|

Yellowstone National Park: Its Exploration and Establishment Part II: Definitive Knowledge |

|

|

|

A systematic knowledge of the Yellowstone region resulted from the explorations of the Folson party (1869), the Washburn party (1870), and the Hayden party (1871). Their combined efforts provided a basis for the reservation of the Yellostone wonders in the public interest.

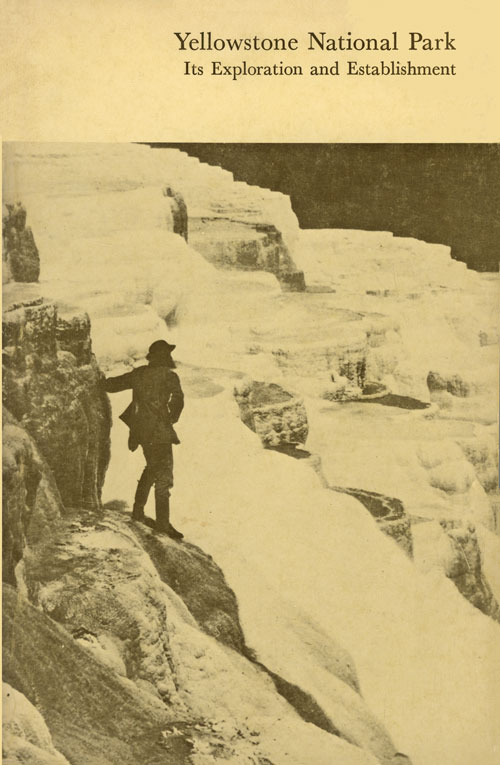

Mammoth Hot Springs, 1871, by

William Henry Jackson.

(U.S. Geological Survey)

The exploring parties of 1869, 1870, and 1871, whose cumulative accomplishment was a definitive knowledge of the Yellowstone region, were a direct outgrowth of an earlier interest in the area's wonders. Thus, it is necessary to go back a few years for the genesis of those efforts through which the true nature of "wonderland" became generally recognized.

An incidental outcome of the visit of Father Francis Xavier Kuppens to the Yellowstone region in the company of Blackfoot Indians in the spring of 1865 (see Part I) was his relation of that experience to a party of gentlemen who were stormbound for several days at the old St. Peter's Mission near the mouth of Sun River the following October. These men, among whom were acting Territorial Governor Thomas Francis Meagher, Territorial Judges H. L. Hosmer and Lyman E. Munson, two deputy U.S. Marshals—X. Beidler and Neil Homie—and a young lawyer named Cornelius Hedges, were traveling from Helena to Fort Benton to assist in negotiating a treaty with the Piegan Indians when overwhelmed by a sudden, savage blizzard and forced to seek shelter at the mission.

Hedges says: ". . . We were received with a warm welcome and all our wants were abundantly supplied and we were in condition to appreciate our royal entertainment." [1] Concerning the story-telling with which the time was passed during that stay at the mission, Father Kuppens adds: [2]

On that occasion I spoke to him [Meagher] about the wonders of the Yellowstone. His interest was greatly aroused by my recital and perhaps even more so, by that of a certain Mr. Viell [3]—an old Canadian married to a Blackfoot squaw—who during a lull in the storm had come over to see the distinguished visitors. When he was questioned about the Yellowstone he described everything in a most graphic manner. None of the visitors had ever heard of the wonderful place. Gen. Meagher said if things were as described the government ought to reserve the territory for a national park. All the visitors agreed that efforts should be made to explore the region and that a report of it should be sent to the government.

As previously mentioned, the Indian unrest occasioned by the opening of the Bozeman Trail route prevented an implementation of Meagher's suggestion during 1866, and, when conditions were at last satisfactory for an expedition into the Yellowstone region—through establishment of Fort Elizabeth Meagher and Camp Ida Thoroughman by the Montana volunteers early in 1867—the tragic death of Acting Governor Meagher cooled the enthusiasm of most of the gentlemen who had made plans to explore the headwaters of the Yellowstone River. While a party did go as far as Mammoth Hot Springs (the Curtis-Dunlevy expedition mentioned in Part I), their visit was essentially a prospecting junket.

No effort was made during 1868 to organize a general exploration of the Yellowstone region, at least so far as the public records show; but there was individual interest in such a project. Of this, Charles W. Cook says:

The first attempt made by me to make an exploration trip to the headwaters of the Yellowstone and Madison rivers was in 1868. At that time I had charge of the "Boulder Ditch Company" at Diamond City. A Mr. Clark, who as I remember, was connected with some mining operations was at Diamond City, and since there was no hotel, was staying at the "Ditch Office." I found he had traveled extensively and had, at times contributed articles to magazines. I told him about the region at the headwaters of the Yellowstone and Madison rivers, which had not been explored, and he became very much interested. We went to Helena to see H. H. McGuire, who published a paper called the Pick and Plow at Bozeman, Montana, but who was at that time visiting Helena. Mr. McGuire advised us that since it was getting late, being then about the middle of September, it was not best to attempt the trip that year. [4]

The following summer, 1869, there was a renewed interest in implementing Meagher's suggestion that the Yellowstone region should be explored. This was publicized in the Helena Herald, in an item announcing:

A letter from Fort Ellis, dated the 19th, says that an expedition is organizing, composed of soldiers and citizens, and will start for the upper waters of the Yellowstone the latter part of August, and will hunt and explore a month or so. Among the places of note which they will visit, are the Falls, Coulter's Hell and Lake, and the Mysterious Mounds. The expedition is regarded as a very important one, and the result of their explorations will be looked forward to with unusual interest. [5]

That notice is undoubtedly the "rumor" which Cook notes as inducing himself and his friend, David E. Folsom, to hold themselves "in readiness to make the trip," to which he adds:

. . . but sometime in the month of August, not having heard from the party, I made a trip to Helena to find out if anyone intended going, and was unable to find anyone who had any intention of making the trip that year. After I returned to Diamond City, David E. Folsom and William Peterson volunteered to make the trip with me. [6]

The manner in which that decision—certainly no trivial one—was arrived at is indicated in the reminiscences of William Peterson:

Myself and two friends—Charley Cook and D. E. Folsom who worked for the same company at Diamond that I did—after having made a trip to Helena to join the big party and finding out that they were not going to go, decided to go ourselves. It happened this way: When we got back from Helena, Cook says, "If I could get one man to go with me, I'd go anyway." I spoke up and said, "Well, Charley, I guess I can go as far as you can," and Folsom says, "Well, I can go as far as both of ye's," and the next thing it was, "Shall we go?" and then, "When shall we start?" We decided to go and started next day . . . . [7]

Hayden Survey camp, Yellowstone Lake, 1871, by William Henry

Jackson.

(U.S. Geological Survey)

Fifty-three years later Cook recalled that start, and the attitude with which friends viewed their venture, quoting thus from his diary:

The long-talked-of expedition to the Yellowstone is off at last but shorn of the prestige attached to the names of a score of the brightest luminaries in the social firmament of Montana, as it was first announced. It has assumed proportions of utter insignificance, and of no importance to anybody in the world except the three actors themselves. Our leave-taking from friends who had assembled to see us start this morning was impressive, in the highest degree and rather cheering withal. "Good-bye, boys, look out for your hair." "If you get into a scrap, remember I warned you." "If you get back at all you will come on foot." "It is the next thing to suicide," etc. etc., were the parting salutations that greeted our ears as we put spurs to our horses and left home and friends behind. [8]

Following their return from the Yellowstone region these explorers were reluctant to prepare an account of what they had seen, for, as Folsom later commented, "I doubted if any magazine editor would look upon a truthful description in any other light than the production of the too-vivid imagination of a typical Rocky Mountain liar." [9] However, they soon received an encouragement which was irresistible. According to Cook, it happened this way:

Soon after my return from the trip of 1869, I received a letter from Mr. Clark, a friend whom I had met the previous year, stating that he had read that an expedition to the source of the Yellowstone and Madison rivers had been contemplated, and, supposing of course that I was with it, wanted to know what we had discovered. I at once answered this letter, giving him some idea of our trip and discoveries. He at once replied and asked for a writeup of all details. I then took the matter up with Mr. Folsom and, as we had not much to do that winter at the "Ditch Company," we prepared an amplified diary by working over both the diaries made on the trip, and combining them into one. . . . Mr. Folsom then added to this diary a preliminary statement, and I forwarded the same to Mr. Clark. He wrote back at once asking my permission to have it published to which request we gave our consent. Later I received a letter from Mr. Clark stating that he had made an effort to have our amplified diary published in the New York Tribune, and also in Scribner's or Harper's magazines, but both refused to consider it for the reason that "they had a reputation that they could not risk with such unreliable material." Finally, he secured its publication in the Western Monthly Magazine, published at Chicago, Illinois, and received, as a compensation, the sum of $18.00. The condition in which this amplified diary appeared in the June number of the Western Monthly Magazine was neither the fault of Mr. Folsom nor myself, as the editor cut out portions of the diary which destroyed its continuity, so far as giving a reliable description of our trip and the regions explored.

In the original article, I alone, was credited with writing the article, but later, when a reprint was made of it by N. P. Langford, he credited it to D. E. Folsom, neither of which are correct. We did not sign the diary sent to Mr. Clark, and, as he did not know Mr. Folsom but had carried on the correspondence with me, he had it credited to me; but the actual facts are as above outlined. [10]

David E. Folsom, Charles W. Cook, and William Peterson left Diamond City, Mont., on September 6, 1869, traveling with saddle and pack animals to the Gallatin Valley. At the town of Bozeman, where they obtained provisions, an attempt was made to recruit some of the townsmen into their enterprise, but without success; however, they did receive some valuable information from George Phelps, one of the prospectors who had returned through the Yellowstone region following the breakup of James Stuart's expedition down the Yellowstone River and into the Wyoming Basin in 1864. From Bozeman the three explorers took the miner's route, by way of Meadow and Trail Creeks, to the Yellowstone River nearly opposite Emigrant Gulch. The account is continued from that point mainly with excerpts from the Cook-Folsom article as it appeared in 1870. [11]

We pushed on up the valley, following the general course of the river as well as we could, but frequently making short detours through the foot-hills, to avoid the deep ravines and places where the hills terminated abruptly at the water's edge. On the eighth day out, we encountered a band of Indians—who, however, proved to be Tonkeys, or Sheepeaters, and friendly; the discovery of their character relieved our minds of apprehension, and we conversed with them as well as their limited knowledge of English and ours of pantomine would permit. [12] For several hours after leaving them, we travelled over a high rolling table-land, diversified by sparkling lakes, picturesque rocks, and beautiful groves of timber. Two or three miles to our left, we could see the deep gorge which the river, flowing westward, had cut through the mountains. [13] The river soon after resumed its northern course; and from this point to the falls, a distance of twenty-five or thirty miles, it is believed to flow through one continuous cañon, through which no one has ever been able to pass. [14]

At this point we left the main river, intending to follow up the east branch for one day, then to turn in a southwest course and endeavor to strike the river again near the falls. After going a short distance, we encountered a cañon about three miles in length, and while passing around it we caught a glimpse of scenery so grand and striking that we decided to stop for a day or two and give it a more extended examination. [15] We picked our way to a timbered point about mid-way of the cañon, and found ourselves upon the verge of an overhanging cliff at least seven hundred feet in height. The opposite bluff was about on a level with the place where we were standing; and it maintained this height for a mile up the river, but gradually sloped away toward the foot of the cañon. The upper half presented an unbroken face, with here and there a re-entering angle, but everywhere maintained its perpendicularity; the lower half was composed of the debris that had fallen from the wall. But the most singular feature was the formation of the perpendicular wall. At the top, there was a stratum of basalt, from thirty to forty feet thick, standing in hexagonal columns;. beneath that, a bed of conglomerate eighty feet thick, composed of washed gravel and boulders; then another stratum of columnar basalt of about half the thickness of the first; and lastly what appeared to be a bed of coarse sandstone. A short distance above us, rising from the bed of the river, stood a monument or pyramid of conglomerate, circular in form, which we estimated to be forty feet in diameter at the base, and three hundred feet high, diminishing in size in a true taper to its top, which was not more than three feet across. It was so slender that it looked as if one man could topple it over. How it was formed I leave others to conjecture. [16] We could see the river for nearly the whole distance through the cañon dashing over some miniature cataract, now fretting against huge boulders that seemed to have been hurled by some giant hand to stay its progress, and anon circling in quiet eddies beneath the dark shadows of some projecting rock. The water was so transparent that we could see the bottom from where we were standing, and it had that peculiar liquid emerald tinge so characteristic of our mountain streams.

Half a mile down the river, and near the foot of the bluff, was a chalky-looking bank, from which steam and smoke were rising; and on repairing to the spot, we found a vast number of hot sulphur springs. [17] The steam was issuing from every crevice and hole in the rocks; and, being highly impregnated with sulphur, it threw off sulphuretted hydrogen, making a stench that was very unpleasant. All the crevices were lined with beautiful crystals of sulphur, as delicate as frost-work. At some former period, not far distant, there must have been a volcanic eruption here. Much of the scoria and ashes which were then thrown out has been carried off by the river, but enough still remains to form a bar, seventy-five or a hundred feet in depth. Smoke was still issuing from the rocks in one place, from which a considerable amount of lava had been discharged within a few days or weeks at farthest. While we were standing by, several gallons of a black liquid ran down and hardened upon the rocks; we broke some of this off and brought it away, and it proved to be sulphur, pure enough to burn readily when ignited. [18]

Reference to the reconstructed account (1965, pp. 26-29) shows that the editor of the Western Monthly cut out that portion of the original manuscript covering the crossing of Yellowstone River, the journey up Lamar River to the mouth of Calfee Creek, and the ascent of Flint Creek to a storm-bound encampment below the rim of Mirror Plateau. The magazine account resumes at that point:

September 1 8th—the twelfth day out—we found that ice had formed one-fourth of an inch thick during the night, and six inches of snow had fallen. The situation began to look a little disagreeable; but the next day was bright and clear, with promise of warm weather again in a few days. Resuming our journey, we soon saw the serrated peaks of the Big Horn Range glistening like burnished silver in the sunlight, and, over-towering them in the dim distance, the Wind River Mountains seemed to blend with the few fleecy clouds that skirted their tops; [19] while in the opposite direction, in contrast to the barren snow-capped peaks behind us, as far as the eye could reach, mountain and valley were covered with timber, whose dark green foliage deepened in hue as it receded, till it terminated at the horizon in a boundless black forest. Taking our bearings as well as we could, we shaped our course in the direction in which we supposed the falls to be.

The next day (September 20th), we came to a gentle declivity at the head of a shallow ravine, from which steam rose in a hundred columns and united in a cloud so dense as to obscure the sun. In some places it spurted from the rocks in jets not larger than a pipe-stem; in others it curled gracefully up from the surface of boiling pools from five to fifteen feet in diameter. In some springs the water was clear and transparent; others contained so much sulphur that they looked like pots of boiling yellow paint. One of the largest was as black as ink. Near this was a fissure in the rocks, several rods long and two feet across in the widest place at the surface, but enlarging as it descended. We could not see down to any great depth, on account of the steam but the ground echoed beneath our tread with a hollow sound, and we could hear the waters surging below, sending up a dull, resonant roar like the break of the ocean surf into a cave. At these springs but little water was discharged at the surface, it seeming to pass off by some subterranean passage. About half a mile down the ravine, the springs broke out again. Here they were in groups, spreading out over several acres of ground. One of these groups—a collection of mud springs of various colors, situated one above the other on the left slope of the ravine—we christened "The Chemical Works." [20] The mud, as it was discharged from the lower side, gave each spring the form of a basin or pool. At the bottom of the slope was a vat, ten by thirty feet, where all the ingredients from the springs above were united in a greenish-yellow compound of the consistency of white lead. Three miles further on we found more hot springs along the sides of a deep ravine, at the bottom of which flowed a creek twenty feet wide. [21] Near the bank of the creek, through an aperture four inches in diameter, a column of steam rushed with a deafening roar, with such force that it maintained its size for forty feet in the air, then spread out and rolled away in a great cloud toward the heavens. We found here inexhaustible beds of sulphur and saltpetre. Alum was also abundant; a small pond in the vicinity, some three hundred yards long and half as wide, contained as much alum as it could hold in solution, and the mud along the shore was white with the same substance, crystallized by evaporation.

On September 21st, a pleasant ride of eighteen miles over an undulating country brought us to the great cañon, two miles below the falls; [22] but there being no grass convenient, we passed on up the river to a point half a mile above the upper falls, and camped on a narrow flat, close to the river bank. [23] We spent the next day at the falls—a day that was a succession of surprises; and we returned to camp realizing as we had never done before how utterly insignificant are man's mightiest efforts when compared with the fulfillment of Omnipotent will. Language is entirely inadequate to convey a just conception of the awful grandeur and sublimity of this masterpiece of nature's handiwork; and in my brief description I shall confine myself to bare facts. Above our camp the river is about one hundred and fifty yards wide, and glides smoothly along between gently-sloping banks; but just below, the hills crowd in on either side, forcing the water into a narrow channel, through which it hurries with increasing speed, until, rushing through a chute sixty feet wide, it falls in an unbroken sheet over a precipice one hundred and fifteen feet in height. [24] It widens out again, flows with steady course for half a mile between steep timbered bluffs four hundred feet high, and again narrowing in till it is not more than seventy-five feet wide, it makes the final fearful leap of three hundred and fifty feet. [25] The ragged edges of the precipice tear the water into a thousand streams—all united together, and yet apparently separate,—changing it to the appearance of molten silver; the outer ones decrease in size as they increase in velocity, curl outward, and break into mist long before they reach the bottom. This cloud of mist conceals the river for two hundred yards, but it dashes out from beneath the rainbow-arch that spans the chasm, and thence, rushing over a succession of rapids and cascades, it vanishes at last, where a sudden turn of the river seems to bring the two walls of the cañon together. Below the falls, the hills gradually increase in height for two miles, where they assume the proportions of mountains. Here the cañon is at least fifteen hundred feet deep, with an average width of twice that distance at the top. For one-third of the distance downwards the sides are perpendicular,—from thence running down to the river in steep ridges crowned by rocks of the most grotesque form and color; and it required no stretch of the imagination to picture fortresses, castles, watch-towers, and other ancient structures, of every conceivable shape. In several places near the bottom, steam issued from the rocks; and, judging from the indications, there were at some former period hot springs or steam-jets of immense size all along the wall.

The next day we resumed our journey, traversing the northern slope of a high plateau between the Yellowstone and Snake Rivers. [26] Unlike the dashing mountain—stream we had thus far followed, the Yellowstone was in this part of its course wide and deep, flowing with a gentle current along the foot of low hills, or meandering in graceful curves through broad and grassy meadows. Some twelve miles from the falls we came to a collection of hot springs that deserve more than a passing notice. These, like the most we saw, were situated upon a hillside; and as we approached them we could see the steam rising in puffs at regular intervals of fifteen or twenty seconds, accompanied by dull explosions which could be heard half a mile away, sounding like the discharge of a blast underground. These explosions came from a large cave that ran back under the hill, [27] from which mud had been discharged in such quantities as to form a heavy embankment twenty feet higher than the floor of the cave, which prevented the mud from flowing off; but the escaping steam had kept a hole, some twenty feet in diameter, open up through the mud in front of the entrance to the cave. The cave seemed nearly filled with mud, and the steam rushed out with such volume and force as to lift the whole mass up against the roof and dash it out into the open space in front; and then, as the cloud of steam lifted, we could see the mud settling back in turbid waves into the cavern again. Three hundred yards from the mud-cave was another that discharged pure water; the entrance to it was in the form of a perfect arch, seven feet in height and five in width. [28] A short distance below these caves were several large sulphur springs, the most remarkable of which was a shallow pool seventy-five feet in diameter, in which clear water on one side and yellow mud on the other were gently boiling without mignling.

September 24th we arrived at Yellowstone Lake, [29] about twenty miles from the falls. The main body of this beautiful sheet of water is ten miles wide from east to west, and sixteen miles long from north to south; but at the south end it puts out two arms, one to the southeast and the other to the southwest, making the entire length of the lake about thirty miles. Its shores—whether gently sloping mountains, bold promontories, low necks, or level prairies—are everywhere covered with timber. The lake has three small islands, which are also heavily timbered. The outlet is at the northwest extremity. The lake abounds with trout, and the shallow water in its coves affords feeding ground for thousands of wild ducks, geese, pelicans, and swans.

We ascended to the head of the lake, [30] and remained in its vicinity for several days, resting ourselves and our horses, and viewing the many objects of interest and wonder. Among these were springs differing from any we had previously seen. They were situated along the shore for a distance of two miles, extending back from it about five hundred yards and into the lake perhaps as many feet. The ground in many places gradually sloped down to the water's edge, while in others the white chalky cliffs rose fifteen feet high—the waves having worn the rock away at the base, leaving the upper portion projecting over in some places twenty feet. There were several hundred springs here, varying in size from miniature fountains to pools or wells seventy-five feet in diameter and of great depth; the water had a pale violet tinge, and was very clear, enabling us to discern small objects fifty or sixty feet below the surface. In some of these, vast openings led off at the side; and as the slanting rays of the sun lit up these deep caverns, we could see the rocks hanging from their roofs, their water-worn sides and rocky floors, almost as plainly as if we had been traversing their silent chambers. These springs were intermittent, flowing or boiling at irregular intervals. The greater portion of them were perfectly quiet while we were there, although nearly all gave unmistakable evidence of frequent activity. Some of them would quietly settle for ten feet, while another would as quietly rise until it overflowed its banks, and send a torrent of hot water sweeping down to the lake. At the same time, one near at hand would send up a sparkling jet of water ten or twelve feet high, which would fall back into its basin, and then perhaps instantly stop boiling and quietly settle into the earth, or suddenly rise and discharge its waters in every direction over the rim; while another, as if wishing to attract our wondering gaze, would throw up a cone six feet in diameter and eight feet high, with a loud roar. These changes, each one of which would possess some new feature, were constantly going on; sometimes they would occur within the space of a few minutes, and again hours would elapse before any change could be noted. At the water's edge, along the lake shore, there were several mounds of solid stone, on the top of each of which was a small basin with a perforated bottom; these also overflowed at times, and the hot water trickled down on every side. Thus, by the slow process of precipitation, through the countless lapse of ages, these stone monuments have been formed. A small cluster of mud springs near by claimed our attention. [31] They were like hollow truncated cones and oblong mounds, three or four feet in height. These were filled with mud, resembling thick paint of the finest quality—differing in color, from pure white to the various shades of yellow, pink, red, and violet. Some of these boiling pots were less than a foot in diameter. The mud in them would slowly rise and fall as the bubbles of escaping steam, following one after the other, would burst upon the surface. During the afternoon, they threw mud to the height of fifteen feet for a few minutes, and then settled back to their former quietude.

As we were about departing on our homeward trip, we ascended the summit of a neighboring hill, and took a final look at Yellowstone Lake. Nestled among the forest-crowned hills which bounded our vision, lay this inland sea, its crystal waves dancing and sparkling in the sunlight, as if laughing with joy for their wild freedom. It is a scene of transcendent beauty, which has been viewed by but few white men; and we felt glad to have looked upon it before its primeval solitude should be broken by the crowds of pleasure-seekers which at no distant day will throng its shores. [32]

September 29th, we took up our march for home. Our plan was to cross the range in a northwesterly direction, find the Madison River, and follow it down to civilization. Twelve miles brought us to a small triangular-shaped lake, about eight miles long, deeply set among the hills. [33] We kept on in a northwesterly direction, as near as the rugged nature of the country would permit; and on the third day (October 1st) came to a small irregularly shaped valley, some six miles across in the widest place, from every part of which great clouds of steam arose. From descriptions which we had had of this valley, from persons who had previously visited it, we recognized it as the place known as "Burnt Hole," or "Death Valley." The Madison River flows through it, and from the general contour of the country we knew that it headed in the lake which we passed two days ago, [34] only twelve miles from the Yellowstone. We descended into the valley, and found that the springs had the same general characteristics as those I have already described, although some of them were much larger and discharged a vast amount of water. One of them, at a little distance, attracted our attention by the immense amount of steam it threw off; and upon approaching it we found it to be an intermittent geyser in active operation. [35] The hole through which the water was discharged was ten feet in diameter, and was situated in the centre of a large circular shallow basin, into which the water fell. There was a stiff breeze blowing at the time, and by going to the windward side and carefully picking our way over convenient stones, we were enabled to reach the edge of the hole. At that moment the escaping steam was causing the water to boil up in a fountain five or six feet high. It stopped in an instant, and commenced settling down—twenty, thirty, forty feet—until we concluded that the bottom had fallen out; but the next instant, without any warning, it came rushing up and shot into the air at least eighty feet, causing us to stampede for higher ground. It continued to spout at intervals of a few minutes, for some time; but finally subsided, and was quiet during the remainder of the time we stayed in the vicinity. We followed up the Madison five miles, and there found the most gigantic hot springs we had seen. They were situated along the river bank, and discharged so much hot water that the river was blood-warm a quarter of a mile below. One of the springs was two hundred and fifty feet in diameter, and had every indication of spouting powerfully at times. [36] The waters from the hot springs in this valley, if united, would form a large stream; and they increase the size of the river nearly one-half. Although we experienced no bad effects from passing through the "Valley of Death," yet we were not disposed to dispute the propriety of giving it that name. [37] It seemed to be shunned by all animated nature. There were no fish in the river, no birds in the trees, no animals—not even a track—anywhere to be seen; although in one spring we saw the entire skeleton of a buffalo that had probably fallen in accidentally and been boiled down to soup.

Leaving this remarkable valley, we followed the course of the Madison—sometimes through level valleys, and sometimes through deep cuts in mountain ranges,—and on the fourth of October emerged from a cañ, ten miles long and with high and precipitous mountain sides, to find the broad valley of the Lower Madison spread out before us. Here we could recognize familiar landmarks in some of the mountain peaks around Virginia City. From this point we completed our journey by easy stages, and arrived at home on the evening of the eleventh. We had been absent thirty-six days—a much longer time than our friends had anticipated;—and we found that they were seriously contemplating organizing a party to go in search of us.

Nathaniel P. Langford deprecated the importance of the foregoing Cook-Folsom article, stating:

The office of the Western Monthly, of Chicago, was destroyed by fire soon after the publication of Mr. Folsom's account of his discoveries, and the only copy of that magazine which he possessed, and which he presented to the Historical Society of Montana, met a like fate in the great Helena fire. The copy which I possess is perhaps the only one to be found. [38]

However, the office of the Western Monthly, or the Lakeside Monthly as it was called after 1870, was destroyed in the Chicago fire of October 3-9, 1871, so that subscribers had the July 1870 issue for well over a year prior to that holocaust, and it is not as rare as Langford supposed.

There is no way to judge the impact of the Cook-Folsom article, but there is evidence that the information brought back by the Folsom party of 1869 was influential in launching the Washburn party of 1870. N. P. Langford has testified to the inspirational value of this exploration in the following words:

On his return to Helena he [Folsom] related to a few of his intimate friends many of the incidents of his journey, and Mr. Samuel T. Hauser and I invited him to meet a number of the citizens of Helena at the director's room of the First National Bank in Helena; but on assembling there were so many present who were unknown to Mr. Folsom that he was unwilling to risk his reputation for veracity, by a full recital, in the presence of strangers, of the wonders he had seen. He said that he did not wish to be regarded as a liar by those who were unacquainted with his reputation. But the accounts which he gave to Hauser, Gillette and myself renewed in us our determination to visit that region during the following year. [39]

But encouragement was not the whole of Folsom's assistance to the Washburn party; he also provided geographical information. Soon after his return from the Yellowstone wilderness, Folsom took employment in the Helena office of the new Surveyor-General of Montana Territory, Henry D. Washburn. There,, he worked with that other civil engineer and Yellowstone explorer, Walter W. deLacy, and together they turned out a noteworthy map.

This map, [40] which is endorsed over the signature of Commissioner Joseph S. Wilson of the General Land Office as "accompanying Commissioner's s Annual Report for 1869," was dated at Helena, Mont., November 1, 1869—a mere 21 days after the return of the Folsom party to Diamond City. On it, the Yellowstone region was revealed in greater detail than ever before, and its portrayal was, at last, reasonably accurate (see map 9.). The "Route of Messrs Cook & Folsom 1869" was shown, and along that track, such prominent features as "Gardner's River," with its "Hot Spgs" (Mammoth Hot Springs); the "East Fork," now Lamar River, with "Burning Spring" (Calcite Springs) near its mouth; "Alum Creek" and some thermal features on Broad Creek; the falls of the Yellowstone (the upper noted as "115 ft." and the lower as "350 ft."); "Hot Spgs." noted at the Crater Hills and on Trout Creek, and a "Mud Spring" nearer the outlet of Yellowstone Lake (the Mud Volcano area). The lake was shown as a two-armed body of water, with a "Main Fork" (Upper Yellowstone River) discharging into the large, southern arm, and "Hot Spgs" on the west shore of the bulbous western arm. Interestingly, three islands were clearly shown in the lake (Stevenson, Dot, and Frank), and "Hot Springs" were noted on a point on the northeastern shore (Steamboat Point), and near Pelican Creek.

A new feature added by these explorers was a triangular "Madison Lake," placed west of Yellowstone Lake in accordance with their experience of coming down on the east shore of a large lake after traveling westward from the hot springs at West Thumb. This lake was not recognized for what it was—"Delacy's" or Shoshone Lake—because of an accumulation of mapping errors. Most Yellowstone features are positioned 15 or more miles too far to the west on this General Land Office map, and 11 to 20 miles too far to the north, when compared with present-day maps. However, "DeLacy's Lake," although similarly misplaced in its longitude, is shown only 2 miles north of the correct latitude for its outlet. [41] Thus, when the Folsom party found a large lake nearly 20 miles north of the map position of deLacy's, they failed to relate the two and added a lake which they presumed to be the head of the Madison River, hence its name.

On the Madison River, "Hot Springs" were shown at the head of its southern branch (Firehole River), and both "Hot Springs" and "Geysers" where the eastern branch—presumed to drain "Madison Lake"—joined the former stream. Except for the inconsistencies caused by the introduction of the fictitious "Madison Lake," and omission of Heart Lake and the headwaters of Snake River, the Cook-Folsom information had produced a reasonably good map. How much better it was than the map it superseded [42] is evident at a glance (see map 8).

The information brought back by the Folsom party soon appeared in another form of greater importance than the General Land Office map because of its wider distribution and the fact that a copy was carried through the Yellowstone region by the Washburn party of 1870. A comparison (see map 10), shows that this map had profited from the same improvements apparent on the 1869 General Land Office map, and the usefulness of this 1870 edition of the deLacy map to the Yellowstone explorers of that year is mentioned by Oscar O. Mueller, who says:

Naturally after their return from the exploration trip, they [Cook and Folsom] gave the Surveyor General's Office every possible information they could regarding the region explored and what they had found. W. W. deLacy was employed by the Territory to prepare maps and, therefore, with the assistance of Mr. Folsom, prepared a new map of the Territory of Montana, showing also the north half of the Wyoming Territory. These maps were printed . . . [and] General Washburn took with him, on his exploration trip to the Yellowstone region in 1870, one of these maps and also a copy of the diary of Mr. Cook and Folsom. It can be readily seen, from the inspection of the map covering the Yellowstone region, how valuable an assistance it was to the 1870 expedition. Washburn and Langford were advised to seek a short cut from Tower Falls to the Yellowstone Canyon and Falls. It was this that made General Washburn leave the party at Tower Falls on a Sunday afternoon, and ride up to the top of what is now known as Mount Washburn, from which he could see that the short cut was feasible, and thus they deviated at that point from the route followed by Cook and Folsom in 1869. [44]

While yet employed in the surveyor-general's office—Langford says it was "on the eve of the departure of our expedition from Helena" [45]—Folsom suggested to General Washburn that at least a part of the Yellow stone region should be made into a park. [46]

The contributions of the Folsom party of 1869 to the definitive exploration of the Yellowstone region are these: a descriptive magazine article, a greatly improved map, a suggestion for reservation in the public interest, and the encouragement of the Washburn party of explorers.

Yellowstone Lake, by William

Henry Jackson.

(National Archives)

The motivation that sent the Washburn party into the Yellowstone region in 1870 was largely an outgrowth of two unrelated events of the previous year—the effort to activate the Northern Pacific Railway project, and the struggle over the governorship of the Territory of Montana. Thus, it is necessary to consider these peripheral events before continuing with the definitive exploration of the Yellowstone wilderness.

An act of Congress chartering the Northern Pacific Railway was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on July 2, 1864, but the enterprise remained a paper venture (in which the resources provided by the stockholders were consumed without apparent benefit) through 1869. In that year, the board of directors, made desperate by the knowledge, that they would lose both the charter and the munificent land-grant which accompanied it if the prescribed amount of line was not in operation by the end of 1870, turned to the investment house of Jay Cooke & Co., for help. [47]

This marriage of convenience was not consummated at once, for neither group trusted the other. The "old NP faction," headed by J. Gregory Smith—generally addressed as "Governor"—talked of "keeping things in our hands," because "Jay knows nothing of RR Building," [48] and they moved their secretary, the astute and crafty Samuel Wilkeson into an office in New York City, from whence he could advise the Cooke people and divine something of their maneuverings from the city's financial gossip.

The Cooke group, which also included Henry D. Cooke, Pitt Cooke, William G. Moorhead, H. C. Fahnstock, Edward Dodge, John W. Sexton, and George C. Thomas, was not as poorly informed as their distrustful confederates presumed, for they had the excellent counsel of A. B. Nettleton (Cooke's office manager) who, as a general officer in the Civil War, had built and operated many of the railroads which gave the North its logistical superiority in that struggle. These financiers were fearful that the railroaders would waste construction funds in contractual arrangements with cronies, and that the lands available under the railroad's grant—the real security for its bond issues—would be wasted.

The two groups sparred over terms during the remainder of 1869, but finally reached an agreement which gave the banking house representation on the Northern Pacific board and a controlling interest in the railroad's stock in return for an immediate advance of $5 million. [49] That funding allowed construction to begin on the Minnesota shore of Lake Superior, February 15, 1870, on ground thawed with bonfires. [50]

The enterprise thus launched had supporters in and out of the Government, from House Speaker James G. Blaine to Henry Ward Beecher, most of whom had such compelling reasons for their interest as the ownership of Northern Pacific stock or acceptance of gratuities and "fees"; and there were would-bc-friends in the West who sought to ingratiate themselves with the enterprise for various opportunistic reasons. Some of the latter found a measure of acceptance with the Cooke faction, but to the railroaders they were nearly all anathema—a viewpoint which is explained by the following excerpt:

. . . Governor Ashley and a rich man from Toledo, Ohio have put squatters on our pet, our choice, location at Thompson Falls. The choisest and best land on our line of reconnaissance within a year will be gone. [51]

One westerner—a term intended only to designate those men whose sphere of activity was Minnesota and Montana, rather than the financial centers of the East—who nearly made the grade with the old Northern Pacific group was the editor of the Helena Herald. He was introduced to President Smith in these glowing terms penned by Samuel Wilkeson:

Robert E. Fiske—the bearer—is the Republican Editor of Montana—and the Republican brains & heart of that future mighty State.

He loves our Road—Our Road should love & cherish him.

Every syllable of his advice is worth heeding. [52]

But he was not heeded; rather, he was soon considered a "wicked or mean" man, on the advice of one whose contacts were Montana Democrats. [53] The railroaders thus turned their backs on a group which could have been formed into a powerful ally.

The Cooke people were not so disdainful of westerners. They made use of Governor Ashley, even after his true character was all too clear, and they leaned heavily on William R. Marshall, the Governor of Minnesota (1866-70). [54] Quite probably, the latter arrangement included Marshall's brother-in-law, James W. Taylor, [55] that enthusiastic apostle of American economic penetration of the Canadian prairies (which he presumed would eventuate as a "Northern Texas," wrested from British rule by American citizens), but what is important here is the influence of these men—particularly Taylor—on a younger brother-in-law, Nathaniel Pitt Langford. Of this influence, one biographer says:

Langford's story in Montana's early history is well known. That he was an "agent of an agent" there seems little doubt. Indirectly he was an observer and a protagonist for the northern railroad routes. During his time in Montana he seems always to be acting as he would expect Taylor to act and speak if he were there on the scene. His interest in getting Virginia City's gold safely to Washington, and in securing the resources of the area for the Union seem honestly to have been his conscious effort. . . . That N. P. Langford was not James Wicks Taylor is just as obvious, but he did his best. [56]

Taylor, of course, was the source of Langford's political leverage. As a former law partner of Salmon P. Chase (with whom he enjoyed a close ideological rapport), Taylor was able to obtain the position of Collector of Internal Revenue for Montana Territory for his protégé, and he nearly managed the governorship of the territory for him in 1869. [57] Following that defeat Langford gradually became involved in the familial interest—the Northern Pacific Railroad.

Langford, whose diary indicates that he left Montana on October 26, 1869, [58] showed up at the New York office of the Northern Pacific on March 18, 1870. Secretary Wilkeson reported this visit to President Smith in a confidential letter, as follows:

A smart fellow, anciently a bookkeeper—during the war detailed as quartermaster to an expedition from Minnesota overland to Fort Benton and thence through Cadottes, the Deer Lodge & other passes, came in yesterday to get employment. Before he left he asked me if Vibbard & Co. were to have the contract of supplying the Northern Road—and said that he was told by that house the day preceding that they expected to have the contract. Canfield Probably told you of my conversation with Vibbard six months ago on the subject of that contract. I was told then that I was to have an interest in it. [59]

An item which appeared in the Philadelphia Press the day following this visit is so patent a re-statement of James W. Taylor's views that Langford may be suspected of supplying the material to enhance the sale-value of his knowledge of Montana and the northern railroad route. [60] But he was displaying his wares in a poor market, for the railroad could not afford a salary for its secretary at that time.

From April 4 to May 11, Langford accompanied brother-in-law Marshall on a trip to Fort Garry, in British territory. By the middle of the month, Marshall was advocating the construction of a White Cloud-Pembina line to tap the rich Red River Valley (He made several attempts to communicate his enthusiasm for that route to President Smith [61]). As June opened, Langford was in Washington, D.C., in a further attempt to contact Smith. [62]

Though unable to reach the autocrat of the Northern Pacific Railroad, Langford did manage a meeting with Jay Cooke 2 days later. This is noted in Langford's diary as follows:

June 4, 1870, Sat. Met Jay Cooke [illegible] and went to Ogontz [63] with Mr. Cook.

June 5, 1870, Sun. Spent day with Mr. Cook.

What their common interest was remains a matter for speculation, but the directness with which Langford returned to Montana Territory and began organizing the 1870 exploring party hints that the Yellowstone region figured in the conversations. Regardless, Langford had found a place as one of the corps of lecturers who were to expedite the sale of Northern Pacific Railway bonds by popularizing the region through which the line was to be built.

Lower Falls of the

Yellowstone, by William Henry Jackson.

(National

Archives)

From Philadelphia, Langford proceeded to the family home at Utica, N.Y., where he visited briefly before going on to St. Paul, Minn., and a series of pleasant visits with his many relatives in that area. While there, he called upon Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock, who commanded the Military Department of Dakota (of which Montana was then a part), and that officer

. . . showed great interest in the plan of exploration which I outlined to him, and expressed a desire to obtain additional information concerning the Yellowstone country . . . and he assured me that, unless some unforseen exigency prevented, he would, when the time arrived, give a favorable response to our application for a military escort, if one were needed. [64]

Even as Langford was making his plans for a late summer expedition into the Yellowstone region, another interested explorer made an attempt to enter that area. While his venture contributed nothing to the knowledge of Yellowstone's unusual features, it may have influenced the Washburn party in their selection of the Yellowstone River route as the proper approach to the wilderness, and it does expose the vagueness of whatever plan existed locally, prior to Langford's return early in August 1870.

As spring turned to summer, Philetus W. Norris returned to Montana to further his various land schemes along the projected route of the Northern Pacific Railway. Of this visit he says: [65]

At Helena I learned from Gen. Washburn and T. C. Everts that there were rumors of Capt. deLacy, Messrs. Cook and Folsom, and some gold hunters having at various times reached some portions of the Geyser regions, but so far I have failed to find any published or other reliable description of them, or their location or route of reaching them.

Gov. Ashley, Washburn and Everts were talking of a party up the Madison in the following autumn.

Firm in the opinion that the Yellowstone route was the true one, I obtained all possible information here and at Bozeman, and near the latter place found an old used up mountaineer named Dunn, who claimed to have gone with James Bridger and another trapper, who was soon after killed by the Indians in Arizona, via Yellowstone Lake to Green River, in 1865, and, from his statements I made a rough map of their route. [66]

Leaving Everts at Fort Ellis [where he had business with the post sutler], with horse and Winchester rifle, I alone followed the Indian trail through the famous Spring Canon, and left the main pass and trail near the lignite coal bed. I thence crossed the beautiful grassy divide, still full of buffalo wallows, and following a continuous line of rough stone heaps from 2 to 5 feet high, to, and beyond Trail creek an estimated distance of 40 miles from here without seeing a human habitation, to the only one of white men upon the north bank of the Yellowstone.

Norris stopped there for several days with the Bottler brothers—Frederick, Philip, and Henry, [67] enjoying their wild solitude. However,

The main object of my visit being to ascertain the possibility of an exploring party going through the upper cañon and the Lava, or ancient volcanic country beyond, so as to reach the wonders said to be around Yellowstone Lake, several days were spent, with Frederick Bottler as guide, in climbing the Basaltic mountains and dark defiles, the mountain horses of Cayuse characteristics, climbing, like goats or mountain sheep, much of the way. Assured that with the fall of waters a party might in August reach at least the great falls of Yellowstone, we ought to have returned, but believing the Indians were across the next range of mountains upon a buffalo hunt, elated with the wonders found, and hoping to reach greater, and if possible be the first men to reach the Sulphur Mountains and Mud Volcanoes, and possibly the great falls and Yellowstone Lake, we rashly pushed on.

Although the snow-capped cliffs and yawning chasms in the basaltic or ancient lava beds, fringed with snow-crushed, tangled timber and impetuous torrents of mingled hot-spring and melted-snow water, made our progress-mainly on foot, leading our horses—slow, tedious and dangerous, we perservered until near a large river [68] that came dashing down from the Southwestern Madison range. There while crossing a mountain torrent, though the water was not over 20 feet wide and less than knee deep, such was its velocity that Bottler, who first entered, was carried from his feet and swept away much faster than I could follow, and though in great danger of being dashed amongst the rocks, he fortunately caught an overhanging cottonwood and by our united efforts was saved, but his valuable needle-gun, hat, ammunition-belt and equipments went dashing down toward the Yellowstone and were lost.

With my only companion sadly bruised by the rocks, benumbed, the remnants of his dressed elk-skin garments saturated by the snow-water, without gun or pistol, in a snow-bound mountain defile in an Indian country, even a June night was far from pleasant for us.

A morning view with an eight-mile field-glass, though disclosing distant clouds of smoke or spray [Mammoth Hot Springs], yet convinced us both of the utter folly of further effort until melting snows reduced the velocity and number of these mountain torrents, and we should be prepared with more than one gun for procuring food and defence from animals and Indians. As Bottler was unable to climb the mountains, [69] we returned through the unknown second cañon, camping in it while I explored the route.

In a note added at the time he edited these earlier writings for publication (which was never accomplished), he says:

. . . We really visited comparatively little of the Park, yet from a spur of what is now called Electric Peak, we had a fine view of much of it and in returning on the west side of the Yellowstone through its second cañon we explored the route which has been followed by nearly all others, and which is now the main route to the Headquarters of the Park.

In closing the letter in which he forwarded an account of the foregoing exploration to the Norris Suburban, [70] Norris mentioned the choice which he had to make with regard to his activities that summer:

Shall soon decide whether General Washburn, Surveyor General of this Territory, friend Everts and Judge Hosmer, once of Toledo, Major Squier, the Bottlers and our humble self join in another expedition to the unexplored region of the Yellowstone Lake. If so, shall go no farther west this season; if not, shall try to cross the mountains to Oregon, down to Columbia, then to California, and return in autumn.

A footnote to the published letter completes the story. In it Norris adds:

I returned from Missoula to Helena August 1st, 1870, finding Gov. Ashley (who had been active for the Yellowstone expedition), removed, the new Governor (Potts), not arrived, Hauser, Langford and other prominent friends of the enterprise absent, [71] and very little prospect of exploration that year, while the N. P. R. R., and other surveying parties down the Columbia promised various benefits in that direction. With no time to waste in deliberation, I chose the latter, returned to Missoula, assisted in surveying my own and other interests there, and then down the Columbia.

After a month's isolation from news of the outside world, I was intensely mortified to learn that Messrs. Langford's Hauser, and others had returned and gone up the Yellowstone, and at San Francisco also learned that friend Everts was lost near the head of Yellowstone Lake, and though after 37 days of such exposure, starvation and suffering as probably few if any other human beings ever survived, he was found by Baronette and Prichette; yet his horse (the one he used on our return from Fort Ellis), his gun, equipments, and entire outfit, including my map, notes, etc., left with him, were totally lost, and no trace of them has ever been, or perhaps ever will be found.

Having thus, by unforeseen accidents and circumstances not especially the fault of myself or of others, failed in my long cherished hope of a prominent record among the first explorers of the Yellowstone Park, [72] and overtasked with business at home, it was not until 1875 that I again reached my Bottler friends. . . . [73]

Nathaniel P. Langford could not have reached Helena, Mont., before the evening of July 28, and, with a stopover at Virginia City, his arrival could have been later; thus, his statement, "About the 1st of August 1870, our plans took definite shape, and some 20 men were enrolled as members of the exploring party," [74] indicates that he arrived with a matured plan which was embarked upon with little or no delay. He adds:

About this time the Crow Indians again "broke loose," and a raid of the Gallatin and Yellowstone valleys was threatened, and a majority of those who had enrolled their names, experiencing that decline of courage so aptly illustrated by Bob Acres, suddently found excuse for withdrawal in various emergent occupations.

There was a scare about that time, but it seems to have resulted more from the presence of Sioux and Blackfoot Indians near the settlements than from any disposition of the Crows to be unfriendly. The following letter written by 1st Lt. E. M. Camp, who commanded the small guard of soldiers stationed at the Crow Agency (Fort Parker, east of present Livingston, Mont.), clarifies the situation:

Both Sioux and Blackfeet have often been seen near the agency, and there is danger of an attack from them at any time. Both tribes being hostile to whites and Crows. The agency is located Thirty-five (35) miles from Fort Ellis. Wild Country intervening. The Guard at present Consists of one (1) Sergt two (2) Corpls and ten (10) Privates from Co. A 7th U.S. Infantry. [75]

An unsettling note had been struck earlier by the post commander at Camp Baker, who had reported bands of Piegans and River Crows near that place. Both "are believed to be friendly but it is possible some of their young men may commit depredations." [76] Given such tensions, no more than a rumor was required to alarm the fainthearted.

According to Langford:

After a few days of suspense and doubt, Samuel T. Hauser told me that if he could find two men whom he knew, who would accompany him, he would attempt the journey; and he asked me to join him in a letter to James Stuart, living at Deer Lodge, proposing that he should go with us. Benjamin Stickney, one of the most enthusiastic of our number, also wrote to Mr. Stuart that there were eight persons who would go at all hazards and asked him (Stuart) to be a member of the party. Stuart replied to Hauser and myself as follows: [77]

"Deer Lodge City, M.T. Aug. 9th, 1870.

"Dear Sam and Langford:

"Stickney wrote me that the Yellow Stone party had dwindled down to eight persons. That is not enough to stand guard, and I won't go into that country without having a guard every night. From present news it is probable that the Crows will be scattered on all the headwaters of the Yellow Stone, and if that is the case, they would not want any better fun than to clean up a party of eight (that does not stand guard) and say that the Sioux did it, as they said when they went through us on the Big Horn. [78] It will not be safe to go into that country with less than fifteen men, and not very safe with that number. I would like it better if it was a fight from the start; we would then kill every Crow that we saw, & take the chances of their rubbing us out. As it is, we will have to let them alone until they will get the best of us by stealing our horses or killing some of us; then we will be so crippled that we can't do them any damage.

"At the commencement of this letter I said I would not go unless the party stood guard. I will take that back, for I am just d- -d fool enough to go anywhere that anybody else is willing to go,—only I want it understood that very likely some of us will lose our hair. I will be on hand Sunday evening, unless I hear that the trip is postponed. Fraternally Yours,

Jas. Stuart

"Since writing the above, I have received a telegram saying, 'twelve of us going certain.' Glad to hear it,—the more the better. Will bring two Pack horses and one Pack saddle."

Meanwhile, Henry D. Washburn had written Lt. Gustavus C. Doane, an officer of the Second United States Cavalry stationed at Fort Ellis, concerning his interest in the proposed exploration. [79] The answer, which could not have reached Helena before August 14th, advised,

Your kind favor of the 9th ult.—came yesterday—and I reply—at the first opportunity for transmittal. Judge Hosmer was correct as regards my earnest desire to go on the trip proposed—but mistaken in relation to my free agency in the premises. To obtain permission for an escort will require an order from Genl Hitchcock [sic]—authorizing Col Baker—to make the detail.

If Hauser and yourself will telegraph at once on rec't to Genl Hitchcock at Saint Paul, Minn.—stating the object of the expedition &c and requesting that an order be sent to the Comdg officer at Fort Ellis, M. T. to furnish an escort of An Officer five men—it will doubtless be favorably considered—and you can bring the reply from the office when you come down or send it before—if answer comes in time Col Baker has promised me the detail if authority be furnished. And by your telegraphing instead of him—the circumlocution at Dist Hdqrs will be obviated I will reimburse you the expense of the messages which should be paid both ways to insure prompt attention.

I will be able to furnish Tents and camp equipage better than you can get in Helena—and can furnish them without trouble to your whole party.

Hoping that we can make the trip in company. . . . [80]

The wise advice of Lieutenant Doane was taken, for Langford later wrote:

About this time Gen. Henry D. Washburn, the surveyor general of Montana, joined with Mr. Hauser in a telegram to General Hancock, at St. Paul, requesting him to provide the promised escort of a company of cavalry. General Hancock immediately responded, and on August 14th telegraphed an order on the commandant at Fort Ellis, near Bozeman, for such escort as would be deemed necessary to insure the safety of our party. [81]

General Hancock's telegram (sent to Col. John Gibbon at Fort Shaw, on August 15) authorized the expedition in these words:

The Surveyor General of Montana, H. D. Washburn, wishes to determine location of Lake and Falls of Yellowstone and asks for a small escort of an officer and five or ten men. I have no objections to this and would like to have an intelligent officer of cavalry who can make a correct map of the country go along, but the escort should be strong, about a company of cavalry—If there is no obstacle to such an expedition other than is known to me, you can order a company or more from Major Baker's command for this service and suggest to him to go along if he thinks proper and to take charge of the conduct of the expedition unless you desire to go yourself. [82]

The Surveyor General was informed the same day by a telegram stating:

Will send orders to Col. Baker for your escort by Wednesday's mail under cover to you at Helena, so you can take them with you to Ellis. Col. Baker will furnish the escort if he has men to spare. I presume he has them. [83]

The plans of the expeditioners had already appeared in the Helena Daily Herald, [84] where it was noted:

Monday morning at eight o'clock, is the time set for the departure of the long talked of Yellowstone Expedition. The roll has been called, thus far the following gentlemen from Helena have answered to their names promptly, and given an affirmative response: Hon. H. D. Washburn, Surveyor General of the Territory, Hon. N. P. Langford, Hon. Truman C. Everts, late Assessor of Internal Revenue, [85] M. F. Truett, Judge of the Probate Court, Sam'l T. Hauser, President of the First National Bank, Warren C. Gillette, Esq., Cornelius Hedges, Esq., Benjamin Stickney and Walter Trumbell [sic]. Deer Lodge will be represented in the person of James Stuart, of the well known mercantile firm of Dance, Stuart & Co., who has become quite famous in the mountain country as a daring and successful Indian fighter. Boulder Valley, (we are informed by Mr. Langford) will be represented by J. M. Greene, who will join the expedition at Bozeman City. At Fort Ellis, the party will be strengthened by a military escort, consisting of Lieutenant Doan [sic] and twelve men. At the Yellowstone Agency, the party will probably receive another small reinforcement, as Capt. E. M. Camp has signified his intention of going through with the expedition. As a great portion of the country through which they will traverse is claimed by the hostile Sioux, the expeditionists will likely encounter some of these bands of roving Indians, and while it is proper to exercise all necessary precaution against unforseen dangers, we apprehend no serious troubles from this source. It will be remembered, however, that Stuart and his party, during their trip to these almost unexplored regions, in 1863, had a most desperate fight with a band of indians, supposed to have been Crows, which outnumbered them five to one, and it was only by good luck and good generalship combined, that they were saved from a terrible fate. One of the party, we believe was killed in the engagement and two others mortally wounded. We merely refer to this event in order that every man who contemplates this long and dangerous trip, may be prepared for any emergency that may rise. General H. D. Washburn, we understand, has been chosen as commander of the expedition. [86] The General will make a safe and trusty leader, and if it becomes necessary to fight the Indians, he will always be found at the post of duty.

P.S. Since the above was in type, we learn the time for departure has been postponed until Wednesday next [17th], one of the party—Mr. Stuart of Deer Lodge, having business that will detain him until then.

On the 16th, the same newspaper noted that Colonel Gibbon's telegram authorizing a military escort had been received, adding: "The Herald, which will send a reporter along, will furnish its readers with important letters from various points as opportunity and the limited facilities for transmission will afford." [87]

The departure of the expedition from Helena had been set for 9 a.m. on Wednesday, August 17, but difficulties with the pack stock caused a delay noted thus by the Herald:

It was not until two o'clock yesterday afternoon, when the Yellowstone exploring party took their departure from the rendezvous on Rodney street, and even then all did not get off. Several of the party, we are informed, were "under the weather" and tarried in the gay Metropolis until "night drew her sable curtain down," when they started off in search of the expedition. The party expected to make their first camp about twenty miles from the city. [88]

Cornelius Hedges, who was really not an outdoors person, characterized the start as a "dismal day of dust, wind and cold," [89] while Samuel T. Hauser put it this way in his rudimentary diary: "considerable bother getting off—started 1 p.m.—3 packs off-within 300 yards—sent back for a second pack[er]—Left packers and Darkeys." [90] He also identifies one of the revelers left behind when the main party cantered out of town about 4 in the afternoon; following Ben Stickney's name in his roster of the expedition's personnel, Hauser added, "tight." The other—from his absence from Hedges' list of those who went together to the "half-way house" run by Nick Greenish 4 miles from Helena—could only have been Jake Smith.

After a night during which Hedges "Didn't sleep at all—dogs bothered," the party reached Vantilburg's by noon, and as it "Started in snowing just as we got in, voted to stay." Hedges' diary also contains this confession: "I felt very sore and was glad of rest." Of this layover, Hauser noted: "All playing cards."

An early start the following morning got them to Major Campbell's by 2:30 p.m., where dinner was ordered at once. Gillette says:

. . . but the shrewd old man kept us waiting till 6 O clock in order to compell [sic] us to stay all night. There was much growling from hungry men but a good supper of chicken & trout, good coffee & cream, with a desert of blanc-mange restored the party to its former good humor. [91]

Langford, who had pushed on alone, reached Bozeman about 7 p.m. on the 19th, which gave him time to arrange with Major Baker for their escort before the other expeditioners arrived the following day. [92] The party put up at the Guy House, and entered upon a lively evening which included a cold supper provided by the proprietors of the firm of Willson & Rich. Gillette thought they were "nine pretty rough looking men to come into the presence of three fine ladies," and Hedges was "much embarrassed" because all had white collars but himself. Afterward, Langford and Hedges called at Gallatin Lodge No. 6 of the Masonic Order, where Langford, as Grand Master, placed the charter in arrest as the best means of ending a grievous dispute. Then everyone went to the Guy House for champagne and musical entertainment at the rooms of Captain and Mrs. Fiske.

Cornelius Hedges described Sunday the 21st as "all commotion, running around, saying goodbye, talking with Masons. Sperling gave box of cigars. Everyone kind, with many good wishes." He also noted:

Went out to camp near Fort & cook our dinner. Lieut Doane brought us a big tent & helped us put it up. shelter from wind, sun & cold. . . . Unpacked our things to get what we wanted. read papers. Jake Smith opened a game & got busted in a few moments. [93] visted by several prospectors who tell us much about the country.

Hedges' mood had changed for the better as the day of departure from Fort Ellis arrived, perhaps as a consequence of that "fine bed and sleep," and the gaiety of that "merry company." He also recorded a note of dissent that would reappear occasionally: "Smith is disgusted at prospect of standing guard," then penned a last-minute dispatch to the Herald, [94] and the Yellowstone Expedition was ready to enter the wilderness.

The official report prepared by Lt. Gustavus C. Doane immediately following the return of the expedition is the best account written by a member. [95] Therefore, the details that follow have been taken from his report unless otherwise noted.

Doane's report, which is prefaced by an extract from Special Order No. 100, issued at Fort Ellis, Montana Territory, August 21, 1870, begins:

In obedience to the above order, I joined the party of General H. D. Washburn, in-route for the Yellowstone, and then encamped near Fort Ellis, M.T. with a detachment of F. Co 2d Cavalry, consisting of Sergeant William Baker, Privates Chas. Moore, John Williamson, William Leipler and George W. McConnell.

The detachment was supplied with two extra saddle horses, and five pack mules for the transportation of supplies. A large pavillion tent was carried for the accommodation of the whole party, in case of stormy weather being encountered; also forty days rations and an abundant supply of ammunition.

The party of civilians from Helena consisted of General H. D. Washburn, Surveyor General of Montana, Hon. N. P. Langford, Hon. T. C. Everts, Judge C. Hedges of Helena, Saml T. Hauser, Warren C. Gillette, Benj C. Stickney, Jr., Walter Trumbull, and Jacob Smith, all of Helena, together with two packers, and two cooks. [96]

They were furnished with a saddle horse apiece, and nine pack animals for the whole outfit: They were provided with one Aneroid Barometer, one Thermometer, and several pocket compasses, by means of which observations were to be taken at different points on the route.

The route from Fort Ellis was the same as that followed by the Folsom party the previous year, with the first encampment on Trail Creek, about 15 miles from the Post. [97]

On the second day, August 23, 1870, the party made 20 miles, which brought them to the Bottler Ranch. The only incident the lieutenant found worth noting was the sighting of a few Indians, who were casually dismissed with the entry, "In the afternoon we met several Indians belonging to the Crow Agency 30 miles below." [98]

Rain began in the evening, so that the pavillion tent had to be put up near the Bottler cabin. [99]

The weather cleared the following morning and camp was moved up the river to a pleasant place below what Doane called "the lower cañon" [100]—present Yankee Jim Canyon, which is really the second canyon going upstream, and was so called until the mid-eighties. It was evident they were in Indian country, so guards were posted and the horses were picketed or hobbled.

On the 25th, the party made their way through Yankee Jim Canyon on a difficult Indian trail, [101] then debouched into an arid valley. Continuing on the west bank of the Yellowstone, they past that "Red Streak Mountain" some prospectors had earlier thought to contain cinnabar, [102] to an encampment at the mouth of Gardner River. [103] Doane called this "our first poor camping place, grass being very scarce, and the slopes of the ranges covered entirely with sage brush," and he added, "From this camp was seen the smoke of fires on the mountains in front, while Indian signs became more numerous and distinct." [104]

The route on the 26th followed what would later be known as the "Turkey Pen Road," and Lieutenant Doane, Everts, and Private William son went ahead as an advance party. Contact with the main group was soon lost due to the latter's difficulty with pack animals made nervous by smoke from the burned-over area on Mount Everts. Thus, the train was unable to follow Doane through to Tower Fall, but had to camp for the night on what Langford called "Antelope Creek"—present Rescue Creek— but which was designated more accurately by Hauser as "Lost Trail Creek," because they lost Doane's trail near the marshy pond on that stream.

Doane, who was following the trail of two "hunters" (probably miners from nearby Bear Gulch), [105] had turned south in order to get on the Bannock Indian trail which passed directly over the Blacktail Deer Plateau, well back from the nearly impassable "middle cañon." [106] That heavily used trail led the advanced party to the first thermal springs on their route—a tepid, sulphurous outflow near present Roosevelt Lodge—and on to Warm Spring Creek, [107] where they camped with the hunters they had been following.

The next day, August 27, while waiting for the main party to come up, Doane had an opportunity to examine the hot springs scattered along the Yellowstone from the mouth of Tower Creek nearly to the entry of Lamar River, and he had time to contemplate the chief feature of the locality, Tower Fall, [108] which he typified in these words:

Nothing can be more chastely beautiful than this lovely cascade, hidden away in the dim light of overshadowing rocks and woods, its very voice hushed to a low murmur unheard at the distance of a few hundred yards. Thousands might pass by within half a mile and not dream of its existence, but once seen, it passes to the list of most pleasant memories.

The remainder of the party arrived that afternoon, and it was decided there was enough to see in the vicinity to justify a layover; thus, a pleasant camp was established where the party remained during the 28th. [109] It was there that the felon on Lieutenant Doane's right thumb was first opened, "three times to the bone, with a very dull knife," in the hope of providing him with relief from his "infernal agonies," but without success. [110]

On August 29, the party broke camp and proceeded toward the falls of the Yellowstone by the route General Washburn had pioneered the previous day. [111] Those who went to the summit of Mount Washburn took a reading from which Doane computed the elevation as 9,966 feet above sea level. [112]

It was while passing over the Washburn Range that these explorers were at last convinced they were entering a land of wonders. Of the view from Dunraven Pass, Doane wrote:

A column of steam rising from the dense woods to the height of several hundred feet, became distinctly visible. We had all heard fabulous stories of this region and were somewhat skeptical as to appearances. At first, it was pronounced a fire in the woods, but presently some one noticed that the vapor rose in regular puffs, and as if expelled with a great force. Then conviction was forced upon us. It was indeed a great column of steam, puffing away on the lofty mountainside, escaping with a roaring sound, audible at a long distance even through the heavy forest.

A hearty cheer rang out at this discovery and we pressed onward with renewed enthusiasm.

Camp was made that evening on the stream that drains most of the southern side of Mount Washburn, [113] and the evening was spent investigating several prominent thermal features nearby. [114] This exploration took them to the rim of the Grand Canyon, which Doane likened to "a second edition of the bottomless pit."

The move made the following day was short—only 8 miles, to a campsite on the lower edge of the meadows on Cascade Creek. With much of the afternoon left for exploring, the members of the party made their way toward the falls singly and in small groups. [115] The views obtained convinced all that there was enough more to see that they were warranted in again laying over a day. Accordingly, the last day of August was also passed in exploring the locality.

Langford proceeded to measure the drop of both the Upper and Lower Falls of the Yellowstone by the same method the Folsom party had used in 1869, and with an identical result at the Upper Fall. [116] Hauser and Stickney managed to scramble down into the Grand Canyon 2-1/2 miles below the Lower Fall, [117] while Lieutenant Doane and Private McConnell climbed down to some hot springs bordering the river a mile farther down the canyon. Hedges, who was less active, spent several hours viewing the Lower Fall, then wandered along the canyon rim until filled with "too much and too great satisfaction to relate." It was Doane's opinion that:

Both of these cataracts deserve to be ranked among the great waterfalls of the continent. No adequate standard of comparison between such objects, either in beauty or grandeur can well be obtained.. . [but] In scenic beauty the upper cataract far excels the lower; it has life, animation, while the lower one simply follows its channel; both how ever are eclipsed as it were by the singular wonders of the mighty cañon below.

The expedition left the camp on Cascade Creek on September 1, moving southward through Hayden Valley. In contrast to the wild flood which foamed powerfully through the Grand Canyon, the Yellowstone River, where it flows through the grasslands created by the shrinkage of Lake Yellowstone, is slow-flowing and sedate—described by Doane in these words: