| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

FIRST OFFENSIVE: The Marine Campaign for Guadalcanal by Henry I. Shaw, Jr. December and the Final Stages

On 7 December, one year after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, General Vandegrift sent a message to all men under his command in the Guadalcanal area thanking them for their courage and steadfastness, commending particularly the pilots and "all who labored and sweated within the lines in all manner of prodigious and vital tasks." He reminded them all that their "unbelievable achievements had made 'Guadalcanal' a synonym for death and disaster in the language of our enemy." On 9 December, he handed over his command to General Patch and flew out to Australia at the same time the first elements of the 5th Marines were boarding ship. The 1st, 11th, and 7th Marines would soon follow together with all the division's supporting units. The men who were leaving were thin, tired, hollow-eyed, and apathetic; they were young men who had grown old in four months time. They left behind 681 dead in the island's cemetery. The final regiment of the Americal Division, the 132d Infantry, landed on 8 December as the 5th Marines was preparing to leave. The 2d Marine Division's regiments already on the island, the 2d, 8th, and part of the 10th, knew that the 6th Marines was on its way to rejoin. It seemed to many of the men of the 2d Marines, who had landed on D-Day, 7 August, that they, too, should be leaving. These took slim comfort in the thought that they, by all rights, should be the first of the 2d to depart the island whenever that hoped-for day came. General Patch received a steady stream of ground reinforcements and replacements in December. He was not ready yet to undertake a full-scale offensive until the 25th Division and the rest of the 2d Marine Division arrived, but he kept all frontline units active in combat and reconnaissance patrols, particularly toward the western flank. The island commander's air defense capabilities also grew substantially. Cactus Air Force, organized into a fighter command and a strike (bomber) command, now operated from a newly redesignated Marine Corps Air Base. The Henderson Field complex included a new airstrip, Fighter Two, which replaced Fighter One, which had severe drainage problems. Brigadier General Louis Woods, who had taken over as senior aviator when Geiger returned to Espiritu Santo, was relieved on 26 December by Brigadier General Francis P. Mulcahy, Commanding General, 2d Marine Aircraft Wing. New fighter and bomber squadrons from both the 1st and 2d Wings sent their flight echelons forward on a regular basis. The Army added three fighter squadrons and a medium bomber squadron of B-26s. The Royal New Zealand Air Force flew in a reconnaissance squadron of Lockheed Hudsons. And the U.S. Navy sent forward a squadron of Consolidated PBY Catalina patrol planes which had a much needed night-flying capability.

The aerial buildup forced the Japanese to curtail all air attacks and made daylight naval reinforcement attempts an event of the past. The nighttime visits of the Tokyo Express destroyers now brought only supplies encased in metal drums which were rolled over the ships' sides in hope they would float into shore. The men ashore desperately needed everything that could be sent, even by this method, but most of the drums never reached the beaches. Still, however desperate the enemy situation was becoming, he was prepared to fight. General Hyakutake continued to plan the seizure of the airfield. General Hitoshi Immamura, commander of the Eighth Area Army, arrived in Rabaul on 2 December with orders to continue the offensive. He had 50,000 men to add to the embattled Japanese troops on Guadalcanal. Before these new enemy units could be employed, the Americans were prepared to move out from the perimeter in their own offensive. Conscious that the Mt. Austen area was a continuing threat to his inland flank in any drive to the west, Patch committed the Americal's 132d Infantry to the task of clearing the mountain's wooded slopes on 17 December. The Army regiment succeeded in isolating the major Japanese force in the area by early January. The 1st Battalion, 2d Marines, took up hill positions to the southeast of the 132d to increase flank protection. By this time, the 25th Infantry Division (Major General J. Lawton Collins) had arrived and so had the 6th Marines (6 January) and the rest of the 2d Division's headquarters and support troops. Brigadier General Alphonse De Carre, the Marine division's assistant commander, took charge of all Marine ground forces on the island. The 2d Division's commander, Major General John Marston, remained in New Zealand because he was senior to General Patch. With three divisions under his command, General Patch was designated Commanding General, XIV Corps, on 2 January. His corps headquarters numbered less than a score of officers and men, almost all taken from the Americal's staff. Brigadier General Edmund B. Sebree, who had already led both Army and Marine units in attacks on the Japanese, took command of the Americal Division. On 10 January, Patch gave the signal to start the strongest American offensive yet in the Guadalcanal campaign. The mission of the troops was simple and to the point: "Attack and destroy the Japanese forces remaining on Guadalcanal."

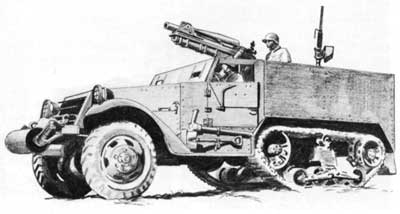

The initial objective of the corps' attack was a line about 1,000 to 1,500 yards west of jump-off positions. These ran inland from Point Cruz to the vicinity of Hill 66, about 3,000 yards from the beach. In order to reach Hill 66, the 25th Infantry Division attacked first with the 35th and 27th Infantry driving west and southwest across a scrambled series of ridges. The going was rough and the dug-in enemy, elements of two regiments of the 38th Division, gave way reluctantly and slowly. By the 13th, however, the American soldiers, aided by Marines of the 1st Battalion, 2d Marines, had won through to positions on the southern flank of the 2d Marine Division. On 12 January, the Marines began their advance with the 8th Marines along the shore and 2d Marines inland. At the base of Point Cruz, in the 3d Battalion, 8th Marines' sector, regimental weapons company half-tracks ran over seven enemy machine gun nests. The attack was then held up by an extensive emplacement until the weapons company commander, Captain Henry P. "Jim" Crowe, took charge of a half-dozen Marine infantrymen taking cover from enemy fire with the classic remarks: "You'll never get a Purple Heart hiding in a fox hole. Follow me!" The men did and they destroyed the emplacement. All along the front of the advancing assault companies the going was rough. The Japanese, remnants of the Sendai Division, were dug into the sides of a series of cross compartments and their fire took the Marines in the flank as they advanced. Progress was slow despite massive artillery support and naval gunfire from four destroyers offshore. In two days of heavy fighting, flamethrowers were employed for the first time and tanks were brought into play. The 2d Marines was now relieved and the 6th Marines moved into the attack along the coast while the 8th Marines took up the advance inland. Naval gunfire support, spotted by naval officers ashore, improved measurably. On the 15th, the Americans, both Army and Marine, reached the initial corps objective. In the Marine attack zone, 600 Japanese were dead.

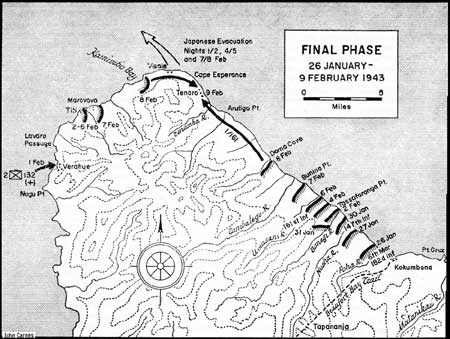

The battle-weary 2d Marines had seen its last infantry action of Guadalcanal. A new unit now came into being, a composite Army-Marine division, or CAM division, formed from units of the Americal and 2d Marine Divisions. The directing staff was from the 2d Division, since the Americal had responsibility for the main perimeter. Two of its regiments, the 147th and the 182d Infantry, moved up to attack in line with the 6th Marines still along the coast. The 8th Marines was essentially pinched out of the front lines by a narrowing attack corridor as the inland mountains and hills pressed closer to the coastal trail. The 25th Division, which was advancing across this rugged terrain, had the mission of outflanking the Japanese in the vicinity of Kokumbona, while the CAM Division drove west. On the 23d, as the CAM troops approached Kokumbona, the 1st Battalion of the 27th Infantry struck north out of the hills and overran the village site and Japanese base. There was only slight but steady opposition to the American advance as the enemy withdrew west toward Cape Esperance. The Japanese had decided, reluctantly, to give up the attempt to retake Guadalcanal. The orders were sent in the name of the Emperor and senior staff officers were sent to Guadalcanal to ensure their acceptance. The Navy would make the final runs of the Tokyo Express, only this time in reverse, to evacuate the garrison so it could fight again in later battles to hold the Solomons. Receiving intelligence that enemy ships were massing again to the northwest, General Patch took steps, as Vandegrift had before him on many occasions, to guard against overextending his forces in the face of what appeared to be another enemy attempt at reinforcement. He pulled the 25th Division back to bolster the main perimeter defenses and ordered the CAM Division to continue its attack. When the Marines and soldiers moved out on 26 January, they had a surprisingly easy time of it, gaining 1,000 yards the first day and 2,000 the following day. The Japanese were still contesting every attack, but not in strength. By 30 January, the sole frontline unit in the American advance was the 147th Infantry; the 6th Marines held positions to its left rear. The Japanese destroyer transports made their first run to the island on the night of 1-2 February, taking out 2,300 men from evacuation positions near Cape Esperance. On the night of 4-5 February, they returned and took out most of the Sendai survivors and General Hyakutake and his Seventeenth Army staff. The final evacuation operation was carried out on the night of 7-8 February, when a 3,000-man rear guard was embarked. In all, the Japanese withdrew about 11,000 men in those three nights and evacuated about 13,000 soldiers from Guadalcanal overall. The Americans would meet many of these men again in later battles, but not the 600 evacuees who died, too worn and sick to survive their rescue.

On 9 February, American soldiers advancing from east and west met at Tenaro village on Cape Esperance. The only Marine ground unit still in action was the 3d Battalion, 10th Marines, supporting the advance. General Patch could happily report the "complete and total defeat of Japanese forces on Guadalcanal." Nor organized Japanese units remained. On 31 January, the 2d Marines and the 1st Battalion, 8th Marines, boarded ship to leave Guadalcanal. As was true with the 1st Marine Division, some of these men were so debilitated by malaria they had to be carried on board. All of them struck observers again as young men grown old "with their skins cracked and furrowed and wrinkled." On 9 February, the rest of the 8th Marines and a good part of the division supporting units boarded transports. The 6th Marines, thankfully only six weeks on the island, left on the 19th. All were headed for Wellington, New Zealand, the 2d Marines for the first time. Left behind on the island as a legacy of the 2d Marine Division were 263 dead. The total cost of the Guadalcanal campaign to the American ground combat forces was 1,598 officers and men killed, 1,152 of them Marines. The wounded totaled 4,709, and 2,799 of these were Marines. Marine aviation casualties were 147 killed and 127 wounded. The Japanese in their turn lost close to 25,000 men on Guadalcanal, about half of whom were killed in action. The rest succumbed to illness, wounds, and starvation. At sea, the comparative losses were about equal, with each side losing about the same number of fighting ships. The enemy loss of 2 battleships, 3 carriers, 12 cruisers, and 25 destroyers, was irreplaceable. The Allied ships losses, though costly, were not fatal; in essence, all ships lost were replaced. In the air, at least 600 Japanese planes were shot down; even more costly was the death of 2,300 experienced pilots and aircrewmen. The Allied plane losses were less than half the enemy's number and the pilot and aircrew losses substantially lower.

President Roosevelt, reflecting the thanks of a grateful nation, awarded General Vandegrift the Medal of Honor for "outstanding and heroic accomplishment" in his leadership of American forces on Guadalcanal from 7 August to 9 December 1942. And for the same period, he awarded the Presidential Unit Citation to the 1st Marine Division (Reinforced) for "outstanding gallantry" reflecting "courage and determination ... of an inspiring order." Included in the division's citation and award, besides the organic units of the 1st Division, were the 2d and 8th Marines and attached units of the 2d Marine Division, all of the Americal Division, the 1st Parachute and 1st and 2d Raider Battalions, elements of the 3d, 5th, and 14th Defense Battalions, the 1st Aviation Engineer Battalion, the 6th Naval Construction Battalion, and two motor torpedo boat squadrons. The indispensable Cactus Air Force was included, also represented by 7 Marine headquarters and service squadrons, 16 Marine flying squadrons, 16 Navy flying squadrons, and 5 Army flying squadrons. The victory at Guadalcanal marked a crucial turning point in the Pacific War. No longer were the Japanese on the offensive. Some of the Japanese Emperor's best infantrymen, pilots, and seamen had been bested in close combat by the Americans and their Allies. There were years of fierce fighting ahead, but there was now no question of its outcome. When the veterans of the 1st Marine Division were gathered in thankful reunion 20 years later, they received a poignant message from Guadalcanal. The sender was a legend to all "Canal" Marines, Honorary U.S. Marine Corps Sergeant Major Jacob C. Vouza. The Solomons native in his halting English said: "Tell them I love them all. Me old man now, and me no look good no more. But me never forget."

|