|

Yellowstone National Park: Its Exploration and Establishment Part I: Early Knowledge |

|

|

|

A fragmentary knowledge of the Yellowstone region was recorded by the explorers, trappers, missionaries, and prospectors of the period from 1805 to 1869. Such information was often discredited, yet provided the enticement for more fruitful exploration.

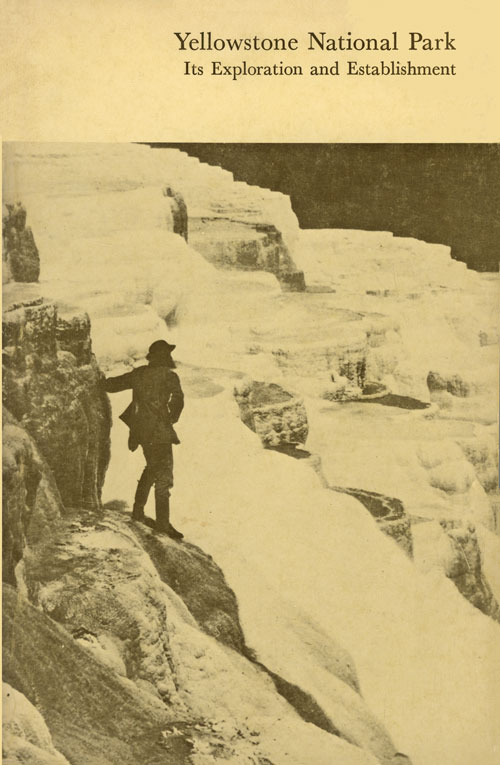

Giant Geyser, 1902, by William

Henry Jackson.

(Yellowstone National Park)

The records presently available indicate it was during this period that white men first became aware of the thermal features of the Yellowstone region. With our purchase of Louisiana from France on April 11, 1803, the way was open for official, semiofficial, and private exploration of the western reaches of that vast territory, and such ventures were immediately organized. Chief among these was the party led across the almost unknown West, from St. Louis to the mouth of the Columbia River and back, by Captains Lewis and Clark in 1804-06; and yet, despite the great interest of those explorers in the geography, geology, anthropology, and natural history of the country they traversed, the first notice of something unusual on the headwaters of the Yellowstone River did not come from them.

Instead, it appeared in a letter addressed to the Secretary of War on September 8, 1805, by Gov. James Wilkinson of Louisiana Territory, who included the following:

I have equipt a Perogue out of my Small private means, not with any view to Self interest, to ascend the missouri and enter the River Piere jaune, or yellow Stone, called by the natives, Unicorn River, the same by which Capt. Lewis I since find expects to return and which my informants tell me is filled with wonders, this Party will not get back before the Summer of 1807—they are natives of this Town, and are just able to give us course and distance, with the names and population of the Indian nations and bring back with them Specimens of the natural products . . . . [1]

Nothing further is known of the expedition Governor Wilkinson claims to have sent out; however, he soon obtained additional information from Indian sources in the form of a map drawn on a buffalo pelt. This delineation of the Missouri River and its southwestern headwaters was forwarded to President Thomas Jefferson on October 22, 1805, with a letter stating:

The Bearer hereof Capt. Amos Stoddard, who conducts the Indian deputation on their visit to you, has charge of a few natural productions of this Territory, to amuse a liesure Moment, and also a Savage delineation on a Buffaloe Pelt, of the Missouri & its South Western Branches, including the Rivers plate and lycorne or Pierre jaune; This Rude Sketch without Scale or Compass "et remplie de Fantaisies ridicules" is not destitute of Interests, as it exposes the location of several important Objects, & may point the way to useful enquiry—among other things a little incredible, a Volcano is distinctly described on Yellow Stone River . . . . [2]

At some time following its arrival at Washington on December 26, the buffalo-pelt map was placed in the entrance hall of President Jefferson's Virginia home, Monticello. [3] George Ticknor, who visited Monticello in February 1815, mentions this map in his description of the Hall, noting: "On the fourth side, in odd union with a fine painting of the Repentance of Saint Peter, is an Indian map on leather, of the southern waters of the Missouri, and an Indian representation of a bloody battle, handed down in their tradition." [4] It is the opinion of the leading Jeffersonian scholar that the map was transferred to the University of Virginia where it was probably burned when the Rotunda was destroyed by fire. [5]

The Lewis and Clark Expedition passed close to the Yellowstone region with no evident awareness of the thermal features hidden there. Indeed, the description of the Yellowstone River which was subsequently published is geographically vague; [6] however, some information concerning the thermal features of the region was obtained later. In Codex N, of the original journals of the expedition, there are entries which Thwaites believes were added on blank pages by William Clark after his return to St. Louis (probably after 1809). Under the heading, "Notes of Information I believe Correct," he makes this statement about the country south of the "Rochejone":

At the head of this river the nativs give an account that there is frequently herd a loud noise, like Thunder, which makes the earth Tremble, they State that they seldom go there because their children Cannot sleep—and Conceive it possessed of spirits, who were averse that men Should be near them. [7]

Additional information which came to Clark after the return of the expedition was entered upon a manuscript map he continued to amend for a half-dozen years as reports were received from fur traders who had pushed into the wilderness. [8] One of these was John Colter, a former member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition who remained in the mountains, and, later, while an employee of Manuel Lisa, made an epic winter journey which took him through the Yellowstone region. Something of what Colter saw was passed on to William Clark, who was thus enabled to chart several features of that terra incognita.

Lake Biddle (Jackson), Eustis Lake (Yellowstone), and the "Hot Spring Brimstone" shown near the crossing of "Colters rout" over the Yellowstone River are landmarks which confirm John Colter's passage, in 1807-08, through what is now Yellowstone National Park, and his discovery of at least one of its thermal areas. The identification of the latter can be made with reasonable assurance because of the proximity of Clark's notation to the crossing. The ford opposite Tower Fall, where the Bannock Indian trail (an aboriginal thoroughfare connecting the plains of central Idaho with the Yellowstone Valley and the Wyoming Basin) crossed the river, is the only place for many miles in either direction where a man traveling afoot could cross that stream—and then only during the low water of late fall and winter. This crossing is made at the "Sulphur Beds," which, together with the Calcite Springs a short distance downstream, make the locality sufficiently noisome to warrant the use of the term brimstone in its description.

Clark's manuscript map (map 1.) of the Yellowstone features deserves some notice. The relative sizes of the two lakes are reasonably correct, as portrayed, and the outline of Eustis will pass for that of Lake Yellowstone with its prominent indentations rounded-off; also, the distances—from Biddle to the southern shore of Eustis, and from the outlet of the latter to Colter's crossing of Yellowstone River—are acceptable. [9] However, the reasonableness of Clark's cartography was lost in the engraving Samuel Lewis made from the manuscript map. His map, [10] which was the one published in 1814 with the History cited in note 6, showed Lakes Biddle and Eustis as nearly equal in size, changing the outlet of the latter to its southern extremity and giving it the elongated shape which was characteristic of most map presentations for a half-century thereafter (map 2).

This is the place to mention what appears to be an unwarranted attempt to substantiate the presence of John Colter in the Yellowstone region. In regard to this supposed discovery, Phillip A. Rollins is quoted as follows:

In September of 1889, Tazewell Woody (Theodore Roosevelt's hunting guide), John H. Dewing (also a hunting guide), and I, found on the left side of Coulter Creek, some fifty feet from the water and about three quarters of a mile above the creek's mouth, a large pine tree on which was a deeply indented blaze, which after being cleared of sap and loose bark was found to consist of a cross thus 'X' (some five inches in height), and, under it, the initials 'JC' (each some four inches in height).

The blaze appeared to these training hunting guides, so they stated to me, to be approximately eighty years old.

They refused to fell the tree and so obtain the exact age of the blaze because they said they guessed the blaze had been made by Colter himself.

The find was reported to the Government authorities, and the tree was cut down by them in 1889 or 1890, in order that the blazed section might be installed in a museum, but as I was told in the autumn of 1890 by the then superintendent of the Yellowstone Park, the blazed section had been lost in transit. [11]

It seems more likely that the blaze Rollins found was related to the naming of the nearby stream. Coulter Creek, which flows into Snake River near the south boundary of the park, was named for John Merle Coulter, a botanist with the Hayden Survey, because of an amusing incident which occurred there. One of Dr. Coulter's students at the University of Chicago, where he taught botany in later years, kindly furnished the park with the eminent botanist's own version of the event, as recorded in a classroom notebook in 1922. The student says:

Dr. Coulter was fishing one day on the bank of a stream when he felt a slap on the shoulder and turned expecting to see one of his companions, but there was a large, black bear. Coulter plunged in and swam across the stream, then looking around saw that the bear had not followed, but was back there grinning at him. The party called this stream Coulter Creek, a name it still bears. [12]

Thermal pool, 1902, by William

Henry Jackson.

(Yellowstone National Park)

The onset of the War of 1812 put an end to the activity of American fur traders in the West before they were able to ransack such remote areas as the Yellowstone region, and, following that conflict, the better-organized British concerns monopolized the trade in the northern Rocky Mountains for a few years. Their advantage lay in the adoption of a method of trapping based upon the use of roving brigades of engagees—mainly Iroquois and French Canadians who did not have to wait at established trading posts for Indians to bring in the furs, as the Americans did. After 1821, the latter began to use similar tactics and soon took over the fur trade of the far West entirely.

A brigade of North West Co. men operating under Donald McKenzie came within sight of the Teton Range in 1818, and Alexander Ross, who was their scribe, mentions that "Boiling fountains having different degrees of temperature were very numerous; one or two were so very hot as to boil meat." [13] They may have been in the Yellowstone region, but the failure to mention landmarks makes that uncertain.

There was a visitor the following year who is known only by the initials "J. O. R." carved into the base of a pine tree, over the date "AUG. 29. 1819." [14] Superintendent Philetus W. Norris, who found this evidence of white penetration of the Yellowstone wilderness, has described it thus:

The next earliest evidence of white men in the Park [Colter's primacy had just been discussed], of which I have any knowledge, was discovered by myself at our camp in the little glen, where our bridle-path from the lake makes its last approach to the rapids, one-fourth of a mile above the upper falls. About breast-high upon the west side of a smooth pine tree, about 20 inches in diameter, were found, legibly carved through the bark, and not materially obliterated by overgrowth or decay, in Roman capitals and Arabic numerals, the following record:

J.O.R.

AUG. 29, 1819The camp was soon in excitement, the members of our party developing a marked diversity of opinion as to the real age of the record, the most experienced favoring the theory that it was really made at the date as represented. Upon the other side of this tree were several small wooden pins, such as were formerly often used in fastening wolverine and other skins while drying (of the actual age of which there was no clew further than they that were very old), but there were certain hatchet hacks near the record, which all agreed were of the same age, and that by cutting them out and counting the layers or annual growths the question should be decided. This was done, and although the layers were unusually thin, they were mainly distinct, and, in the minds of all present, decisive; and as this was upon the 29th day of July [1881], it was only one month short of sixty-two years since some unknown white man had there stood and recorded his visit to the roaring rapids of the "Mystic River," before the birth of any of the band of stalwart but bronzed and grizzled mountaineers who were then grouped around it. This is all which was then or subsequently learned, or perhaps ever will be, of the maker of the record, unless a search which is now in progress results in proving these initials to be those of some early rover of these regions. Prominent among these was a famous Hudson Bay trapper, named Ross. . . . The "R" in the record suggests, rather than proves, identity, which, if established, would be important, as confirming the reality of the legendary visits of the Hudson Bay trappers to the Park at that early day. Thorough search of the grove in which this tree is situated only proved that it was a long abandoned camping ground. Our intelligent, observant mountaineer comrade, Phelps, upon this, as upon previous and subsequent occasions, favored the oldest date claimed by any one, of the traces of men, and, as usual, proved to be correct. [15]

Superintendent Norris never did find out who J. O. R. was, though it now appears they may have lived in the same State. About the turn of the century, a writer who was assisting Olin D. Wheeler with the preparation of Northern Pacific Railroad publicity had an opportunity to interview an aged Frenchman by the name of Roch who lived at Luddington, Mich. In recalling that interview after a lapse of more than 30 years, Mr. Decker wrote:

He claimed to be over a hundred years old. I met his son at the same time, who was then seventy-five years old. He said his father was between a hundred and a hundred and nine years of age. In my interview with him, he said he went to the Park when a young man as hunter for a fur company, and he spoke of a tree that was marked and dated, and he said it would probably be found by somebody. . . . As near as I can get it, Mr. Roch was in the Park in 1818. [16]

Alexander Ross, the man Norris thought might have been J. O. R. (an unlikely presumption considering the dissimilarity of the first initials), returned to the Missouri headwaters in 1824 as the leader of a brigade of Hudson Bay Co. trappers. Agnes Laut examined the foolscap folios which made up his official report to the company, and she summarizes the activity of the brigade thus:

One week, the men were spread out in different parties on the Three Forks of the Missouri. Another week they were on the headwaters of the Yellowstone in the National Park of Wyoming. They did not go eastward beyond sight of the mountains but swung back and forward between Montana and Wyoming. [17]

Mrs. Laut copied a passage from that as-yet-unpublished report which hints that Ross' brigade was among the great geysers of the Yellowstone: "Saturday 24th [April, 1824]—we crossed beyond the Boiling Fountains. The snow is knee-deep half the people are snowblind from sun glare."

The record of British trapping activity in the Yellowstone region is admittedly sketchy, and all that can be added to it is the surmise of Superintendent Norris that the cache of iron traps found near Obsidian Cliff by his workmen, during the construction of the Norris road, was made by Hudson's Bay Co. men more than 50 years earlier. [18]

Just when American trappers began taking fur on the Yellowstone Plateau is uncertain. An exploration by Jedediah S. Smith and six unidentified trappers, northward from Green River in 1824, seems to have gotten no closer than Jackson's Hole and Conant Pass; [19] however, they definitely were there in 1826. A letter written to a brother in Philadelphia by one of the young men who went to the Rocky Mountains with General Ashley's expedition in 1822 contains the first clear description of Yellowstone features, and that portion is presented here just as written by Daniel T. Potts:

At or near this place heads the Luchkadee or Californ [Green River] Stinking fork [Shoshone River] Yellow-Stone South fork of Masuri and Henrys fork all those head at an angular point that of the Yellow-Stone has a large fresh water Lake near its head on the very top of the Mountain which is about one hundred by fourty Miles in diameter and as clear as Crystal on the South borders of this Lake is a number of hot and boiling springs some of water and others of most beautiful fine clay and resembles that of a mush pot and throws its particles to the immense height of from twenty to thirty feet in height The Clay is white and of a pink and water appears fathomless as it appears to be entirely hollow under neath. There is also a number of places where the pure suphor is sent forth in abundance one of our men Visited one of those wilst taking his recreation there at an instan the earth began a tremendious trembling and he with dificulty made his escape when an explosion took place resembling that of thunder. During our stay in that quarter I heard it every day. From this place by a circutous rout to the Nourth west we returned. [20]

Daniel T. Potts continued in the fur trade until the fall of 1828, when he went to Texas and began buying cattle for shipment to the New Orleans market. It has been presumed that he died soon afterward in the foundering of a cattle boat in the Gulf of Mexico. The Potts Hot Spring Basin on the shore of West Thumb Bay has been named for this trapper whose rude but very recognizable description of Yellowstone features was the first to appear in print.

During the period 1827 to 1833 American trappers are reported as having visited the Yellowstone region every year; [21] however, only the visit of Joseph L. Meek in 1829 can be documented. According to the reminiscence Mrs. Frances F. Victor obtained from the aged trapper about 1868, Joe was a novice of only 7 months experience with the firm of Smith, Jackson & Sublette when he approached the Yellowstone region from the north with a party led by William Sublette. They had crossed the mountains which lie between the West Fork of Gallatin River and the Yellowstone Valley and were resting their horses in the latter, near the Devils Slide, when they were suddenly attacked by a Blackfoot war party. Two men were killed and the trappers were scattered with the loss of most of their horses and equipment.

The 19-year-old recruit escaped across the Yellowstone River with only his mule, blanket, and gun, making his way southward into what is now Yellowstone National Park where, 5 days later, he

... ascended a low mountain in the neighborhood of his camp—and behold! the whole country beyond was smoking with the vapor from boiling springs, and burning with gasses, issuing from small' craters, each of which was emitting a sharp whistling sound. When the first surprise of this astonishing scene had passed, Joe began to ad mire its effect in an artistic point of view. The morning being clear, with a sharp frost, he thought himself reminded of the city of Pittsburg, as he had beheld it on a winter morning a couple of years before. This, however, related only to the rising smoke and vapor; for the extent of the volcanic region was immense, reaching far out of sight. The general face of the country was smooth and rolling, being a level plain, dotted with cone-shaped mounds. On the summits of these mounds were small craters from four to eight feet in diameter. Interspersed among these, on the level plain, were larger craters, some of them from four to six miles across. Out of these craters issued blue flames and molten brimstone.

For some minutes Joe gazed and wondered. Curious thoughts came into his head, about hell and the day of doom. With that natural tendency to reckless gayety and humorous absurdities which some temperaments are sensible of in times of great excitement, he began to soliloquize. Said he, to himself, "I have been told the sun would be blown out, and the earth burnt up. If this infernal wind keeps up, I shouldn't be surprized if the sun war blown out. If the earth is not burning up over thar, then it is that place the old Methodist preacher used to threaten me with. Any way it suits me to go and see what it's like."

On descending to the plain described, the earth was found to have a hollow sound, and seemed threatening to break through. But Joe found the warmth of the place most delightful, after the freezing cold of the mountains, and remarked to himself again, that "if it war hell, it war a more agreeable climate than he had been in for some time." [22]

Of course, there is no Yellowstone thermal area even remotely resembling Meek's description—a fact which caused historian Chittenden to admit the necessity for "making some allowance for the trapper's tendency to exaggeration;" and yet, he probably did blunder into the Norris Geyser Basin. Such a traumatic experience as he had undergone (a wild flight from a scene of butchery, into a wilderness where he even lost his mule), is liable to leave larger-than-life impressions upon a stripling mind. Fortunately for Joe, he was found by two experienced trappers sent out by Captain Sublette to track down the fugitives.

Two of the shadowy forays into the Yellowstone region during this period deserve a mention because of their consequences. One is the venture through which Johnson Gardner's name became attached to a beautiful mountain valley at the head of the river in Yellowstone National Park which now immortalizes him. Records kept at Fort Union, a fur post at the mouth of the Yellowstone River, indicate that it was probably in the fall of 1831 or the spring of 1832 when that illiterate, often brutal, trapper discovered the valley known thereafter among his peers as "Gardner's Hole," [24] and the place-name which now identifies the river flowing from that vale is the second oldest in Yellowstone Park—only the name Yellowstone having an earlier origin.

The other barely known visit which is of great importance through discovery of the great geysers of the Firehole River basins was that of a party of trappers led there by Manuel Alvarez in 1833.25 The stories told by these men at the annual rendezvous determined a clerk of the American Fur Co.—Warren Angus Ferris—to make an excursion to the geysers at the opening of the next summer season. Of this visit, which made him the first Yellowstone "tourist" (because his motive was curiosity, rather than business), he says:

I had heard in the summer of 1833, while at rendezvous, that remarkable boiling springs had been discovered on the sources of the Madison, by a party of trappers, in their spring hunt; of which the accounts they gave, were so very astonishing, that I determined to examine them myself, before recording their description, though I had the united testimony of more than twenty men on the subject, all declared they saw them, and that they really were as extensive and remarkable as they had been described. Having now an opportunity of paying them a visit, and as another or better might not soon occur, I parted with the company after supper, and taking with me two Pen-d'orielles, (who were induced to make the excursion with me, by the promise of an extra present,) set out at a round pace, the night being clear and comfortable. We proceeded over the plain about twenty miles, and halted until day-light, on a fine spring, flowing into Cammas Creek. Refreshed by a few hour's sleep, we started again after a hasty breakfast, and entered a very extensive forest, called the Piny Woods; (a continuous succession of low mountains or hills, entirely covered by a dense growth of this species of timber;) which we passed through, and reached the vicinity of the springs about dark, having seen several small lakes or ponds on the sources of the Madison, [26] and rode about forty miles; which was a hard day's ride, taking into consideration the rough irregularity of the country through which we had travelled.

We regaled ourselves with a cup of coffee, the materials for making which, we had brought with us, and immediately after supper, lay down to rest, sleepy and much fatigued. The continual roaring of the springs, however, (which was distinctly heard,) for some time prevented my going to sleep, and excited an impatient curiosity to examine them, which I was obliged to defer the gratification of, until morning, and filled my slumbers with visions of waterspouts, cataracts, fountains, jets d'eau of immense dimensions, etc. etc.

When I arose in the morning, clouds of vapour seemed like a dense fog to overhang the springs, from which frequent reports or explosions of different loudness, constantly assailed our ears. I immediately proceeded to inspect them, and might have exclaimed with the Queen of Sheba, when their full reality of dimensions and novelty burst upon my view, "the half was not told me."

From the surface of a rocky plain or table, burst forth columns of water of various dimensions, projected high in the air, accompanied by loud explosions, and sulphurous vapors, which were highly disagreeable to the smell. The rock from which these springs burst forth, was calcareous, [27] and probably extends some distance from them, beneath the soil. The largest of these wonderful fountains, projects a column of boiling water several feet in diameter, to the height of more than one hundred and fifty feet, in my opinion; but the party of Alvarez, who discovered it, persist in declaring that it could not be less than four times that distance in height—accompanied with a tremendous noise. These explosions and discharges occur at intervals of about two hours. [28] After having witnessed three of them, I ventured near enough to put my hand into the water of its basin, but withdrew it instantly, for the heat of the water in this immense chauldron [sic], was altogether too great for my comfort; and the agitation of the water, the disagreeable effluvium continually exuding, and the hollow unearthly rumbling under the rock on which I stood, so ill accorded with my notions of personal safety, that I retreated back precipitately, to a respectful distance. The Indians, who were with me, were quite appalled, and could not by any means be induced to approach them. They seemed astonished at my presumption, in advancing up to the large one, and when I safely returned, congratulated me on my "narrow escape." They believed them to be supernatural, and supposed them to be the production of the Evil Spirit. One of them remarked that hell, of which he had heard from the whites, must be in that vicinity. [29] The diameter of the basin into which the waters of the largest jet principally fall, and from the centre of which, through a hole in the rock of about nine or ten feet in diameter, the water spouts up as above related, may be about thirty feet. There are many other smaller fountains, that did not throw their water up so high, but occurred at shorter intervals. In some instances the volumes were projected obliquely upwards, and fell into the neighbouring fountains, or on the rock or prairie. But their ascent was generally perpendicular, falling in and about their own basins or apertures. These wonderful productions of nature, are situated near the centre of a small valley, surrounded by pine-crowned hills, through which a small fork of the Madison flows.

From several trappers who had recently returned from the Yellow Stone, I received an account of boiling springs, that differ from those seen on Salt river only in magnitude, being on a vastly larger scale; some of their cones are from twenty to thirty feet high, and forty to fifty paces in circumference. Those which have ceased to emit boiling, vapour, Etc., of which there were several, are full of shelving cavities, even some fathoms in extent, which give them, inside, an appearance of honey-comb. The ground for several acres extent in vicinity of the springs is evidently hollow, and constantly exhales a hot steam or vapour of disagreeable odour, and a character entirely to prevent vegetation. They are situated in the valley at the head of that river, near the lake, which constitutes its source. [30]

A short distance from these springs, near the margin of the lake, there is one quite different from any yet described. It is of a circular form, several feet in diameter, clear, cold and pure; the bottom appears visible to the eye and seems seven or eight feet below the surface of the earth or water, yet it has been sounded with a lodge pole fifteen feet in length, without meeting any resistance. What is most singular with respect to this fountain, is the fact that at regular intervals of about two minutes, a body or column of water bursts up to the height of eight feet, with an explosion as loud as the report of [a] musket, and then falls back into it; for a few seconds the water is roiley, but it speedily settles, and becomes transparent as before the efluxion. A slight tremulous motion of the water and a low rumbling sound from the caverns beneath, precede each explosion. This spring was believed to be connected with the lake by some subterranean passage, but the cause of its periodical eruptions or discharges, is entirely unknown. I have never before heard of a cold spring, whose waters exhibit the phenomena of periodical explosive propulsion, in form of a jet. [31] The geysers of Iceland, and the various other European springs, the waters of which are projected upwards, with violence and uniformity, as well as those seen on the head waters of the Madison, are invariably hot. [32]

A point worthy of notice, and one which gives the observations of Warren Angus Ferris a particular value, is the fact that he had been trained as a surveyor, and it was that occupation to which he devoted his life upon abandoning the fur trade in 1835.

The year Ferris left the mountains, the Yellowstone region was visited for the first time by a trapper who came to know the area well during the 9 years he spent in the northern Rocky Mountains; even more important, he left a reliable record of what he saw during those years, for he, too, was a competent journalist. [33] He was Osborne Russell, a Maine farm boy who joined Nathaniel J. Wyeth's Columbia River Fishing & Trading Co. in 1834, becoming a member of the garrison left at Fort Hall, on Snake River, that summer. It was from that isolated post that he went out the following March with a "spring hunt" intended to tap the fur-wealth of the Yellowstone region.

Because of their leader's poor knowledge of the country, the party Russell was with entered the confines of the present Yellowstone National Park by a difficult route which brought them onto the headwaters of Lamar River [34] from the North Fork of the Shoshone. Here is Russell's introduction to the Yellowstone country, as recorded in his manuscript:

[p. 33] 28th [July, 1835] We crossed the mountain in a West direction thro. the thick pines and fallen timber about 12 mls and encamped in a small prairie about a mile in circumference Thro. this valley ran a small stream in a north direction which all agreed in believing to be a branch of the Yellow Stone. 29th We descended the stream about 15 mls thro. the dense forest and at length came to a beautiful valley about 8 Mls. long and 3 or 4 wide [35] surrounded by dark and lofty mountains. The stream after running thro. the center in a NW direction rushed down a tremendous canyon of basaltic rock apparently just wide enough to admit its waters. The banks of the stream in the valley were low and skirted in many places with beautiful Cotton wood groves.

Here we found a few Snake Indians [36] comprising 6 men 7 women and 8 or 10 children who were the only Inhabitants of this lonely and secluded spot. They were all neatly clothed in dressed deer and Sheep skins of the best quality and seemed to be perfectly contented and happy. They were rather surprised at our approach and retreated to the heights where they might have a view of us without apprehending any danger, but having persuaded them of our pacific intentions we then succeeded in getting them to encamp with us. Their personal property consisted of one old butcher Knife nearly worn to the back two old shattered fusees which had long since become useless for want of ammunition a Small Stone pot and about 30 dogs on which they carried their skins, clothing, provisions etc on their hunting excursions. They were well armed with bows and arrows pointed with obsidian. The bows were beautifully wrought from Sheep, Buffaloe and Elk horns secured with Deer and Elk sinews and ornamented with porcupine quills and generally about 3 feet long. We obtained a large number [p. 34] of Elk Deer and Sheep skins from them of the finest quality and three large neatly dressed Panther Skins in return for awls axes kettles tobacco ammunition etc. They would throw the skins at our feet and say "give us whatever you please for them and we are satisfied. We can get plenty of Skins but we do not often see the Tibuboes" (or People of the Sun). They said there had been a great many beaver on the branches of this stream but they had killed nearly all of them and being ignorant of the value of fur had singed it off with fire in order to drip the meat more conveniently. They had seen some whites some years previous who had passed thro, the valley and left a horse behind but he had died during the first winter. They are never at a loss for fire which they produce by the friction of two pieces of wood which are rubbed together with a quick and steady motion. One of them drew a map of the country around us on a white Elk Skin with a piece of Charcoal after which he explained the direction of the different passes, streams etc. From them we discovered that it was about one days travel in a SW direction to the outlet or northern extremity of the Yellow Stone Lake, but the route from his description being difficult and Beaver comparatively scarce our leader gave out the idea of going to it this season as our horses were much jaded and their feet badly worn. Our Geographer also told us that this stream united with the Yellow Stone after leaving this Valley half a days travel in a west direction. The river then ran a long distance thro. a tremendous cut in the mountain in the same direction and emerged into a large plain the extent of which was beyond his geographical knowledge or conception.

Two days later this party continued down the Lamar River to the crossing of the Yellowstone, [37] where they laid over a day while a search was made for a hunter who failed to come into camp. Efforts to locate the lost man failing, the trappers continued westward over the Blacktail Deer Plateau to "Gardner's Hole," [38] where they stopped again. After trapping for more than 2 weeks in that beautiful mountain valley, the party crossed the Gallatin Range, onto the river which drains its western flank, and were soon out of present Yellowstone Park.

Osborne Russell entered the Yellowstone region the following summer with some of Jim Bridger's trappers, with whom he had joined after quitting the Columbia River Fishing & Trading Co. The route followed was the conventional one from Jackson's Hole to the upper Yellowstone River via Two Ocean Pass. Continuing from Russell's manuscript, he says:

[p. 53] 9th [August, 1836] . . . we came to a smooth prarie about 2 Mls long and half a Ml. wide lying east and west surrounded by pines. On the South side about midway of the prarie stands a high snowy peak from whence issues a [p. 54]. Stream of water which after entering the plain it divides equally one half running West and the other East thus bidding adieu to each other one bound for the Pacific and the other for the Atlantic ocean. [39] Here a trout of 12 inches in length may cross the mountains in safety. Poets have sung of the "meeting of the waters" and fish climbing cataracts but the "parting of the waters and fish crossing mountains" I believe remains unsung as yet by all except the solitary Trapper who sits under the shade of a spreading pine whistling blank-verse and beating time to the tune with a whip on his trap sack whilst musing on the parting advise of these waters.

From Two Ocean Pass, the trappers traveled down Atlantic Creek to the valley of the upper Yellowstone River, [40] which was followed to Yellowstone Lake. The trail then passed along the east shore of the lake to a pleasant camping place near the outlet. [41] While encamped there, Russell wrote this description of Lake Yellowstone and the hot springs at Steamboat Point:

[p. 55] The Lake is about 100 Mls. in circumference bordered on the East by high ranges of Mountains whose spurs terminate at the shore and on the west by a low bed of piney mountains its greatest width is about 15 Mls lying in an oblong form south to north or rather in the shape of a crescent. [42] Near where we encamped were several hot springs which boil perpetually. Near these was an opening in the ground about 8 inches in diameter from which steam issues continually with a noise similar to that made by the steam issuing from a safety valve of an engine and can be heard 5 or 6 Mls. distant. I should think the steam issued with sufficient force to work an engine of 30 horse power.

Osborne Russell and six other trappers separated from the main party and proceeded to the Lamar Valley by way of Pelican Creek. Enroute they camped in a grassy glen where elk ribs were broiled before a blazing fire, and afterward the evening hours were whiled away in storytelling. That this was only the preferred entertainment of men isolated for long periods from civilization and no reflection on their veracity, is made clear by Russell, who says:

[p. 56] The repast being over the jovial tale goes round the circle the peals of loud laughter break upon the stillness of the night which after being mimicked in the echo from rock to rock it dies away in the solitary glens. Every tale puts an auditor in mind of something similar to it but under different circumstances which being told the "laughing part" gives rise to increasing merriment and furnishes more subjects for good jokes and witty sayings such as Swift never dreamed of. Thus the evening passed with eating drinking and stories enlivened with witty humor until near Midnight all being wrapped in their blankets lying around the fire gradually falling to sleep one by one until the last tale is "encored" by the snoring of the drowsy audience.

After trapping 4 days in that "secluded valley" described by Russell the previous year, this small party continued to Gardners Hole where they rejoined Jim Bridger's camp and soon passed out of the Yellowstone mountains.

Osborne Russell came back to the Yellowstone region in 1837, entering it again by way of Two Ocean Pass—called the "Yellowstone Pass" by some trappers. This third visit followed the same general route as that of 1836 until the Lamar River was reached at a point somewhat south of the "secluded valley"; from there, they turned eastward, to the Hoodoo Basin, and then climbed over the Absaroka Range and out of the park area. After trapping for some time on the North Fork of the Shoshone River (the Stinkingwater River of an earlier day), Russell and his comrades crossed over to the Clark Fork above its great canyon and worked up that stream back into what is now Yellowstone Park. However, they did not tarry on the tributaries of the Lamar River but continued northward over the divide into the Boulder River drainage on September 13.

Osborne Russell went into the Yellowstone region for the last time in the summer of 1839—a visit which provided new sights and experiences. This time he entered the Yellowstone region directly up Snake River from Jackson Lake, very much as the South Entrance Road now does; however, his party passed around the west side of Lewis Lake, continuing up its inlet stream to Shoshone Lake. [43] At the west end of the lake they came upon "about 50 springs of boiling hot water," including at least one active geyser. [44] This "hour spring" was described thus by Russell:

[p. 120] the first thing that attracts the attention is a hole about 15 inches in diameter in which the water is boiling slowly about 4 inches below the surface at length it begins to boil and bubble violently and the water commences raising and shooting upwards until the column arises to the hight of sixty feet from whence it falls to the ground in drops on a circle of about 30 feet in diameter being perfetly cold when it strikes the ground. It continues shooting up in this manner five or six minutes [p. 121] and then sinks back to its former state of Slowly boiling for an hour and then shoots forth as before My Comrade Said he had watched the motions of this Spring for one whole day and part of the night the year previous and found no irregularity whatever in its movements. [45]

From the Shoshone Geyser Basin, Russell's party crossed the divide into the drainage of the Firehole River. They appear to have passed through the geyser basins without seeing a major geyser in action. The peculiarly sculptured cone of Lone Star Geyser was mentioned by Russell, and he was impressed with the convenience of cookery in the geyser basins, where the "kettle is always ready and boiling"; but only one feature of the wonder-filled area was described in detail. Of it he wrote:

[p. 122] At length we came to a boiling Lake about 300 ft in diameter forming nearly a complete circle as we approached on the South side. The steam which arose from it was of three distinct Colors from the west side for one third of the diameter it was white, in the middle it was pale red, and the remaining third on the east light sky blue [46]. Whether it was something peculiar in the state of the atmosphere the day being cloudy or whether it was some Chemical properties contained in the water which produced this phenomenon. I am unable to say and shall leave the explanation to some scientific tourist who may have the Curiosity to visit this place at some future period—The water was of deep indigo blue boiling like an imense cauldron running over the white rock which had formed [round] the edges to the height of 4 or 5 feet from the surface of the earth sloping gradually for 60 or 70 feet. What a field of speculation this presents for chemist and geologist.

From the Lower Geyser Basin, the trappers followed the Firehole River to its junction with the Gibbon—from which he identifies the "Burnt Hole" of the trappers as the present Madison Valley [47]—and then turned eastward into Hayden Valley. After nearly 6 weeks of trapping in familiar country northeast of Yellowstone Lake, the party was encamped on its northern shore when surprised by Blackfoot Indians, who despoiled them. [48] Left destitute, and with himself and another wounded, Russell and his two remaining comrades managed to make their way out of the present park area by passing around the west shore of Lake Yellowstone, crossing over to Heart Lake and down its outlet stream and Snake River. They then made their way across the Teton Range by the Conant Pass and onto the Snake River Plain, where they ultimately found succor at Fort Hall. Though Russell never went back to the Yellowstone region, he had seen enough of it to write the most comprehensive account of that wilderness extant prior to definitive exploration.

Another party of trappers met Blackfoot Indians near Pelican Creek that fall and the resulting battle appears to have been a particularly sanguinary affair. All that is known of this collision comes from "Wild Cat Bill" Hamilton, a trapper who was not a participant but had this story from men he knew well:

In the year 1839 a party of forty men started on an expedition up the Snake River. In the party were Ducharme, [49]Louis Anderson, Jim and John Baker, Joe Power, L'Humphrie, and others. They passed Jackson's Lake, catching many beaver, and crossed the Continental Divide, following down the Upper Yellowstone—Elk [50]—River to the Yellowstone Lake. They described accurately the Lake, the hot springs at the upper end of the lake; Steamboat Springs on the south side; the lower end of the lake, Vinegar Creek, and Pelican Creek, where they caught large quantities of beaver and otter. They also told about the sulphur mountains, and the Yellowstone Falls, and the mud geysers . . . .

They also described a fight that they had with a large party of Piegan Indians at the lower end of the lake on the north side, and on a prairie of about half a mile in length. The trappers built a corral at the upper end of the prairie and fought desperately for two days, losing five men besides having many wounded. The trappers finally compelled the Piegans to leave, with the loss of many of their bravest warriors. After the wounded were able to travel, they took up an Indian trail and struck a warm-spring creek. This they followed to the Madison River, which at that time was not known to the trappers. [51]

The trappers of the fur trade days were not entirely oblivious to the value of their geographical discoveries. Ferris prepared a manuscript map in 1836 which showed his extensive, and essentially correct, knowledge of the physiography of the northern Rocky Mountains—of interest here because of its notations, "Boiling water volcanoes" southwest of Yellowstone Lake and "Spouting Fountains" on the headwaters of the Madison River (the latter vaguely included within the dashed line enclosing a "Burnt Hole"). However, this map did not influence the cartography of the fur trade era because it remained in the hands of its author and his heirs. [52]

The information attributed to "William Sublette and others," [53] which appears on a map prepared by Capt. Washington Hood, of the Corps of Topographical Engineers, in 1839, was more useful. In addition to "Yellowstone L." and "Burnt Hole," this excellently drawn map showed a "Yellowstone Pass" (Two Ocean Pass) south of the lake, and a "Gardner's Fork" emptying into Yellowstone River north of the lake. But, most interestingly, the drainage of Gardner River bears the notations "Boiling Spring" and "White Sulphur Banks," the latter being an obvious allusion to the Mammoth Hot Springs. [54] (See map 3.)

William Sublette, the fur trader who provided much of the information for Captain Hood's map, is said to have guided the Scottish sportsman, Sir William Drummond Stewart, through the Yellowstone region in 1843—a visit recalled in the words of a young gentleman of St. Louis, who was a member of that party. He says:

. . . we reached a country that seemed, indeed, to be Nature's wonderworld. The rugged grandeur of the landscape was most impressive, and the beauty of the crystal-clear water falling over huge rocks was a picture to carry forever in one's mind. Here was an ideal spot to camp; so we broke ranks and settled down to our first night's rest in the region now known as Yellowstone National Park.

On approaching, we had noticed at regular intervals of about five or ten minutes what seemed to be a tall column of smoke or steam, such as would arise from a steamboat. On nearer approach, however, we discovered it to be a geyser, which we christened "Steam Boat Geyser." Several other geysers were found near by, some of them so hot that we boiled our bacon in them, as well as the fine speckled trout which we caught in the surrounding streams. One geyser, a soda spring, was so effervescent that I believe the syrup to be the only thing lacking to make it equal a giant ice cream soda of the kind now popular at a drugstore. We tried some experiments with our first discovery by packing it down with armfuls of grass; then we placed a flat stone on top of that, on which four of us, joining hands, stood in a vain attempt to hold it down. In spite of our efforts to curb Nature's most potent force, when the moment of necessity came, Old Steam Boat would literally rise to the occasion and throw us all high into the air, like so many feathers. It inspired one with great awe for the wonderful works of the Creator to think that this had been going on with the regularity of clockwork for thousands of years, and the thought of our being almost the first white men to see it did not lessen its effect. [55]

The improbability that four men could come away unscathed from such an attempt to throttle a major geyser, combined with the generally vague nature of the foregoing account, justifies a suspicion that it was created to entertain home folks, and only entered the realm of the historical through a daughter's desire to record her father's reminiscences. Thus, until such time as the Sublette-Stewart party s presence so far north of the Oregon Trail route as the Yellowstone region shall be confirmed, Kennerly's experiences there should be viewed with skepticism.

Three years later, James Gemmell—an old trapper known as "Uncle Jimmy" in Montana—passed through the Yellowstone region with Jim Bridger. Olin D. Wheeler, the eminent historian of the Northern Pacific Railway Co. and a dedicated Yellowstone buff, has recorded the visit thus:

Mr. Gemmell said: "In 1846 I started from Fort Bridger in company with old Jim Bridger on a trading expedition to the Crows and Sioux. We left in August with a large and complete outfit, went up Green River and camped for a time near the Three Tetons, and then followed the trail over the divide between Snake River and the streams which flow north into Yellowstone Lake. We camped for a time near the west arm of the lake and here Bridger proposed to show me the wonderful spouting springs on the head of Madison. Leaving our main camp, with a small and select party we took the trail by Snake Lake (now called Shoshone Lake) and visited what have of late years become so famous as the Upper and Lower Geyser Basins. There we spent a week and then returned to our camp, whence we resumed our journey, skirted the Yellowstone Lake along its west side, visited the Upper and Lower Falls, and the Mammoth Hot Springs, which appeared as wonderful to us as had the geysers. Here we camped several days to enjoy the baths and to recuperate our animals, for we had had hard work in getting around the lake and down the river, because of so much fallen timber which had to be removed. We then worked our way down the Yellowstone and camped again for a few days' rest on what is now the [Crow Indian] reservation, opposite to where Benson's landing now is. [56]

Yet another of these belated forays of trappers into the Yellowstone region has been recorded by Captain Topping in Chronicles of the Yellowstone. He says:

Kit Carson, Jim Bridger, Lou Anderson, Soos, and about twenty others on a prospecting trip, came from St. Louis, overland, to the Bannock Indian camp on Green River, late in the fall of 1849. They fixed up winter quarters and stayed with these Indians till spring. Then they went up the river and as soon as the snow permitted crossed the mountains to the Yellowstone and down it to the lake and falls; then across the divide to the Madison river. They saw the geysers of the lower basin and named the river that drains them the Fire Hole. Vague reports of this wonderful country had been made before. They had not been credited, but had been considered trapper's tales (more imagination than fact). The report of this party made quite a stir in St. Louis, and a party organized there the next winter to explore this country, but from some, now unknown, cause did not start. . . . The explorers went down the Madison till out of the mountains and then across the country to the Yellowstone. [57]

Whatever stir was created by the information brought back to St. Louis by this party, it left no lasting trace. However, those "trapper's tales," which were discredited in their own day, have proven very durable, and a few words about them are in order.

As Osborne Russell has clearly shown, storytelling was the principal form of entertainment among the illiterate and semiliterate men of the fur trade, [58] a proclivity which those who knew them understood and considered no reflection upon their veracity when speaking of serious matters. Capt. W. F. Raynolds, who was willing enough to have Jim Bridger for his guide in unexplored country, thought it was not at all surprising that such men "should beguile the monotony of camp life by 'spinning yarns' in which each tried to excell all others, and which were repeated so often and insisted upon so strenuously that the narrators came to believe them most religiously." [59]

The storytelling of Jim Bridger has been described by Capt. Eugene F. Ware, an artillerist stationed at Fort Laramie in 1864, whose statements have been combined as follows:

Major Bridger was a regular old Roman in actions and appearances, and he told stories in such a solemn and firm, convincing way that a person would be likely to believe him . . . One of the difficulties with him was that he would occasionally tell some wonderful story to a pilgrim, and would try to interest a new-coiner with a lot of statements which were ludicrous, sometimes greatly exaggerated, and sometimes imaginary. . . . He wasn't the egotistic liar that we so often find. He never in my presence vaunted himself about his own personal actions. He never told about how brave he was, nor how many Indians he had killed. His stories always had reference to some outdoor matter or circumstances . . . He had told each story so often that he had got it into language form, and told it literally alike. He had probably told them so often that he got to believing them himself. [60]

James Stevenson, who knew Jim Bridger well during the period 1859-60, thought Bridger's stories, as told by him, were uncouth. [61]

Of the seven stories about the Yellowstone region attributed to Jim Bridger, there is evidence indicating that four—or tales similar to them—were a part of his repertoire, while the others appear to be relatively recent literary accretions of the type Elbert Hubbard called "kabojolisms" (stories attributed to a person who did not tell them, in order to gain popular acceptance for them)—a process best typified as plagiarism in reverse.

The petrified forest story is one of the Yellowstone tales attributed to Jim Bridger. However, it is but a re-phrasing of a story Moses "Black" Harris put into circulation in 1823. A fellow trapper, James Clyman, noted in his diary that autumn:

A mountaineer named Harris being in St. Louis some years after [seeing the petrified trees] undertook to describe some of the strange things seen in the mountains, [and] spoke of this petrified grove, in a restaurant, where a caterer for one of the dailies was present; and the next morning his exaggerated statement came out saying a petrified forest was lately discovered where the tree branches, leaves and all, were perfect, and the small birds sitting on them, with their mouths open, singing at the time of their transformation to stone. [62]

A quarter-century later, this story was still being told, in an amplified form—and still attributed to trapper Harris; but the petrifactions were now located in the Black Hills and the year had been advanced to 1833. [63] Undoubtedly, Jim Bridger was aware of that persistent tale almost from its origin, but he is not identified with it—as a narrator—until 1859. In that and the following year he served as a guide for the Raynolds expedition to the headwaters of the Yellowstone River, and, while in that service, he told some of those "Munchausen tales," which Captain Raynolds thought "altogether too good to be lost." That officer recorded a petrified prairie story (presumably Jim's) which goes thus:

In many parts of the country petrifactions and fossils are very numerous; and, as a consequence, it was claimed that in some locality (I was not able to fix it definitely) a large tract of sage is perfectly petrified, with all the leaves and branches in perfect condition, the general appearance of the plain being [not] unlike that of the rest of the country, but all is stone, while the rabbits, sage hens, and other animals usually found in such localites are still there, perfectly petrified and as natural as when they were living; and more wonderful still, these petrified bushes bear the most wonderful fruit—diamonds, rubies, sapphires, emeralds, etc., etc., as large as black walnuts, are found in abundance. "I tell you, sir", said one narrator, "it is true, for I gathered a quart myself, and sent them down the country." [64]

Thus, the petrified forest story had, toward the end of its fourth decade, been generalized and divested of its specifics of time and place and was very likely a part of Bridger's repertoire. That he finally did turn that into a stock petrified forest story based on a Yellowstone feature seems probable from a second-hand tale told by General Nelson A. Miles in 1897. According to him,

. . . one night after supper, a comrade who in his travels had gone as far south as the Zuni Village, New Mexico, and had discovered the famous petrified forest of Arizona, inquired of Bridger:

"Jim, were you ever down to Zuni?"

"No, thar ain't no beaver down thar."

"But Jim, there are some things in this world besides beaver. I was down there last winter and saw great trees with limbs and bark all turned to stone."

"O," returned Jim, "that's peetrifaction. Come with me to the Yellowstone next summer, and I'll show you peetrified trees a-growing, with peetrified birds on 'em a-singing peetrified songs." [65]

Such a remark hardly justifies the additions Historian Chittenden made to this vague oral tradition of the trapping fraternity, where he poetically states: "Even flowers are blooming in colors of crystal, and birds soar with wings spread in motionless flight, while the air floats with music and perfume silicious, and the sun and the moon shine with petrified light!" [66]

In a similar manner, the glass mountain story which Bridger is credited with telling to tenderfeet along the emigrant road was altered to fit Obsidian Cliff in present Yellowstone Park. This we have on the authority of Superintendent Norris, who says:

So with his famous legend of a lake with millions of beaver nearly impossible to kill because of their superior cuteness; with haunts and houses in inaccessible grottoes in the base of a glistening mountain of glass, which every mountaineer of our party at once recognized as an exaggeration of the artificial lake [Beaver Lake] and obsidian mountain [Obsidian Cliff] which I this year discovered . . . . [68]

The other two authentic Bridger stories referring to the Yellowstone region are those concerning the stream-heated-by-friction and Hell-close-below. The former was recorded by Raynolds, [69] while we are indebted to Ware for the latter. [70] Several other tall tales concerned with the use of an echo as an alarm clock, the convenient suspension of gravity, and the shrinking ability of certain waters, have no traceable antecedents in fur trade days, and probably are of more recent origin.

Paint pots, 1902, by William

Henry Jackson.

(Yellowstone National Park)

Between the fur trade and prospecting eras is a brief period of missionary and military exploration which advanced the general knowledge of the Yellowstone region without any actual penetration of its fastnesses. Through their maps and writings these explorers became the means of preserving an important residual from that store of accurate geographical information amassed by the men of the fur trade. The fact that Jim Bridger provided most of the information set on paper by intelligent, perceptive men testifies to the good repute in which his serious utterances were held.

Bridger was present in 1851 at the great treaty council held at Fort Laramie to secure the emigrant road from Indian molestation, and, while there, he made a map for the Jesuit priest, Father Pierre-Jean DeSmet, which showed the streams heading in and around the Yellowstone region. [71] Bridger's remarkable map set the missionary-explorer straight on the rumors he had heard in 1839 concerning manifestations of volcanism on the headwaters of the Missouri River, [72] allowing him to add important details to his manuscript map. [73]

The Bridger map is essentially a hydrographic sketch of amazing accuracy when one accepts its lack of scale. Two Ocean Pass is indicated by the meeting of Atlantic and Pacific Creeks (both named), and the ultimate sources of the upper Yellowstone River are shown as originating on the flank of the Absaroka Range opposite Wind River. An oval Yellowstone Lake—unnamed but containing the notation "60 by 7"—has "Hot Springs" noted on its eastern shore (Steamboat Point) and "Volcano" near its outlet (Mud Geyser Area). The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone is indicated by a crinkled outline, with "Falls 250 Feet" at its upper end and a ford below—shown by a heavy pen stroke across the river. The Lamar River, marked "Meadow", is shown with its feeder streams nestled against the Absaroka Range, and north of it a short stream marked "Beaver" (Slough Creek) terminates in a lake (Abundance). The prominant leftward trend of the Yellowstone River from its junction with the Lamar is shown, and farther down the rightward swing, as the river turns back toward a north course, is indicated. "Gardener's Cr." is shown entering at the latter point, and on its west bank is a "Sulphur Mtn." (Mammoth Hot Springs).

The presentation of the "Madison" and "Gallatin" headwaters of the Missouri River suffers from being cramped. A mass of pen curls on both the southern and northern branches of the Madison appear to represent the Firehole and Norris thermal areas, with the notation "volcanic country" between them. Centered in the triangle formed by Yellowstone Lake, the mouth of Lamar River, and the head of Gibbon River is a circled notation "Great Volcanic Country 100 miles in extent." Of particular importance beyond the Yellowstone Plateau is the notation at the forks of the "Stinking River" (Shoshone): "Sulphur Springs Colter's Hell."

Such was Bridger's own delineation of the Yellowstone region, with names added by DeSmet (see map 4). Most of that information was transferred to DeSmet's manuscript map, but there are some changes and additions worthy of mention. At Two Ocean Pass, he added a short "Two Ocean Rv." (recognizable as Two Ocean Creek, the stream which flows from the mountains into the pass to split into Atlantic and Pacific creeks), and, on the upper Yellowstone River, he added a "Bridger's Lake & Riv." (both misplaced). The DeSmet manuscript map names Yellowstone Lake, retaining the notation concerning its size, but omits both the outline of the Grand Canyon and the reference to the falls at its upper end; however, a name—"Little Falls"—appears at just the right place to represent Tower Fall. Lamar River is mislabeled "Beaver Creek" (it was "Meadow" on Bridger's map), and the Slough Creek and Hellroaring drainages were omitted.

But it was in presenting the headwaters of the Madison River that DeSmet deviated most from Bridger's information. The eastward-trending branch is named "Fire Hole Riv.," while a southern branch, passing through two small lakes, is shown as "DeSmet's L. and Riv." This latter addition appears to portray the Lewis-Shoshone system, but with its river flowing to the Madison rather than Snake River (see map 5).

The changes which appear on DeSmet's manuscript map may represent additional information received in oral form from Bridger, or they may have come from an entirely different source, but the result was so much better than the best maps available to the Indian commissioners that he was asked to prepare a general map suitable for their purpose—an outcome which he explains thus:

When I was at the council ground in 1851, on the Platte River, at the mouth of Horse creek, I was requested by Colonel Mitchell to make a map of the whole Indian country, relating particularly to the Upper Missouri, the waters of the upper Platte, east of the Rocky mountains and of the headwaters of the Columbia and its tributaries west of these mountains. In compliance with this request I drew up the map from scraps then in my possession. The map, so prepared, was seemingly approved and made use of by the gentlemen assembled in council, and subsequently sent on to Washington together with the treaty then made with the Indians. [74]

In a letter written from the council grounds to his superiors, DeSmet describes the Yellowstone thermal features as follows: [75]

Near the source of the river Puante [Stinking Water, now called Shoshone] which empties into the Big Horn, and the sulphurous waters of which have probably the same medicinal qualities as the celebrated Blue Lick Springs of Kentucky, is a place called Colter's Hell—from a beaver hunter of that name. This locality is often agitated with subterranean fires. The sulphurous gases which escape in great volumes from the burning soil infect the atmosphere for several miles, and render the earth so barren that even the wild worm wood cannot grow on it. The beaver hunters have assured me that the frequent underground noises and explosions are frightful.

However, I think that the most extraordinary spot in this respect, and perhaps the most marvelous of all the northern half of this continent, is in the very heart of the Rocky Mountains, between the forty-third and forty-fifth degrees of latitude and 109th and 11th degrees of longitude, that is, between the sources of the Madison and Yellowstone. It reaches more than a hundred miles. Bituminous, sulphurous and boiling springs are very numerous in it. The hot springs contain a large quantity of calcareous matter [silicious], and form hills more or less elevated, which resemble in their nature, perhaps, if not in their extent, the famous springs of Pambuk Kalessi, in Asia Minor, so well described by Chandler [Richard Chandler, English Archaeologist, 1738-1810]. The earth is thrown up very high, and the influence of the elements causes it to take the most varied and the most fantastic shapes. Gas, vapor and smoke are continually escaping by a thousand openings, from the base to the summit of the volcanic pile; the noise at times resembles the steam let off by a boat. Strong subterranean explosions occur, like those in 'Colter's Hell'. The hunters and Indians speak of it with a superstitious fear, and consider it the abode of evil spirits, that is to say, a kind of hell. Indians seldom approach it without offering some sacrifice, or at least without presenting the calumet of peace to the turbulent spirits, that they may be propitious. They declare that the subterranean noises proceed from the forging of warlike weapons: each eruption of earth is, in their eyes, the result of a combat between the infernal spirits, and becomes a monument of a new victory or calamity. [76]

Near Gardiner river, a tributary of the Yellowstone, and in the vicinity of the region I have just been describing, there is a mountain of sulphur [Mammoth Hot Springs]. I have this report from Captain Bridger, who is familiar with every one of these mountains, having passed thirty years of his life near them.

Lt. J. W. Gunnison, an army officer attached to the Stansbury exploring party which Jim Bridger guided to the Great Salt Lake in 1849, was sufficiently impressed with Jim's geographical knowledge to comment as follows:

He has been very active, and traversed the region from the headwaters of the Missouri to the Del Norte—and along the Gila to the Gulf, and thence throughout Oregon and the interior of California. His graphic sketches are delightful romances. With a buffalo-skin and a piece of charcoal, he will map out any portion of this immense region, and delineate mountains, streams, and the circular valleys called 'holes', with wonderful accuracy; at least we may so speak of that portion we traversed after his descriptions were given. He gives a picture, most romantic and enticing of the head-waters of the Yellow Stone. A lake sixty miles long, cold and pellucid, lies embosomed amid high precipitous mountains. On the west side is a sloping plain several miles wide, with clumps of trees and groves of pine. The ground resounds to the tread of horses. Geysers spout up seventy feet high, with a terrific hissing noise, at regular intervals. Waterfalls are sparkling, leaping, and thundering down the precipices, and collect in the pool below. The river issues from this lake, and for fifteen miles roars through the perpendicular canyon at the outlet. In this section are the Great Springs, so hot that meat is readily cooked in them, and as they descend on the successive terraces, afford at length delightful baths. On the other side is an acid spring, which gushes out in a river torrent; and below is a cave which supplies "vermillion" for the savages in abundance. Bear, elk, deer, wolf, and fox are among the game, and the feathered tribe yields its share for variety, on the sportsman's table of rock or turf. [77]

The figure Gunnison gave for the length of Yellowstone Lake—60 miles—is the same as that shown on DeSmet's manuscript map. Such consistency, and an innate conservatism, were both characteristics of Bridger's recital when passing on serious geographical information.

Jim Bridger was not the only purveyor of information about the Yellowstone region; other ex-trappers who had located along the emigrant road to trade in horses and oxen, provide supplies and do a little guiding, occasionally told wayfarers of the things they had seen on the headwaters of the Yellowstone River. Joaquin Miller was one of those who heard such tales, of which he says:

. . . when with my father on Bear River between Fort Hall and Salt Lake at a place then known as Steamboat Spring, in 1852, a trapper told us that there were thousands of such springs at the head of the Yellowstone, and that the Indians there used stone knives and axes. We had Lewis and Clarke's as well as some of Fremont's journals, and not finding any of these hot springs and geysers mentioned in their pages, we paid little attention to the old man's tale. [78]

Indians sometimes served as informants, as Capt. John Mullan noted:

As early as the winter of 1853, which I spent in these mountains, my attention was called to the mild open region lying between the Deer Lodge Valley and Fort Laramie . . . . Upon investigating the peculiarities of the country, I learned from the Indians, and afterwards confirmed by my own explorations, the fact of the existence of an infinite number of hot springs at the headwaters of the Missouri, Columbia, and Yellowstone rivers, and that hot geysers, similar to those of California, existed at the head of the Yellowstone; that this line of hot springs was traced to the Big Horn, where a coal-oil spring, similar in all respects to those worked in west Pennsylvania and Ohio, exists. [79]

Yet another army officer who gained some knowledge of the Yellowstone region during this period was Capt. William F. Raynolds of the Corps of Topographical Engineers. The expedition he commanded was charged particularly with determining the most direct and feasible route "From the Yellowstone to the South Pass, and to ascertaining the practicability of a route from the sources of Wind river to those of the Missouri." Thus, his exploration of the headwaters of the Yellowstone River had to be subordinated to those objectives. The first was accomplished by Lt. H. E. Maynadier, who took a party from Wind River northward through the Wyoming Basin to the Yellowstone River and thence to the Three Forks of the Missouri, where he was to meet Captain Raynolds, who hoped to cross directly to the upper Yellowstone and follow that stream down to the meeting place. However, this second part of the plan went awry.

Of his desire to pass from the head of Wind River to the head of the Yellowstone, Raynolds admits:

Bridger had said at the outset that this would be impossible . . . [and] remarked triumphantly and forcibly to me upon reaching this spot, "I told you you could not go through. A bird can't fly over that without taking a supply of grub along." I had no reply to offer, and mentally conceded the accuracy of the information of "the old man of the mountains." [80]

Being thus prevented from reaching the Yellowstone region from the Atlantic slope, Raynolds crossed the Continental Divide by way of Union Pass and made another attempt from the Gros Ventre fork of Snake River. But late-lying snow banks baffled him there, and, having used as much time as his close schedule allowed, he decided to pass around the western flank of the Yellowstone Plateau and down the Madison River to the rendezvous at the Three Forks. Some idea of the disappointment that decision brought is evident in Captain Raynolds' statement:

We were compelled to content ourselves with listening to marvellous tales of burning plains, immense lakes, and boiling springs, without being able to verify these wonders. I know of but two white men who claim to have visited this part of the Yellowstone valley—James Bridger and Robert Meldrum. The narratives of both of these men are very remarkable, and Bridger in one of his recitals, describes an immense boiling spring that is the very counterpart of the geysers of Iceland. . . . I have little doubt that he spoke of what he had actually seen. The burning plains described by these men may be volcanic, or more probably beds of lignite, similar to those on Powder river, which are known to be in a state of ignition. Bridger also insisted that immediately west [north] of the point at which we made our final effort to penetrate this singular valley, there is a stream of considerable size, which divides and flows down either side of the water-shed, thus discharging its waters into both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Having seen this phenomenon on a small scale in the highlands of Maine, where a rivulet discharges a portion of its waters into the Atlantic and the remainder into the St. Lawrence, I am prepared to concede that Bridger's "Two Ocean river may be a verity. [81]

To that the captain added that he could not doubt "that at no very distant day the mysteries of this region will be fully revealed, and though small in extent, I regard the valley of the upper Yellowstone as the most interesting unexplored district in our widely expanded country."

The map which accompanied Captain Raynolds' belated report (publication was delayed by the Civil War), though generally less informative than either the Hood or the Bridger-DeSmet maps, does add something to the body of knowledge concerning the Yellowstone region. [82] Northwest of the outlet of a spindle-shaped "Yellowstone Lake"—but south of "Falls of the Yellowstone"—is "Elephants Back Mt." Below the falls, and in the proper location to represent Mammoth Hot Springs, is "Sulpher Mt.," while a "Mt. Gallatin" makes its appearance in the position of present Mount Holmes. Raynolds' map also confirms the location of the "Burnt Hole" of the trappers, showing it to lie between Henry's Lake and Mount Holmes (see map 6).

Of that valley, which would later be confused with the geyser basins on Firehole River, Raynolds says:

After crossing Lake fork [below Henrys Lake], Mr. Hutton, Dr. Hayden, and two attendants turned to the east and visited the pass [Targhee] over the mountains, leading into the Burnt Hole valley [Madison Basin]. They found the summit distant only about five miles from our route, and report the pass as in all respects equal to that through which the train had gone [Raynolds Pass]. From it they could see a second pass upon the other side of the valley, which Bridger states to lead to the Gallatin. He also says that between that point and the Yellowstone there are no mountains to be crossed." [83]

Punchbowl Spring, 1902, by William

Henry Jackson.

(Yellowstone National Park)

Gold strikes on the Clearwater, Salmon, Owyhee, and Boise tributaries of Snake River in the opening years of the 1860's led to establishment of the "Idaho mines," from which prospectors moved eastward, across the Continental Divide, to yet another goldfield. But the placers on Grasshopper Creek, where the town of Bannack sprang up in 1862-63, were disappointing to many and they continued to search for gold east of the Rocky Mountains.

Among the latter were 40 prospectors who banded together under "Colonel" Walter Washington deLacy to explore the headwaters of Snake River in the late summer of 1863. By the time they reached the forks of Snake River and were within the south boundary of the present park, the party had splintered several times, and another division near that place resulted in Charles Ream leading a group up Lewis River to Shoshone Lake, over the divide to the Firehole River and down that stream to the Madison, while deLacy conducted his party across the Pitchstone Plateau to Shoshone Lake, then over the divide by way of DeLacy and White Creeks into the Lower Geyser Basin, from which they, too, continued down Firehole River to the Madison and out of the Yellowstone region proper.

Two years later deLacy, who was a well-trained civil engineer, prepared a map of the Territory of Montana which was used by the First Legislative Assembly for laying out the original counties, [84] and the discoveries made by the 1863 parties were thus made public knowledge. The principal contribution of deLacy's map to the geographical knowledge of the Yellowstone region was its essentially correct delineation of the Lewis River headwaters of the Snake. He was the first to show that branch as heading in what is now Shoshone Lake (he did not name the Lake, [85] though he noted its hot spring basin; see map 7). Thus, he avoided the mistake made by DeSmet in 1851, and later by the Hayden Survey, in assigning Lewis and Shoshone Lakes to the Madison drainage. This map also indicated the geyser basins of the Firehole River in its label, "Hot Spring Valley."

It is sometimes claimed that deLacy forfeited his right to consideration as the discoverer of Yellowstone's thermal features because he did not adequately publish his findings, a line of reasoning which assumes he was too much concerned with prospecting to appreciate the wonderful region he passed through. However, an excerpt from one of his letters which found its way into print in 1869 shows that he understood both the extent and the nature of the thermal areas he saw, for he wrote: "At the head of the South Snake, and also on the south fork of the Madison, there are hundreds of hot springs, many of which are 'Geysers'." [86]

The extent of deLacy's familiarity with the southwestern quarter of what is now Yellowstone National Park is evident in the account he later published from notes made in 1863 (cited in Note 85):