| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

CLOSING IN: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander U.S. Marine Corps (Ret) The Drive North The landing force still had much to learn about its opponent. Senior intelligence officers did not realize until 27 February, the ninth day of the battle, that General Kuribayashi was in fact on Iwo Jima, or that his fighters actually numbered half again the original estimate of 13,000. For Kuribayashi, the unexpectedly early loss of the Suribachi garrison represented a setback, yet he occupied a position of great strength. He still had the equivalent of eight infantry battalions, a tank regiment, two artillery and three heavy mortar battalions, plus the 5,000 gunners and naval infantry under his counterpart, Rear Admiral Toshinosuke Ichimaru. Unlike other besieged garrisons in the Central Pacific, the two Japanese services on Iwo Jima functioned well together. Kuribayashi was particularly pleased with the quality of his artillery and engineering troops. Colonel Chosaku Kaido served as Chief of Artillery from his seemingly impregnable concrete blockhouse on a promontory on the east central sector of the Motoyama Plateau, a lethal landmark the Marines soon dubbed "Turkey Knob," Major General Sadasue Senda, a former artillery officer with combat experience in China and Manchuria, commanded the 2d Independent Mixed Brigade, whose main units would soon be locked into a 25-day death struggle with the 4th Marine Division. Kuribayashi knew that the 204th Naval Construction Battalion had built some of the most daunting defensive systems on the island in that sector. One cave had a tunnel 800 feet long with 14 separate exits; it was one of hundreds designed to be defended in depth. The Japanese defenders waiting for the advance of the V Amphibious Corps were well armed and confident. Occasionally Kuribayashi authorized company-sized spoiling attacks to recapture lost terrain or disrupt enemy assault preparations. These were not suicidal or sacrificial. Most were preceded by stinging artillery and mortar fires and aimed at limited objectives. Kuribayashi's iron will kept his troops from large-scale, wasteful Banzai attacks until the last days. One exception occurred the night of 8 March when General Senda grew so frustrated at the tightening noose being applied by the 4th Marine Division that he led 800 of his surviving troops in a ferocious counterattack. Finally given a multitude of open targets, the Marines cut them down in a lingering melee.

For the first week of the drive north, the Japanese on Iwo Jima actually had the attacking Marines outgunned. Japanese 150mm howitzers and 120mm mortars were superior to most of the weapons of the landing force. The Marines found the enemy direct fire weapons to be equally deadly, especially the dual-purpose antiaircraft guns and the 47mm tank guns, buried and camouflaged up to their turrets. "The Japs could snipe with those big guns," said retired Lieutenant General Donn J. Robertson. The defenders also had the advantage of knowing the ground. Not surprisingly, most casualties in the first three weeks of the battle resulted from high explosives: mortars, artillery, mines, grenades, and the hellacious rocket bombs. Time correspondent Robert Sherrod reported that the dead at Iwo Jima, both Japanese and American, had one thing in common: "They all died with the greatest possible violence. Nowhere in the Pacific War had I seen such badly mangled bodies. Many were cut squarely in half." Close combat was rough enough; on Iwo Jima the stress seemed end less because for a long time the Marines had no secure "rear area" in which to give shot-up troop units a respite. Kuribayashi's gunners throughout the Motoyama Plateau could still bracket the beaches and airfields. The enormous spigot mortar shells and rocket bombs still came tumbling out of the sky. Japanese infiltrators were drawn to "softer targets" in the rear. Anti-personnel mines and booby traps, encountered here on a large scale for the first time in the Pacific, seemed everywhere. Exhausted troop units would stumble out of the front lines seeking nothing more than a helmet-full of water in which to bathe and a deep hole in which to sleep. Too often the men had to spend their rare rest periods repairing weapons, humping ammo, dodging major-caliber incoming, or having to repel yet another nocturnal Japanese probe.

General Schmidt planned to attack the Japanese positions in the north with three divisions abreast, the 5th on the left, the 3d (less the 3d Marines) in the center, and the 4th on the right, along the east coast. The drive north officially began on D+5, the day after the capture of Suribachi. Prep fires along the high ground immediately north of the second airfield extended for a full hour. Then three regimental combat teams moved out abreast, the 26th Marines on the left, the 24th Marines on the right, and the 21st Marines again in the middle. For this attack, General Schmidt consolidated the Sherman tanks of all three divisions into one armored task force commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William R. "Rip" Collins. It would be the largest concentration of Marine tanks in the war, virtually an armored regiment. The attack plan seemed solid. The Marines soon realized they were now trying to force passage through Kuribayashi's main defensive belt. The well-coordinated attack degenerated into desperate, small-unit actions all along the front. The 26th Marines on the left, aided by the tanks, gained the most yardage, but it was all relative. The airfield runways proved to be lethal killing zones. Marine tanks were bedeviled by mines and high-velocity direct fire weapons all along the front. On the right flank, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander A. Vandegrift, Jr., son of the Commandant, became a casualty. Major Doyle A. Stout took command of the 3d Battalion, 24th Marines.

During the fighting on D+5, General Schmidt took leave of Admiral Hill and moved his command post ashore from the amphibious force flagship Auburn (AGC 10). Colonel Howard N. Kenyon led his 9th Marines ashore and into a staging area. With that, General Erskine moved the command post of the 3d Marine Division ashore; the 21st Marines reverted to its parent command. Erskine's artillery regiment, the 12th Marines under Lieutenant Colonel Raymond F. Crist, Jr., continued to land for the next several days. Schmidt now had eight infantry regiments committed. Holland Smith still retained the 3d Marines in Expeditionary Troops reserve. Schmidt made the first of several requests to Smith for release of this seasoned outfit. The V Amphibious Corps had already suffered 6,845 casualties.

The next day, D+6, 25 February, provided little relief in terms of Japanese resistance. Small groups of Marines, accompanied by tanks, somehow made it across the runway, each man harboring the inescapable feeling he was alone in the middle of a gigantic bowling alley. Sometimes holding newly gained positions across the runway proved more deadly than the process of getting there. Resupply became nearly impossible. Tanks were invaluable; many were lost. Schmidt this day managed to get on shore the rest of his corps artillery, two battalions of 155mm howitzers under Colonel John S. Letcher. Well directed fire from these heavier field pieces eased some of the pressure. So did call fire from the cruisers and destroyers assigned to each maneuver unit. But the Marines expressed disappointment in their air support. The 3d Marine Division complained that the Navy's assignment of eight fighters and eight bombers on station was "entirely inadequate." By noon on this date General Cates sent a message to Schmidt requesting that "the Strategic Air Force in the Marianas replace Navy air support immediately." Colonel Vernon E. Megee, now ashore as Air Commander Iwo Jima and taking some of the heat from frustrated division commanders, blamed "those little spit-kit Navy fighters up there, trying to help, never enough, never where they should be." In fairness, it is doubtful whether any service could have provided effective air support during the opening days of the drive north. The Air Liaison Parties with each regiment played hell trying to identify and mark targets, the Japanese maintained masterful camouflage, front-line units were often "eyeball-to-eyeball" with the enemy, and the air support request net was overloaded. The Navy squadrons rising from the decks of escort carriers improved thereafter, to the extent that their conflicting missions would permit. Subsequent strikes featured heavier bombs (up to five hundred pounds) and improved response time. A week later General Cates rated his air support "entirely satisfactory." The battle of Iwo Jima, however, would continue to frustrate all providers of supporting arms; the Japanese almost never assembled legitimate targets in the open. "The Japs weren't on Iwo Jima," said Captain Fields of the 26th Marines, "they were in Iwo Jima." Richard Wheeler, who survived service with the 28th Marines and later wrote two engrossing books about the battle, pointed out this phenomenon:

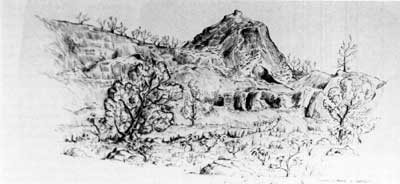

As the Marines struggled to wrest the second airfield from the Japanese, the commanding terrain features rising to the north caught their attention. Some would become known by their elevations (although there were three Hill 362s on the island), but others would take the personality and nicknames assigned by the attackers. Hence, the 4th Marine Division would spend itself attacking Hill 382, the "Amphitheater," and "Turkey Knob" (the whole bristling complex became known as "The Meatgrinder"). The 5th Division would earn its spurs and lose most of its invaluable cadre of veteran leaders attacking Nishi Ridge and Hills 362-A and 362-B, then end the fighting in "The Gorge." The 3d Division would focus first on Hills Peter and 199-Oboe, just north of the second airfield, then the heavily fortified Hill 362-C beyond the third airstrip, and finally the moonscape jungle of stone which would become know as "Cushman's Pocket." Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Cushman, Jr., a future Commandant, commanded the 2d Battalion, 9th Marines at Iwo Jima. Cushman and his men were veterans of heavy fighting in Guam, yet they were appalled by their first sight of the battlefield. Wrecked and burning Sherman tanks dotted the airstrips, a stream of casualties flowed to the rear, "the machine-gun fire was terrific." Cushman mounted his troops on the surviving tanks and roared across the field. There they met the same reverse-slope defenses which had plagued the 21st Marines. Securing the adjoining two small hills—Peter and 199-Oboe—took the 3d Marine Division three more days of intensely bitter fighting.

General Schmidt, considering the 3d Division attack in the center to be his main effort, provided priority fire support from Corps artillery, and directed the other two divisions to allocate half their own regimental fire support to the center. None of the commanders was happy with this. Neither the 4th Division, taking heavy casualties in The Amphitheater as it approached Hill 382, nor the 5th Division, struggling to seize Nishi Ridge, wanted to dilute their organic fire support. Nor was General Erskine pleased with the results. The main effort, he argued, should clearly receive the main fire. Schmidt never did solve this problem. His Corps artillery was too light; he needed twice as many battalions and bigger guns—up to 8-inch howitzers, which the Marine Corps had not yet fielded. He had plenty of naval gun fire support available and used it abundantly, but unless the targets lay in ravines facing to the sea he lost the advantage of direct, observed fire.

Schmidt's problems of fire support distribution received some alleviation on 26 February when two Marine observation planes flew in from the escort carrier Wake Island, the first aircraft to land on Iwo's recaptured and still fire-swept main airstrip. These were Stinson OY single-engine observation planes, nicknamed "Grasshoppers," of Lieutenant Tom Rozga's Marine Observation Squadron (VMO) 4, and they were followed the next day by similar planes from Lieutenant Roy G. Miller's VMO-5. The intrepid pilots of these frail craft had already had an adventurous time in the waters off Iwo Jima. Several had been launched precariously from the experimental Brodie catapult on LST 776, "like a peanut from a slingshot." All 14 of the planes of these two observation squadrons would receive heavy Japanese fire in battle, not only while airborne but also while being serviced on the airstrips as well. Yet these two squadrons (and elements of VMO-1) would fly nearly 600 missions in support of all three divisions. Few units contributed so much to the eventual suppression of Kuribayashi's deadly artillery fire. In time the mere presence of these small planes overhead would influence Japanese gunners to cease fire and button up against the inevitable counterbattery fire to follow. Often the pilots would undertake pre-dawn or dusk missions simply to extend this protective "umbrella" over the troops, risky flying given Iwo's unlit fields and constant enemy sniping from the adjacent hills.

The 4th Marine Division finally seized Hill 382, the highest point north of Suribachi, but continued to take heavy casualties moving through The Amphitheater against Turkey Knob. The 5th Division overran Nishi Ridge, then bloodied itself against Hill 362-As intricate defenses. Said Colonel Thomas A. Wornham, commanding the 27th Marines, of these defenses: "They had interlocking bands of fire the likes of which you never saw." General Cates redeployed the 28th Marines into this slugfest. On 2 March a Japanese gunner fired a high-velocity shell which killed Lieutenant Colonel Chandler Johnson immediately, one week after his glorious seizure of Suribachi's summit. The 28th Marines captured Hill 362-A at the cost of 200 casualties. On the same day Lieutenant Colonel Lowell E. English, commanding the 2d Battalion, 21st Marines, went down with a bullet through his knee. English was bitter. His battalion was being rotated to the rear. "We had taken very heavy casualties and were pretty well disorganized. I had less than 300 men left out of the 1200 I came ashore with." English then received orders to turn his men around and plug a gap in the front lines. "It was an impossible order. I couldn't move that disorganized battalion a mile back north in 30 minutes." General Erskine did not want excuses. "You tell that damned English he'd better be there, he told the regimental commander. English fired back, "You tell that son of a bitch I will be there, and I was, but my men were still half a mile behind me and I got a blast through the knee." On the left flank, the 26th Marines mounted its most successful, and bloodiest, attack of the battle, finally seizing Hill 362-B. The day-long struggle cost 500 Marine casualties and produced five Medals of Honor. For Captain Frank C. Caldwell, commanding Company F, 2d Battalion, 26th Marines it was the worst single day of the battle. His company suffered 47 casualties in taking the hill, including the first sergeant and the last of the original platoon commanders. Overall, the first nine days of the V Amphibious Corps drive north had produced a net gain of about 4,000 yards at the staggering cost of 7,000 American casualties. Several of the pitched battles—Airfield No. 2, Hill 382, Hill 362-B, for example—would of themselves warrant a separate commemorative monograph. The fighting in each case was as savage and bloody as any in Marine Corps history. This was the general situation previously described at the unsuspected "turning point" on 4 March (D+13) when, despite sustaining frightful losses, the Marines had chewed through a substantial chunk of Kuribayashi's main defenses, forcing the enemy commander to shift his command post to a northern cave. This was the afternoon the first crippled B-29 landed. In terms of American morale, it could not have come at a better time. General Schmidt ordered a general standdown on 5 March to enable the exhausted assault forces a brief respite and the opportunity to absorb some replacements.

The issue of replacement troops during the battle remains controversial even half a century later. General Schmidt, now faced with losses approaching the equivalent of one entire division, again urged General Smith to release the 3d Marines. While each division had been assigned a replacement draft of several thousand Marines, Schmidt wanted the cohesion and combat experience of Colonel James M. Stuart's regimental combat team. Holland Smith believed that the replacement drafts would suffice, presuming that each man in these hybrid units had received sufficient infantry training to enable his immediate assignment to front-line outfits. The problem lay in distributing the replacements in small, arbitrary numbers—not as teamed units—to fill the gaping holes in the assault battalions. The new men, expected to replace invaluable veterans of the Pacific War, were not only new to combat, but they also were new to each other, an assortment of strangers lacking the life saving bonds of unit integrity. "They get killed the day they go into battle," said one division personnel officer in frustration. Replacement losses within the first 48 hours of combat were, in fact, appalling. Those who survived, who learned the ropes and established a bond with the veterans, contributed significantly to the winning of the battle. The division commanders, however, decried the wastefulness of this policy and urged unit replacements by the veteran battalions of the 3d Marines. As General Erskine recalled:

Most surviving senior officers agreed that the decision not to use the 3d Marines at Iwo Jima was ill advised and costly. But Holland Smith never wavered: "Sufficient troops were on Iwo Jima for the capture of the island . . . . two regiments were sufficient to cover the front assigned to General Erskine." On 5 March, D+14, Smith ordered the 3d Marines to sail back to Guam. Holland Smith may have known the overall statistics of battle losses sustained by the landing force to that point, but he may not have fully appreciated the tremendous attrition of experienced junior officers and senior staff noncommissioned officers taking place every day. As one example, the day after the 3d Marines, many of whose members were veterans of Bougainville and Guam, departed the amphibious objective area, Company E, 2d Battalion, 23d Marines, suffered the loss of its seventh company commander since the battle began. Likewise, Lieutenant Colonel Cushman's experiences with the 2d Battalion, 9th Marines, seemed typical:

Lieutenant Colonel English recalled that by the 12th day the 2d Battalion, 21st Marines, had "lost every company commander . . . . I had one company exec left." Lieutenant Colonel Donn Robertson, commanding the 3d Battalion, 27th Marines, lost all three of his rifle company commanders, "two killed by the same damned shell." In many infantry units, platoons ceased to exist; depleted companies were merged to form one half-strength outfit.

|