| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

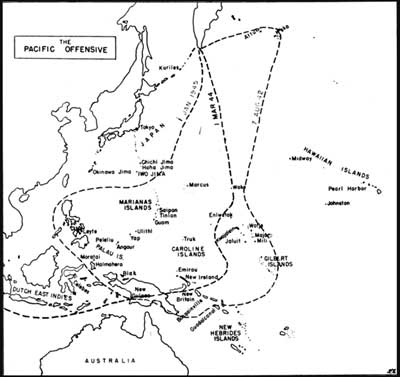

CLOSING IN: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander U.S. Marine Corps (Ret) Sunday, 4 March 1945, marked the end of the second week of the U.S. invasion of Iwo Jima. By this point the assault elements of the 3d, 4th, and 5th Marine Divisions were exhausted, their combat efficiency reduced to dangerously low levels. The thrilling sight of the American flag being raised by the 28th Marines on Mount Suribachi had occurred 10 days earlier, a lifetime on "Sulphur Island." The landing forces of the V Amphibious Corps (VAC) had al ready sustained 13,000 casualties, including 3,000 dead. The "front lines" were a jagged serration across Iwo's fat northern half, still in the middle of the main Japanese defenses. Ahead the going seemed all uphill against a well-disciplined, rarely visible enemy.

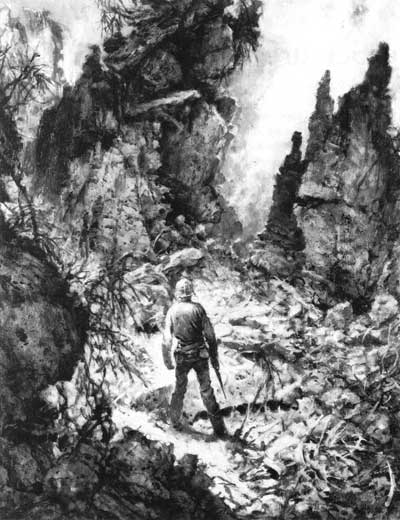

In the center of the island, the 3d Marine Division units had been up most of the night repelling a small but determined Japanese counterattack which had found the seam between the 21st and 9th Marines. Vicious close combat had cost both sides heavy casualties. The counterattack spoiled the division's preparations for a morning advance. Both regiments made marginal gains against very stiff opposition. To the east the 4th Marine Division had finally captured Hill 382, ending its long exposure in "The Amphitheater," but combat efficiency had fallen to 50 percent. It would drop another five points by nightfall. On this day the 24th Marines, supported by flame tanks, advanced a total of 100 yards, pausing to detonate more than a ton of explosives against enemy cave positions in that sector. The 23d and 25th Marines entered the most difficult terrain yet encountered, broken ground that limited visibility to only a few feet. Along the western flank, the 5th Marine Division had just seized Nishi Ridge and Hill 362-B the previous day, suffering more than 500 casualties. It too had been up most of the night engaging a sizeable force of infiltrators. The Sunday morning attacks lacked coordination, reflecting the division's collective exhaustion. Most rifle companies were at half strength. The net gain for the day, the division reported, was "practically nil."

But the battle was beginning to take its toll on the Japanese garrison as well. General Tadamichi Kuribayashi knew his 109th Division had inflicted heavy casualties on the attacking Marines, yet his own losses had been comparable. The American capture of the key hills in the main defense sector the day before deprived him of his invaluable artillery observation sites. His brilliant chief of artillery, Colonel Chosaku Kaido, lay dying. On this date Kuribayashi moved his own command post from the central highlands to a large cave on the northwest coast. The usual blandishments from Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo reached him by radio that afternoon, but Kuribayashi was in no mood for heroic rhetoric. "Send me air and naval support and I will hold the island;' he signaled. "Without them I cannot hold." That afternoon the fighting men of both sides witnessed a harbinger of Iwo Jima's fate. Through the overcast skies appeared a gigantic silver bomber, the largest aircraft anyone had ever seen. It was the Boeing B-29 Super Fortress "Dinah Might," crippled in a raid over Tokyo, seeking an emergency landing on the island's scruffy main airstrip. As the Americans in the vicinity held their breaths, the big bomber swooped in from the south, landed heavily, clipped a field telephone pole with a wing, and shuddered to a stop less than 50 feet from the bitter end of the strip. Pilot Lieutenant Fred Malo and his 10-man crew were extremely glad to be alive, but they didn't stay long. Every Japanese gunner within range wanted to bag this prize. Mechanics made field repairs within a half hour. Then the 65-ton Superfort lumbered aloft through a hail of enemy fire and headed back to its base in Tinian. The Marines cheered. The battle of Iwo Jima would rage on for another 22 days, claiming eleven thousand more American casualties and the lives of virtually the entire Japanese garrison. This was a colossal fight between two well-armed, veteran forces—the biggest and bloodiest battle in the history of the United States Marine Corps. From the 4th of March on, however, the leaders of both sides entertained no doubts as to the ultimate outcome.

|