass plain and smothered by artillery fire; at least 200 died. On the west, the 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, holding ridge positions covering the coastal road, fought off a determined attacking force that reached its front lines. The victory at the ridge gave a great boost to Allied homefront morale, and reinforced the opinion of the men ashore on Guadalcanal that they could take on anything the enemy could send against them. At upper command echelons, the leaders were not so sure that the ground Marines and their motley air force could hold. Intercepted Japanese dispatches revealed that the myth of the 2,000-man defending force had been completely dispelled. Sizable naval forces and two divisions of Japanese troops were now committed to conquer the Americans on Guadalcanal. Cactus Air Force, augmented frequently by Navy carrier squadrons, made the planned reinforcement effort a high-risk venture. But it was a risk the Japanese were prepared to take.

On 18 September, the long-awaited 7th Marines, reinforced by the 1st Battalion, 11th Marines, and other division troops, arrived at Guadalcanal. As the men from Samoa landed they were greeted with friendly derision by Marines already on the island. The 7th had been the first regiment of the 1st Division to go overseas; its men, many thought then, were likely to be the first to see combat. The division had been careful to send some of its best men to Samoa and now had them back. One of the new and salty combat veterans of the 5th Marines remarked to a friend in the 7th that he had waited a long time "to see our first team get into the game." Providentially, a separate supply convoy reached the island at the same time as the 7th's arrival, bringing with it badly needed aviation gas and the first resupply of ammunition since D-Day. The Navy covering force for the reinforcement and supply convoys was hit hard by Japanese submarines. The carrier Wasp was torpedoed and sunk, the battleship North Carolina (BB-55) was damaged, and the destroyer O'Brien (DD-415) was hit so badly it broke up and sank on its way to drydock. The Navy had accomplished its mission, the 7th Marines had landed, but at a terrible cost. About the only good result of the devastating Japanese torpedo attacks was that the Wasp's surviving aircraft joined Cactus Air Force, as the planes of the Saratoga and Enterprise had done when their carriers required combat repairs. Now, the Hornet (CV-8) was the only whole fleet carrier left in the South Pacific. As the ships that brought the 7th Marines withdrew, they took with them the survivors of the 1st Parachute Battalion and sick bays full of badly wounded men. General Vandegrift now had 10 infantry battalions, one understrength raider battalion, and five artillery battalions ashore; the 3d Battalion, 2d Marines, had come over from Tulagi also. He reorganized the defensive perimeter into 10 sectors for better control, giving the engineer, pioneer, and amphibian tractor battalions sectors along the beach. Infantry battalions manned the other sectors, including the inland perimeter in the jungle. Each infantry regiment had two battalions on line and one in reserve. Vandegrift also had the use of a select group of infantrymen who were training to be scouts and snipers under the leadership of Colonel William J. "Wild Bill" Whaling, and experienced jungle hand, marksman, and hunter, whom he had appointed to run a school to sharpen the division's fighting skills. As men finished their training under Whaling and went back to their outfits, others took their place and the Whaling group was available to scout and spearhead operations. Vandegrift now had enough men ashore on Guadalcanal, 19,200, to expand his defensive scheme. He decided to seize a forward position along the east bank of the Matanikau River, in effect strongly outposting his west flank defenses against the probability of string enemy attacks from the area where most Japanese troops were landing. First, however, he was going to test the Japanese reaction with a strong probing force. He chose the fresh 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Lewis B. "Chesty" Puller, to move inland along the slopes of Mt. Austen and patrol north towards the coast and the Japanese-held area. Puller's battalion ran into Japanese troops bivouacked on the slopes of Austen on the 24th and in a sharp firefight had seven men killed and 25 wounded. Vandegrift sent the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, forward to reinforce Puller and help provide the men needed to carry the casualties out of the jungle. Now reinforced, Puller continued his advance, moving down the east bank of the Matanikau. He reached the coast on the 26th as planned, where he drew intensive fire from enemy positions on the ridges west of the river. An attempt by the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, to cross was beaten back. About the time, the 1st Raider Battalion, its original mission one of establishing a patrol base west of the Matanikau, reached the vicinity of the firefight, and joined in. Vandegrift sent Colonel Edson, now the commander of the 5th Marines, forward to take charge of the expanded force. He was directed to attack on the 27th and decided to send the raiders inland to outflank the Japanese defenders. The battalion, commanded by Edson's former executive officer, Lieutenant Colonel Samuel B. Griffith II, ran into a hornet's nest of Japanese who had crossed the Matanikau during the night. A garbled message led Edson to believe that Griffith's men were advancing according to plan, so he decided to land the companies of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, behind the enemy's Matanikau position and strike the Japanese from the rear while Rosecran's men attacked across the river.

The landing was made without incident and the 7th Marines' companies moved inland only to be ambushed and cut off from the sea by the Japanese. A rescue force of landing craft moved with difficulty through Japanese fire, urged on by Puller who accompanied the boats on the destroyer Ballard (DD-660) [sic: should be DD-267; DD-660 USS Ballard was not commissioned until the following year—ed.]. The Marines were evacuated after fighting their way to the beach covered by the destroyer's fire and the machine guns of a Marine SBD overhead. Once the 7th Marines companies got back to the perimeter, landing near Kukum, the raider and 5th Marines battalions pulled back from the Matanikau. The confirmation that the Japanese would strongly contest any westward advance cost the Marines 60 men killed and 100 wounded.

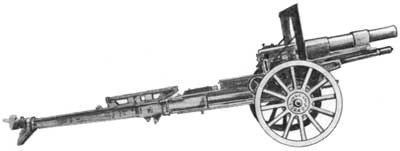

The Japanese the Marines had encountered were mainly men for the 4th Regiment of the 2d (Sendai) Division; prisoners confirmed that the division was landing on the island. Included in the enemy reinforcements were 150mm howitzers, guns capable of shelling the airfield from positions near Kokumbona. Clearly, a new and stronger enemy attack was pending. As September drew to a close, a flood of promotions had reached the division, nine lieutenant colonels put on their colonel's eagles and there were 14 new lieutenant colonels also. Vandegrift made Colonel Gerald C. Thomas, his former operations officer, the new division chief of staff, and had a short time earlier given Edson the 5th Marines. Many of the older, senior officers, picked for the most part in the order they had joined the division, were now sent back to the States. There they would provide a new level of combat expertise in the training and organization of the many Marine units that were forming. The air wing was not quite ready yet to return its experienced pilots to rear areas, but the vital combat knowledge they possessed was much needed in the training pipeline. They, too—the survivors—would soon be rotating back to rear areas, some for a much-needed break before returning to combat and other to lead new squadrons into the fray.

|