|

JUNE 3: GRANT ATTACKS AGAIN AT OLD COLD HARBOR

At 4:30 A.M., Federal troops in front of Cold Harbor lunged through a

thick ground fog toward Lee's bristling earthworks. In minutes, massed

Confederate firepower generated enormous casualties and pinned the

attackers in place. Details varied along the line, but overall, the

repulse was catastrophic.

Of Grant's forces, Hancock's corps, anchoring the lower Union flank,

came closest to succeeding. The corps pushed into the fog toward Turkey

Hill, Brigadier General Francis C. Barlow on the left, Gibbon on the

right, and Birney in reserve. Barlow overran Breckinridge's picket line,

mounted a gentle ridge, and managed to punch through a portion of

Breckinridge's front line and repulsed the defenders in a vicious bout

of hand-to-hand fighting. "Clubbed muskets, bayonets, and swords got in

their deadly work," a Union soldier recalled. Soon the first line of

Confederate entrenchments lay in Northern hands, along with several

hundred prisoners and at least four cannon. The gain, however, proved

short-lived. Brigadier General John R. Brooke, whose brigade had

spearheaded the breakthrough, fell seriously wounded, as did his

replacement. An unexpected swamp threw Gibbon's division on Brooke's

right into confusion, and the supporting troops that Brooke's men had

been anticipating never materialized. Concentrated fire from Confederate

artillery massed on Brooke's left tore into the brigade. The captured

works were quickly becoming a death trap for the Federals.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

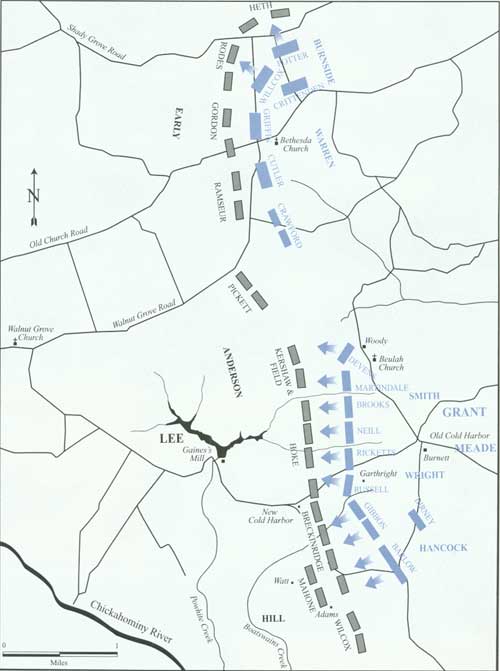

A KILLING GROUND: JUNE 3, 4:30-8 A.M.

In the early morning of June 3, Grant's planned assault against Lee's

position finally moves forward. Following a thirty-six-hour delay,

Grant's attack along Lee's nearly seven miles of entrenchments holds

little chance for success. On Lee's right, Hancock's corps manages to

penetrate the Confederate line, only to be thrown back by a determined

counterattack. In the center, Wright stumbles forward in a lackluster

attack that gains little ground, while Smith suffers tremendously from

flanking fire resulting from Wright's sluggish advance and a lack of

support from Warren, who claims he cannot move forward. On Lee's far

left Burnside gets off to a slow start but finally gets within a few

yards of the Confederate trenches before being stopped. By 8:00, the

Union assault has spent its momentum and Grant's men take shelter

wherever they can find it, in some areas within mere yards of the

Confederate line.

|

|

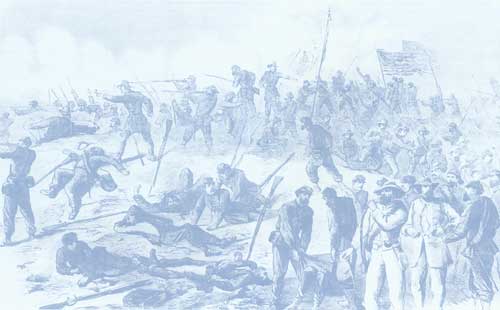

THE ONLY BRIGHT MOMENT OF THE ARMY OF THE POTOMAC ON JUNE 3 WAS ALONG

HANCOCK'S FRONT. IN FIGHTING ITS WAY TO THE CONFEDERATE LINES, THE 7TH

NEW YORK HEAVY ARTILLERY BRIEFLY MANAGED TO CAPTURE SOME OF THE REBEL

WORKS. (NPS)

|

The delay proved fatal, Breckinridge had posted Brigadier General

Joseph Finegan's Floridians and the 2nd Maryland in reserve. Tucked in a

hollow behind Turkey Hill, they witnessed the collapse of the line in

their front. Crying, "Get ready men! Fall into line and charge!" the

fiery Finegan led them into the fray. Brooke's unsupported troops saw

the Floridians and Marylanders coming. "We had lost all semblance of

organization—a veritable mob with no means to turn the captured

guns upon the enemy," recollected a soldier in the 7th New York Heavy

Artillery of Brooke's brigade. "Green soldiers though we were," he

added, "our short experience had taught us to know just when to run, and

run we did, I assure you." They tumbled back from their lodgment in the

Confederate line, sustaining severe casualties.

Gibbon's men meanwhile found themselves in a terrible predicament as

the swamp disordered their alignments and made them vulnerable to fire

from Confederates on the ridge line ahead. Brigadier General Robert O.

Tyler, heading a brigade, fell seriously injured, and Colonel H. Boyd

McKeen, commanding another brigade, was killed. A few isolated pockets

of Northern men reached the Confederate line but were quickly expelled.

Gibbon's advance ground to a halt as his soldiers cursed their superiors

for failing to reconnoiter the path of the attack. "We felt it was

murder, not war, or at best that a very serious mistake had been made,"

a New Yorker complained. "There was a marsh in front of our regiment

and I doubt if we could have reached the enemy works even if they had

not been there to oppose us."

|

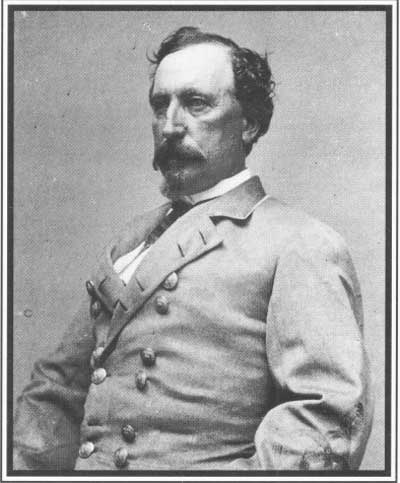

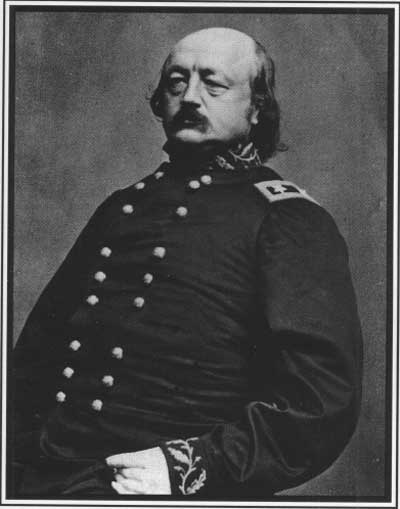

BRIGADIER GENERAL JOSEPH FINEGAN, COMMANDING A BRIGADE OF FLORIDIANS,

PERSONALLY LED THE COUNTERATTACK THAT SEALED THE BREACH IN THE

CONFEDERATE LINES AND THREW BACK HANCOCK'S MEN. (WESTERN RESERVE

HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

North of Gibbon a veritable blizzard of lead swept Wright's Sixth

Corps and pinned it in place. The Sixth Corps' soldiers were in no mood

to repeat their disastrous charge of June 1 and contributed virtually

nothing to the Federal effort this bleak morning. From their slightly

forward position, many of Wright's men could look to their left and watch

the Confederates slice down Hancock's soldiers like "mown grass." Even

the bellicose Upton deemed an advance "impracticable." Ricketts, whose

division was on Upton's right, sent his men into a "murderous fire" from

Kershaw's entrenched line. A Vermonter recounted that on approaching the

rebel earthworks, his compatriots were "simply slaughtered." Neill's

division, next to Ricketts, suffered a similar fate, being "swept away,"

in the words of a participant. Many Confederates in front of Wright

never realized that a major attack had been made against them. "It may

sound incredible," wrote Brigadier General Johnson Hagood, whose South

Carolinians occupied much of the works across from the Sixth Corps,

"but it is nevertheless strictly true, that [I] was not aware at the

time of any serious assault having been given."

|

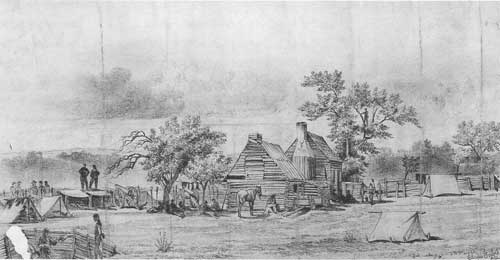

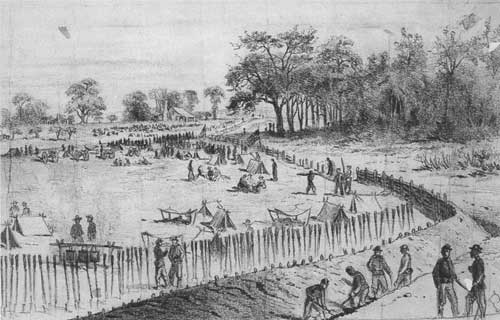

BEHIND HANCOCK'S LINES AT COLD HARBOR. (LC)

|

Elements from Smith's Eighteenth Corps stepped into a killing field

of overlapping rebel musketry and artillery. Manning the rebel

entrenchments in their front were three brigades of Major General

Charles W. Field's division and all of Joseph Kershaw's division. Even

the terrain worked to the advantage of the Confederates and channeled

the advancing Federals into two ravines. Martindale's division charged

through a stretch of woods and emerged into a clearing in front of the

rebel works. Volleys of musketry and artillery fire tore into the

blue-clad ranks. An Alabamian watched in fascination as heads, arms, and

muskets rained down after each discharge. "The men bent down as they

pushed forward, as if trying, as they were, to breast a tempest, and the

files of men went down like rows of blocks or bricks pushed over by

striking against one another," recounted a Union officer. Brooks's

division fared no better. Describing the effect of double canister at

short range, a Confederate described the slaughter as "deadly, bloody

work." Smith rode into the maelstrom and tried to coordinate his units,

but his efforts kept his men exposed to the fire and only increased the

slaughter. A Southerner recalled watching "dust fog out of a man's

clothing in two or three places at once where as many balls would strike

him at the same moment."

|

LIKE HIS COMMANDER GENERAL MEADE, MAJOR GENERAL AMBROSE E. BURNSIDE

(SEATED AT RIGHT) FOUND HIMSELF IN AN AWKWARD POSITION IN THE CHAIN OF

COMMAND, HAVING LED THE ARMY OF THE POTOMAC A YEAR AND A HALF EARLIER AT

FREDERICKSBURG. HE WAS NOW SIMPLY IN CHARGE OF THE NINTH CORPS. (LC)

|

Warren's Fifth Corps, facing Pickett's division, extended the Federal

formation north from Smith's right to Old Church Road. Warren had

developed a strong aversion to attacking entrenched Confederate

positions and did almost nothing. The Confederate First Corps'

artillery commander Alexander took advantage of Warren's quiescence to

focus his guns on the northern end of Smith's corps during its abortive

charges.

Burnside's Ninth Corps anchored the northern end of the Union

formation. Pasting onto Warren, Burnside's line bent northeastward above

Bethesda Church. Facing Burnside was Early's Second Corps and Henry

Heth's division of the Third Corps. Burnside, unlike Warren, stirred to

action later in the morning and launched a powerful assault. He overran

the Confederate skirmishers but was brought up short in front of the

main set of rebel earthworks. Mistakenly believing that he had pierced

Early's first line of works, he halted to regroup and prepare to renew

his attacks early in the afternoon.

Contradictory reports poured into Union headquarters east of Old Cold

Harbor. Uncertainty as to what was happening, in addition to the length

of the Union line, rendered coordination impossible. In desperation,

Smith wrote that his men were "very much cut up" and could not carry

their front unless the Sixth Corps protected their left from a "galling

fire." Wright, however, maintained that he could not advance until Smith

moved, and Warren, on Smith's other flank, voiced a similar complaint.

As coordination dissolved, the Union troops began digging in.

Lee remained at his headquarters near Gaines's Mill, behind New Cold

Harbor, leaving the fighting to his subordinates. When Postmaster

General John H. Reagan rode over from Richmond and inquired about the

severe artillery fire, Lee drew his attention to the musketry, which

sounded like the tearing of a sheet. "It is that that kills men," Lee

informed him. Reagan then asked what reserves Lee had on hand to repel

the Federals if they broke through. "Not a regiment," Lee answered, "And

that has been my condition ever since the fighting commenced on the

Rappahannock. If I shorten my lines to provide a reserve he will turn

me," he observed. "If I weaken my lines to provide a reserve, he will

break them."

|

STRONG LINES OF ENTRENCHMENTS STRETCHED FOR NEARLY SEVEN MILES THROUGH

THE COLD HARBOR AREA. (LC)

|

Still hopeful of smashing Lee's formation, Grant at 7:00 A.M. advised

Meade that if any assault succeeded, "push it vigorously and if

necessary pile in troops at the successful point from wherever they can

be taken." Meade dutifully ordered Wright to "assault at once ...

without reference to [Smith's] advance." He directed Smith to continue

his assault "without reference to General Wright's" and requested

Hancock to "try to do the same" unless he considered further attacks

hopeless. Hancock wrote back advising "against persistence here" and

stayed put. Smith denounced another attack as a "wanton waste of life"

and refused to move. And Wright's soldiers responded simply by

redoubling their musketry. So far as the Union soldiers and field

commanders were concerned, the battle was over. At 12:30, Grant conceded

the inevitable. "The opinion of the corps commanders not being sanguine

of success in case an assault is ordered," he wrote to Meade, "you may

direct a suspension of farther advance for the present."

As the firing subsided, Confederates peered over their earthworks

to view their handiwork. "Men lay in places likes hogs in a pen," a

rebel noted in horror, "some side by side, across each other, some two

deep, while others with their legs lying across the heaad and body of

their dead comrades."

|

As the firing subsided, Confederates peered over their earthworks to

view their handiwork. "Men lay in places likes hogs in a pen," a rebel

noted in horror, "some side by side, across each other, some two deep,

while others with their legs lying across the head and body of their

dead comrades." One of Lee's hardened generals related that he had "seen

nothing to exceed this." Grant's casualties surpassed 6,000 men, Lee's

approached 1,500. The Federals dug trenches with bayonets and cups,

sometimes incorporating bodies into their makeshift earthworks. Any

movement provoked flurries of musketry. "I tell you I hugged the ground

so close that I was no thicker than your hand," a Union soldier

reminisced.

Around 2:00 P.M., Grant wired Washington that his assaults had gained

no "decisive advantage." His losses, he added, were "not severe." Years

later, however, when penning his memoirs on his deathbed, Grant revealed

his true feelings about the debacle. "I have always regretted that the

last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made," he wrote, For his part, Lee

wrote President Davis that "so far every attack of the enemy has been

repulsed." The Confederate loss had been small, he advised, and the

army's success "all that we could expect."

Preparation was non-existent. Battle-weariness and the attrition

of men and commanders at all levels had a telling effect. Each corps

fought its own battle, making no attempt to coordinate with the

others.

|

What had gone wrong? Grant's decision to postpone the attack on June

2 enabled the Confederates to strengthen their defenses. And although

Grant had directed the Union corps commanders to examine the ground and

perfect their plans, they had done neither. Reconnaissance was woefully

lax and failed to disclose important swamps and other terrain features.

Preparation was non existent. Battle-weariness and the attrition of men

and commanders at all levels had a telling effect. Each corps fought its

own battle, making no attempt to coordinate with the others. Grant

apparently expected Meade to supervise the assaults, but Meade remained

strangely passive, perhaps in a misdirected effort to avoid

responsibility for the enterprise. Only the Second Corps and parts of

the Eighteenth and Ninth Corps—perhaps twenty thousand Federal

troops—were actively engaged. The overall picture was that of an

army without a leader.

|

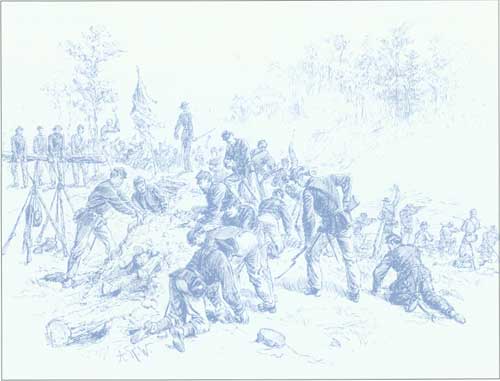

THEIR ATTACKS HAVING BEEN REPULSED, BUT STILL ATTEMPTING TO HOLD THE

GROUND ALREADY GAINED, UNION TROOPS BEGAN CONSTRUCTION OF THEIR OWN

TRENCHES. IN MOST CASES USING NOTHING BUT THEIR BAYONETS AND BARE HANDS.

(NPS)

|

|

AS COMMANDER OK THE ARMY OF THE JAMES, MAJOR GENERAL BENJAMIN F. BUTLER

HAD LITTLE IMPACT ON THE BATTLE AT COLD HARBOR, OUTSIDE OF LENDING

LOGISTICAL SUPPORT AND THE ASSISTANCE OF ELITE EIGHTEENTH CORPS.

(USAMHI)

|

A Confederate later described Cold Harbor as "perhaps the easiest

victory ever granted to the Confederate arms by the folly of the Federal

commanders." Lee realized, however, that the victory was only

temporary. Noting that Butler had weakened his army by detaching the

Eighteenth Corps to Cold Harbor, Lee expressed hope to Davis that

Beauregard might be able to spare additional troops. "No time should be

lost if reinforcements can be had," Lee emphasized. In response,

Richmond ordered Brigadier General Matt W. Ransom's brigade to join

Lee.

The armies lay pressed close together during the night, "almost

within a stone's throw of each other," noted one of Meade's aides, "and

the separating space ploughed by cannon shot, and dotted with dead

bodies that neither side dared bury." He concluded: "Nothing can give a

greater idea of deathless tenacity of purpose than the picture of these

two hosts, after a bloody and nearly continuous struggle of thirty days,

thus lying down to sleep with their hands almost on each other's

throats."

|

|