| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

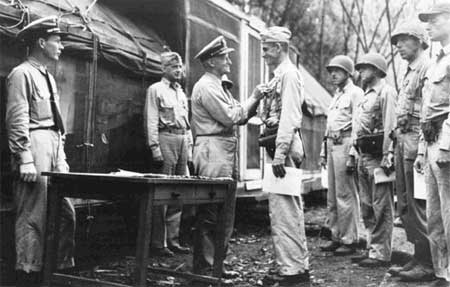

FIRST OFFENSIVE: The Marine Campaign for Guadalcanal by Henry I. Shaw, Jr. October and the Japanese Offensive On 30 September, unexpectedly, a B-17 carrying Admiral Nimitz made an emergency landing at Henderson Field. The CinCPac made the most of the opportunity. He visited the front lines, saw Edson's Ridge, and talked to a number of Marines. He reaffirmed to Vandegrift that his overriding mission was to hold the airfield. He promised all the support he could give and after awarding Navy Crosses to a number of Marines, including Vandegrift, left the next day visibly encouraged by what he had seen.

The next Marine move involved a punishing return to the Matanikau, this time with five infantry battalions and the Whaling group. Whaling commanded his men and the 3d Battalion, 2d Marines, in a thrust inland to clear the way for two battalions of the 7th Marines, the 1st and 2d, to drive through and hook toward the coast, hitting the Japanese holding along the Matanikau. Edson's 2d and 3d Battalions would attack across the river mouth. All the division's artillery was positioned to fire in support. On the 7th, Whaling's force moved into the jungle about 2,000 yards upstream on the Matanikau, encountering Japanese troops that harassed his forward elements, but not in enough strength to stop the advance. He bypassed the enemy positions and dug in for the night. Behind him the 7th Marines followed suit, prepared to move through his lines, cross the river, and attack north toward the Japanese on the 8th. The 5th Marines' assault battalions moving toward the Matanikau on the 7th ran into Japanese in strength about 400 yards from the river. Unwittingly, the Marines had run into strong advance elements of the Japanese 4th Regiment, which had crossed the Matanikau in order to establish a base form which artillery could fire into the Marine perimeter. The fighting was intense and the 3d Battalion, 5th, could make little progress, although the 2d Battalion encountered slight opposition and won through to the river bank. It then turned north to hit the inland flank of the enemy troops. Vandegrift sent forward a company of raiders to reinforce the 5th, and it took a holding position on the right, towards the beach.

Rain poured down on the 8th, all day long, virtually stopping all forward progress, but not halting the close-in fighting around the Japanese pocket. The enemy troops finally retreated, attempting to escape the gradually encircling Marines. They smashed into the raider's position nearest to their escape route. A wild hand-to-hand battle ensued and a few Japanese broke through to reach and cross the river. The rest died fighting. On the 9th, Whaling's force, flanked by the 2d and then the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, crossed the Matanikau and then turned and followed ridge lines to the sea. Puller's battalion discovered a number of Japanese in a raving to his front, fired his mortars, and called in artillery, while his men used rifles and machine guns to pick off enemy troops trying to escape what proved to be a death trap. When his mortar ammunition began to run short, Puller moved on toward the beach, joining the rest of Whaling's force, which had encountered no opposition. The Marines then recrossed the Matanikau, joined Edson's troops, and marched back to the perimeter, leaving a strong combat outpost at the Matanikau, now cleared of Japanese. General Vandegrift, apprised by intelligence sources that a major Japanese attack was coming from the west, decided to consolidate his positions, leaving no sizable Marine force more than a day's march from the perimeter. The Marine advance on 7-9 October had thwarted Japanese plans for an early attack and cost the enemy more than 700 men. The Marines paid a price too, 65 dead and 125 wounded.

There was another price that Guadalcanal was exacting from both sides. Disease was beginning to fell men in numbers that equalled the battle casualties. In addition to gastroenteritis, which greatly weakened those who suffered its crippling stomach cramps, there were all kinds of tropical fungus infections, collectively known as "jungle rot," which produced uncomfortable rashes on men's feet, armpits, elbows, and crotches, a product of seldom being dry, If it didn't rain, sweat provided the moisture. On top of this came hundreds of cases of malaria. Atabrine tablets provided some relief, besides turning the skin yellow, but they were not effective enough to stop the spread of the mosquito-borne infection. malaria attacks were so pervasive that nothing sort of complete prostration, becoming a litter case, could earn a respite in the hospital. naturally enough, all these diseases affected most strongly the men who had been on the island the longest, particularly those who experienced the early days of short rations. Vandegrift had already argued with his superiors that when his men eventually got relieved they should not be sent to another tropical island hospital, but rather to a place where there was a real change of atmosphere and climate. He asked that Auckland or Wellington, New Zealand, be considered. For the present, however, there was to be no relief for men starting their third month on Guadalcanal. The Japanese would not abandon their plan to seize back Guadalcanal and gave painful evidence of their intentions near mid-October. General Hyakutake himself landed on Guadalcanal on 7 October to oversee the coming offensive. Elements of Major General Masao Maruyama's Sendai Division, already a factor in the fighting near the Matanikau, landed with him More men were coming. And the Japanese, taking advantage of the fact that Cactus flyers had no night attack capability, planned to ensure that no planes at all would rise from Guadalcanal to meet them. On 11 October, U.S. Navy surface ships took a hand in stopping the "Tokyo Express," the nickname that had been given to Admiral Tanaka's almost nightly reinforcement forays. A covering force of five cruisers and five destroyers, located near Rennell Island and commanded by Rear Admiral Norman Scott, got word that many ships were approaching Guadalcanal. Scott's mission was to protect an approaching reinforcement convoy and he steamed toward Cactus at flank speed eager to engage. He encountered more ships than he had expected, a bombardment group of three heavy cruisers and two destroyers, as well as six destroyers escorting two seaplane carrier transports. Scott maneuvered between Savo Island and Cape Esperance, Guadalcanal's western tip, and ran head-on into the bombardment group.

Alerted by a scout plane from his flagship, San Francisco (CA-38), spottings later confirmed by radar contacts on the Helena (CL-50), the Americans opened fire before the Japanese, who had no radar, knew of their presence. One enemy destroyer sank immediately, two cruisers were badly damaged, one, the Furutaka, later foundered, and the remaining cruiser and destroyer turned away from the inferno of American fire. Scott's own force was punished by enemy return fire which damaged two cruisers and two destroyers, one of which, the Duncan (DD-485), sank the following day. On the 12th too, Cactus flyers spotted two of the reinforcement destroyer escorts retiring and sank them both. The Battle of Cape Esperance could be counted an American naval victory, one sorely needed at the time. Its way cleared by Scott's encounter with the Japanese, a really welcome reinforcement convoy arrived at the island on 13 October when the 164th Infantry of the Americal Division arrived. The soldiers, members of a National Guard outfit originally from North Dakota, were equipped with Garand M-1 rifles, a weapon of which most overseas Marines had only heard. In rate of fire, the semiautomatic Garand could easily outperform the single-shot, bolt-action Springfields the Marines carried and the bolt-action rifles the Japanese carried, but most 1st Division Marines of necessity touted the Springfield as inherently more accurate and a better weapon. This did not prevent some light-fingered Marines from acquiring Garands when the occasion present itself. And such an occasion did present itself while the soldiers were landing and their supplies were being moved to dumps. Several flights of Japanese bombers arrived over Henderson Field, relatively unscathed by the defending fighters, and began dropping their bombs. The soldiers headed for cover and alert Marines, inured to the bombing, used the interval to "liberate" interesting cartons and crates. The news that the Army had arrived spread across the island like wildfire, for it meant to all marines that they eventually would be relieved. There was hope. As if the bombing was not enough grief, the Japanese opened on the airfield with their 150mm howitzers also. Altogether the men of the 164th got a rude welcome to Guadalcanal. And on that night, 13-14 October, they shared a terrifying experience with the Marines that no one would ever forget.

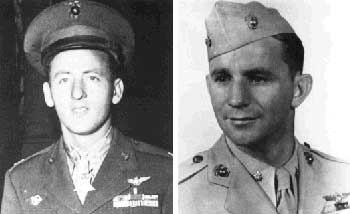

Determined to knock out Henderson Field and protect their soldiers landing in strength west of Koli Point, the enemy commanders sent the battleships Kongo and Haruna into Ironbottom Sound to bombard the Marine positions. The usual Japanese flare planes heralded the bombardment, 80 minutes of sheer hell which had 14-inch shells exploding with such effect that the accompanying cruiser fire was scarcely noticed. No one was safe; no place was safe. No dugout had been built to withstand 14-inch shells. One witness, a seasoned veteran demonstrably cool under enemy fire, opined that there was nothing worse in war than helplessly being on the receiving end of naval gunfire. He remembered "huge trees being cut apart and flying about like toothpicks." And he was on the front lines, not the prime enemy target. The airfield and its environs were a shambles when dawn broke. The naval shelling, together with the night's artillery fire and bombing, had left Cactus Air Force's commander, General Geiger, with a handful of aircraft still flyable, and airfield thickly cratered by shells and bombs, and a death toll of 41. Still, from Henderson or Fighter One, which now became the main airstrip, the Cactus Flyers had to attack, for the morning also revealed a shore and sea full of inviting targets. The expected enemy convoy had gotten through and Japanese transports and landing craft were everywhere near Tassafaronga. At sea the escorting cruisers and destroyers provided a formidable antiaircraft screen. Every American plane that could fly did. General Geiger's aide, Major Jack Cram, took off in the general's PBY, hastily rigged to carry two torpedoes, and put one of them into the side of an enemy transport as it was unloading. He landed the lumbering flying boat with enemy aircraft hot on his tail. A new squadron of F4Fs, VMF-212, commanded by Major Harold W. Bauer, flew in during the day's action, landed, refueled, and took off to join the fighting. An hour later, Bauer landed again, this time with four enemy bombers to his credit. Bauer, who added to his score of Japanese aircraft kills in later air battles, was subsequently lost in action. He was awarded the Medal of Honor, as were four other Marine pilots of the early Cactus Air Force: Captain Jefferson J. DeBlank (VMF-112); Captain Joseph J. Foss (VMF-121); Major Robert E. Galer (VMF-224); and Major John L. Smith (VMF-223).

The Japanese had landed more than enough troops to destroy the Marine beachhead and seize the airfield. At least General Hyakutake thought so, and he heartily approved General Maruyama's plan to move most of the Sendai Division through the jungle, out of sight and out of contact with the Marines, to strike from the south in the vicinity of Edson's Ridge. Roughly 7,000 men, each carrying a mortar or artillery shell, started along the Maruyama Trail which had been partially hacked out of the jungle well inland from the Marine positions. Maruyama, who had approved the trail's name to indicate his confidence, intended to support this attack with heavy mortars and infantry guns (70mm pack howitzers). The men who had to lug, push, and drag these supporting arms over the miles of broken ground, across two major streams, the Matanikau and the Lunga, and through heavy underbrush, might have had another name for their commander's path to supposed glory.

General Vandegrift knew the Japanese were going to attack. Patrols an reconnaissance flights had clearly indicated the push would be from the west, where the enemy reinforcements had landed. The American commander changed his dispositions accordingly. There were Japanese troops east of the perimeter, too, but not in any significant strength. The new infantry regiment, the 164th, reinforced by Marine special weapons units, was put into the line to hold the eastern flank along 6,600 yards, curving inland to join up with the 7th Marines near Edson's Ridge. The 7th held 2,500 yards from the ridge to the Lunga. From the Lunga, the 1st Marines had a 3,500-yard sector of jungle running west to the point where the line curved back to the beach again in the 5th Marines' sector. Since the attack was expected from the west, the 3d Battalions of each of the 1st and 7th Marines held a strong outpost position forward of the 5th Marines' lines along the east bank of the Matanikau. In the lull before the attack, if a time of patrol clashes, Japanese cruiser-destroyer bombardments, bomber attacks, and artillery harassment could properly be called a lull, Vandegrift was visited by the Commandant of the Marine Corps, Lieutenant General Thomas Holcomb. The Commandant flew in on 21 October to see for himself how his Marines were faring. It also proved to be an occasion for both senior Marines to meet the new ComSoPac, Vice Admiral William F. "Bull" Halsey. Admiral Nimitz had announced Halsey's appointment on 18 October and the news was welcome in Navy and Marine ranks throughout the Pacific. Halsey's deserved reputation for élan and aggressiveness promised renewed attention to he situation on Guadalcanal. On the 22d, Holcomb and Vandegrift flew to Noumea to meet with Halsey and to receive and give a round of briefings on the Allied situation. After Vandegrift had described his position, he argued strongly against the diversion of reinforcements intended for Cactus to any other South Pacific venue, a sometime factor of Admiral Turner's strategic vision. He insisted that he needed all of the Americal Division and another 2d Marine Division regiment to beef up his forces, and that more than half of his veterans were worn out by three months' fighting and the ravages of jungle-incurred diseases. Admiral Halsey told the Marine general: "You go back there, Vandegrift. I promise to get you everything I have."

When Vandegrift returned to Guadalcanal, Holcomb moved on to Pearl Harbor to meet with Nimitz, carrying Halsey's recommendation that, in the future, landing force commanders once established ashore, would have equal command status with Navy amphibious force commanders. At Pearl, Nimitz approved Halsey's recommendation—which Holcomb had drafted—and in Washington so did King. In effect the, the command status of all future Pacific amphibious operations was determined by the events of Guadalcanal. Another piece of news Vandegrift received from Holcomb also boded well for the future of the Marine Corps. Holcomb indicated that if President Roosevelt did not reappoint him, unlikely in view of his age and two terms in office, he would recommend that Vandegrift be appointed the next Commandant.

This new of future events had little chance of diverting Vandegrift's attention when he flew back to Guadalcanal, for the Japanese were in the midst of their planned offensive. On the 20th, an enemy patrol accompanied by two tanks tried to find a way through the line held by Lieutenant Colonel William N. McKelvy, Jr.'s 3d Battalion, 1st Marines. A sharpshooting 37mm gun crew knocked out one tank and the enemy force fell back, meanwhile shelling the Marine positions with artillery. Near sunset the next day, the Japanese tried again, this time with more artillery fire and more tanks in the fore, but again a 37mm gun knocked out a lead tank and discouraged the attack. On 22 October, the enemy paused, waiting for Maruyama's force to get into position inland. On the 23d, planned as the day of the Sendai's main attack, the Japanese dropped a heavy rain of artillery and mortar fire on McKelvy's positions near the Matanikau River mouth. Near dusk, nine 18-tom medium tanks clanked out of the trees onto the river's sandbar and just as quickly eight of them were riddled by the 37s. One tank got across the river, a marine blasted a track off with a grenade, and a 75mm half-track finished it off in the ocean's surf. The following enemy infantry was smothered by Marine artillery fire as all battalions of the augmented 11th Marines rained shells on the massed attackers. Hundreds of Japanese were casualties and three more tanks were destroyed. Later, an inland thrust further upstream was easily beaten back. The abortive coastal attack did almost nothing to aid Maruyama's inland offensive, but did cause Vandegrift to shift one battalion, the 2d Battalion, 7th Marines, out of the line to the east and into the 4.000-yard gap between the Matanikau position and the perimeter. This moved proved providential since one of Maruyama's planned attacks was headed right for this area.

Although patrols had encountered no Japanese east or south of the jungled perimeter up to the 24th, the Matanikau attempts had alerted everyone. When General Maruyama finally was satisfied that his men had struggled through to appropriate assault positions, after delaying his day of attack three times, he was ready on 24 October. The Marines were waiting. An observer from the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, spotted an enemy officer surveying Edson's Ridge on the 24th, and scout-snipers reported smoke from numerous rice fires rising from a valley about two miles south of Lieutenant Colonel Puller's positions. Six battalions of the Sendai Division were poised to attack, and near midnight the first elements of the enemy hit and bypassed a platoon-sized outpost forward of Puller's barbed-wire entanglements. Warned by the outpost, Puller's men waited, straining to see through a dark night and a driving rain. Suddenly, the Japanese charged out of the jungle, attacking in Puller's area near the ridge and the flat ground to the east. The Marine replied with everything they had, calling in artillery, firing mortars, relying heavily on crossing fields of machine gun fire to cut down the enemy infantrymen. Thankfully, the enemy's artillery, mortars, and other supporting arms were scattered back along the Maruyama Trail; they had proved too much of a burden for the infantrymen to carry forward. A wedge was driven into the Marine lines, but eventually straightened out with repeated counterattacks. Puller soon realized his battalion was being hit by a strong Japanese force capable of repeated attacks. He called for reinforcements and the Army's 3d Battalion, 164th Infantry (Lieutenant Colonel Robert K. Hall), was ordered forward, its men sliding and slipping in the rain as they trudged a mile south along Edson's Ridge. Puller met Hall at the head of his column, and the two officers walked down the length of the Marine lines, peeling off an Army squad at a time to feed into the lines. When the Japanese attacked again as they did all night long, the soldiers and Marines fought back together. By 0330, the Army battalion was completely integrated into the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines'; lines and the enemy attacks were getting weaker and weaker. The American return fire—including flanking fire from machine guns and Weapons Company, 7th Marines' 37mm guns remaining in the positions held by 2d Battalion, 164th Infantry, on Puller's left—was just too much to take. Near dawn, Maruyama pulled his men back to regroup and prepare to attack again.

With daylight, Puller and Hall reordered the lines, putting the 3d Battalion, 164th, into its own positions on Puller's left, tying in with the rest of the Army regiment. The driving rains had turned Fighter One into a quagmire, effectively grounding Cactus flyers. Japanese planes used the "free ride" to bomb Marine positions. Their artillery fired incessantly and a pair of Japanese destroyers added their gunfire to the bombardment until they got too close to the shore and the 3d Defense Battalion's 5-inch guns drove them off. As the sun bore down, the runways dried and afternoon enemy attacks were met by Cactus fighters, who downed 22 Japanese planes with a loss of three of their own. As night came on again, Maruyama tried more of the same, with the same result. The Army-Marine lines held and the Japanese were cut down in droves by rifle, machine gun, mortar, 37mm, and artillery fire. To the west, an enemy battalion mounted three determined attacks against the positions held by Lieutenant Colonel Herman H. Hanneken's 2d Battalion, 7th Marines, thinly tied in with Puller's battalion on the left and the 3d Battalion, 7th Marines, on the right. The enemy finally penetrated the positions held by Company F, but a counterattack led by Major Odell M. Conoley, the battalion's executive officer, drove off the Japanese. Again at daylight the American positions were secure and the enemy had retreated. They would not come back; the grand Japanese offensive of the Sendai Division was over. About 3,500 enemy troops had died during the attacks. General Maruyama's proud boast that he "would exterminate the enemy around the airfield in one blow" proved an empty one. What was left of his force now straggled back over the Maruyama Trail, losing, as had the Kawaguchi force in the same situation, most of its seriously wounded men. The Americans, Marines and soldiers together, probably lost 300 men killed and wounded; existing records are sketchy and incomplete. One result of the battle, however, was a warm welcome to the 164th Infantry from the 1st Marine Division. Vandegrift particularly commended Lieutenant Colonel Hall's battalion, stating the "division was proud to have serving with it another unit which had stood the test of battle." And Colonel Cates sent a message to the 164th's Colonel Bryant Moore saying that the 1st Marines "were proud to serve with a unit such as yours." Amidst all the heroics of the two nights' fighting there were many men who were singled out for recognition and an equally large number who performed great deeds that were never recognized. Two men stood out above all others, and on succeeding nights, Sergeant John Basilone of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, and Platoon Sergeant Mitchell Paige of the 2d Battalion, both machine gun section heads, were recognized as having performed "above and beyond the call of duty" in the inspiring words of their Medal of Honor citations.

|