|

Yellowstone National Park: Its Exploration and Establishment Part III: The Park Movement |

|

|

|

The increased knowledge resulting from definitive exploration of the Yellowstone region spawned a park movement which led directly to establishment of Yellowstone National Park by the Act of Congress signed into law on March 1, 1872. This was the first reservation of wild lands for recreational purposes under the direct management of the Federal government.

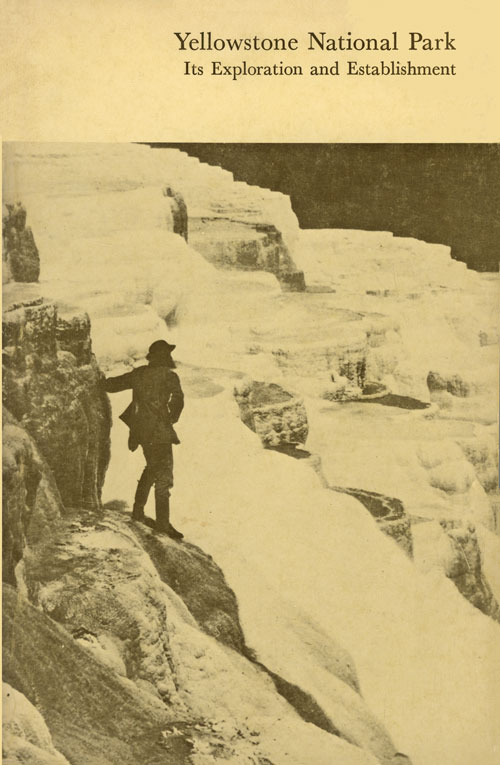

The Great Cañon and Lower Falls of

the Yellowstone,

from Ferdinand Hayden's Geological Surveys of

the Territories (1872)

The field work of the Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories was terminated at Fort Bridger, Wyo., on October 2, 1871, and Ferdinand V. Hayden was back in Washington, D.C., before the end of the month. A letter which reached him there on the 28th probably served to acquaint him with an idea of which he seems not to have been aware—the idea that it was desirable to reserve the Yellowstone region and its wonders for public use, rather than allow its superlatives to pass into private ownership and control. The proposition was essentially the same as those earlier suggestions advanced by Thomas F. Meagher (1865), David E. Folsom (1869), and Cornelius Hedges (1870), but, in this case, it helped to shape a course of action which accomplished the objective.

The letter which came to Hayden's hand was written by A. B. Nettleton on the stationery of "Jay Cooke & Co., Bankers, Financial Agents, Northern Pacific Railroad Company," [1] and it said:

Dear Doctor:

Judge Kelley has made a suggestion which strikes me as being an excellent one, viz.: Let Congress pass a bill reserving the Great Geyser Basin as a public park forever—just as it has reserved that far inferior wonder the Yosemite valley and big trees. If you approve this would such a recommendation be appropriate in your official report? [2]

The Judge Kelley from whom Nettleton received that suggestion was William Darrah Kelley, a Philadelphia jurist who entered Congress on March 4, 1861, as a Republican representative from Pennsylvania, serving in all the Congresses until his death on January 9,1890. Judge Kelley had come under the influence of Asa Whitney in 1845 and, thereafter, was a constant supporter of the idea of spanning the Nation with iron rails. His familiarity with the Yellowstone region was gained from Lieutenant Doane s published report from which he divined the peculiar importance of that area. Being influential in the affairs of Jay Cooke & Co., and familiar with the firm's advertising campaign, he preferred to advance his suggestion through Nettleton rather than directly in Congress.

Judge Kelley's suggestion was forwarded to an influential man. Though Hayden had not previously evidenced any but a scientific interest in the Yellowstone region, he recognized the propriety of reserving its wonders and acted immediately—which is the more surprising considering the pressure he was then under (an official report to be written before the end of the year, a pile of deferred paper work on his desk, and two important magazine articles to write; [3] all that, when his wedding day was only weeks away !).

Hayden's positive response—an assurance that he would present Kelley's suggestion in his official report—led Jay Cooke to write at once to W. Milner Roberts, the Northern Pacific engineer then locating the main line through Montana, as follows:

It is proposed by Mr. Hayden in his report to Congress that the Geyser region around Yellowstone Lake shall be set apart by government as a reservation as park, similar to that of the Great Trees & other reservations in California. Would this conflict with our land grant, or interfere with us in any way? Please give me your views on this subject. It is important to do something speedily, or squatters & claimants will go in there, and we can probably deal much better with the government in any improvements we may desire to make for the benefit of our pleasure travel than with individuals. [4]

The engineer's reply, which was telegraphed from Helena, Mont., on November 21, advised: "Yours October thirtieth & November sixth Reed Geysers outside our grant advise Congressional reservation." [5] Jay Cooke's letter of November 6 has not been located, hence its import is unknown; however, the foregoing exchange is sufficient to reveal important origins of the movement to create a Yellowstone Park.

Evidently, Cooke did not wait to hear from Roberts before actively involving the Northern Pacific in the park movement. On November 9, 1871, the Montana press noted:

Hon. N. P. Langford,—who, by the way, has been back here [Helena] only a few days,—yesterday received a dispatch from Gov. Marshall of Minnesota to return immediately to Minnesota as important business concerning the Northern Pacific Railroad awaited him. Mr. Langford took the Overland coach this evening for Corinne. [6]

Before Langford's arrival in Washington, D.C., about November 14, the Northern Pacific Land Office in New York City received a telegraphic reply from Jno W. Sexton, a member of the directorate of Jay Cooke & Co., informing that Scribner's Magazine had "published nothing of Langford's except article in June Scribner Have no copies here." [7] The inquiry was preparatory—undoubtedly the opening move in that publicity campaign which put the Langford article and selected Jackson photographs in the hands of influential congressmen.

There is a dearth of information regarding the course of events in Washington from the time of Langford's arrival until legislation proposing establishment of a national park in the Yellowstone region was introduced on December 18. However, an item which appeared in a local newspaper on the 7th gives some indication of the thinking prior to that date. According to the editor,

The great falls and wonderful geysers of the Upper Yellowstone, now receiving universal attention, should be forever set apart as a resort for the scientific students and pleasure seekers of the world; and for the convenience of protective local legislation, they should be included within the boundaries of Montana Territory. They are situated beyond our lines and within the jurisdiction of Wyoming; but are practically a barren heritage to our sister Territory, for the reason that rugged, and in winter altogether impassible, mountains separate them from her capital and chief cities. . . . From this side, the Great Falls may be reached and all the surrounding wonders and curiosities explored at any month of the year. . . . As nearly the entire length of the Yellowstone river is in Montana, it is eminently right and proper that its fountains should also be. Congress should donate the extreme Upper Yellowstone, with its mighty cataracts and other marvels to this Territory, to be set apart and protected under appropriate local legislation, as a resort for pleasure and scientific investigation forever. Has not Montana thrown as much gold into the commercial channels of trade and commerce as California had, up to the time that the valley of the Yosemite was thus granted to her by the General Government? And we are satisfied our neighbors of Wyoming would be too reasonable and generous to object to the grant, in the face of the fact that natural circumstances render the prize utterly worthless to them. We understand our wide-awake Delegate will introduce a bill, the present session, asking for appointment of a commission to readjust our boundary, so as to include the Upper Yellowstone, and we suggest to Messrs. Beck and Vivion, our representatives in the Legislature, that a co-operative memorial would be very proper. [8]

It is suggested that the idea presented in the foregoing article—that Montana should be given the Yellowstone region as a grant from the Federal Government, as the State of California had been given the Yosemite Valley—was the original intent of the men who undertook, early in December, the framing of legislation to effect such reservation. However, it was soon evident that the precedent set by the Yosemite grant did not apply because the area Montana wanted lay beyond its boundaries, in Wyoming Territory. It was equally evident that to take from the one for the benefit of the other would not only create trouble between neighbors, but also set a precedent no thinking politician would care to have lurking about lest his own environs somehow fall victim to it. As Hampton has pointed out, "The only way to preserve the area and withhold it from settlement was to place it directly under Federal control." [9]

Regardless of the impropriety of the Yosemite Grant Act as a precedent, its usefulness as a model was not missed. The bill drawn for the consideration of the 42d Congress at its second session has so many points of similarity with the earlier legislation that there can be little doubt from whence it was taken. The parallelism of the two acts is shown in the excerpts arrayed below, which are also in their natural order:

|

YOSEMITE (1864) . . . the said State shall accept this grant upon the express conditions that the premises shall he held for public use, resort, and recreation; shall be inalienable for all time; . . . but leases not exceeding 10 years may be granted for portions of said premises. . . . all incomes derived from leases of privileges to be expended in the preservation and improvement of the property, or the roads leading thereto. . . . |

YELLOWSTONE (1872) . . . is hereby reserved and withdrawn from settlement, occupancy, or sale. . . and dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people. . . . The Secretary may, in his discretion, grant leases for building purposes for terms not exceeding 10 years, of small parcels of ground. . . . . . . all of the proceeds of said leases, and all other revenues that may he derived from any source connected with said park, to be expended under his direction in the management of the same, and the construction of roads and bridle paths therein. |

Both Hampton and Goetzmann have cast Langford and the Montana group as initiators of the park movement. [10] But in truth several interests came together at this time. Hayden, prompted by Nettleton's transmittal of Representative Kelley's suggestion, was thinking in terms of public reservation, and he had important connections with Representative Henry L. Dawes, a powerful figure in the House and one of the guiding hands of the earlier Yosemite legislation. Langford had been summoned to Washington by his brother-in-law in behalf of Jay Cooke and Northern Pacific interests. Delegate Clagett wanted to advance Montana"s interest in the Yellowstone. Cornelius Hedges, although not in Washington at this or any other time in 1871, as his diary reveals, was working in Montana in this cause. All played important roles in forwarding an idea that successive explorations had inspired and popularized and that Jay Cooke and associates had appropriated as useful for their purposes. All these forces united to produce a bill to set aside the Yellowstone country, first on the Yosemite model, and then, as the political perils of that became apparent, as a national park.

Considerable weight has been given to William Horace Clagett's latter-day statement regarding the origin and events of the movement which led to the establishment of Yellowstone National Park. [11] His observations so frequently differ from the facts that they require some mention here as prelude to consideration of the legislative effort on behalf of the Yellowstone region.

Essentially, Clagett exaggerated his own role, picturing himself as the originator of the park idea and the foremost laborer for its attainment. In support of the first, he says:

In the fall of 1870, soon after the return of the Washburn-Langford party, two printers at Deer Lodge City, Mont., went into the Firehole basin and cut a large number of poles, intending to come back the next summer and fence in the tract of land containing the principal geysers, and hold possession for speculative purposes, as the Hutchins family so long held the Yosemite valley. One of these men was named Harry Norton. He subsequently wrote a book on the park. [12] The other one was named Brown. He now lives in Spokane, Wash., and both of them in the summer of 1871 worked in the New Northwest office at Deer Lodge. [13] When I learned from them in the late fall of 1870 or spring of 1871 what they proposed to do, I remonstrated with them and stated that from the description given by them and by members of Mr. Langford's party, the whole region should be made into a National Park and no private proprietorship be allowed.

He goes on to say, on the basis of that remonstrance, that "so far as my personal knowledge goes, the first idea of making it a public park occurred to myself," to which he adds, "but from information received from Langford and others, it has always been my opinion that Hedges, Langford, and myself formed the same idea about the same time."

On the other point, that he took the lead in getting the park established, Clagett says:

I was elected Delegate to Congress from Montana in August, 1871, and after the election, Nathaniel P. Langford, Cornelius Hedges and myself had a consultation in Helena,' [4] and agreed that every effort should be made to establish the Park as soon as possible. . . . In December, 1871, Mr. Langford came to Washington and remained there for some time, and we two counseled together about the Park project. I drew the bill to establish the Park, [15] and never knew Professor Hayden in connection with that bill, except that 1 requested Mr. Langford to get from him a description of the boundaries of the proposed Park. There was some delay in getting the description, and my recollection is that Langford brought me the description after consultation with Professor Hayden. I then filled the blank in the bill with the description, and the bill passed both Houses of Congress just as it was drawn and without any change or amendment whatsoever. [16]

Clagett's account of his connection with the Yellowstone Park legislation ends with the statement, "Langford and I probably did two-thirds, if not three-fourths of all the work connected with its passage." The improbability of that will be evident as the bill is followed through the legislative toils.

Clagett says he "had a clean copy made of the bill and on the first call day in the House, introduced the original there, and then went over to the Senate Chamber and handed the copy to Senator Pomeroy, who immediately introduced it in the Senate.'" Again, Cramton comments:

The proceedings as reported in the Congressional Globe do not seem to me to conform to Mr. Clagett's recollection as to Pomeroy. Senator Pomeroy was the first one to introduce a bill that day in the Senate and the order of introduction of bills came very early in the day's proceedings. While that order of business likewise came early in the House, Mr. Clagett was not the first one to introduce a bill in the House, but followed quite a number of others. It is evident he could not have introduced the bill first and then gone over to the Senate to give a copy to Senator Pomeroy in time for Senator Pomeroy to take the action he did. [17]

A search was made for the original Senate bill in the hope that it might throw some light upon the question of authorship, but the document appears not to have been saved. Likewise, the file of Senator Pomeroy's Committee on the Public Lands is barren of even a mention of the Yellowstone bill. [18]

Clagett's attempt to have his bill referred to the Committee on Territories (it was sent to the Committee on the Public Lands on the motion of Representative Stevenson) ended his efforts on behalf of the legislation—insofar as the public record is concerned. However, there is no reason for doubting a later statement that, between Hayden, Langford, and Clagett, "there was not a single member of Congress in either House who was not fully posted by one or the other of us in personal interviews." [19]

Another part of the campaign to influence the legislators was carried on by Hayden, who "brought with him a large number of specimens from different parts of the Park, which were on exhibition in one of the rooms of the Capitol or in the Smithsonian Institution (one or the other), while Congress was in session," [20] and he is also credited with exhibiting the specimens and explaining the geological and other features of the proposed park. Unfortunately, neither Hayden nor Langford left an adequate record of his activities during this period, and, except for the brief statement just quoted, an assessment will have to rest on the statement of historian Chittenden, who says of their work: [21]

Dr. Hayden occupied a commanding position in this work, as representative of the government in the explorations of 1871. He was thoroughly familiar with the subject, and was equipped with an exhaustive collection of photographs and specimens gathered the previous summer. These were placed on exhibition and were probably seen by all members of Congress. They did a work which no other agency could do, and doubtless convinced every one who saw them that the region where such wonders existed should be carefully preserved to the people forever. Dr. Hayden gave to the cause the energy of a genuine enthusiasm, and his work that winter will always hold a prominent place in the history of the Park. [22]

Mr. Langford, as already stated, had publicly advocated the measure in the previous winter. He had rendered service of the utmost importance, through his publications in Scribner's Magazine in the preceding May and June. Four hundred copies of these magazines were brought and placed upon the desks of members of Congress on the days when the the measure was to be brought to vote. During the entire winter, Mr. Langford devoted much of his time to the promotion of this work. [23]

Truman C. Everts, who had just come into prominence through the appearance of his article, "Thirty-seven Days of Peril," in Scribner's Monthly (November, 1871), entered the Washington scene early in January, but the only evidence yet found to indicate a connection with the park movement is his letter transmitting a set of Jackson's photographs to J. Gregory Smith, president of the Northern Pacific Railroad. [24]

A latter-day effort to turn Thomas Moran into "The Father of National Parks'" hints that he, also, was involved in promoting the park movement; [25] however, there is no factual basis for such an interpretation. His great painting, an 8- by 15-foot oil developed from a sketch of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone as he saw it from Grand View in 1871, was yet incomplete at the time the Yellowstone Act was signed into law. In a letter to Hayden shortly thereafter he wrote:

I have been intending to write to you for some month's past but have been so very busy with Yellowstone drawings, & so absorbed in designing & painting my picture of the Great Cañon that I could not find the time to write to anybody. The picture is now more than half finished & I feel confident that it will produce a most decided sensation in Art Circles. . . . I east all my claims to being an Artist, into this one picture of the Great Cañon & am willing to abide by the judgement upon it. [26]

Whether or not the public came to look fondly upon Hayden's guest as Thomas "Yellowstone" Moran, the fact remains that he was not among those who labored significantly to establish our first national park.

Before considering the progress of the Yellowstone legislation, it is appropriate to note the paucity of editorial comment upon such a novel proposal. Only two Western newspapers appear to have grasped the significance of it—the Deer Lodge New North-West (Montana) and the Virginia City Daily Territorial Enterprise (Nevada). The former, after calling the Yellowstone region "a very Arcana Inferne," suggested that

. . . to it will come in the coming years thousands from every quarter of the globe, to look with awe upon its amazing phenomena, and with pen, pencil, tongue and camera publish its marvels to the enlightened realms. Let this, too, be set apart by Congress as a domain retained unto all mankind, (Indians not taxed, excepted), and let it be esto perpetua. [27]

The Territorial Enterprise, with less flamboyance noted:

The Hon. N. P. Langford of Montana, the leader [sic] of the famous Yellowstone Expedition of 1870, and several scientific and literary gentlemen, is engaged in an effort to have the Yellowstone region declared a National Park. The district, of which some features have been described in Scribner's Monthly, is said to be unadapted to agriculture, mining or manufacturing purposes, and it is proposed to have its magnificent scenery, hot springs, geysers and cataracts forever dedicated to public uses as a grand national reservation. Congress is to be petitioned to this effect. [28]

Yellowstone Lake by Thomas Moran,

from Ferdinand Hayden's Geological Surveys of the Territories

(1872)

Returning to the Yellowstone legislation, it was the Senate version of the bill—Pomeroy's S. 392—which prospered. On January 22, the Senator from Kansas attempted to report his bill from the Committee on Public Lands in a proceeding which is reported thus:

Mr. POMEROY. I am instructed by the Committee on Public Lands to report back and recommend the passage of the bill (S. No. 392) to set apart a certain tract of land lying near the headwaters of the Yellowstone river as a public park. It will be remembered that an appropriation was made last year of about ten thousand dollars to explore that country. Professor Hayden and party have been there, and this bill is drawn on the recommendation of that gentleman to consecrate for public uses this country as a public park. It contains about forty miles square. It embraces those geysers, those great natural curiosities which have attracted so much attention. It is thought that it ought to be set apart for public uses. I would like to have the bill acted on now. The committee felt that if we were going to set it apart at all, it ought to be done before individual preemptions or homestead claims attach.

The VICE PRESIDENT. The Senator from Massachusetts and the Senator from Kentucky both gave way only for current morning business, but the Senator from Kansas now asks unanimous consent for the consideration of the bill which he has just reported.

Several Senators objected.

Mr. POMEROY. Then I withdraw the report for the present. [29]

The following day Senator Pomeroy presented his bill again:

Mr. POMEROY. The Committee on Public Lands, to whom was referred the bill (S. No. 392) to set apart a tract of land lying near the headwaters of the Yellowstone as a public park, have directed me to report it back without amendment, to recommend its passage, and to ask that it have the present consideration of the Senate.

The VICE PRESIDENT. The Senator from Kansas asks unanimous consent of the Senate for the present consideration of the bill reported by him. It will be reported in full, subject to objection.

The Chief Clerk read the bill.

The Committee on Public Lands reported the bill with an amendment in line nineteen to strike out the words "after the passage of this act," and in line twenty, after the word "upon", to insert the words "or occupying a part of;" so as to make the clause read, "and all persons who shall locate or settle upon or occupy any part of the same, or any part thereof, except as hereinafter provided, shall be considered as trespassers and removed therefrom."

The VICE PRESIDENT. Is there objection to the present consideration of this bill?

Mr. CAMERON. I should like to know from somebody having charge of the bill, in the first place, how many miles square are to be set apart, or how many acres, for this purpose, and what is the necessity for the park belonging to the United States.

Mr. POMEROY. This bill originated as the result of the exploration, made by Professor Hayden, under an appropriation of Congress last year. With a party he explored the headwaters of the Yellowstone and found it to be a great natural curiosity, great geysers, as they are termed, water-spouts, and hot springs, and having platted the ground himself, and having given me the dimensions of it, the bill was drawn up, as it was thought best to consecrate and set apart this great place of national resort, as it may be in the future, for the purposes of public enjoyment.

Mr. MORTON. How many square miles are there in it?

Mr. POMEROY. It is substantially forty miles square. It is north and south forty-four miles, and east and west forty miles. He was careful to make a survey so as to include all the basin where the Yellowstone has its source.

Mr. CAMERON. That is several times larger than the District of Columbia.

Mr. POMEROY. Yes, Sir. There are no arable lands ; no agricultural lands there. It is the highest elevation from which our springs descend, and as it cannot interfere with any settlement for legitimate agricultural purposes, it was thought that it ought to be set apart early for this purpose. We found when we set apart the Yosemite valley that there were one or two persons who had made claims there, and there has been a contest, and it has finally gone to the Supreme Court to decide whether persons who settle on unsurveyed lands before the Government takes possession of them by any special act of Congress have rights as against the Government. The court has held that settlers on unsurveyed lands have no rights as against the Government. The Government can make an appropriation of any unsurveyed lands, notwithstanding settlers may be upon them. As this region would be attractive only on account of preempting a hot spring or some valuable mineral it was thought such claims had better be excluded from the bill.

There are several Senators whose attention has been called to this matter, and there are photographs of the valley and the curiosities which Senators can see. The only object of the bill is to take early possession of it by the United States and set it apart, so that it cannot be included in any claim or occupied by any settlers.

Mr. TRUMBULL. Mr. President—

The VICE PRESIDENT. The Chair must state that the Senate have not yet given their consent to the present consideration of the bill. The Senator from Pennsylvania desired some explanation in regard to it. Does he reserve the right to object?

Mr. CAMERON. I make no objection.

Mr. THURMAN. I object.

Mr. SHERMAN. I will not object if it is not going to lead to debate.

Mr. TRUMBULL. It can be disposed of in a minute.

Mr. THURMAN. I object to the consideration of this bill in the morning hour. I am willing to take it up when we can attend to it, but not now. [30]

The Yellowstone bill was again brought up for consideration by the Senate on January 30—in its regular order. This crucial session is recorded in The Congressional Globe (p. 697) under the heading "Yellowstone Park" a term not used previously in debate. Continuing from the record:

The VICE PRESIDENT. The bill (S. No. 392) to set apart a certain tract of land lying near the headwaters of the Yellowstone river as a public park, taken up on the motion of the Senator from Kansas, which was reported by the Committee on Public Lands, is now before the Senate as in Committee of the Whole.

The bill was read— [followed by a restatement of the amendments previously reported by the Committee on Public Lands].

The VICE PRESIDENT. These amendments will be regarded as agreed to unless objected to. They are agreed to.

Mr. ANTHONY. I observe that the destruction of game and fish for gain or profit is forbidden. I move to strike out the words "for gain or profit,"" so that there shall be no destruction of game there for any purpose. We do not want sportsmen going over there with their guns.

Mr. POMEROY. The only object was to prevent the wanton destruction of the fish and game; but we thought parties who encamped there and caught fish for their own use ought not to be restrained from doing so. The bill will allow parties there to shoot game or catch fish for their own subsistence. The provision of the bill is de signed to stop the wanton destruction of game or fish for merchandise.

Mr. ANTHONY. I do not know but that that covers it. What I mean is that this park should not be used for sporting. If people are encamped there, and desire to catch fish and kill game for their own sustenance while they remain there, there can be no objection to that; but I do not think it ought to be used as a preserve for sporting.

Mr. POMEROY. I agree with the Senator, but I think the bill as drawn protects the game and fish as well as can be done.

Mr. ANTHONY. Very well; I am satisfied.

The VICE PRESIDENT. The Senator does not insist on his amendment?

Mr. ANTHONY. No, sir.

Mr. TIPTON. I think if this is to become a public park, a place of great national resort, and we allow the shooting of game or the taking of fish without any restriction at all, the game will soon be utterly destroyed. I think, therefore, there should be a prohibition against their destruction for any purpose, for if the door is once opened I fear there will ultimately be an entire destruction of all the game in that park. [31]

Mr. POMEROY. It will be entirely under the control of the Secretary of the Interior. He is to make the rules that shall govern the destruction and capture of game. I think in that respect the Secretary of the Interior, whoever he may be, will be as vigilant as we would be.

The VICE PRESIDENT. Perhaps the Secretary had better report the sentence referred to by Senators as bearing on this question, and then any Senator who desires to amend can move to do so.

The Chief Clerk read as follows:

"He shall provide against the wanton destruction of the fish and game found within said park, and against their capture or destruction for the purposes of merchandise or profit."

Mr. EDMUNDS. I hope this bill will pass. I have taken some pains to make myself acquainted with the history of this most interesting region. It is so far elevated above the sea that it cannot be used for private occupation at all, but it is probably one of the most wonderful regions in that space of territory which the globe exhibits anywhere, and therefore we are doing no harm to the material interests of the people in endeavoring to preserve it. I hope the bill will pass unanimously.

Mr. COLE. I have grave doubts about the propriety of passing this bill. The natural curiosities there cannot be interfered with by anything that man can do. The geysers will remain, no matter where the ownership of the land may be, and I do not know why settlers should be excluded from a tract of land forty miles square, as I understand this to be, in the Rocky mountains or any other place. I cannot see how the natural curiosities can be interfered with if settlers are allowed to approach them. I suppose there is very little timber on this tract of land, certainly no more than is necessary for the use and convenience of persons going upon it. I do not see the reason or propriety of setting apart a large tract of land of that kind in the Territories of the United States for a public park. There is abundance of public park ground in the Rocky mountains that will never be occupied. It is all one great park, and never can be anything else; large portions of it at all events. There are some places, perhaps this is one, where persons can and would go and settle and improve and cultivate the grounds, if there be ground fit for cultivation.

Mr. EDMUNDS. Has my friend forgotten that this ground is north of latitude forty, and is over seven thousand feet above the level of the sea? You cannot cultivate that kind of ground.

Mr. COLE. The Senator is probably mistaken in that. Ground of a greater height than that has been cultivated and occupied.

Mr. EDMUNDS. In that latitude?

Mr. COLE: Yes, sir. But if it cannot be occupied and cultivated why should we make a public park of it? If it cannot be occupied by man, why protect it from occupation? I see no reason in that. If nature has excluded men from its occupation, why set it apart and exclude persons from it? If there is any sound reason for the passage of the bill, of course I would not oppose it; but really I do not see any myself. [32]

Mr. TRUMBULL. I think our experience with the wonderful natural curiosity, if I may so call it, in the Senator"s own State, should admonish us of the propriety of passing such a bill as this. There is the wonderful Yosemite valley, which one or two persons are now claiming by virtue of preemption. Here is a region of country away up in the Rocky mountains, where there are the most wonderful geysers on the face of the earth; a country that is not likely ever to be inhabited for the purposes of agriculture; but it is possible that some person may go there and plant himself right across the only path that leads to these wonders, and charge every man that passes along between the gorges of these mountains a fee of a dollar or five dollars. He may place an obstruction there, and toll may be gathered from every person who goes to see these wonders of creation.

Now this tract of land is uninhabited; nobody lives there; it was never trod by civilized man until within a short period. Perhaps a year or two ago was the first time that this country was ever explored by anybody. It is now proposed, while it is in this condition, to reserve it from sale and occupation in this way. I think it is a very proper bill to pass, and now is the time to enact it. We did set apart the region of country on which the mammoth trees grow in California, and the Yosemite valley also we have undertaken to reserve, but there is a dispute about it. Now, before there is any dispute as to this wonderful country, I hope we shall except it from the general disposition of the public lands, and reserve it to the Government. At some future time, if we desire to do so, we can repeal this law if it is in anybody's way; but now I think it a very appropriate bill to pass. [33]

The bill was reported to the Senate as amended; and the amendments were concurred in. The bill was ordered to be engrossed for a third reading, read a third time, and passed.

The passage of the Senate version of the Yellowstone bill was noted briefly in the Washington Evening Star: "Mr. Pomeroy called up the bill setting apart the Yellowstone Valley as a public park forever, which was passed,"" [34] but the more discerning coverage appeared in Montana. On receipt of word of the Senate's action, a Helena newspaper remarked:

We have not seen the text of this particular bill, and cannot say if it is identical with that introduced in the House by our Delegate, but presume it to be essentially the same; and judging from the readiness with which the idea has been taken up, put into shape, and passed the Senate, there can be little doubt that very soon it will receive the sanction of the necessary parties and become a law. In fact, since the idea was first conceived by the party of gentlemen from this city, who visited this region of wonders in the summer of 1869 [sic], and gave to the world the first reliable reports concerning its marvelous wealth of natural curiosities, the project has gained ground with surprizing rapidity. The letters of Mr. Hedges, first published in the HERALD, the lectures of Mr. Langford, the articles of Mr. Trumbull, and later still, the story of [the] peril and adventure of Mr. Everts, all of the same party, were widely circulated by the press of the country, and not merely excited a passing curiosity, but created a living, general interest that has since received strength and larger proportions by the publication of Lieutenant Doane's official report to the War Department of the same expedition; followed, as it was, by the expedition of Professor Hayden, during the last summer, under the patronage of the Smithsonian Institution, with its fully appointed corps of scientific gentlemen and distinguished artists, whose reports have more than confirmed all descriptions of the Washburn party. Such, in brief, has been the origin and progress of this project now about to receive a definite and permanent shape in the establishment of a National Park. It will be a park worthy of the Great Republic. If it contains the proportions set forth in Clagett's bill, it will embrace about 2,500 square miles, and include the great canyon, the Falls and Lake of the Yellowstone, with a score of other magnificent lakes, the great geyser basin of the Madison, and thousands of mineral and boiling springs. Should the whole surface of the earth be gleaned, another spot of equal dimensions could not be found that contains on such a magnificent scale one-half the attractions here grouped together. [35]

The editor also noted that "Without a doubt the Northern Pacific Railroad will have a branch track penetrating this Plutonian region, and few seasons will pass before excursion trains will daily be sweeping into this great park thousands of the curious from all parts of the world." Thus, citizens of Montana Territory "who would look upon this scene in its wild, primitive beauty, before art has practised any of its tricks upon nature," were advised to visit the area at once.

That there was a strong sentiment, locally, favoring such a park movement is evidenced by the appearance at just this time of the memorial to Congress which had originated in the Montana Legislature as Council Joint Memorial No. 5. This interesting document, authored by Cornelius Hedges and introduced by Councilman Seth Bullock, was addressed "To the Honorable Senate and House of Representatives of the United States in Congress assembled," which were reminded that

. . . a small portion of the Territory of Wyoming, as now constituted in its extreme northwest corner, is separated from the main portion of that Territory by the almost impassable ranges of mountains that divide the headwaters of the Madison from those of the Snake river on the south, connecting with those dividing the waters of the Yellowstone from those of Big Horn and Wind Rivers on the east; that this portion of Wyoming is only accessible from the side of Montana; contains the heads of streams whose course is wholly through Montana; while through the enterprise of citizens of Montana it has been thoroughly explored, and its innumerable and magnificent array of wonders in geysers, boiling springs, mud volcanoes, burning mountains, lakes, and waterfalls brought to the attention of the world. Your memorialists would, therefore, urge upon your Honorable bodies that the said portion of Wyoming be ceded to Montana by an extension of its southern line from 111 degrees of longitude east and north along the crest of said mountain ranges dividing the headwaters of the Madison and Yellowstone rivers from those of the Snake, Bighorn and Wind Rivers, till it intersects with the present southern line of Montana, on the 45th degree of latitude. Your memorialists would further urge that the above described district of country, with so much more of the present Territory of Montana as may be necessary to include the Lake, Great Falls, and Canyon of the Yellowstone, the great geyser basin of the Madison, with its associate [sic] boiling, mineral and mud springs, as may be determined from the surveys made by Prof. Hayden and party past season, or to be determined by surveys hereafter to be made, be dedicated and devoted to public use, resort and recreation, for all time to come as a great National Park, under such care and restrictions as to your Honorable bodies may seem best calculated to secure the ends proposed. [36]

But, if there was evident support for the park legislation, its success in the Senate also raised misgivings which eventually hardened into a very determined opposition. This antipathy arose out of the effort of Harry R. Horr and James C. McCartney to get their tract of land at Mammoth Hot Springs (where they had located as squatters during the summer of 1871) excepted from the provisions of the bill. As soon as the text of the bill was made available, these settlers began circulating a petition by means of which they hoped to influence Congress in their favor, [37] but in that they were disappointed.

A little more than 2 weeks later the Helena Rocky Mountain Weekly Gazette took its stand with the settlers, commenting on the park proposal in these words:

As for ourselves we regard the project with little favor, unless Congress will go still further and make appropriations to open carriage roads through, and hostels in, the reserved district, so that ordinary humanity can get into it without having to ride on the "Hurricane deck" of a mule. . . . Already private enterprise was taking measures to render the country accessible to such tourists as are not strong enough to endure the fatigues of a regular exploring expedition. . . .

If Congress sets off that scope of country as proposed, all these private enterprises will immediately cease, and as it is not at all likely that the Government will make any appropriations to open roads or hostelries, the country will be remanded into a wilderness and rendered inaccessible to the great mass of travelers and tourists for many years to come. . . .

We are opposed to any scheme which will have a tendency to remand it into perpetual solitude, by shutting out private enterprise and by preventing individual energy from opening the country to the general traveling public. . . . [38]

The Gazette continued to champion the Yellowstone settlers and the issue they had raised, and will be heard from again.

Yellowstone Geyers,

from Ferdinand Hayden's Geological Surveys of the Territories

(1872)

Of greater importance, while the Yellowstone legislation was yet under consideration in Congress, was the effect of a number of popular and scientific articles which appeared in various publications. The artist with the Hayden Survey party in 1871, Henry W. Elliott, was also a field correspondent for Leslie's Illustrated, and he provided that magazine with a brief description of the Yellowstone region as he had seen it. [39] Captain Barlow, whose small party had accompanied Hayden's through the Yellowstone region in 1871, provided the Chicago Evening Journal with a detailed account, and later prepared an official report. [40] But it was geologist Ferdinand V. Hayden who was most influential in both the popular and scientific medium.

Hayden's article in Scribner's Monthly (written to accompany Thomas Moran"s sketches) reached a large and influential body of readers, to whom he brought this message: "Why will not Congress at once pass a law setting it [the Yellowstone region] apart as a great public park for all time to come, as has been done with that far inferior wonder, the Yosemite Valley?" [41] His scientific article, though written prior to the passage of the Yellowstone legislation, did not appear until later; [42] thus, the closing statement, another powerful call for reservation of the Yellowstone region as a national park, could have influenced only those who had seen Hayden's draft. Regardless, the title, "On the Yellowstone Park," is a measure of his considerable faith in the legislation then awaiting the action of the House of Representatives.

Before following the Yellowstone legislation to its conclusion, it is necessary to note a letter written to F. V. Hayden on February 19. In it, George A. Crofutt, author of a prominent tourist guidebook, expressed his indignation at the failure of a news item in the New York World of the previous day to give the geologist proper credit for the maturing park scheme. [43] Evidently, N. P. Langford had been identified as the king-pin of the movement, and not just by the World; similar releases have been found in the St. Joseph Herald (Missouri), and the Virginia Daily Territorial Enterprise (Nevada). [44]

While the Senate bill, S. 392, was making such splendid progress, its counterpart in the House, Delegate Clagett's H.R. 764, remained with the Committee on Public Lands, unreported for more than 2 months. During this time, the only action taken on the measure was a request from the chairman of the subcommittee to the Secretary of the Interior for a copy of Hayden's report. In his letter to Secretary Delano, January 27, 1872, Representative Mark H. Dunnell stated:

The Committee on Public Lands has under consideration the Bill to set apart some land for a Park in Wyoming T. As Ch. of a subcommittee on the bill, I will be pleased to receive the report made by Prof. Hayden or such report as he may be able to give us on the subject. [45]

Dunnell"s request reached the Secretary on the 29th and was answered by him the same day. [46] His reply not only provided the desired information in the form of a brief special report prepared by Hayden, but also included this comment: "I fully concur in his recommendations, and trust that the bill referred to may speedily become a law."

Hayden's full report was in draft at that time, for Capt. John Barlow had mentioned seeing and approving it earlier; [47] however, it was not suited to the purpose at hand and a synopsis was substituted. This document was held by the House Committee on Public Lands for nearly a month without further action; in the vernacular, they "sat upon it."

Meanwhile, the bill which had passed the Senate—Pomeroy's S. 392— went over to the House and was brought up on February 27 in the regular order of business. Immediately upon its introduction, the following exchange took place: [48]

Mr. SCOFIELD. I move that the bill be referred to the Committee on the Public Lands.

Mr. DAWES. I hope that bill will be put upon its passage at once. It seems to be a meritorious measure.

Mr. TAFFE. I move that it be referred to the Committee on the Territories.

Mr. SCOFIELD. At the request of the gentleman from Massachusetts [Rep. Dawes], I withdraw my motion.

Mr. HAWLEY. This question was referred to the Committee on the Public Lands in a House bill exactly similar in all its respects to this bill; it was considered by that committee, and the gentleman having it in charge was instructed to report it favorably to the House, [49] and if the committee were on call it would be reported.

Mr. DUNNELL. I was instructed by the committee to ask the House to pass a bill precisely like the bill passed by the Senate. I have examined the question thoroughly and with a great deal of care, and I am satisfied that the bill ought to pass. [50]

Mr. DAWES. It seems very desirable that the bill should pass as early as possible, in order that the depredations in that country shall be stopped.

Mr. FINKELNBURG. I would like to have the bill read.

The bill was read. [The text of the bill, as amended by the Senate, was given in full.]

Mr. DAWES. This bill follows the analogy of the bill passed by Congress six or eight years ago, setting apart the Yosemite valley and the "big tree country" for the public park, with this difference: that that bill granted to the State of California the jurisdiction over that land beyond the control of the United States. This bill reserves the control over the land, and preserves the control over it to the United States, [51] so that at any time when it shall appear that it will be better to devote it to any other purpose it will be perfectly within the control of the United States to do it.

It is a region of country seven thousand feet above the level of the sea, where there is frost every month of the year, and where nobody can dwell upon it for the purpose of agriculture, containing the most sublime scenery in the United States excepting the Yosemite valley, and the most wonderful geysers ever found in the country. [52]

The purpose of this bill is to preserve that country from depredations, but to put it where if the United States deems it best to appropriate it to some other use it can be used for that purpose. It is rocky, mountainous, full of gorges, and, from the descriptions given by those who visited it during the last summer, is unfit for agricultural purposes; but if upon a more minute survey it shall be found that it can be made useful for settlers, and not depredators, it will be perfectly proper this bill should pass; it will infringe upon no vested rights, the title to it will still remain in the United States, different from the ease of the Yosemite valley, where it now requires the coordinate legislative action of Congress and the State of California to interfere with the title. [53] This bill treads upon no rights of the settler, infringes upon no permanent prospect of settlement of that Territory, and it receives the urgent and ardent support of the Legislature of the Territory, and of the Delegate himself, who is unfortunately now absent, and of those who surveyed it and brought the attention of the country to its remarkable and wonderful features. We part with no control ; we put no obstacle in the way of any other disposition of it; we but interfere with what is represented as the exposure of that country to those who are attracted by the wonderful descriptions of it by the reports of the geologists, and who are going there to plunder this wonderful manifestation of nature.

Mr. TAFFE. I desire to ask the gentleman a question, and it is whether this measures does not interfere with the Sioux reservation and in the next place I know that that treaty, if you call it a treaty, which I never thought it was, because the law raising the commission said the treaty should be ratified by Congress and not by the Senate, and under that you abandoned the right to go into the country between the Missouri river and the Big Horn mountain. Now, I ask the gentleman if this bill does not infringe upon the territory set apart for these Indian tribes?

Mr. DAWES. The gentleman has my answer, because he has heard it a great many times here. Both Houses have acted upon the theory that all of the treaties made by this commission are simple matters of legislation.

Mr. TAFFE. That does not answer my question as to the right of settlers to go upon this land. If that is not included in the treaty, then settlers have a right to go upon that land to-day; if that is the treaty, then nobody has a right to go into the country between the Big Horn mountain and the Missouri river except with the consent of these Indian tribes. [54]

Mr. DAWES. That may be; but the Indians can no more live there than they can upon the precipitous sides of the Yosemite valley.

Mr. SCOFIELD. I call the previous question.

The previous question was seconded and the main question ordered, which was upon the third reading of the bill.

Mr. STEVENSON. I ask leave to have printed in the Globe some remarks upon this bill.

No objection was made; and leave was accordingly granted. [See Appendix] [55]

The question was upon ordering the bill to be read a third time; and upon a division there were—ayes 81, noes 41.

So the bill was ordered to be read a third time; and it was accordingly read the third time.

The question was upon the passage of the bill.

Mr. MORGAN. Upon that question I call for the yeas and nays.

The question was taken upon ordering the yeas and nays; and there were twenty-seven in the affirmative.

So (the affirmative being one fifth of the last vote) the yeas and nays were ordered.

The question was then taken; and it was decided in the affirmative— yeas 115, nays 65, not voting 60; as follows:

YEAS—Messrs. Ames, Archer, Averill, Banks, Barber, Barry, Beatty, Beveridge, Bigby, Biggs, Bingham, Austin Blair, Boles, George M. Brooks, Buckley, Buffiington, Burchard, Burdett, Roderick R. Butler, William T. Clarke, Cobb, Coburn, Conger, Cotton, Cox, Crebs, Crocker, Darrall, Dawes, Dickey, Donnan, Duell, Dunnell, Eames, Farnsworth, Farwell, Wilder D. Foster, Frye, Garfield, Hale, Hambleton, Harmer, George E. Harris, Havens, Hawley, Hays, Gerry W. Hazelton, John W. Hazelton, Hereford, Hill, Hoar, Hooper, Houghton, Kelley, Kellogg, Kendall, Ketcham, Lamport, Leach, Maynard, McCrary, McGrew, McHenry, McJunkin, McNeely, Mercur, Merriam, Mitchell, Monroe, Leonard Myers, Negley, Orr, Packard, Packer, Palmer, Peck, Pendleton, Aaron F. Perry, Peters, Potter, Ellis H. Roberts, Rusk, Sargent, Sawyer, Scofield, Seeley, Sessions, Sheldon, Shellabarger, Sherwood, Shoemaker, Sloss, H. Boardman Smith, John A. Smith, Snapp, Snyder, Sprague, Stevens, Stevenson, Stoughton, Swann, Washington Townsend, Turner, Tuthill, Twichell, Upson, Wakeman, Waldron, Wallace, Wheeler, Willard, Williams of New York, Jeremiah M. Wilson, John T. Wilson, and Wood— 115.

NAYS—Messrs. Acker, Arthur, Barnum, Beck, Bird, Braxton, Caldwell, Coghlan, Comingo, Conner, Critcher, Crossland, DuBose, Duke, Eldredge, Finkelnburg, Forker, Henry D. Foster, Garrett, Getz, Golladay, Griffith, Haldeman, Handley, Hanks, John T. Harris, Hay, Herndon, Hibbard, Holman, Kerr, Killinger, Lewis, Lowe, Manson, McClelland, McCormick, McIntyre, Benjamin F. Meyers, Morgan, Niblack, Eli Perry, Price, Prindle, Rainey, Read, Edward Y. Rice, John M. Rice, William R. Roberts, Shanks, Slater, Slocum, R. Milton Speer, Thomas J. Speer, Starkweather, Strong, Taffe, Terry, Tyner, Van Trump, Voorhees, Waddell, Whitthorne, Winchester, and Young—65.

NOT VOTING—Messrs. Adams, Ambler, Bell, James G. Blair, Bright, James Brooks, Benjamin F. Butler, Campbell, Carroll, Freeman Clarke, Creely, Davis, De Large, Dox, Elliott, Ely, Charles Foster, Goodrich, Halsey, Hancock, Harper, King, Kinsetta, Lamison, Lansing, Lynch, Marshall, McKee, McKinney, Merrick, Moore Morey, Morphis, Hosea W. Parker, Isaac C. Parker, Peree, Platt, Poland, Porter, Randall, Ritchie, Robinson, Rogers, Roosevelt, Shober, Worthington C. Smith, Storm, Stowell, St. John, Sutherland, Sypher, Thomas, Dwight Townsend, Vaughan, Walden, Walls, Warren, Wells, Whiteley, and Williams of Indiana—60.

So the bill was passed. [56]

Mr DAWES moved to reconsider the vote by which the bill was passed; and also moved that the motion to reconsider be laid on the table.

The latter motion was agreed to.

The enrolled bill was signed by the Speaker of the House on the following day, and, though it had yet to be approved by the President,the success of the measure was widely noted. The St. Louis Times (Missouri), and the Denver Daily Rocky Mountain News (Colorado), provided telegraphic notices that the "Yellowstone Valley" in Wyoming and Montana had been set apart, as a "national park" or a "public park," but only Montana s Helena Daily Herald had any serious comment to offer so soon. In its front-page article, this proponent of the park movement stated: [57]

Our dispatches announce the passage in the House of the Senate bill setting apart the Upper Yellowstone Valley for the purposes of a National Park. The importance to Montana of this Congressional enactment cannot be too highly estimated. It will redound to the untold good of this Territory, inasmuch as a measure of this character is well calculated to direct the world's attention to a very important section of country that to the present time has passed largely unnoticed. It will be the means of centering on Montana the attention of thousands heretofore comparatively uninformed of a Territory abounding in such resources of mines and of agriculture and of wonderland as we can boast, spread everywhere about us. The efficacy to this people of having in Congress a Delegate able, active, zealous and untiring in his labors, as well as in political harmony with the General Government, [58] is being amply demonstrated in the success attending the representative stewardship of Mr. Clagett. Our Delegate, surely is performing deeds in the interest of his constituents which none of them can gainsay or overlook, and those deeds are being recorded to his credit in the public's great ledger and in the hearts of us all.

On the following day, the New York Times commented in a broader vein, and without the partisan tootling:

It is a satisfaction to know that the Yellowstone Park bill has passed the House. Our readers have been made well acquainted with the beautiful and astonishing features of a region unlike any other in the world; and will approve the policy by which, while the title is still vested in the United States, provision has been made to retain it perpetually for the nation. The Yosemite Valley was similarly appropriated to public use some years back, and that magnificent spot was thus saved from possible defacement or other unseemly treatment that might have attended its remaining in private hands. . . . The new National Park lies in two Territories, Montana and Wyoming, but the jurisdiction of the soil, by the passage of the bill, remains forever with the Federal Government. In this respect the position of the Yellowstone Park differs from that of the Yosemite; since the latter was granted by Government to the State of California on certain conditions one of which excludes the local control of the United States; while the former will always be within that control.

Perhaps, no scenery in the world surpasses for sublimity that of the Yellowstone Valley; and certainly no region anywhere is so rich, in the same space, in wonderful natural curiosities. In addition to this, from the height of the land, and the salubrity of the atmosphere, physicians are of opinion that the Yellowstone Park will become a valuable resort for certain classes of invalids; and in all probability it will soon appear that the mineral springs, with which the place abounds, possess various curative powers. It is far from unlikely that the park may become in a few years the Baden or Homburg of America, and that strangers may flock thither from all parts of the world to drink the waters, and gaze on picturesque splendors only to be seen in the heart of the American Continent. [59]

The Yellowstone Park Act had the approval of President Ulysses S. Grant, who signed it into law on March 1, 1872. [60] The text of the act follows:

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled,

That the tract of land in the Territories of Montana and Wyoming lying near the head-waters of the Yellowstone River, and described as follows, to wit, commencing at the junction of Gardiner's River with the Yellowstone River, and running east to the meridian passing ten miles to the eastward of the most eastern point of—Yellowstone lake; thence south along said meridian to the parallel of latitude passing ten miles south of the most southern point of Yellowstone Lake; thence west along said parallel to the meridian passing fifteen miles west of the most western point of Madison Lake; thence north along said meridian to the latitude of the junction of the Yellowstone and Gardiner's Rivers; thence east to the place of beginning is hereby reserved and withdrawn from settlement, occupancy, or sale under the laws of the United States, and dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people; and all persons who shall locate or settle upon or occupy the same, or any part thereof, except as hereinafter provided, shall be considered trespassers, and removed therefrom.

SEC. 2. That said public park shall be tinder the exclusive control of the Secretary of the Interior, whose duty it shall be, as soon as practicable, to make and publish such rules and regulations as he may deem necessary or proper for the care and management of the same. Such regulations shall provide for the preservation, from injury or spoliation, or all timber, mineral deposits, natural curiosities, or wonders within said park, and their retention in their natural condition. The Secretary may, in his discretion, grant leases for building purposes for terms not exceeding ten years, of small parcels of ground, at such places in said park as shall require the erection of buildings for the accommodation of visitors; all of the proceeds of said leases, and all other revenues that may be derived from any source connected with said park, to be expended under his direction in the management of the same, and the construction of roads and bridle-paths therein. He shall provide against the wanton destruction of the fish and game found within said park, and against their capture or destruction for the purposes of merchandise or profit. He shall also cause all persons trespassing upon the same after the passage of this act to be removed therefrom, and generally shall be authorized to take all such measures as shall be necessary or proper to fully carry out the objects and purposes of this act. [61]

The new park was received with mixed emotions in Montana. Helena's Rocky Mountain Gazette, which had previously expressed a fear that the park legislation would remand the Yellowstone region into "perpetual solitude," stated:

In our opinion, the effect of this measure will be to keep the country a wilderness, and shut out, for many years, the travel that would seek that curious region if good roads were opened through it and hotels built therein. We regard the passage of the act as a great blow struck at the prosperity of the towns of Bozeman and Virginia City, which might naturally look for considerable travel to this section, if it were thrown open to a curious but comfort-loving public. [62]

The sarcastic reply of the Herald turned the controversy into a political mud-slinging contest, with the only sensible comments coming from other newspapers. The Bozeman Avant Courier sided with the Gazette in the matter of the settler's interests in the new park, stating, in regard to the setting aside of the area, "we were certainly under the impression that, in ease such was done, ample provision would be made in the bill for opening up the country by making good roads and establishment of hotels and other accomodations," adding, "unless some such provisions are yet incorporated in the bill by amendment, we agree with the Gazette, that it would have been better to have left its development open to the enterprising pioneers, who had already commenced the work." [63]

The Deer Lodge New North-West preferred to remain on neutral ground, reminding the contending editors that, as the settlers upon park lands were really residents of Wyoming Territory, "we are unable to see how it [reservation] will damage citizens of this Territory." Attention was also called to another largely overlooked fact: that regardless of the act setting aside the Yellowstone region, such settlers "are of course trespassers against the General Government, as all persons who reside upon unsurveyed public lands not mineral." [64]

A more enlightened view of the accomplishment in setting aside the Yellowstone region "for the benefit and enjoyment of the people" came from an eastern magazine, which noted:

It is the general principle which is chiefly commendable in the act of Congress setting aside the Yellowstone region as a national park. It will help confirm the national possession of the Yo Semite, and may in time lead us to rescue Niagara from its present degrading surroundings. That the park will not very soon be accessible to the public needs no demonstration. [65]

Those words foretold both the greatness of Yellowstone National Park, as the pilot model for a system of Federal parks, and the travail of its early years. At the moment, Americans were pleased with their new playground, and a few were also undismayed at its remoteness. Even as the organic act was being signed into law, the first visitors of that throng which swelled to more than 48 million persons in the first century were outfitting at the town of Bozeman for their park trip. [66] As a nation, we had come to realize a very important fact, which the New York Herald expressed this way:

Why should we go to Switzerland to see mountains, or to Iceland for geysers? Thirty years ago the attraction of America to the foreign mind was Niagara Falls. Now we have attractions which diminish Niagara into an ordinary exhibition. The Yo Semite, which the nation has made a park, the Rocky mountains and their singular parks, the canyons of the Colorado, the Dalles of the Columbia, the giant trees, the lake country of Minnesota, the country of the Yellowstone, with their beauty, their splendor, their extraordinary and sometimes terrible manifestations of nature, form a series of attractions possessed by no other nation in the world. [67]

|

|

Last Modified: Tues, Jul 4 2000 07:08:48 am PDT

haines/part3.htm