|

Yellowstone National Park: Its Exploration and Establishment Introduction |

|

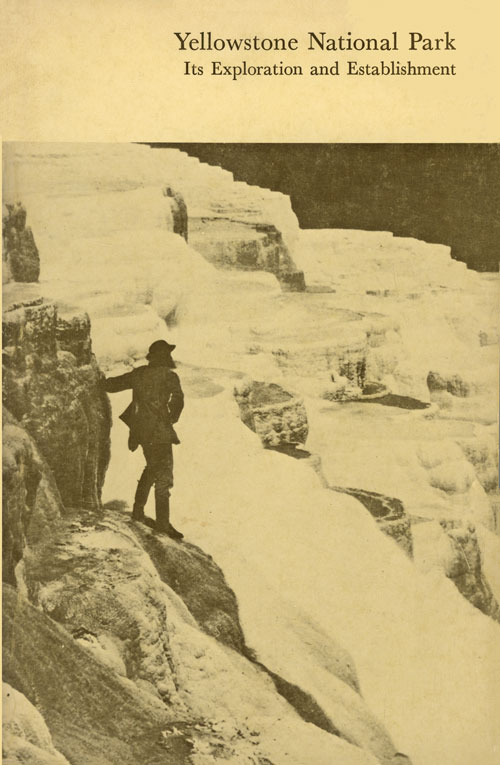

1957 re-enactment of the Washburn, Langford, Doane Party -- Expedition of 1870 -- In Camp at the junction of the Firehole and Gibbon Rivers (Madison Junction) which gave birth to the National Park Idea. Courtesy of National Park Service Historic Photograph Collection. |

The one-hundredth anniversary of the establishment of Yellowstone National Park brought renewed interest in the origin of our first and largest national park. It was an interest which went beyond the primacy and uniqueness of the area, for there the Federal Government entered the business of managing wild lands for recreational use, thus bringing into focus a new concept that had been maturing on the American scene. This "national park idea," as it has come to be known, [1] has burgeoned wonderfully, here and abroad, into park systems that are among the better expressions of man's relationship to his environment.

The particular purpose of this history is to make readily available that body of information which led to establishment of Yellowstone National Park. Since a collection of documentary sources could easily point to false conclusions unless accompanied by some knowledge of the park's place in the development of the whole concept, it should be helpful, before undertaking a presentation of source materials, to trace the growth of Western ideas concerning such nonutilitarian use of land.

Emerson perceived the importance of parks to man when he wrote: "Only as far as the masters of the world have called in nature to their aid, can they reach the height of magnificence. This is the meaning of their hanging-gardens, villas, garden-houses, islands, parks and preserves, to back their faulty personality with these strong accessories." [2] Such artifices are at least as ancient as the hanging gardens built by Nebuchadnezzar at Babylon for the pleasure of his Midian wife. That "chief glory of the great palace" was a tiered structure of brick arches covering 4 acres and rising to the height of 75 feet; an artificial mountain planted with trees, vines, and flowering plants (ingeniously watered from the nearby Euphrates River), and containing cool apartments where the queen could take her ease surrounded by verdure and interesting animals and birds. [3] The hanging gardens were royal and private.

Nor was there any place for common people in the royal gardens of the Persians. Those "vast enclosures that included fruit and ornamental trees, flowers, birds and mammals," were called paradeisos by the Greek soldier-adventurer Xenophon, and knowledge of their magnificence soon passed from the Greek to the Roman world. There, gaudy replicas appeared to grace the estates of the wealthy and the homes of the humble. The poor man's version—generally consisting of little more than courtyard walls painted to resemble the lush gardens of great villas [4] —was pregnant with possibilities. And yet nothing came of it beyond the feeling that has come down to us through the Latin paradisus of the Vulgate Bible to that unsullied English word "paradise." Quite apart from its theological connotation, it evokes visions of a place of ideal beauty and perfect delight. The time was too early for democratization of the park idea.

Instead, the influence of the royal tradition reappeared in the Norman parcs of France—those "unruffled hunting estates" of the feudal nobility. [5] From that source, with its emphasis upon wild property, we have taken our word "park." After the Norman conquest, such hunting parks appeared in England, where the new masters established them in the forests that had belonged to the Saxon kings and, later, upon adjacent common lands.

The way of life that had become established in Saxon England was based upon a village community system where the commonality of lands—group use—had developed under folk-law. With the passage of time, most of the arable lands passed out of the "commons," leaving only the less desirable portions of the townships in that category. But on these remaining lands villagers retained formalized "rights of common," such as pasturage, and access to fuel and building materials.

It would be logical to expect the British to merge their two concepts of game preserves and common holding of land into a form providing the basis for a true park development capable of serving all classes. But they did not. By the Statute of Merton, in 1235 AD., Norman lawyers established the principle that the common was "the Lord's waste," to do with as he pleased, and the Second Statute of Westminster, a half-century later, enabled the lord to enclose common lands. [6] Thus, many commons were converted to deer parks, a trend that established the pattern of park development so firmly that neither romanticism nor industrialism changed it. The English model remained the game preserve nearly to the end of the 19th century—in fact, until the influence of American experience with wilderness parks was felt.

Although the concept of common holding of lands had little influence on park development in Britain, it was very important on these shores. Enough of the commons survived in the mother country that Englishmen were not strangers to the idea of group holding of lands, and the colonists who settled New England also established that form of land holding in their new home. Boston common was established in 1634, and similar tracts were features of most New England towns. But they came to serve a different purpose than in England. Here, they were needed less for grazing and, in a land well endowed with natural resources, not at all for fuel and building materials. Thus the commons became the drill grounds of the militia on training day, and the fair grounds at harvest time. They were also the haunts of itinerants and traveling shows, trysting places, and occasionally even focal points for civil disorders. In brief, they emerged from the colonial period as informal village parks, giving the old English concept of commonality a new direction—toward a public park type of use. The only similar progress elsewhere in the American colonies was in Pennsylvania, where the original plan for Philadelphia allocated a number of squares to public use, with the intention of leaving them as tree-shaded islands within the city. [7]

Game preserves, at least in the European sense, did not appear in colonial America because there was no leisure class to champion such use of the land. Even the Great Ponds Act of 1641, like all colonial conservation, whether concerned with fish, wildlife or timber resources, was defensive. The intention of this measure, by which Massachusetts Bay colony reserved 2,000 bodies of water, with a total area of about 90,000 acres, for "fishing and fowling," was to protect the colony against needs generated by waste and theft. [8]

Further progress of the park idea in colonial New England was impeded by Puritan attitudes toward work, nature, and recreation. Idleness was equated with wickedness, and this work ethic led inexorably to an avoidance of all gay and frivolous things. As for nature, it continued to be viewed very much as William Bradford had written of it in 1620—a "hideous and desolate wilderness, full of wild beasts and wild men," [9] a wilderness to be struggled with and vanquished in accordance with the Biblical injunction to "Be fruitful and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth" (Genesis 1:28). As a consequence, there was no place for recreation, as we know it, in those solemn Puritan communities. Even hunting and fishing were proscribed except as they were a means of procuring food.

The 18th century spawned a philosophy that ultimately changed the New England outlook. From Jean Jacques Rousseau's concept of the "natural man"—that noble savage in his wilderness setting, living a happy and contented life—came a great upsurge of admiration for nature and a sentimental attachment to all things primitive. The basis of this romantic movement was a belief in the "oneness of nature—the great nature, embracing God and man, stars out in space, rocks and crystals here on earth." And so, "nature invaded the consciousness of the world." [10]

What is important here is that romanticism had many voices, crying a love of nature—not alone in the French of Rousseau or the German of Goethe, but also in the English of Wordsworth, Coleridge, Scott, Byron, Shelley, Keats, and Blake. And these voices were heard across the sea, transforming the American view of nature. Hans Huth has traced with meticulous care the development of this appreciative outlook. [11] More, however, was required than a romantic viewpoint to get the stalled park idea moving again.

The missing ingredient was a sense of purpose, and this quality was supplied very early in the 19th century by those men best called the New England philosophers. They were intellectuals whose transcendentalist leanings made them particularly perceptive of their surroundings. [12] What they perceived was the change industrialism was then making in familiar New England localities. The spinning mills and foundries of that "inventive age," seen by the poet Wordsworth developing "to most strange issues," turned pastoral villages into squalid factory towns. Gone was the old, slow moving, and secure rustic life, replaced by urban poverty and its attendant misery and crime. To such thinkers as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Greenleaf Whittier, James Russell Lowell, William Cullen Bryant, Henry David Thoreau, and Ralph Waldo Emerson, the degradation was a concomitant of civilization, and for it they saw but one antidote: a return to nature.

Thoreau eloquently presents the thesis of these New England philosophers in this passage from his essay on "Walking":

I wish to speak a word for Nature, for absolute freedom and wildness, as contrasted with a freedom and culture merely civil, —to regard man as an inhabitant, or a part and parcel of Nature, rather than a member of society. . . . for there are enough champions of civilization: the minister and the school-committee and every one of you will take care of that. [13]

Both Thoreau and Emerson wrote of wondrous nature—this "mother of ours . . . lying all around with such beauty," likened by Emerson to "the music and pictures of the ancient religion." And yet they were realists enough to know there was no returning to the natural state of man. They did not advocate primitivism, but rather a limitation of the unwholesome influences of civilization by keeping closely in touch with nature. Through such a compromise Thoreau could say, "A town is saved, not more by the righteous men in it than by the woods and swamps that surround it," for "in wildness is the preservation of the world." And Emerson thought that "every man is so far a poet as to be susceptible of these enchantments of nature," which are "medicinal, they sober and heal us." [14]

This new conception of nature—as beautiful, kindly, helpful, and restorative, rather than hideous, harsh, obstructive, and degrading—changed the outlook of the American. As one biographer has pointed out, "Imperceptibly Emerson's ideas passed into general currency. Today his influence has spread so wide that, like atmospheric pressure, we are unaware of it. But it has played a vast part in shaping the American way of life." [15] The same may as surely be said of the other New England philosophers. Together they softened the Puritanical outlook of the New England mind, so that it was at last prepared to contribute to the development of the park idea.

The acceptance of this new viewpoint by Americans was manifested in a number of ways, notably in the appearance of a popular literature with outdoor themes, and in the Hudson River school of painting which portrayed landscapes. Such innovations brought nature to the fireside. Equally important, they stimulated a desire to visit scenic places. With improvements in public transportation, first through establishment of comfortable passenger service on river packets and canal boats, and later on the expanding railways, vacation travel to such resorts as Saratoga, White Sulphur Springs, the Adirondacks, Madison-on-Lakes, Appledore, Nahant, Newport, Mount Desert, and Mount Holyoke became feasible. Increasing numbers of the privileged traveled for pleasure.

This acquaintance with the outdoors led naturally to participation in such recreational activities as walking tours, mountain climbing, camping, fishing and hunting, and even to adult games—croquet, in the 1860's, then tennis and golf. [16] Outdoor recreation was not widely indulged in for some time—many people regarded it as a somewhat snobbish activity at first—but at least it soon became respectable.

The park idea flourished in the climate created by that uniquely American type of romanticism generated in New England. The next step beyond the town common (really a town park) was initiated in 1825, when Dr. Jacob Bigelow of Boston called a meeting to consider establishing a town cemetery outside the city. He was convinced of the "impolicy of burials under churches or in church yards approximating closely to the abodes of the living," and was outraged by the "sad, neglected state" of such resting places. His proposal gained the support of influential people, and suitable grounds were found at Mount Auburn, 4 miles from Boston. Here the Nation's first scenic cemetery was dedicated on September 24, 1831. [17]

An area of great beauty, this prototype of the modern cemetery soon drew numerous "parties of pleasure" and couples seeking a trysting place. Such use prompted suggestions that cemeteries ought to be planned "with reference to the living as well as the dead, and therefore should be convenient and pleasant to visitors." In effect, Mount Auburn was serving as a city park, and it was destined to have a far-reaching influence.

Nearly coincident with the establishment of Mount Auburn scenic cemetery came a proposal for another type of park. George Catlin, the artist who ascended the Missouri River in 1832, returned with Indian portraits and a grandiose idea. He would set aside the western high plains from Mexico to Lake Winnepeg as a huge reserve. Here the buffalo and the Indian

might in future be seen, (by some great protecting policy of government) preserved in their pristine beauty and wildness, in a magnificent park, where the world could see for ages to come, the native Indian in his classic attire, galloping his wild horse, with sinewy bow, and shield and lance, amid the fleeting herds of elks and buffaloes. What a beautiful and thrilling specimen for America to preserve and hold up to the view of her refined citizens and the world, in future ages! A nation's park, containing man and beast, in all the wild and freshness of their nature's beauty!

I would ask no other monument to my memory, nor any other enrolment of my name amongst the famous dead, than the reputation of having been the founder of such an institution.

Such scenes might easily have been preserved, and still could be cherished on the great plains of the West, without detriment to the country or its border; for the tracts of country on which the buffaloes have assembled, are uniformly sterile, and of no available use to cultivating man. [18]

Catlin's suggestion was as sterile as it was impractical, and deserves no comment beyond a mention that it probably stimulated Henry Thoreau to pose a surprisingly similar question:

The Kings of England formerly had their forests "to hold the King's game," for sport or food, sometimes destroying villages to create or extend them; and I think that they were impelled by a true instinct. Why should not we, who have renounced the King's authority, have our national preserves, where no villages need be destroyed, in which the bear and panther, and some of the hunter race, may still exist, and not be "civilized off the face of the earth," —our forest, not to hold the King's game merely, but to hold and preserve the King himself also, the lord of creation,—not for idle sport or food, but for inspiration and our own true recreation? [19]

If nothing else, the foregoing quotations are evidence that at least two thinkers had pursued the park idea to its ultimate possibility prior to the middle of the 19th century. Catlin exceeded the practical limits of his outdoor museum by including man among its exhibits, but Thoreau appears to have recognized what a wilderness park could do for man. Together, these suggestions indicate how well the American mind had been prepared for a further progression of the park idea.

A less flamboyant but sounder suggestion came from William Cullen Bryant, who was sufficiently impressed with the burgeoning scenic cemeteries to advocate a city park for New York. It is said that he discussed this idea with friends as early as 1836, but the public proposal was made in the New York Evening Post on July 3, 1844. [20] In 1851 the project for a Central Park got underway with the purchase of necessary lands and the appointment of Frederick Law Olmsted to supervise construction.

Olmsted was a fortunate choice. A student of Andrew Jackson Downing, he benefited from that eminent landscape architect's experience in the development of scenic cemeteries and from his concepts of the Central Park project, which he had ardently promoted. In addition, Olmsted had traveled in Europe and thus was familiar with formal European parks and gardens. From this background he created the prototype of all our great city parks. While not founded on the beauty of wild land, Central Park did simulate it through a judicious blending of formal and informal elements on a large scale. The park idea thereby reached the third stage of its growth on American soil—the city park.

By the same hand the park idea was next elevated to the State level. Olmsted did not always agree with the park commissioners and finally, in May 1863, gave up the superintendency of Central Park, leaving its completion to others. [21] He then undertook the management of the Mariposa estate of Gen. John Charles Frémont in California. Removal to that State brought Olmsted into a fortunate association with the Yosemite Valley and the Big Trees.

These remarkable features of California's central Sierra were well known. A decade earlier an incident involving one of the Calaveras Big Trees—the "Mother of the Forest"—had brought both James Russell Lowell and Oliver Wendell Holmes to condemn commercialization, gaining public support for the conservation of similar wonders. Thus, what was needed in California in the 1860's was a catalytic personality—one capable of directing the existing favorable sentiment toward the protection of the scenic Yosemite Valley as well as the unique Big Trees. Olmsted, fresh from his work on the Nation's first urban park, was just the person to channel the thoughts of influential Californians, and in the year following his arrival, the Congress was persuaded to pass an act whereby the Federal Government made a "grant to the State of California of the 'Yo-Semite Valley,' and of the land embracing the 'Mariposa Big Tree Grove'." As signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on June 30, 1864, this legislation required that the "said State shall accept this grant upon the express conditions that the premises shall be held for public use, resort, and recreation; shall be inalienable for all time." [22]

The significance of the Yosemite grant has been summarized by H. D. Hampton:

The passage of the Act of 1864, granting to California the two tracts of land, did not establish a "national park" nor did it provide for one. No national laws were legislated by which the areas were to be administered and after passage of the act Congress seems to have dismissed the areas from its collective mind. The novelty of the legislation lies in the fact that it provided for land to be reserved for strictly non-utilitarian purposes, thus establishing a precedent or parallel for the later reservation of the Yellowstone region. [23]

The park idea reached its culmination in the establishment of Yellowstone National Park. This was not only the first area of wild land devoted to recreational use under Federal management, but also the pilot model for perfecting that management. It was the Yellowstone experience over nearly two decades which led to establishment of other national parks, and to the growth of a system of national parks dedicated to the protection and wise use of an irreplaceable national heritage.

The great influence of Yellowstone National Park on the park movement generally is not a concern in this history. The following documentation is related only to the historical factors that combined to produce a national park—the first of its kind. Briefly, these were a slow buildup of vague but enticing knowledge, a short period of definitive explorations which established the true nature of wonderland, and the fortunate "park movement" whereby the Federal Government was committed to the management of wild lands for park purposes.

|

|

Last Modified: Tues, Jul 11 2000 07:08:48 am PDT

haines/intro.htm