| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

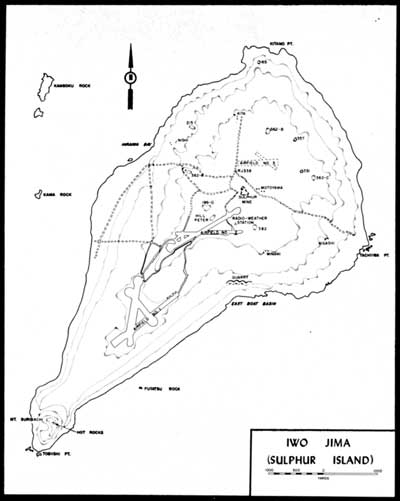

CLOSING IN: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander U.S. Marine Corps (Ret) Assault Preparations Iwo Jima was one of those rare amphibious landings where the assault troops could clearly see the value of the objective. They were the first ground units to approach within a thousand miles of the Japanese homeland, and they were participating directly in the support of the strategic bombing campaign. The latter element represented a new wrinkle on an old theme. For 40 years the U.S. Marines had been developing the capability for seizing advanced naval bases in support of the fleet. Increasingly in the Pacific War—and most especially at Saipan, Tinian, and now Iwo Jima—they were seizing advanced airbases to further the strategic bombing of the Japanese home islands. American servicemen had awaited the coming of the B-29s for years. The "very-long-range" bombers, which had become operational too late for the European War, had been striking mainland Japan since November 1944. Results proved disappointing. The problem stemmed not from the pilots or planes but rather from a vexing little spit of volcanic rock lying halfway along the direct path from Saipan to Tokyo—Iwo Jima. Iwo's radar gave the Japanese defense authorities two hours advance notice of every B-29 strike. Japanese fighters based on Iwo swarmed up to harass the unescorted Superforts going in and especially coming home, picking off those bombers crippled by antiaircraft (AA) fire. As a result, the B-29s had to fly higher, along circuitous routes, with a reduced payload. At the same time, enemy bombers based on Iwo often raided B-29 bases in the Marianas, causing some damage. The Joint Chiefs of Staff decided Iwo Jima must be captured and a U.S. airbase built there. This would eliminate Japanese bombing raids and the early warning interceptions, provide fighter escorts throughout the most dangerous portion of the long B-29 missions, and enable greater payloads at longer ranges. Iwo Jima in American hands would also provide a welcome emergency field for crippled B-29s returning from Tokyo. It would also protect the flank of the pending invasion of Okinawa. In October 1944 the Joint Chiefs directed Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, CinCPac, to seize and develop Iwo Jima within the ensuing three months. This launched Operation Detachment. The first enemy in the campaign would prove to be the island itself, an ugly, barren, foul-smelling chunk of volcanic sand and rock, barely 10 square miles in size. Iwo Jima means "Sulphur Island" in Japanese. As described by one Imperial Army staff officer, the place was "an island of sulphur, no water, no sparrow, no swallow." Less poetic American officers saw Iwo's resemblance to a pork chop, with the 556-foot dormant volcano Mount Suribachi dominating the narrow southern end, overlooking the only potential landing beaches. To the north, the land rose unevenly onto the Motoyama Plateau, falling off sharply along the coasts into steep cliffs and canyons. The terrain in the north represented a defender's dream: broken, convoluted, cave-dotted, a "jungle of stone." Wreathed by volcanic steam, the twisted landscape appeared ungodly, almost moon-like. More than one surviving Marine compared the island to something out of Dante's Inferno. Forbidding Iwo Jima had two redeeming features in 1945: the military value of its airfields and the psychological status of the island as a historical possession of Japan. Iwo Jima lay in Japan's "Inner Vital Defense Zone" and was in fact administered as part of the Tokyo Prefecture. In the words of one Japanese officer, "Iwo Jima is the doorkeeper to the Imperial capital." Even by the slowest aircraft, Tokyo could be reached in three flight hours from Iwo. In the battle for Iwo Jima, a total of 28,000 Americans and Japanese would give their lives in savage fighting during the last winter months of 1945. No one on the American side ever suggested that taking Iwo Jima would be an easy proposition. Admiral Nimitz assigned this mission to the same team which had prevailed so effectively in the earlier amphibious assaults in the Gilberts, Marshalls, and Marianas: Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, commanding the Fifth Fleet; Vice Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, commanding the Expeditionary Forces; and Rear Admiral Harry W. Hill, commanding the Attack Force. Spruance added the highly regarded Rear Admiral William H. P. Blandy, a veteran of the Peleliu/Angaur landings, to command the Amphibious Support Forces, responsible for minesweeping, underwater demolition team operations, and preliminary naval air and gun bombardment. As usual, "maintaining unremitting military pressure on the enemy" meant an accelerated planning schedule and an overriding emphasis on speed of execution. The amphibious task force preparing to assault Iwo Jima soon found itself squeezed on both ends. Hill and Blandy had a critical need for the amphibious ships, landing craft, and shore bombardment vessels currently being used by General Douglas MacArthur in his reconquest of Luzon in the Philippines. But bad weather and stiff enemy resistance combined to delay completion of that operation. The Joint Chiefs reluctantly postponed D-day for Iwo Jima from 20 January 1945 until 19 February. The tail end of the schedule provided no relief. D-Day for Okinawa could go no later than 1 April because of the approach of the monsoon season. The constricted time frame for Iwo would have grave implications for the landing force. The experienced V Amphibious Corps under Major General Harry Schmidt, USMC, would provide the landing force, an unprecedented assembly of three Marine divisions, the 3d, 4th, and 5th. Schmidt would have the distinction of commanding the largest force of U.S. Marines ever committed in a single battle, a combined force which eventually totalled more than 80,000 men. Well above half of these Marines were veterans of earlier fighting in the Pacific; realistic training had prepared the newcomers well. The troops assaulting Iwo Jima were arguably the most proficient amphibious forces the world had seen. Unfortunately, two senior Marines shared the limelight for the Iwo Jima battle, and history has often done both an injustice. Spruance and Turner prevailed upon Lieutenant General Holland M. Smith, then commanding Fleet Marine Forces, Pacific, to participate in Operation Detachment as Commanding General, Expeditionary Troops. This was a gratuitous billet. Schmidt had the rank, experience, staff, and resources to execute corps-level responsibility without being second-guessed by another headquarters. Smith, the amphibious pioneer and veteran of landings in the Aleutians, Gilberts, Marshalls, and Marianas, admitted to being embarrassed by the assignment. "My sun had almost set by then," he stated, "I think they asked me along only in case something happened to Harry Schmidt." Smith tried to keep out of Schmidt's way, but his subsequent decision to withhold commitment of the 3d Marines, the Expeditionary Troops reserve, remains as controversial today as it was in 1945.

Holland Smith was an undeniable asset to the Iwo Jima campaign. During the top-level planning stage he was often, as always, a "voice in the wilderness," predicting severe casualties unless greater and more effective preliminary naval bombardment was provided. He diverted the press and the visiting dignitaries from Schmidt, always providing realistic counterpoints to some of the rosier staff estimates. "It's a tough proposition," Smith would say about Iwo, "That's why we are here." General Schmidt, whose few public pronouncements left him saddled with the unfortunate prediction of a 10-day conquest of Iwo Jima, came to resent the perceived role Holland Smith played in post-war accounts. As he would forcibly state:

General Smith would not disagree with those points. Smith provided a useful role, but Schmidt and his exceptional staff deserve maximum credit for planning and executing the difficult and bloody battle of Iwo Jima.

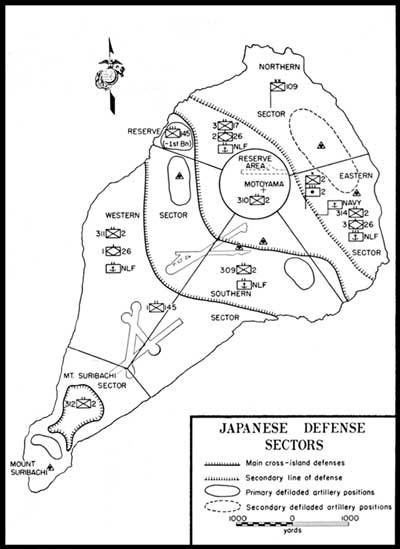

The V Amphibious Corps achievement was made even more memorable by the enormously difficult opposition provided by the island and the enemy. In Lieutenant General Tadamichi Kuribayashi [see sidebar], the Americans faced one of the most formidable opponents of the war. A fifth-generation samurai, hand picked and personally extolled by the Emperor, Kuribayashi combined combat experience with an innovative mind and an iron will. Although this would be his only combat against American forces, he had learned much about his prospective opponents from earlier service in the United States. More significantly, he could appraise with an unblinking eye the results of previous Japanese attempts to repel American invasions of Japanese-held garrisons. Heroic rhetoric aside, Kuribayashi saw little to commend the "defend-at-the- water's-edge" tactics and "all-or-nothing" Banzai attacks which had characterized Japan's failures from Tarawa to Tinian. Kuribayashi, a realist, also knew not to expect much help from Japan's depleted fleet and air forces. His best chances, he concluded, would be to maximize Iwo's forbidding terrain with a defense in depth, along the pattern of the recent Biak and Peleliu defensive efforts. He would eschew coast defense, anti-landing, and Banzai tactics and instead conduct a prolonged battle of attrition, a war of nerves, patience, and time. Possibly the Americans would lose heart and abandon the campaign. Such a seemingly passive policy, even that late in the war, seemed revolutionary to senior Japanese Army and Navy leaders. It ran counter to the deeply ingrained warrior code, which viewed the defensive as only an unpleasant interim pending resumption of the glorious offensive in which one could destroy the enemy with sword and bayonet. Even Imperial General Headquarters grew nervous. There is some evidence of a top-level request for guidance in defending against American "storm landings" from Nazi Germany, whose sad experience in trying to defend Normandy at the water's edge had proven disastrous. The Japanese remained unconvinced. Kuribayashi needed every bit of his top connections with the Emperor to keep from being summarily relieved for his radical proposals. His was not a complete organizational victory—the Navy insisted on building gun casemates and blockhouses along the obvious landing beaches on Iwo—but in general he prevailed. Kuribayashi demanded the assistance of the finest mining engineers and fortifications specialists in the Empire. Here again, the island favored the defender. Iwo's volcanic sand mixed readily with cement to produce superior concrete for installations; the soft rock lent itself to rapid digging. Half the garrison lay aside their weapons to labor with pick and spade. When American heavy bombers from the Seventh Air Force commenced a daily pounding of the island in early December 1944, Kuribayashi simply moved everything—weapons, command posts, barracks, aid stations—under ground. These engineering achievements were remarkable. Masked gun positions provided interlocking fields of fire, miles of tunnels linked key defensive positions, every cave featured multiple outlets and ventilation tubes. One installation inside Mount Suribachi ran seven stories deep. The Americans would rarely see a live Japanese on Iwo Jima until the bitter end. American intelligence experts, aided by documents captured in Saipan and by an almost daily flow of aerial photography (and periscope-level pictures from the submarine Spearfish), puzzled over the "disappearing act" of the Japanese garrison. Trained photo interpreters, using stereoscopic lenses, listed nearly 700 potential targets, but all were hardened, covered, masked. The intelligence staffs knew there was no fresh water available on the island. They could see the rainwater cisterns and they knew what the average monthly rainfall would deliver. They concluded the garrison could not possibly survive under those conditions in numbers greater than 12,000 or 13,000. But Kuribayashi's force was twice that size. The men existed on half-rations of water for months before the battle began. Unlike earlier amphibious assaults at Guadalcanal and Tarawa, the Americans would not enjoy either strategic or tactical surprise at Iwo Jima. Japanese strategists concluded Iwo Jima would be invaded soon after the loss of the Marianas. Six months before the battle, Kuribayashi wrote his wife, "The Americans will surely invade this Iwo Jima . . . do not look for my return." He worked his men ruthlessly to complete all defensive and training preparations by 11 February 1945—and met the objective. His was a mixed force of veterans and recruits, soldiers and sailors. His artillerymen and mortar crews were among the best in the Empire. Regardless, he trained and disciplined them all. As the Americans soon discovered, each fighting position contained the commander's "Courageous Battle Vows" prominently posted above the firing apertures. Troops were admonished to maintain their positions and exact 10 American lives for every Japanese death. General Schmidt issued VAC Operation Plan 5-44 on 23 December 1944. The plan offered nothing fancy. Mount Suribachi dominated both potential beaches, but the 3,000 yards of black sand along the southeastern coast appeared more sheltered from the prevailing winds. Here the V Amphibious Corps would land on D-day, the 4th Marine Division on the right, the 5th on the left, the 3d in reserve. The initial objectives included the lower airfield, the west coast, and Suribachi. Then the force would swing into line and attack north, shoulder to shoulder. Anticipation of a major Japanese counterattack the first night influenced the landing plan. "We welcome a counterattack," said Holland Smith, "That's generally when we break their backs." Both Schmidt and 4th Marine Division commander Major General Clifton B. Cates knew from recent experience at Tinian how capable the Japanese were at assembling large reserves at potential soft points along a fresh beachhead. The assault divisions would plan to land their artillery regiments before dark on D-day in that contingency.

The physical separation of the three divisions, from Guam to Hawaii, had no adverse effect on preparatory training. Where it counted most—the proficiency of small units in amphibious landings and combined-arms assaults on fortified positions—each division was well prepared for the forthcoming invasion. The 3d Marine Division had just completed its participation in the successful recapture of Guam; field training often extended to active combat patrols to root out die-hard Japanese survivors. In Maui, the 4th Marine Division prepared for its fourth major assault landing in 13 months with quiet confidence. Recalled Major Frederick J. Karch, operations officer for the 14th Marines, "we had a continuity there of veterans that was just unbeatable." In neighboring Hawaii, the 5th Marine Division calmly prepared for its first combat experience. The unit's newness would prove misleading. Well above half of the officers and men were veterans, including a number of former Marine parachutists and a few Raiders who had first fought in the Solomons. Lieutenant Colonel Donn J. Robertson took command of the 3d Battalion, 27th Marines, barely two weeks before embarkation and immediately ordered it into the field for a sustained live-firing exercise. Its competence and confidence impressed him. "These were professionals," he concluded.

Among the veterans preparing for Iwo Jima were two Medal of Honor recipients from the Guadalcanal campaign, Gunnery Sergeant John "Manila John" Basilone and Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Galer. Headquarters Marine Corps preferred to keep such distinguished veterans in the states for morale purposes, but both men wrangled their way back overseas—Basilone leading a machine gun platoon, Galer delivering a new radar unit for employment with the Landing Force Air Support Control Unit. The Guadalcanal veterans would only shake their heads at the abundance of amphibious shipping available for Operation Detachment. Admiral Turner would command 495 ships, of which fully 140 were amphibiously configured, the whole array 10 times the size of Guadalcanal's task force. Still there were problems. So many of the ships and crews were new that each rehearsal featured embarrassing collisions and other accidents. The new TD-18 bulldozers were found to be an inch too wide for the medium landing craft (LCMs). The newly modified M4A3 Sherman tanks proved so heavy that the LCMs rode with dangerously low freeboards. Likewise, 105mm howitzers overloaded the amphibious trucks (DUKWs) to the point of near unseaworthiness. These factors would prove costly in Iwo's unpredictable surf zone. These problems notwithstanding, the huge force embarked and began the familiar move to westward. Said Colonel Robert E. Hogaboom, Chief of Staff, 3d Marine Division, "we were in good shape, well trained, well equipped and thoroughly supported." On Iwo Jima, General Kuribayashi had benefitted from the American postponements of Operation Detachment because of delays in the Philippines campaign. He, too, felt as ready and prepared as possible. When the American armada sailed from the Marianas on 13 February, he was forewarned. He deployed one infantry battalion in the vicinity of the beaches and lower airfield, ordered the bulk of his garrison into its assigned fighting holes, and settled down to await the inevitable storm. Two contentious issues divided the Navy-Marine team as D-day at Iwo Jima loomed closer. The first involved Admiral Spruance's decision to detach Task Force 58, the fast carriers under Admiral Marc Mitscher, to attack strategic targets on Honshu simultaneously with the onset of Admiral Blandy's preliminary bombardment of Iwo. The Marines suspected Navy-Air Force rivalry at work here—most of Mitscher's targets were aircraft factories which the B-29s had missed badly a few days earlier. What the Marines really begrudged was Mitscher taking all eight Marine Corps fighter squadrons, assigned to the fast carriers, plus the new fast battleships with their 16-inch guns. Task Force 58 returned to Iwo in time to render sparkling support with these assets on D-day, but two days later it was off again, this time for good. The other issue was related and it concerned the continuing argument between senior Navy and Marine officers over the extent of preliminary naval gunfire. The Marines looked at the intelligence reports on Iwo and requested 10 days of preliminary fire. The Navy said it had neither the time nor the ammo to spare; three days would have to suffice. Holland Smith and Harry Schmidt continued to plead, finally offering to compromise to four days. Turner deferred to Spruance who ruled that three days prep fires, in conjunction with the daily pounding being administered by the Seventh Air Force, would do the job. Lieutenant Colonel Donald M. Weller, USMC, served as the FMFPAC/Task Force 51 naval gun fire officer, and no one in either sea service knew the business more thoroughly. Weller had absorbed the lessons of the Pacific War well, especially those of the conspicuous failures at Tarawa. The issue, he argued forcibly to Admiral Turner, was not the weight of shells nor their caliber but rather time. Destruction of heavily fortified enemy targets took deliberate, pinpoint firing from close ranges, assessed and adjusted by aerial observers. Iwo Jima's 700 "hard" targets would require time to knock out, a lot of time.

Neither Spruance nor Turner had time to give, for strategic, tactical, and logistical reasons. Three days of firing by Admiral Blandy's sizeable bombardment force would deliver four times the amount of shells Tarawa received, and one and a half times that delivered against larger Saipan. It would have to do.

In effect, Iwo's notorious foul weather, the imperviousness of many of the Japanese fortifications, and other distractions dissipated even the three days' bombardment. "We got about thirteen hours' worth of fire support during the thirty-four hours of available daylight," complained Brigadier General William W. Rogers, chief of staff to General Schmidt. The Americans received an unexpected bonus when General Kuribayashi committed his only known tactical error during the battle. This occurred on D-minus-2, as a force of 100 Navy and Marine underwater demolition team (UDT) frogmen bravely approached the eastern beaches escorted by a dozen LCI landing craft firing their guns and rockets. Kuribayashi evidently believed this to be the main landing and authorized the coastal batteries to open fire. The exchange was hot and heavy, with the LCIs getting the worst of it, but U.S. battleships and cruisers hurried in to blast the casemate guns suddenly revealed on the slopes of Suribachi and along the rock quarry on the right flank.

That night, gravely concerned about the hundreds of Japanese targets still untouched by two days of firing, Admiral Blandy conducted a "council of war" on board his flagship. At Weller's suggestion, Blandy junked the original plan and directed his gunships to concentrate exclusively on the beach areas. This was done with considerable effect on D minus-1 and D-day morning itself. Kuribayashi noted that most of the positions the Imperial Navy insisted on building along the beach approaches had in fact been destroyed, as he had predicted. Yet his main defensive belts criss-crossing the Motoyama Plateau remained intact. "I pray for a heroic fight," he told his staff. On board Admiral Turner's flagship, the press briefing held the night before D-day was uncommonly somber. General Holland Smith predicted heavy casualties, possibly as many as 15,000, which shocked all hands. A man clad in khakis without rank insignia then stood up to address the room. It was James V. Forrestal, Secretary of the Navy. "Iwo Jima, like Tarawa, leaves very little choice," he said quietly, "except to take it by force of arms, by character and courage."

|