|

Yellowstone National Park: Its Exploration and Establishment Biographical Appendix |

|

WILLIAM A. BAKER. Born in County Donegal, Ireland, in 1832; died Mar. 31, 1874, at Fort Ellis, Montana Territory. The sergeant of the military escort that accompanied the Washburn party through the Yellowstone region in 1870.

He was an itinerant peddler prior to his enlistment Nov. 6, 1854, in Company F, Second Dragoons (the Second U.S. Cavalry after 1861). The enlistment papers describe him as 5 feet 8-1/2 inches in height, with blue eyes, brown hair, and a fair complexion.

Sergeant Baker earned his stripes in rough campaigning during the Civil War, and thus was a well-seasoned noncommissioned officer—experienced with all manner of men, as well as in formal and Indian warfare. He was quiet, efficient, and well-liked, and he should have retired from his beloved Company F as a senior NCO at the conclusion of a long and faithful service; instead, he was killed by Private James Murphy in the course of the latter's murderous attack upon a comrade in the barracks at Fort Ellis.

Sources: The National Archives, RG-94, AGO—Enlistment papers and register, and "Homocide at Fort Ellis," in the Bozeman, Mont. Avant Courier, Apr. 3, 1875, p. 3. Followup items appear in the issues of September 18 and 25.

JOHN WHITNEY BARLOW. Born in Wyoming County, N.Y., June 26, 1838; died Feb. 27, 1914, at Jerusalem, Palestine. The engineer officer in charge of the Army's 1871 party of Yellowstone explorers and co-author of the official report.

Entering West Point as a cadet in 1856, he graduated with the class of 1861 (2 months early because of the fall of Fort Sumter). He was commissioned a second lieutenant of artillery on May 6 and employed as an instructor of volunteer troops until May 15, when he received a commission as first lieutenant.

He took part in the Battle of Bull Run and served through the Peninsula Campaign with Battery M, Second U.S. Artillery. His gallant and meritorious service at the battle of Hanover Court House, Va., earned him the brevet rank of captain.

On June 13, 1863, Captain Barlow was given command of Company C, Battalion of Engineers, serving with the Army of the Potomac until Feb. 16, 1864, and gaining the permanent rank of captain of engineers on July 3, 1863. He was with General Sherman's army in the Atlanta Campaign, receiving the brevet ranks of major, July 22, 1864, and lieutenant colonel, March 13, 1865—both for "gallant and meritorious service."

After the war, Barlow superintended engineering work on coastal fortifications in Florida and New York, and harbor improvements on Lake Champlain. He reached the permanent rank of major of engineers Apr. 30, 1869, when he was assigned to General Sheridan's staff as Chief Engineer of the Military Division of the Missouri, serving in that capacity until July 1874. His field work during that period included several scientific expeditions, his reconnaissance of the Upper Yellowstone in 1871 being the most important. While with a Northern Pacific Railroad surveying party the following year, his escort fought off an attack by a thousand Sioux under Sitting Bull.

From 1874 to 1883 he had charge of fortification and harbor work on Long Island Sound; then on harbor improvement for Lakes Superior and Michigan until 1886, and on the improvement of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, including the building of a ship canal at Muscle Shoals, which was completed Nov. 10, 1890.

From 1891 to 1896, Colonel Barlow (he received the permanent rank of colonel of engineers on May 10, 1895) was the senior commissioner of the International Boundary Commission charged with remarking the boundary with Mexico west of the Rio Grande River, which was followed by engineering work in the Southwest Division.

In 1898, Colonel Barlow was stationed in New York City with charge of improvement work on the Hudson River while serving on a number of important commissions. He was retired with the rank of Brigadier General and Chief of the Corps of Engineers on Apr. 30, 1901.

This tribute was paid him in the Report of the Annual Reunion, June 11, 1915, prepared by the Association of Graduates, USMA, p. 51:

"Modesty and courtesy were the characteristic features of his life. Wise and sincere, brave courteous and altogether loveable, he leaves a memory of Christian manhood which all who knew him will cherish."

Sources: The publication of the Association of Graduates, USMA, cited above, and data provided by Colonel Barlow's daughter in 1963.

COLLINS JACK [JOHN H.] BARONETT. Born in 1827 in Glencoe, Scotland; still living as late as 1901. The rescuer of Truman C. Everts, who was lost from the 1870 Washburn party of Yellowstone explorers and wandered alone for 37 days in the wilderness.

Many of the details of the colorful career of Jack Baronett (better known as "Yellowstone Jack") come from the biographical sketch that Hiram M. Chittenden included in his 1895 edition of The Yellowstone National Park (pp. 291-92). From it we know that he went to sea at an early age, but deserted his ship in China in 1850 in order to go to the gold fields of California. The lure of gold drew him to other strikes in Australia and Africa, and he made a voyage to the Arctic as the second mate on a whaling ship before returning to California in 1855. He served as a courier for Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston during the Mormon War and took part in the Colorado gold rush on the eve of the Civil War.

Baronett's sympathies were with the South, so he joined the First Texas Cavalry. Abandoning the "lost cause" in 1863, he took service briefly with the French under Maximilian in Mexico.

Baronett came to Montana Territory in September of 1864 and his movements afterwards are better known. He was a member of one of the prospecting parties that crossed the Yellowstone plateau that fall and was with the "Yellowstone Expedition" of 1866. He wintered at Fort C. F. Smith and was among those prospectors who made their way through the hostile Sioux to the Gallatin Valley to obtain relief for the nearly starved garrison of that northernmost outpost on the Bozeman road.

Service as a scout with General Custer's expedition to the Black Hills and another foray into the Yellowstone country in 1869 increased Baronett's familiarity with the region. Thus, when Truman C. Everts was lost from the Washburn party in 1870, Baronett was considered best qualified to search for him. As a result, the unfortunate explorer was found in time to save his life.

Immediately after the dramatic rescue of Everts, Baronett built a toll bridge over the Yellowstone River near its junction with the Lamar, and he operated it for many years as a vital link in the road to the mining region on the Clark Fork River. The care of his bridge was often left in other hands as Baronett guided hunting parties, scouted for the military, and continued his search for elusive mineral riches.

One of the men he guided in the park in 1875, Gen. William E. Strong, has left an excellent description of Baronett. He says:

" 'Jack Baronett,' as he is best known, is a celebrated character in this country, and, although famous as an Indian fighter and hunter, he is still more celebrated as a guide... he is highly esteemed by those who know him and his word is as good as gold. He is of medium stature, broad-shouldered, very straight and built like Longfellow's ship, for 'strength and speed.' Eyes black as a panther's and as keen and sharp; complexion quite dark with hair and whiskers almost black. He speaks well, using good English, and his manner is mild, gentle and modest; is proud of his knowledge of the mountains and of his skill with the rifle. I took to him at once . . . . " See "A Trip to the Yellowstone National Park in July, August, and September, 1875" (1876), 43.

While in the Black Hills during the winter of 1876-77, Baronett became involved in a dispute with W. H. Timblin over the recording of mining claims. Fired upon by Timblin, he returned the shots with mortal effect. This event led to the following comment: "As well might the eastern miners walk with shot guns into a gulch lair of Hogback Grizzlies, as to arouse Barronette, the Buchannons and other comrades from the upper Yellowstone." Letter, J. S. Farrar to P. W. Norris, Feb. 26, [1877], in P. W. Norris Collection, Henry E. Huntington Library, Pasadena, Calif.

Despite his service for the Confederacy, Baronett enjoyed the respect and confidence of his former enemies. He was the preferred guide of Gen. Philip H. Sheridan on several junkets through the park and also the only member of the original civilian police force to be retained when the Army took over management of the area in 1886. He thus became the first scout to serve the new administration (he had even been considered for the superintendency, upon the recommendation of the Governor of Montana Territory in 1884).

Baronett married Miss Marion A. Scott, of Emigrant Gulch, at Bozeman, Mont., on Mar. 14, 1884. His wife later held the position of postmistress at Mammoth Hot Springs in the park.

Baronett's 35-year association with the Yellowstone region has been justly recognized by coupling his name to an outstanding peak which flanks the road to the park's northeast entrance, but, otherwise, life did not treat him well. His toll bridge, in which he had invested $15,000, was taken from him in 1894, and he spent $6,000 in lawyer's fees to obtain from Congress a niggardly compensation of $5,000. That money was invested in an expedition to Nome, Alaska, during the last great "gold rush," but his schooner and his hopes were both crushed in the Arctic ice.

Thereafter, the old man's health failed rapidly and he was soon too feeble to earn a living at the rough work available to him. The trail ends at Tacoma, Wash., in late January or early February of 1901, when he was given a ticket by a charitable organization to get him to a friend at Redding, Calif., and it ends with a touch of irony: Six weeks after Baronett's disappearance, he was sought as the only heir of a titled brother killed in the Boer War.

Sources: Hiram M. Chittenden, The Yellowstone National Park (Cincinnati, 1895), pp. 291-2. "Capt. Baronette" in The Livingston (Mont.) Enterprise, Apr. 20. 1901, and the P. W. Norris Papers, Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif.

CHARLES W. COOK. Born in Unity, Maine, in February 1839; died in White Sulphur Springs, Mont., Jan. 30, 1927. A member of the 1869 Folsom party of Yellowstone explorers, and co-author of the first magazine article describing the Yellowstone region.

Charley Cook attended the Quaker Academy at Vassalboro, Maine, with his boyhood friend, David E. Folsom. Together, they went on to the Moses Brown Quaker School at Providence, R.I., where Cook completed his education after David was forced to drop out because of ill-health. From there, the spirit of adventure swept him westward.

Drawn by reports of a rich gold strike near Pikes Peak, Cook made his way to Colorado—only to find there was no fortune awaiting him there. Early in 1864 he joined a band of drovers who were moving 125 head of cattle to Virginia City, a new mining town in what had just become Montana Territory. The eight men were stopped by Sioux and Cheyenne Indians near Green River—where they had to pay a steer for the privilege of passing on with their herd.

The remaining cattle were delivered safely on Sept. 22, 1864, just as the placer mining in Alder Gulch was at the peak of its frantic activity. There being no more ground available, Cook moved on to Last Chance Gulch (present Helena), and then to Confederate Gulch. There he found a job managing the Boulder Ditch Co., which supplied water to the placer mines around Diamond City. One of the men he employed soon after taking over in 1865 was William Peterson. His old chum, David Folsom, joined him there in the fall of 1868.

It was that summer when Cook first thought of visiting the Yellowstone region. An eastern mining man with business around Diamond City (which was then without a hotel) boarded for a time at the headquarters of the ditch company, where he heard some of the rumors then current concerning the wonders lying south of Montana's settlements. Immediately interested, this guest proposed an exploration of the region, but it was already too late to organize a trip there that season. However, the notion persisted with Cook.

When notice of the intention of a party of citizens from Virginia City, Helena, and Bozeman to make just such an exploration appeared in the Helena Weekly Herald of July 29, 1869, Cook and Folsom sought permission to accompany the expedition, and they were greatly disappointed when the project collapsed at the last moment for lack of a military escort. Having already made their preparations for the trip, the two Quakers decided to go anyhow, a resolution in which they were joined by William Peterson.

The party left Diamond City on Sept. 6, 1869, well armed and outfitted, and their trip of 36 days introduced them to the principal features of wonderland. The considerable interest evidenced in the information they brought back induced these explorers to combine their notes in an account suitable for publication in magazine form. The modest, well-written article prepared by Folsom was sent to Cook's mining friend, who had offered to find a publisher; however, attempts to place it with prominent magazines, such as Scribner's and Harper's, were rebuffed. It was finally accepted by the Chicago Western Monthly Magazine, which used the account in a somewhat abbreviated form, and under Cook's name, in the issue of June 1870.

Cook left the Boulder Ditch Co. soon after his return from the Yellowstone adventure, serving briefly as the receiver for a Gallatin Valley flour mill before driving a band of sheep from Oregon to the Smith River Valley in 1871. He developed a large ranch called "Unity" on land he had claimed about 10 miles east of Brewer's Springs (now White Sulphur, Mont.), and it was there that he brought his bride—a Miss Kennicott, of New York—in 1880. They raised three children, one of whom has survived to this writing.

Charles W. Cook outlived his comrades, and he alone was still alive and present at the celebration of Yellowstone Park's 50th anniversary in 1922. The presence of that tall, spare old man with the craggy face and piercing eyes provided a direct link with the park's era of definitive exploration, and he was lionized. But even greater honor came to him before his death. It was in the form of a letter which arrived in February 1924, with this message:

"My Dear Mr. Cook:

Through the courtesy of Mr. Cornelius Hedges, Jr., and of Congressman Scott Leavitt, I have learned that you are within a few days to celebrate your 85th birthday anniversary. As one of the pioneers of the great intermountain West, the first explorer of what is now Yellowstone Park, and one of the men responsible for the founding of the national park system, you have rendered a series of national services of truly notable character. Upon these I wish to extend my felicitations, and my congratulations upon your approaching birthday. I hope you may live to enjoy many more celebrations of the same anniversary."

That kindly tribute was signed by Calvin Coolidge, President of the United States.

Sources: Lew L. Callaway, Early Montana Masons (Billings, Mont., 1951), pp. 29-33, and family records made available by Mrs. Oscar O. Mueller, Lewistown, Mont.

WALTER WASHINGTON DELACY. Born in Petersburg, Va., Feb. 22, 1819; died in Helena, Mont., May 13, 1892. Leader of a party of prospectors who passed through the southwest corner of the Yellowstone region in 1863, and compiler—with David E. Folsom—of the first map (deLacy's 1870 edition) to show most of the prominent features with reasonable accuracy.

He was the son of William and Eliza deLacy of Norfolk, Va. They came of a noble Irish family that had declined on these shores, and young Walter lost both parents while yet a boy. His upbringing was left to a pair of maiden aunts and a bachelor uncle, who did well by him. In fact, his uncle even moved to Emmetsburg, Md., to be nearby while the young man attended Mount Saint Mary's Catholic College (where he specialized in mathematics and languages French, Portuguese, and Spanish).

Since civil engineering was the career he wished to follow, deLacy's uncle obtained for him an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, but that schooling was denied him through official chicanery. The wrong was soon righted personally by Professor Dennis Hart Mahan, who felt a responsibility to the boy's family. He took Walter to West Point for tutoring by himself and other officers, thus providing him with what was undoubtedly the finest education in civil and military engineering available in that day.

In the year 1839, while deLacy was working as a railroad surveyor, he was called to Washington to take an examination for a commission in the regular army. With the rank of lieutenant, the young man became an assistant instructor in French at the Military Academy, but he soon resigned that position to take a similar one with the U.S. Navy. Future officers were then schooled at sea and deLacy taught languages to midshipmen aboard ships until 1846.

Returning to his true interest, engineering, deLacy was employed by a group of wealthy men to search for abandoned Spanish silver mines, and he was in the Southwest when war began with Mexico. He took a brave part in that conflict, gaining a captaincy, and during the years immediately following he was employed in the West on a number of Government projects a survey for a railroad across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, the survey of the 32d parallel from San Diego, Calif., to San Antonio, Tex., and hydrographic surveys on Puget Sound.

The latter work put deLacy in position to play a very important role in the Indian war of 1856 in the struggling new Territory of Washington. Governor Isaac I. Stevens made him engineer officer with responsibility for planning and constructing the blockhouses and forts that protected the settlements while the volunteer troops campaigned in the Indian country east of the Cascade Mountains.

Having proven himself as a military engineer, deLacy was given employment on a favorite project of Governor Stevens—the construction of the Mullan Road. He was the man who set the grade stakes for the crews, and, at the eastern terminus, he later laid out the town of Fort Benton at the head of navigation on the Missouri River.

Apparently deLacy's experience in Mexico gave him faith in the mineral possibilities of Idaho and Montana. He followed the succession of stampedes that opened up the northern Rocky Mountains, and it was a prospecting tour in 1863—with a party he called "the 40 thieves" that took him across the southwestern corner of the present Yellowstone Park. There he saw Shoshone Lake and the Lower Geyser Basin, but failure to publish his discoveries adequately prevented his getting the credit his exploration merited.

But there was a valuable result. In 1864 the first Territorial Legislature of Montana commissioned deLacy to prepare an official map to be used in establishing the counties, and his map, published in 1865, showed just enough of the Yellowstone region to whet the interest of Montanans (on it was the lake and the falls of the Yellowstone River, with a "hot spring valley" at the head of the Madison River). The map was periodically improved during the 24 years it was in print, and a copy of the 1870 edition—complete with the route of the Folsom party of the previous year, and extensively corrected to accord with their observations—was carried by the Washburn party of 1870.

In Montana's Sioux War of 1867, deLacy assumed a familiar role when he was appointed colonel of engineers for the Territorial Volunteers. In that conflict he displayed his usual quiet bravery by going to the relief of Federal troops beleaguered at Fort C. F. Smith on the Bozeman trail. Loading a wagon train with Gallatin Valley potatoes and flour for the famished garrison, he pushed through with a handful of volunteers—despite warnings that the Sioux would gobble them up.

The remaining years of deLacy's life were occupied with surveying and civil engineering. He fixed the initial point and laid out the base line for the public land surveys of Montana, prepared a map for the Northern Pacific Railroad that greatly influenced the choice of a route through the territory, and accomplished a perilous survey of the Salmon River. He was later city engineer for Helena, Mont., and an employee in the office of the Surveyor General there. He worked to within a few weeks of his death.

Source: "Walter Washington deLacy," Contributions to the Historical Society of Montana 2 (1896), pp. 241-251.

GUSTAVUS CHEENY DOANE. Born in Galesburg, Ill., May 29, 1840; died in Bozeman, Mont., May 5, 1892. The officer in command of the military escort that accompanied the Washburn party through the Yellowstone region in 1870. He was also the author of an official report that appeared as a congressional document, thus providing information recognized as reliable.

Doane's parents moved to Oregon Territory by ox-wagon when he was 5 years old, and in 1849 they were lured south to the gold fields of California, so that the lad grew to manhood in the exciting atmosphere of the mushroom camps and towns of the Argonauts. It was that environment, and the University of the Pacific at Santa Clara, that shaped the man.

In 1862, young Doane went east with the "California Hundred," determined to serve the Union cause. Enlisting in the Second Massachusetts Cavalry on October 30, he had advanced from private to sergeant by Mar. 23, 1864, when he was commissioned a first lieutenant of cavalry. He was honorably mustered out of service on Jan. 23, 1865.

For a time after the war, Doane was involved in the military government of Mississippi, holding offices that included that of mayor of Yazoo City. He married a southern girl, Amelia Link, on July 25, 1866, but it was an unhappy union that ended 12 years later when she divorced him at Virginia City, Mont.

Doane returned to military life July 5, 1868, being commissioned a second lieutenant in the Second U.S. Cavalry. His company arrived at Fort Ellis in May 1869 to become part of the garrison of that post established less than 2 years earlier for the protection of the Gallatin Valley in Montana Territory. And so, when a detail was needed to escort the Washburn party of 1870 into the Yellowstone wilderness, there was just the right officer available at the post that was the logical point of departure.

The assignment was routine—"proceed with one sergeant and four privates of Company F, Second Cavalry, to escort the surveyor general of Montana to the falls and lakes of the Yellowstone, and return"; but Lieutenant Doane made a better-than-routine report upon his visit. That remarkably thorough description was the first official information on the Yellowstone region and its unusual features, and it was characterized by Dr. F. V. Hayden, U.S. Geologist, in these words: "I venture to state, as my opinion, that for graphic description and thrilling interest it has not been surpassed by any official report made to our government since the times of Lewis and Clark."

Great interest was created by that report, and as a result, Doane was often referred to as "the man who invented wonderland." He was described as of splendid physique, standing 6 feet 2 inches, straight as an arrow, and swarthy, with black hair and a dark handlebar mustache. He was 200 pounds, "tall, dark and handsome," and endowed with a loud voice and an air of utter fearlessness. Add to that all the competence of a natural frontiersman, including superb horsemanship and deadly proficiency with a rifle, and there stands the man of whom a soldier once said, "We welcomed duty with the lieutenant." There is also praise of the finest type in the published memoir of Maj. Gen. Hugh L. Scott, one of Doane's shavetails who made it all the way to chief of staff; he looked back over the years and said of that adventurous officer he had served under, "I modeled myself on him as a soldier."

Being a restless, energetic, intelligent man with great powers of endurance, Doane was always busy. He was in demand to escort official parties through the Yellowstone region—as he did the Barlow-Heap and Hayden Survey parties in 1871, and the grand excursion of Secretary of War William W. Belknap in 1875—and when not so employed he volunteered to lead scouting parties and developed a force of Crow Indian auxiliaries of considerable value during the Nez Perce Campaign of 1877 (a war which was a disappointment to Doane because his orders kept him out of the real action).

Late in 1876, Lieutenant Doane was sent on one of the most unusual and bizarre expeditions ever fielded by our army in the West. It was nothing less than a winter exploration of the Snake River from its Yellowstone headwaters to the junction with the mighty Columbia—a task to be accomplished with a detail of six men and a homemade boat. It was his good fortune to lose the boat—but not his men—in the Grand Canyon of Snake River, thus ending in an early disappointment a venture which could only have matured into tragedy.

On Dec. 16, 1878, Doane married his second wife, Mary Hunter, daughter of the old pioneer who was the proprietor of Hunter's Hot Springs on the Yellowstone River at present Springdale, Mont. After a honeymoon in the "States," where Lieutenant Doane had a winter assignment, the couple returned to Montana and life at Fort Ellis.

In 1880, Doane was involved in what promised to be the grandest adventure of his life, one that might have taken his life had he not refused to go through with it. He was ordered East to be considered for duty in the Arctic—as the commander of a party which was to implement the "Howgate Plan" for the study of Arctic weather and living conditions. For its part, the U.S. Army was to establish and maintain a station at Lady Franklin Bay on Ellesmere Island, less than 500 miles from the North Pole. Doane sailed north on the Proteus, a leaky and inadequate vessel that was unable to reach its destination (and almost failed to get back). The experience was enough for Doane and he declined the duty, letting it go to a young Signal Corps officer named A. W. Greely.

A promotion to the rank of captain came to Doane Sept. 22, 1884, and his subsequent service was mainly on the Pacific Coast and in the Southwest. While doing monotonous duty at dusty outposts, he dreamed of explorations in Africa, and he made serious tries for the superintendency of Yellowstone National Park in 1889 and 1891.

But Doane's days were numbered. His health began to fail under the hard field duty required of him in Arizona, and he reluctantly asked for retirement. It was not allowed him because he had neither the age (64 years) or the service (40 years) required at that time, and all that could he done was to allow him 6 months leave. He returned to his home as Bozeman, Mont., but contracted pneumonia and died there.

Sources: Hiram M. Chittenden, The Yellowstone National Park, (Cincinnati, 1895), pp. 293-95; Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States Army 1 (Washington, 1903), p. 375, and various newspaper items from the Montana press.

TRUMAN C. EVERTS. Born in Burlington, Vt., in the year 1816, died in Hyattsville, Md., Feb. 16, 1901. A member of the 1870 Washburn party of Yellowstone explorers, whose loss in the wilderness and subsequent rescue after 37 days heightened public interest in the expedition; also, author of a timely article in Scribner's Monthly a year later, when the movement to create Yellowstone Park was taking form.

Helpful as that account was in creating an awareness of the Yellowstone region and what it contained, just as a group of determined men were opening that campaign which eventually led to creation of a Yellowstone National Park, it provided very little personal information about the man who survived such incredible hardships, and nearly his entire life before and after the Yellowstone adventure remained obscure until August 1961 when his son walked into park headquarters at Mammoth Hot Springs with some facts.

Thus, we now know that Truman C. Everts was one of a family of six boys. His father was a ship captain and the lad accompanied him as cabin boy during several voyages on the Great Lakes. It is unlikely that he received anything more than a public school education, though nothing is certainly known of his life before the age of 48 except that he had been married.

On July 15, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln appointed Truman Everts so be Assessor of Internal Revenue for Montana Territory, an indication he had been a staunch supporter of the Republican party. Yet he was unable to weather the political intrigues of the Grant administration and lost his patronage position on Feb. 16, 1870. Everts lingered in Montana for a time, in the hope of obtaining something else, but by mid-summer he had decided to return to the East with his grown daughter, Elizabeth, or "Bessie," who was his housekeeper and also the belle of Helena society. An entry in the diary of Cornelius Hedges shows the purchase of household effects auctioned by Everts on July 6, in preparation for the move.

Everts' accompaniment of the Washburn party into the Yellowstone wilderness was in the nature of a between-jobs vacation—though it turned out somewhat differently. The details of his travail are available in his "Thirty-Seven Days of Peril" (in Scribner's Monthly for November 1871). He was rescued at the last possible moment by "Yellowstone Jack" Baronett and George A. Pritchett. While the one nourished the feeble spark of life remaining in a body wasted to a mere 50 pounds, the other went 75 miles for help, so that the lost man undoubtedly owed his life to those hardy frontiersmen who had set aside their usual pursuits to succor him.

It would seem that Everts' gratitude would know no limits; yet, it did not even extend to the payment of that reward his friends had offered for his rescue, he maintaining he could have made his own way out of the mountains. Unfortunately, there was more to his ingratitude than that. When Baronett called on Everts several years later in the course of a visit to New York, he was received so coldly that he afterward said "he wished he had let the son-of-a-gun roam."

Following the passage of the Yellowstone Park act, there was a strong sentiment for making Everts superintendent of the area. However, he was reluctant to accept the position without some provision for a salary, and, before that was resolved, he became a delegate to the Liberal Republican convention at Cincinnati. By thus joining Horace Greeley's attempt to split the party, he passed beyond the pale of orthodoxy and was given no further consideration.

The Bozeman, Mont., Avant Courier of May 9, 1873, indicated that Everts had just returned to that town after securing a part interest in the post trader's store at Fort Ellis; but he did not remain there, despite the statement that he "will be permanently located among us."

In 1880 or 1881, Truman C. Everts married a girl who was said to have been 14 years old at the time, and they settled on a small farm at Hyattsville, Md., which was then on the outskirts of Washington, D.C., but has since been absorbed in its urban sprawl. The couple had a child—Truman C. Everts, Jr.—born Sept. 10, 1891, when the father was 75 years old. This son understood that his father was a minor employee of the Post Office Department in his declining years, and that the family went through some very hard times during the Cleveland administration, when his politics were of the wrong persuasion.

Sources: Nathaniel P. Langford, The Discovery of Yellowstone National Park (St. Paul, Minn. 1905), p. xviii, and an interview with Truman C. Everts, Jr., in Yellowstone National Park, Aug. 11, 1961.

DAVID E. FOLSOM. Born in Epping, N.H., in May 1839; died in Palo Alto, Calif., May 18, 1918. A member of the 1869 Folsom party of Yellowstone explorers, coauthor of the first magazine article descriptive of the Yellowstone region, and proponent of a suggestion (the second such known to have been made) for reservation of the area and its wonders in the public interest.

Since his was a Quaker family, Dave Folsom was sent to the academy at Vassalboro, Maine, with his boyhood friend, Charles W. Cook, and they both went on to the Moses Brown Quaker School at Providence, R.I. It was there, while he was preparing for a career as a civil engineer, that Folsom's health broke down, so, following his physician's recommendation, he started for the West.

The gold mines of Idaho beckoned young men in 1862, and Folsom was proceeding in that direction when he heard that the Fisk party was organizing at Fort Abercrombie, on the Red River of the North, for the purpose of pioneering a northern route to the mines. Reaching the rendezvous with the same Minnesota contingent that included Nathaniel P. Langford, Folsom was accepted as a herder for the train of 52 wagons that departed with its escort of soldiers in midsummer.

The ineptness of the man detailed to supply wild meat for the 130 men, women, and children of the wagon train led Folsom to volunteer his services as hunter for the party. Earlier hunting in Maine had made him a good woodsman and an excellent shot, so he had no difficulty keeping the expedisioners well supplied as they journeyed across Minnesota and the Territory of Dakota to Fort Benton, and then along the Mullan Road toward Washington Territory (which then abutted on Dakota along the Continental Divide).

As the Fisk party was about to cross the Rocky Mountains, word was received that the diggings on Salmon River, which had been their objective, were "played out", so many of its members turned to a new strike on Grasshopper Creek, where a town called Bannock had already appeared. Folsom spent the winter of 1862-63 there, then moved on to Virginia City and a chancy altercation with outlaw George Ives. The latter's attempt to provoke Folsom into an unfair fight was met in a manner as unexpected as it was untypical of his Quaker background—he floored the bad man with a flung pool ball! It was a rash act, from which Folsom escaped with his life only because friends got him out of town until the work of the vigilantes was completed.

Soon becoming discouraged with placer mining, Folsom took employment on the ranch of Henry C. Harrison at Willow Creek, in Madison County, before settling on land in that vicinity. In addition to the ordinary vicissitudes of pioneer ranching, life there was an unending struggle against inroads of ferocious grizzly bears. Four years of that was enough to turn him briefly to surveying for a livelihood before he joined his old friend, Charley Cook, in the operation of the ditch company at Confederate Gulch in the winter of 1868-69. This employment led him into the Yellowstone wilderness with Cook and Peterson, in what was the first step in the definitive exploration of the area now included in Yellowstone National Park.

Following that adventurous trip, Folsom went to work in the office of the Surveyor General of Montana Territory, at Helena. As a result of this association, he was able to furnish Henry D. Washburn with much information about the Yellowstone region and its "wonders" (also advancing a suggestion that the area should be reserved for public use), and he collaborated with Walter W. deLacy in the revision of the latter's Map of the Territory of Montana, With Portions of the Adjoining Territories, so that the Yellowstone region was at last delineated with reasonable accuracy. A copy of this 1870 edition of deLacy's map was carried by the Washburn party of explorers.

Folsom formed a partnership with deLacy and they engaged in land surveying until 1873. Returning to New Hampshire in that year, Folsom remained there until his marriage to Miss Lucy Jones in 1880. The couple settled in Montana, developing a large sheep ranch on Smith River, near the Cook homestead.

Following his return to Montana, Folsom was also prominent in public life. He served as the treasurer of Meagher County from 1885 to 1890, and he was a State senator in the third and fourth sessions of the Legislative Assembly (actually president pro tem of the Senate during the fourth). He was an appointed member of the commission that supervised the construction of the State Capitol at Helena, and in 1900 he ran for the governorship of Montana but was defeated.

The Folsoms moved to California when their son, David, Jr., enrolled at Stanford University. The young man was assistant professor of mining engineering there at the time of his father's death.

Source: Lew L. Callaway, Early Montana Masons (Billings, Mont. 1951), pp. 29-33.

WARREN CALEB GILLETTE. Born in Orleans, N.Y., Mar. 10, 1832; died in Helena, Mont., Sept. 8, 1912. A member of the 1870 Washburn party of Yellowstone explorers, and the leader of the group that remained behind to make a last, desperate search for the lost Truman C. Everts.

Warren was the eldest of five children raised by parents of French Huguenos origin. Upon completing public school he entered Oberlin College, in Ohio, and studied there into his 18th year before succumbing to that restlessness that eventually took him to Montana.

After stopping for a time in Columbus, Ohio, Gillette returned to New York State where he worked as a clerk in Oneida County until 1855. He then removed to Chicago, working for E. R. King & Co., wholesale hatters and furriers, until 1859. On the basis of that experience he opened a retail store at Galena, Ill., but abandoned the business after 2 years. Returning once more to his home State, he worked at the manufacturing of furs in New York City until the spring of 1862, when word of the discovery of gold in Idaho reached the East.

Lured by the prospect of sudden wealth, Gillette made his way westward. As St. Louis he boarded the steamer Shreveport, intending to go by the Missouri River route to Fort Benton landing, and from there overland to the Salmon River mines. But low water stopped the vessel between Fort Buford and the mouth of Milk River, so that its passengers and freight were put ashore short of their Montana destination.

The emigrant party Gillette was with had brought wagons and teams with them, and their journey was continued overland toward Fort Benton. Two days later they met Indians, some of whom were inclined to turn them back. While the Indians were holding a council to decide the matter, the emigrants turned about with the intention of avoiding trouble by voluntarily returning to the Missouri River. But the Indians then informed them they could not go back, but must go on to Fort Benton, which they were glad to do.

By the time this party reached Montana City on Little Prickly Pear Creek it was rumored that gold had been discovered on Grasshopper Creek. While most of the party rested there in "Camp Indecision," a delegation was set to look over the new strike. However, Gillette went on to Deer Lodge (then "La Barge City") where he purchased a cabin with the intention of opening a store.

But the word that came back from Grasshopper Creek was so encouraging that Gillette moved there in December of 1862, becoming a pioneer merchant in the developing town of Bannack. He brought his goods—an assortment of miner's supplies—directly from Fort Benton by packhorse, gaining valuable experience in freighting and the ways of horsethieves while so employed.

The store was moved to the new town of Virginia City after gold was discovered in Alder Gulch in 1863. It was there that Gillette became associated with James King in a partnership that lasted until 1877. With the opening of Last Chance Gulch, King and Gillette moved their stock from Virginia City to Helena, remaining in the freighting and merchandising business there until 1869. After that time the partners engaged in mining operations, particularly in the development of the Diamond City placer mines.

A project undertaken very early by King and Gillette showed their foresight and ingenuity. All travel between Fort Benton and Helena avoided the impassable Little Prickly Pear Canyon by using a difficult road over Medicine Rock and Lion Mountains, but the partners decided it would be to their advantage to build a toll road through the 10-mile canyon. The equipment available for the work was two plows, which cost them $175 apiece, picks, shovels, and blasting powder, and with such means the road was completed in 1866 at a cost of $40,000. Tolls returned that amount within 2 years and the road remained a profitable enterprise to the expiration of the charter in 1875.

At the time of the Yellowstone expedition, Gillette was considered the best woodsman of the party, and his willingness to remain behind in the wilderness, with two soldiers, to continue the search for the lost Truman Everts was a generous act of a man whose humanity was expressed thus in his diary: "I hated to leave for home, while there was a chance of finding poor Everts . . . is he alive? is he dead? in the mountains wandering, he knows not whither?" It was an unsuccessful search, but not for lack of diligence.

After 1877, Gillette turned to State politics and to sheepraising. He served four times in the Legislative Assembly of Montana Territory, twice on its Legislative Council, and was a member of the convention that framed the constitution for statehood. His 12,000-acre ranch near Craig, in Deer Lodge County, carried 20,000 head of Merino sheep and he did much to popularize that breed.

Gillette never married: a spinster sister, Eliza, was his housekeeper and companion until her death in 1897.

Sources: A. W. Bowen & Co., Progressive Men of the State of Montana (Chicago, c. 1902) pp. 177-78; M. A. Leeson, ed., History of Montana, 1739-1885, (Chicago, 1885), p. 1214, and the obituary file, Montana Historical Society, Helena.

SAMUEL THOMAS HAUSER. Born in Falmouth, Ky., Jan. 10, 1833; died in Helena, Mont., Nov. 10, 1914. A member of the 1870 Washburn party of Yellowstone explorers.

A basic education in the public schools of his native State was improved by the careful tutoring of his cousin, Henry Hill, who was a Yale graduate. In that manner, he gained the qualifications for his first employment.

In 1854, Hauser went to Missouri, where he progressed from a railroad surveyor to an assistant engineer on the construction of the Missouri Pacific Railroad. On the eve of the Civil War, though but 28 years old, he was chief engineer on the Lexington branch of that line.

There in Missouri, in that last year before hostilities, Hauser was involved in a local event that changed his life entirely. He heard that a man was to be tried for his life by a Justice of the Peace of a nearby settlement, and, being skeptical of the legality of such a procedure, he rode over with a friend to see what was going on. They found that a young man stood accused of poisoning a spring, a charge that the "court" sustained without a show of evidence. The trial had been held merely to condemn the man, and with that done a rope was instantly produced for his hanging. At that point Hauser, who was on horseback at the edge of the crowd, made an objection. The onlookers reacted so violently to that interference with their judicial proceedings that only the quick action of his friend saved Hauser from being shot off his horse. The condemned was hanged, and the obvious unfairness of the trial so angered Hauser that he commented on it in the Booneville newspaper (published by George Graham Vest, later U.S. Senator and defender of Yellowstone National Park). As a result, the meddling railroader was warned to leave those parts.

News of the finding of gold in Idaho reached the East at that time and Hauser decided to try his luck there. He boarded a Missouri River steamer which landed him at Fort Benton in June 1862. He went overland to the Salmon River placers, prospected for a time and then moved to Grasshopper Creek that fall. A season in the town of Bannack that developed there convinced Hauser he would have to look elsewhere for his fortune, so he joined James Stuart's "Yellowstone Expedition" of 1863. This exploration of the country along the lower Yellowstone River found no gold, but it did run into hostile Indians whose night attack on the party came near finishing Hauser. In the course of that melee he was struck in the chest by a ball that penetrated a thick notebook he was fortunately carrying, then came to rest on a rib over his heart.

In 1865, N. P. Langford assisted Hauser and William F. Sanders to establish a bank at Virginia City, Montana Territory, under the firm name of S. T. Hauser & Co. Hauser soon after organized a mining company and built the first smelter in the territory at Argensa, and the following year he organized the First National Bank of Helena and the St. Louis Mining Co. at Phillipsburg. His later activities included establishment of banks at Missoula, Butte, Fort Benton, and Bozeman, the building of six branch railways and interest in numerous mining and smelting enterprises.

While in the Yellowstone region with the Washburn party, Hauser used his engineering skill to good purpose on several occasions by measuring the heights of waterfalls and an eruption of the Beehive Geyser, and sketch-mapping Yellowstone Lake. He also kept a messy but revealing diary of much of the trip.

Hauser was always a Democrat in his politics. He was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 1884, and was appointed Governor of Montana Territory by President Grover Cleveland in June 1885. He was the first Montana resident to be named Governor, serving 18 months in that capacity.

Samuel Thomas Hauser married Miss Helen Farrar, the daughter of a St. Louis physician, in 1871, and they had two children.

Sources: A. W. Bowen & Co., Progressive Men of the State of Montana (Chicago, c. 1902), pp. 202-03, and the obituary file, Montana Historical Society, Helena.

FERDINAND VANDIVEER HAYDEN. Born in Westfield, Mass., Sept. 7, 1829; died in Philadelphia, Pa., Dec. 22, 1887. The U.S. Geologist and head of the Geological Survey of the Territories (Hayden Survey), which made the first official investigation of the Yellowstone region in 1871.

Hayden's boyhood was brief. His father died when he was 10 and he went to live with an uncle in Ohio. There, he began teaching in country schools at the age of 16 and entered Oberlin College 2 years later. Following graduation in 1850, he studied at the Albany Medical School in New York, where he also obtained a sound education in paleontology and geology while earning his medical degree. The diploma proved less important to Hayden than his introduction to the sciences.

Upon leaving medical school in 1853 he was induced to spend a summer collecting tertiary and cretaceous fossils in the White River Badlands near Fort Pierre, Dakota Territory. That adventuring turned Hayden's interest irrevocably toward geology. With financing supplied by individuals, organizations, and the Federal Government, he continued his field work which was his apprenticeship as a scientific explorer.

The Civil War years were passed as a surgeon in the Union Army, from which he was mustered out in 1865 with the rank of brevet lieutenant colonel. Immediately following that conflict Hayden was elected a professor of mineralogy and geology in the medical department of the University of Pennsylvania, but that wedding of his two fields of interest did not last.

Hayden was able to obtain $5,000 of unexpended Federal funds in 1867 for use in conducting a geological survey of the new State of Nebraska. That modest budget launched the Hayden Survey, which was thereafter financed by a combination of appropriated funds and contributions from private sources. When his fledgling organization came under the control of the Secretary of the Interior in 1869, it also received a formal title, becoming "The U.S. Geological Survey of the Territories."

The Washburn expedition of 1870 created a public interest in the Yellowstone region, and Hayden—who had come so close to penetrating its mysteries while a geologist with the Raynolds expedition in 1860—capitalized upon that interest by persuading the Congress to grant him $40,000 for a scientific investigation of its features. The work of the Hayden Survey during the summer of 1871 established a basis of facts that was undoubtedly of crucial importance in obtaining passage of the act that created Yellowstone National Park. But, as certainly, there would have been no legislation without Hayden's persistent efforts on its behalf during the winter of 1871-72.

The Hayden Survey accomplished important work in Yellowstone Park and the surrounding area in 1872 and 1878, before its merger with the surveys of King and Powell to form the U.S. Geological Survey (1879). It has been claimed that Hayden "worked so rapidly and published so quickly that shoddiness became the hallmark of his reports"; yet, overall, he was essentially correct in his geological interpretation of a staggering extent of the unknown West.

Dr. Hayden, who held LL.D. degrees from the Universities of Rochester and Pennsylvania, was a member of 17 scientific societies in this country and also a corresponding member of 70 foreign societies. His published titles exceeded 158 at the time of his retirement from the U.S. Geological Survey in 1886 because of failing health. He died the following year—a man described by historian Chittenden as "intensely nervous, frequently impulsive, but ever generous . . . his honesty and integrity undoubted." Time has proven him a man whose work for his Government, and for science, was a labor of love.

Sources; John Wesley Powell, "Ferdinand V. Hayden," in Ninth Annual Report of the United States Geological Survey to the Secretary of the Interior, 1887-88 (Washington, 1889), pp. 31-38, and Charles A. White, "Memoir of Ferdinand Vandiveer Hayden, 1829-87," in Biographical Memoirs of the National Academy of Science 3 (Washington, 1893), pp. 395-413.

DAVID PORTER HEAP. Born in San Stefano, Turkey, in March 1843; died in Pasadena, Calif., Oct. 25, 1910. An army engineer officer attached to the 1871 Barlow party of Yellowstone explorers and co-author of the resulting official report.

The son of the U.S. Minister to Turkey, his basic education was obtained at the Germantown Academy, Pennsylvania, and Georgetown College. He entered the U.S. Military Academy in 1860 and graduated seventh in the class of 1864. He was immediately promoted to first lieutenant, Corps of Engineers, and assigned to the Engineer Battalion of the Army of the Potomac, with which he served for the remainder of the Civil War. He was breveted a captain on Apr. 2, 1865, for gallant and meritorious services during the siege of Petersburg, Va.

After the war he was employed in harbor improvement work on Lake Michigan, and in other engineering work, until February 1870, when he became chief engineer of the Department of Dakota. Thus, his immediate superior was Maj. John W. Barlow, whom he accompanied on a reconnaissance of the Upper Yellowstone in 1871.

Captain Heap returned to his headquarters at St. Paul with the topographic notes, which were thus saved from destruction in the great Chicago fire which consumed Barlow's specimens and photographs, and he was able to produce from them the first map of the Yellowstone region based on adequate instrumental observations.

From March 1875 to May 1877, Heap was in charge of preparations for the participation of the Corps of Engineers in the International Centennial Exhibition, and he represented the United States in 1881 at the International Electrical Exhibition held at Paris, France. He was later engineer of various lighthouse districts, secretary of the Lighthouse Board, and a member of several boards concerned with improvement of rivers and harbors. He retired with the rank of brigadier general on Feb. 16, 1905, after 40 years of service.

Source: Report of the Annual Reunion, June 12th, 1911, prepared by the Association of Graduates, USMA, pp. 89-90.

CORNELIUS HEDGES. Born in Westfield, Mass., Oct. 28, 1831; died in Helena, Mont., Apr. 29, 1907. A member of the 1870 Washburn party of Yellowstone explorers, proponent of the idea of reserving the Yellowstone region in the public interest (this was the third expression of the idea), and special correspondent for the Helena Herald.

Hedges received his elementary education in the village school and the academy in his hometown of Westfield, in the Woronoco Valley of Massachusetts. As was the custom of the time, he attended classes mainly in the winter and spent the growing seasons working on his father's acres. The family home was on Broad Street and it was the boy's daily chore to take the slow-moving oxen along "William's driving way" to the fields on the north side of Great River, where he labored with his father. The hard-working, thrifty conservatism of the land he came from is well illustrated in the manner of Hedges' going-away to college. The day before his departure to begin his schooling at Yale, he cradled a field of buckwheat.

Upon graduating in 1853, Hedges taught school at the academy at Euston, Conn., and also "read law" in a local office, as the prevailing practice of studying under an established lawyer was called. After a year of that double duty he entered the Harvard Law School and was graduated in 1855. That same year he was admitted to the practice of law in the courts of Massachusetts on the motion of Benjamin F. Butler.

On July 7, 1856, Hedges married Edna Layette Smith of Southington, Conn. After another period of schoolteaching, the young couple moved to Independence, Iowa, where he opened a law office and assisted in editing a newspaper. From the latter experience Hedges gained a liking for printer's ink that lasted a lifetime.

In 1864, Hedges moved his family back to Connecticut and struck out for the gold fields of Montana. He walked from Independence, Iowa, to Virginia City, Mont., hunting along the route of the slow-moving wagon train. He worked several claims with the usual miner's luck before moving on to a new camp where the town of Helena soon came into existence. There, he made the acquaintance of the local sheriff, who turned some legal business his way. That allowed him to establish a law office and bring his family out to Montana Territory in 1865.

Hedges was a peaceful man who managed to live in that turbulent environment without becoming involved in its violent happenings—except once. He was a staunch Union man, and though the Territory of Montana had been all but taken over by that Southern element that went West to escape the Civil War (known collectively as the "left wing of General Price's army"), he had decided, along with a few men of like sentiments, to show the colors. The town's loyal women sewed a flag, which was run up the day word of General Lee's surrender was received. The Secessionist element swore they would rip the flag down, so Hedges sat all that first night at his office window, rifle in hand, to prevent it. Fortunately, no attempt was made.

By 1870, Hedges was active in Masonic affairs, an elder in the Presbyterian Church, had established a public library, and was an editorial writer for the Helena Herald. He was coming along, but life was not yet easy. His diary indicates that the Yellowstone trip cost him $280, and that he was uneasy about the expense.

It has been stated that the national park idea was a direct outgrowth of a suggestion made by Cornelius Hedges beside a campfire at Madison Junction on the evening of Sept. 19, 1870. There is no reason to doubt that he advanced a proposal for the reservation of the area the Washburn party had just passed through, so that it would be held for the public good rather than for private aggrandizement. In that, however, he was only restating a proposal he had heard Acting Territorial Governor Thomas Francis Meagher make in October 1865. Undoubtedly, Hedges' comrades recognized his proposal as a restatement of an idea that had surfaced twice before (David E. Folsom of the 1869 expedition made a similar suggestion to Washburn prior to the departure of the 1870 party); thus, Hedges' contribution lay not in a novel suggestion, but in that series of fine articles, so descriptive of the Yellowstone region, which he contributed to the Helena Herald on his return. He was a reporter, and it speaks well for his basic honesty that he never personally claimed to have originated the idea—only that "I first suggested the uniting of all our efforts to get it made a National Park, little dreaming that such a thing were possible."

Following his return from the Yellowstone trip, Hedges continued in the quiet, constructive way of life so typical of him. President Grant commissioned him U.S. Attorney for Montana Territory on Mar. 3, 1871, and he became active in the Montana Historical Society in 1873 (serving as recording secretary from 1875 to 1885). He was Superintendent of Public Instruction for Montana from Jan. 27, 1872, to Jan. 15, 1878, and again from Feb. 22, 1883, to Mar. 17, 1885, most of that time having judicial duties also. Hedges was probate judge of the court at Helena from 1875 to 1880, and from 1880 to 1887 he was the Supreme Court reporter.

In 1884, Hedges was a member of the Constitutional Convention for statehood, and in 1889 he became the first Montanan elected to the State Senate from Lewis and Clark County. His late years were spent almost entirely in the service of the Masonic Order, in which he held high and influential offices.

Upon his death, the Helena Daily Record had this to say of him: "Thoughtful, kind, charitable, ever ready to heed the call of the unfortunate, without selfishness or guile, no better man has ever lived in Montana, nor to any is there a higher mead of praise for what he did and gave to Montana."

Sources: Lew L. Callaway Early Montana Masons (Billings, 1951), pp. 10-12; A. W. Bowen & Co., Progressive Men of the State of Montana (Chicago, c. 1902), pp. 1-2; and the obituary file, Montana State Historical Society, Helena.

NATHANIEL PITT LANGFORD. Born in Oneida County, N.Y., Aug. 9, 1832; died in St. Paul, Minn., Oct. 18, 1909. A member of the 1870 Washburn party of Yellowstone explorers, author of a book on the expedition and one of the group that worked for establishment of Yellowstone National Park.

As the 11th of 13 children born to George and Chloe (Sweeting) Langford, his formal education was limited to what was available at a rural district school, where the schooling was fitted into the slack season between fall harvesting and spring plowing. Though his youth included more farming than schooling, he developed into a well-informed young man—probably one of the advantages of having many older sisters.

Langford remained at home until after the death of his father in 1853, when he removed to St. Paul, Minn., and entered the banking business (he already had 2 years experience as a clerk in the Oneida Bank of Utica). He stayed in St. Paul until 1862, and in June of that year he joined an expedition bound for the Idaho gold fields under the guidance of James L. Fisk.

The overland trip, accomplished by following a route north of the Missouri River, required 3 months, during which the party had many adventures. Arriving first at Gold Creek in Deer Lodge County, they went next to Bannack after the discovery of gold there. In 1863, Langford moved to yet another strike—at Alder Gulch—and he was present when the first building was erected at Virginia City. He returned to the East that year and enroute his party had a narrow escape from the desperados of Plummer's gang.

Two months after the establishment of the Territory of Montana, Langford was commissioned Collector of Internal Revenue on July 15, 1864. He held the position until 1868, when he was removed by President Andrew Johnson, but reinstated by the Senate. Almost before the tumult had died down, Langford resigned his position of collector on the understanding that Johnson would appoint him to the governorship of Montana. However, the Senate, having fought to secure one position for him, refused to confirm another, so Langford was out of a job.

The year following his visit to the Yellowstone region Langford lectured in the East and worked for reservation of its wonders for the public benefit. After a national park was established, he became its first superintendent, holding that position from May 10, 1872, until Apr. 18, 1877, when he was replaced by Philetus W. Norris. The first superintendency was a sterile period during which the park was neither developed nor protected; indeed, one man, without appropriated funds and already fully employed as U.S. Bank Examiner for the Territories and Pacific Coast States, could hardly have been expected to do more than he did—make three brief visits to the area and prepare one report.

Langford married Emma Wheaton, the daughter of a St. Paul physician, Nov. 1, 1876, but his bride died soon after. Eight years later, he married again—to Clara Wheaton, sister of his first wife. After 1885, his life centered in St. Paul, where he engaged in the insurance business and, beginning in 1897, served as president of the Ramsey County Board of Control, handling city and county relief matters until his death from injuries received in a fall.

Sources: Olin D. Wheeler, "Nathaniel Pitt Langford," in Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society 15 (1912), pp. 631-68; A. W. Orton, "Some Scattered Thoughts On The Early Life of N. P. Langford," an unpublished manuscript in the Yellowstone Park Reference Library (1966); and the Langford Papers in the manuscript collection of the Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul.

WILLIAM LEIPLER. Born in Baden, Germany, in 1845. He was a private of the military escort that accompanied the Washburn party through the Yellowstone region in 1870, and the only casualty on that expedition (he was kicked by Stickney's horse on the return). He evidently was made a sergeant immediately upon the return to Fort Ellis, for that was his grade when he volunteered to go with the party that brought Truman C. Everts back to civilization after his rescue.

Leipler was a pianoforte maker before he enlisted in Company B, 20th Regimens of New York Cavalry, on Nov. 23, 1863. Following his discharge from active service at the end of the Civil War, he was unable to adjust to civilian life and enlisted in Company F, Second Cavalry, on Dec. 7, 1866, becoming the most typical of "old soldiers." Described then as being 5 feet, 8-1/2 inches in height, light-haired, and of a florid complexion, he served with the same cavalry outfit—fighting in the Piegan Campaign, the Sioux Campaign (at Lame Deer, Muddy Creek, and Baker's battle on the Yellowstone River), and in the Nez Perce Campaign—until Aug. 5, 1893, when his request for retirement was approved by Gen. Nelson A. Miles. His retirement address was Roos Alley, Buffalo, N.Y. See The National Archives, RG-94, AGO—Enlistment papers, and carded Service Record, Doc. File 13699 PRD-1893.

GEORGE W. McCONNELL. Born in Adams County, Ind., in 1848. He was a private of the military escort that accompanied the Washburn party through the Yellowstone region in 1870, serving as Lieutenant Doane's orderly on the expedition.

At the time of his enlistment he was 5 ft, 6 inches in height, with grey eyes, brown hair, and a fair complexion. He had been a farmer and evidently was satisfied with one hitch in the army. See The National Archives, RG-94, AGO—Enlistment papers.

CHARLES MOORE. Born in Canada in 1846; died Feb. 17, 1921. Though only a private of the military escort that accompanied the Washburn party through the Yellowstone region in 1870, he is noteworthy for having made the earliest pictorial representations of Yellowstone features—those pencil sketches at Tower Fall and as the great falls of the Yellowstone River of which historian Chittenden has said: "His quaint sketches of the falls forcibly remind one of the original picture of Niagara, made by Father Hennepin in 1697."

Moore's enlistment papers show him to have been 5 feet, 5-1/2 inches in height, blue-eyed, dark-haired, and of a ruddy complexion when he enlisted at Cincinnati, Ohio, on November 7, 1868. He served only one hitch with the cavalry, his reenlistment in 1874 being with the Battalion of Engineers; and it was from Company B of that organization that he retired as a sergeant on May 11, 1891. See The National Archives, RG-94, AGO—Enlistment papers.

WILLIAM PETERSON. Born on one of the Bornholm Islands of Denmark, Dec. 3, 1834; died in Salmon, Idaho, Nov. 28, 1919. A member of the 1869 Folsom party of Yellowstone explorers.

Peterson was raised as a farm boy, yet he finished the schooling required under Danish law before he was 15—and also developed an adventurous turn of mind out of keeping with that environment. One day he met a sea captain in the town of Ruma and was bold enough to ask for a place as cabin boy on the man's ship. It was arranged, and that trading voyage to Iceland for tallow, wool, eiderdown, and furs was the beginning of a sea-faring life in which Peterson saw much of the world and advanced himself as far as second mate.

But a seaman's life was also a hard life, and, after 11 years, Peterson decided to try California instead. Being a sailor, he went to his promised land in typical sailor-fashion—by signing on at New York as a hand "before the mast" on the Mary Robinson, which was 120 days making San Francisco by way of the Horn. A gold strike in Idaho was the exciting news in California's great port at that time, so he continued up the coast to Portland, Oreg., then a small town with very muddy streets, from which he ascended the Columbia by river boat to The Dalles.

Peterson reached Elk City early in the summer of 1861 with a partner he had picked up on the boat. Leaving his partner to work their claim, he made a prospecting excursion nearly to the head of Clearwater River, only to find, on his return from that wild region, that the partner had "struck it rich" on their claim while he was away, had sold out for several thousand dollars, and had left the country without dividing with him. Though left destitute, Peterson stayed on, working for wages, running a pack train, and serving as watchman for idle mining properties.

Those years of following one "excitement" after another were long on experience but short on profit, and so, when Peterson moved across the Continental Divide into Montana in 1865, he looked for a less chancy occupation and found it with the Boulder Ditch Co. at Diamond City, in Confederate Gulch. Thus, at the time of his Yellowstone trip in 1869 he was an old employee of the concern managed by Charley Cook.

Each member of the party had particular skills to contribute, and Peterson's were a sailor's expertise with cloth and cordage, a packer's mastery of the diamond hitch, and the all-around caginess of a man who had survived most of a decade in the rough-and-tumble of the mining frontier. He was also an ideal companion, with just the right mixture of common sense and good humor.

Following the return of the best-managed expedition that ever passed through the Yellowstone wilderness, Peterson continued to work for the Boulder Ditch Co. to the end of the 1870 season, when he left Diamond City and went to Grasshopper Creek, near Montana's earliest mining town of Bannock. There he bought some cows and yearlings brought up from Utah and moved them to the Lemhi Valley, where he went into the cattle business. He developed a ranch on a stream which became known as Peterson Creek, but he later sold that place and moved, first to the Lost River country and then to the vicinity of the present town of Salmon, Idaho. Settling permanently there, William Peterson married Jesse Notewire late in 1888 or early in 1889, and they had two children—a boy, Harold, who lived to the age of 14, and a girl, Jesse, who died in infancy.

Peterson was twice mayor of Salmon and is remembered for bringing electricity to that community by building a powerplant there.

Source: "A Reminiscence of William Peterson," in the manuscript file, Yellowstone Park Reference Library.

JACOB WARD SMITH. Born in New York City, in the year 1830; died in San Francisco, Jan. 23, 1897. A member of the 1870 Washburn party of Yellowstone explorers.

When he was 2 years old, Jacob's father, a New York City baker, died of cholera, and his mother remarried—to Andrew Lang, a butcher. At his stepfather's stall in the Catherine Street Market Jacob learned the butcher's trade, and, whatever his schooling was, is was probably less of an influence than the give-and-take of the market place; anyhow, the man who matured in that environment was very much a hustler, resilient, an inveterate practical joker, and merciless with whatever he came to consider a stupidity.

It was also at the market stall that Jacob met Jeannette, the daughter of Caps. Joel N. Furman, who supplied fish and shellfish from the waters of Long Island Sound. The acquaintance ripened to an engagement upon the young lady's graduation from the Charlottesville Ladies' Seminary in 1858.

The following year, Jacob Smith removed to Virginia City, Nev., where he established the City Market. Jeannette followed him there and they were married in San Francisco on Oct. 26, 1861. During the following years, speculation and politics proved more enticing than the butcher business, and he rapidly accumulated a modest fortune as a stockbroker, speculating in silver. He was also elected an assemblyman for Storey County in Nevada's first legislature, but the decline of the silver mines eventually led to bankruptcy and "Jake," as he was familiarly known, moved to Montana Territory in the summer of 1866.

He immediately went into the tanning business with John Clough—the Montana Hide & Fur Co.—at the corner of Breckenridge and Ewing Streets; but it was a venture that ended in another failure. The Yellowstone adventure took place in the hiatus that followed.

In 1872, Jake returned to San Francisco at the insistence of his wife, and reestablished himself as a broker. Within a decade he was a millionaire, but lost his considerable fortune just as rapidly. His wife returned to the East with their four children in 1885 and divorced him 7 years later. Jake then married Ora C. Caldwell, by whom he had a son before his death by apoplexy in San Francisco.

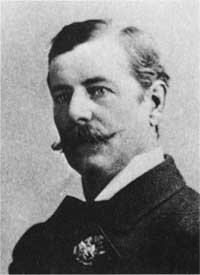

Those are the principal facts in the life of a man who has been presented by Nathaniel P. Langford as "too inconsequent and easy-going to command our confidence or to be of much assistance;" yes, it is quite probable Jake's "good-natured nonsense" and keenly perceptive wit barbed the dignified Langford. Be that as is may be, the likeness we have of Jacob Ward Smith shows a large, good-looking man in a Prince Albert coat, a carnation in the buttonhole, cane and silk top hat in hand; a confident, even imperious man with shrewd eyes well-placed above a Guardsman's mustache. It is not the portrait of a shiftless, ne'er-do-well, but the very image of an American business tycoon of yesterday.

Source: letter from a grandson, Herbert F. Seversmith, on Sept. 13, 1963.

JAMES STEVENSON. Born in Maysville, Ky., Dec. 24, 1840; died in New York City, July 25, 1888. Managing director of the Geological Survey of the Territories (Hayden Survey), and Hayden's assistant during the fieldwork in the Yellowstone region.

"Jim" hailed from the same Kentucky town from whence the legendary John Colter was recruited into the service of the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1803. Like him, this slender, brownhaired 16 year old went forth to a life of adventure in the exploration of the West.

While employed on the surveys of Lt. G. K. Warren and Caps. W. F. Raynolds, he came to know the doctor-turned-geologist Ferdinand V. Hayden, and the old trapper-guide, Jim Bridger. From the one he gained a scientific curiosity, and from the other a taciturn competence. Intervening winters spent with the Sioux and Blackfoot Indians provided him with a knowledge of their language and customs that served him well during later expedisioning and laid the foundation for the ethnological studies of his last years.

The Civil War interrupted this training of a scientific explorer, but it, too, contributed to his development. Enlisting as a private in the 13th New York Regimens, he reached the rank of lieutenant during the war years, and was a seasoned leader of men by the end of that conflict.

In 1866, James Stevenson accompanied Hayden into the badlands of Dakota Territory in a search for fossils, and from that time on he was the assistant of the great geologist in every venture until the Hayden Survey was merged with those of King and Powell to form the U.S. Geological Survey in 1879. His skill in managing the so-often meager finances—supplementing inadequate means by wheedling passes from the railroad and stagecoach companies, borrowing arms, tentage, and wagons from frontier garrisons, and cadging rations from army stores—was genius enough; but he also organized, trained, and often led detachments that moved with dreamlike perfection through a vast expanse of western wilderness, always accomplishing the intended purpose without incident or serious injury.

Quiet and reserved, like the traditional frontiersman he had become, Stevenson spoke no more than he had to, but he meant every word. He might have bragged of his part in the first ascent of the mighty Grand Teton, but he said not a word, nor did he write anything of his strenuous life, for memorabilia were not his forte; yet, when his wild, young scientists hazed the pack mules with stones on the Snake River plain, he was vocal enough—and also gave the culprits extra camp chores as penance.

Upon the formation of the Geological Survey in 1879, James Stevenson became its executive officer, but his interest had turned increasingly to the study of the American Indian, and he was soon detailed to the Bureau of Ethnology to do research in the Southwest for the Smithsonian Institution. He explored cliff and cave dwellings and lived among the Zuni and Hopi Indians, where his rare tact made it possible for him to gather remarkable collections of pottery, costumes, and ceremonial objects. He was stricken with "mountain fever"—probably Rocky Mountain spotted fever—while so employed in 1885, and never really recovered from it.

A relapse in 1887 left Stevenson with a damaged heart, and he was returning to the city of Washington, D.C. with his wife, after an extended convalescence in New England, when he died suddenly at the Gilsey House in New York.

James Stevenson left few records behind, for he was too busy to write much; but he has appropriate memorials in the Indian collections he made for the Smithsonian, and in those place names (an island in Yellowstone Lake and a summit of the Absaroka Range) which Hayden said were given: "In honor of his great services not only during the past season, but for over twelve years of unremitting toil as my assistant, often times without pecuniary reward, and with but little of the scientific recognition that usually comes to the original explorer . . ."

Sources: "James Stevenson," Ninth Annual Report of the United States Geological Survey to the Secretary of the Interior, 1887-88 (Washington, 1889), pp. 42-44; and "James Stevenson," in American Anthropologist, N.S. 18 (1916), 552-59.

BENJAMIN F. STICKNEY. Born in Monroe County, N.Y., Oct. 23, 1838; died in Florida during February 1912. A member of the 1870 Washburn party of Yellowstone explorers, serving as the chief of commissary.

When he was 6 years old, Benjamin's parents moved to Ogle County, Ill., where his education was obtained by desultory attendance at a country school. Much of his time, until he left home as 19, was spent working on the farm, and after that he regularly sent part of his earnings to his parents.

Going to St. Joseph, Mo., Stickney found employment as a bridge carpenter with the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad Co., and, in 1860, he hired out as a teamster for the Lyons & Pullman Co., driving an outfit to Central City, Colo. He then engaged in prospecting and mining, with fair success, until the fall of 1863.

In that year Stickney decided to go to Montana Territory, so he bought a team and wagon and hauled a load of provisions to Virginia City. There he combined freighting with mining for a time. He was eventually able to purchase a claim in Bevin's Gulch, and it yielded him a good return; then he went back to freighting. In that manner he built up a considerable freighting business which he sold to John A. Largens and Joseph Hill in 1872. Thus, he was a freighter at the time of the visit to the Yellowstone region.

Following the sale of his freighting business, Stickney turned to ranching by pre-empting 160 acres of land near the Missouri River just east of Craig, Mont. Grasshoppers ate up his crops for six seasons, but he managed to get by raising cattle. Later he engaged in sheep raising, purchasing 2,498 acres of additional land and leasing some. In 1872, Stickney obtained an interest in the Craig ferry, and after 1875 he operated it alone. He also opened a store in Craig in 1886 and ran it for 10 years.

Stickney married Rachel Wareham on Nov. 3, 1873, and they reared three children.

Sources: A. W. Bowen & Co., Progressive Men of Montana (Chicago, c. 1902), pp. 1823-24; and the obituary file, Montana Historical Society, Helena.

WALTER TRUMBULL. Born in Springfield, Ill., in 1846; died in Springfield, Oct. 25, 1891. A member of the 1870 Washburn party of Yellowstone explorers, writer (contributing to the Helena Rocky Mountain Gazette and The Overland Monthly) and amateur artist.

He was the eldest son of Senator Lyman Trumbull, and, upon completion of his public school education at Springfield, he entered the U.S. Naval Academy. However, he resigned his appointment at the conclusion of the Civil War and embarked on an extended voyage on the Vandalia, under Captain Lee, before taking up journalism as a reporter for the New York Sun.

Prior to his visit to Yellowstone with the Washburn party, Trumbull had been employed under Truman C. Everts as an assistant assessor of internal revenue for Montana Territory. He probably owed the position to the influence of his father, but even that veteran of 16 years in Congress could not protect his son from being displaced in the struggle for patronage that marked President Grant's administration.