|

THE BATTLE OF COLD HARBOR

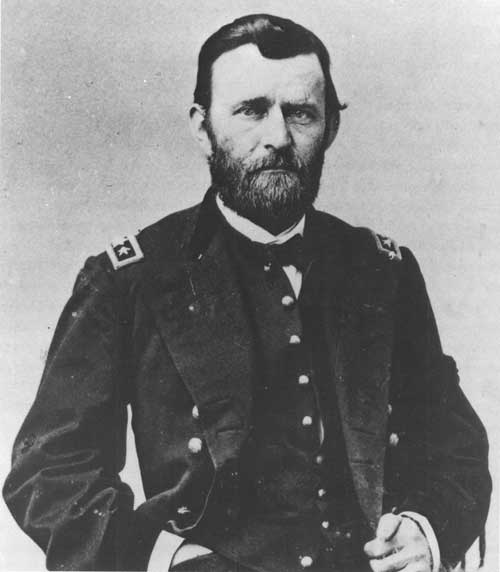

In March 1864, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant became commander

in chief of the Union war effort. He had won impressive victories in the

war's western theater, capturing Vicksburg and driving the Confederate

Army of Tennessee from its mountain fastness near Chattanooga. President

Abraham Lincoln hoped that Grant could impart his western tenacity to

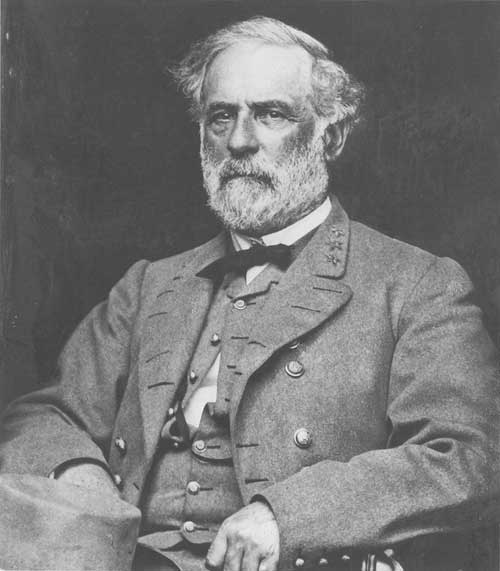

the East, where General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia

boasted a string of successes.

As spring opened in 1864, Lee's army, numbering 65,000 men, held a

fortified line below the Rapidan River, near Orange Court House. Facing

Lee from the Rapidan's northern bank was the Army of the Potomac,

100,000 strong, commanded by Major General George G. Meade. Grant's

objective was the destruction of Lee's army, and he devised a

concentration of Federal forces to accomplish that end. He brought Major

General Ambrose E. Burnside's Ninth Corps, containing 20,000 soldiers,

to join Meade in a mighty host that would cross the Rapidan east of Lee

and bring the Southerner to battle. Simultaneously, the 30,000-man Army

of the James under Major General Benjamin F. Butler was to sally up the

James River and threaten Richmond, the Confederacy's capital, from the

rear. A third expedition headed by Major General Franz Sigel was to

slice south through the Shenandoah Valley west of Lee and threaten the

Confederates' left flank.

On May 4, 1864, Grant set his armies in motion, initiating a series

of engagements covering forty days that have come to be called the

Overland Campaign. He accompanied the main force under Meade, which

created an awkward command situation. Grant viewed his role as

formulating general policies for the Union armies and leaving tactical

decisions to theater commanders. He favored bold attacks and maneuvers,

however, while Meade felt more comfortable waging set-piece battles.

Their approaches to fighting Lee were incompatible, and friction was

inevitable. Burnside, who had formerly headed the Army of the Potomac,

outranked Meade, making it awkward for him to serve under the army

commander. Grant's solution was to act as middleman between Meade and

Burnside, issuing orders directly to the Ninth Corps and coordinating

the two forces.

Crossing below the Rapidan into a thickly wooded region known as the

Wilderness of Spotsylvania, Grant dropped his guard and fell prey to a

surprise attack by Lee. During May 5 and 6, the armies fought viciously

and sustained 30,000 casualties. Bogged down in heavily wooded terrain,

Grant shifted south toward the cross-roads hamlet of Spotsylvania Court

House in an attempt to interpose between Lee and Richmond. Soldiers and

ambulances clogged the roads, and superb Confederate delaying tactics

thwarted the advance. On May 8, Lee intercepted Grant and constructed a

strong defensive line above the courthouse town.

Unable to maneuver past Lee, Grant initiated a welter of offensives.

On May 10, he attacked Lee's left flank on the Po River but was

frustrated by Lee's adroit shifting of troops. That evening, he launched

an army-wide assault against Lee's front hoping to find a weak point.

Lee defeated the disjointed attacks piecemeal. On May 12, Grant

assaulted a weak sector of Lee's formation dubbed the Mule Shoe and

breached Lee's defenses, but rebel units handpicked by Lee fended off

Grant's assaults until the Southerners could prepare a new defensive

line. The Battle of the Bloody Angle, as the slugging match came to be

called, generated another 17,000 casualties with no tangible benefits to

either army. The next morning saw Lee entrenched more securely than

ever. During May 14, Grant tried to turn Lee's right flank, but heavy

rains transformed roads into quagmires and fatally slowed Grant's

columns. For several days, the armies jockeyed for position. On May 18,

Grant assaulted across the Mule Shoe, but Confederate artillery

decimated the Federals before they could reach Lee's new line. Grant's

efforts at Spotsylvania Court House had come to naught.

Two weeks of vicious fightng had

mauled both antagonists. Grant had lost about 36,000 men in combat and

had dispatched his cavalry on an expedition toward Richmond, which left

him short of horsemen to probe Lee's defenses.

|

Two weeks of vicious fighting had mauled both antagonists. Grant had

lost about 36,000 men in combat and had dispatched his cavalry on an

expedition toward Richmond, which left him short of horsemen to probe

Lee's defenses and shield his own movements. He had received, however,

some 17,000 reinforcements, which gave him a total of 90,000 foot

soldiers. For his part, Lee had lost over 20,000 troops in combat and

had sent away three cavalry brigades, numbering perhaps 3,500 men, which

left him slightly over 40,000 men to oppose Grant's 90,000. But Lee's

prospects for reinforcements were good. On May 15, Major General John C.

Breckinridge defeated Sigel at New Market, and the next day, General

Pierre G. T. Beauregard repulsed Butler at Drewry's Bluff. These

victories freed Breckinridge to join Lee and enabled Beauregard to

release Major General George E. Pickett's division and other elements

from Richmond. Altogether, Lee could expect 15,000 seasoned soldiers

during the coming week, raising his numbers to 55,000.

|

WHILE THE FIGHTING IN THE WILDERNESS PRODUCED HEAVY CASUALTIES, THE

FIRES THAT CLAIMED THE LIVES OF MANY WOUNDED WOULD FOREVER LEAVE A

LASTING IMPRESSION ON THE SURVIVORS. (BL)

|

Facing stalemate at Spotsylvania

Court House, Grant decided to abandon frontal attacks and undertake a

maneuver similar to the one he had employed after the

Wilderness.

|

Facing stalemate at Spotsylvania Court House, Grant decided to

abandon frontal attacks and undertake a maneuver similar to the one he

had employed after the Wilderness. By knifing south toward Richmond, he

hoped to force Lee to abandon his earthen fortifications and move onto

open ground. Grant's objective was the North Anna River, a stream

coursing west to east about 25 miles below Spotsylvania Court House.

Hanover Junction, immediately below the river, was an important rail

center. It was here that the Virginia Central Railroad, from Staunton,

and the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad, from

Fredericksburg, intersected. By seizing the river and rail junction,

Grant stood to deprive Lee of his next defensive line and sever the rail

network supplying the rebel army.

If Lee accepted the invitation, Grant

would pounce on him with his three remaining army corps. If Lee

demmurred, Grant would lose nothing.

|

Grant's direct route to the North Anna lay along Telegraph Road. A

few miles east of Telegraph Road, the Ni, Po, and Matta Rivers joined to

form the Mattaponi River, which curved south. Grant recognized that by

marching east and then veering south along the curve of the Mattaponi,

he could use the river to shield him from surprise attacks by Lee. As

Grant matured his plan, he hit upon an intriguing wrinkle. Rather than

staking everything on a race to the North Anna, what if he sent a single

corps south along the rail line? Might not Lee leave his earthworks and

attack this inviting target? If Lee accepted the invitation, Grant

would pounce on him with his three remaining army corps. If Lee

demurred, Grant would lose nothing, as his advanced component would

still enjoy a considerable head start toward the North Anna. Grant

decided to try the venture. For bait, he selected the Potomac Army's

Second Corps, headed by his ablest field commander, Major General

Winfield S. Hancock.

|

LIEUTENANT GENERAL ULYSSES S. GRANT (NA)

|

|

GENERAL ROBERT E. LEE (LC)

|

|

|