|

MAY 22-23: GRANT AND LEE MEET AT THE NORTH ANNA RIVER

Lee was awake by 5:00 A.M. on May 22 and issuing orders to his corps

commanders to concentrate below the North Anna. He completed his

maneuver during the day without interference from Grant. When Major

General Jubal A. Early protested that his men were exhausted, the

ordinarily even-tempered Lee snapped back, "You must not tell me these

things, but when I give you an order, see that it is executed!" Weeks of

ceaseless campaigning had exacted their toll. "General Lee is much

troubled and not well," Early observed.

Grant conceded that Lee had won the race and decided not to push his

exhausted troops. He considered swinging past Lee's right flank on roads

farther east but elected instead to follow Lee down Telegraph Road. He

let his men start late and marched them only a few miles. By nightfall,

Warren had camped on Telegraph Road six miles above the North Anna.

Wright had bivouacked a few miles behind, and Burnside had advanced to

New Bethel Church. Hancock remained entrenched on his ridge west of

Milford Station. A short march the next morning would bring the Union

forces to the river.

Grant established headquarters at the Tyler house, near Burnside's

encampment. The Ninth Corps commander visited and inquired of Mrs.

Tyler, "I don't suppose, madam, you ever saw so many Yankee soldiers

before?" Her answer—"Not at liberty, sir"—provoked a round of

laughs at his expense.

On May 23, Warren resumed his march along Telegraph Road, Wright slid

into place behind him, and Burnside began threading along country byways

to move into position behind Wright. Around 9:00 AM., Warren reached Mt.

Carmel Church, two miles above the North Anna, and stopped for

instructions. Hancock's lead elements pulled up, and the two corps

became thoroughly snarled. Federal maps were hopelessly wrong about

which crossings had bridges and which had only fords. It was finally

decided that Hancock would continue along Telegraph Road to Chesterfield

Bridge and Warren would cross the North Anna a few miles upstream at

Jericho Mills.

|

AS COMMANDER OF THE ARMY OF THE POTOMAC, MAJOR GENERAL GEORGE G. MEADE

WAS IN THE DIFFICULT POSITION OF HAVING HIS SUPERIOR, GRANT,

ACCOMPANYING HIM ON THE CAMPAIGN. (LC)

|

|

MAJOR GENERAL WINFIELD S. HANCOCK COMMANDED THE UNION SECOND CORPS AND

WAS ONE OP GRANT'S MOST TRUSTED SUBORDINATES. (BL)

|

Grant and Meade rode sullenly along, scarcely speaking. Relations

between the two generals had reached a low point, as Meade opposed

Grant's plan to move directly on the Confederates, favoring instead a

maneuver around Lee's eastern flank. At one juncture, Meade spurred

ahead in a huff, leaving Grant in his dust. The generals stopped at the

Moncure house, a few miles short of Telegraph Road, and set up

headquarters. Meade wrote his wife that day that he wished to retire

from his "present false position" but saw no choice but to patiently

endure the "humiliation" forced on him by Grant.

Lee incorrectly concluded that Grant's thrust along Telegraph Road

was a diversion to deceive him while the main body of Federals shifted

around his right flank. Acting on this analysis, Lee postponed

fortifying his North Anna line. At Chesterfield Bridge, where Telegraph

Road crossed the river, he left only a small South Carolina brigade

under Colonel John Henagan in a dirt redoubt on the northern bank. The

crossings upriver from Chesterfield Bridge—Ox Ford, Quarles' Mill,

and Jericho Mills—remained almost entirely undefended, and only a

small party guarded the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad

bridge downstream.

Lee's miscalculation presented Grant a superb opportunity. The

Confederate position on the North Anna was exceedingly vulnerable. Fate

seemed willing to make amends for the harsh hand it had dealt the

Federals on May 21. It remained to be seen whether the Union commanders

understood their good fortune and whether they could move quickly enough

to exploit it.

The only Confederates north of Chesterfield Bridge, Henagan's South

Carolinians were precariously situated. Their sole support was Edward P.

Alexander's First Corps artillery, posted on high ground south of the

river. Henagan's men were worried, but Lee considered them safe. After

all, he thought, Hancock's and Warren's deployments were only

feints.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

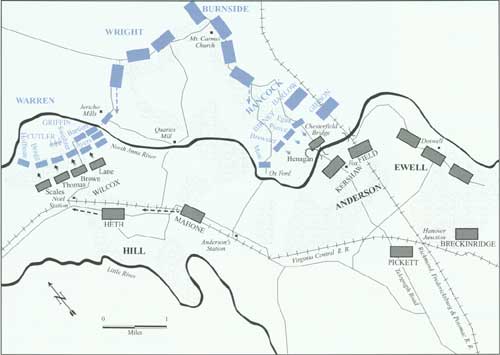

CROSSING THE NORTH ANNA: MAY 23, 6-7 P.M.

In the early afternoon, Grant finds Lee positioned along the North

Anna and defending the crossing at Chesterfield Bridge. Ordering Warren

to cross upstream at Jericho Mills, Hancock is to force a crossing at

the bridge. In the early evening, three brigades from Birney's division,

of Hancock's corps, overwhelm Colonel Henagan's South Carolinians on the

north bank and secure the crossing. Farther upstream, Wilcox's division

of Hill's corps assaults the Union position near Jericho Mills and

nearly routs Warren, but Federal artillery stems the Confederate advance

and with darkness Grant secures his position on the south bank.

|

Hancock pushed south along Telegraph Road, Major General David B.

Birney's division in the fore, until he reached a small creek. At first

he mistook the stream for the North Anna and was elated at having

crossed unopposed. Pressing ahead, Birney came under fire from Henagan's

redoubt and realized his mistake. Birney deployed to attack, forming

Brigadier General Thomas W. Egan's brigade east of the roadway and

Brigadier General Byron R. Pierce's brigade west of Egan. The Second

Corps' artillery arrived and opened on the Confederates. Lee watched

from Thomas Fox's home, a short distance below the river. A Union ball

whizzed near the general and lodged in a door frame. Alexander's guns

answered, and a vigorous artillery duel shook the countryside. A shell

dislodged bricks from the Fox house's chimney and almost killed

Alexander.

A few South Carolinians sprinted to safety over Chesterfield

Bridge, many leaped into the river to swim across, and many were

captured. The rebels tried to set the bridge on fire, but marksmen from

the 93rd New York kept them from the task.

|

At 6:00 P.M., Egan and Pierce, supported by two regiments from

Colonel William R. Brewster's brigade, dashed across a clearing and

swarmed into Henagan's redoubt. Federals stabbed bayonets into the

earthen wall to scale the parapet while others climbed over on their

compatriots' backs. Overwhelmed, Henagan's men fled. "We were soon studying

the pattern of their coat tails," a soldier from Maine recorded,

"and we went in hot pursuit under a pitiless storm of shot, shell, and

we know what not." A few South Carolinians sprinted to safety over

Chesterfield Bridge, many leaped into the river to swim across, and many

were captured. The rebels tried to set the bridge on fire, but marksmen

from the 93rd New York kept them from the task. The bridge was

Hancock's, but he made no attempt to force his way over, as Alexander's

artillery maintained a "fearful fire." Soon Hancock's entire corps was

entrenching along the northern bank.

Warren meanwhile completed his march upstream to Jericho Mills. His

map indicated a bridge, but a ford offered the only way over. Warren

sent a contingent across the river and up the far bank, which rose

steeply to a plateau of woods and fields. Finding the crossing

uncontested, he dispatched Brigadier General Charles Griffin's division

to establish a bridgehead. Pontoons were in place by 4:30 P.M., and soon

the rest of the Fifth Corps was filing over. An elderly woman declared

war on a regiment of Massachusetts soldiers. "Gentlemen, why have you

come?" she demanded. "Mr. Lee is not here. You are spoiling my garden."

A Union colonel piped up, "Boys, keep between the rows."

Learning from a prisoner that Hill's Confederates were camped a short

distance ahead at the Virginia Central Railroad, Warren formed battle

lines and began bringing up artillery. Soon the divisions of Crawford

and Griffin, arrayed east to west in that order, crowned the river's

southern bank above Jericho Mills. Warren's remaining division under

Brigadier General Lysander Cutler moved into place on Griffin's

right.

Lee continued to underestimate Warren's threat. "Go back and tell

General A. P. Hill to leave his men in camp," he directed a courier.

"This is nothing but a feint. The enemy is preparing to cross below."

Hill accepted Lee's assessment and dispatched a single

division—Major General Cadmus M. Wilcox's outfit, supported by

Colonel William J. Pegram's artillery—to drive Warren across the

river.

|

DEFENDED BY A MERE HANDFUL OF CONFEDERATES UNDER COLONEL JOHN HENAGAN,

THIS SMALL REDOUBT WAS EASILY OVERRUN BY HANCOCK'S MEN, ALLOWING

FEDERALS TO SEIZE THE CHESTERFIELD BRIDGE, OVER THE NORTH ANNA, INTACT.

(LC)

|

Pegram's opening salvo badly mauled Crawford's Pennsylvania Reserves.

"The air seemed filled with the shrieking shells and whizzing

fragments," a Pennsylvanian observed, adding that "soldiers who had been

through all the battles of the Potomac Army affirmed that they never

experienced such a noisy onset, except at Gettysburg." Then the right

wing of Wilcox's formation, consisting of Brigadier General James H.

Lane's North Carolinians and Brigadier General Samuel McGowan's South

Carolinians (temporarily commanded by Colonel Joseph N. Brown), pitched

into Griffin. Although subjected to a terrible pounding, the Federals

held. Suddenly Wilcox's left wing—composed of Brigadier General

Edward L. Thomas's Georgia brigade, intermixed with some of Brown's

South Carolinians and Brigadier General Alfred M. Scales's North

Carolinians—pushed past Griffin's right and slammed into Cutler,

who was just moving into position. Their impetus fractured Cutler's

line, and the Federals streamed rearward, Confederates in hot pursuit.

With his front crumbling, the river to his back, and no reinforcements

nearby, Warren was in serious danger.

The Fifth Corps' artillery, commanded by the outspoken Colonel

Charles S. Wainwright, saved the day for Warren. As the left half of

Wilcox's line pushed ahead, Wainwright rushed twelve guns to a ridge and

pinned the Confederates in place with plunging fire. Then portions of

Brigadier General Joseph J. Bartlett's brigade, the 83rd Pennsylvania

leading, filtered down a ravine and enfiladed the exposed right flank of

Wilcox's foremost elements. The Georgians broke rearward, expecting

Scales's men to take their place and "whip them out," as a Georgian

later put it. Scales, however, had veered out of position, leaving

Thomas unsupported, and Thomas's withdrawal uncovered Scales's flank.

During the resulting fracas, the Federals captured Colonel Brown and

several hundred prisoners. Lacking reinforcements—another of

Hill's divisions under Major General Henry Heth arrived too late to be

of assistance—Wilcox saw no option but to pull his entire

division back to the Virginia Central Railroad. His losses approximated

seven hundred men.

|

AFTER CROSSING THE NORTH ANNA AT JERICHO MILLS, THE UNION, FIFTH CORPS

NARROWLY AVERTED DISASTER WHEN ATTACKED BY MAJOR GENERAL CADMUS WILCOX'S

CONFEDERATE DIVISION. (LC)

|

|

LIEUTENANT GENERAL AMBROSE P. HILL COMMANDED LEE'S THIRD CORPS DURING

THE CAMPAIGN. FRUSTRATED ABOUT HILL'S FAILURE TO DISLODGE THE UNION

FORCE AT JERICHO MILLS, LEE VERBALLY LASHED OUT AGAINST HIS SUBORDINATE.

(NA)

|

|

CHEATING DEATH ALONG THE NORTH ANNA

Situated along the Telegraph Road, on the southern bank

overlooking the North Anna River, the Parson Fox house, known as

"Ellington," was the scene of some narrow escapes for Northern and

Southern officers. On May 23, the home served as headquarters for both

Major Generals Richard H. Anderson and Joseph B. Kershaw. It was during

thus time that General Lee made a brief stop here and, while under Union

artillery fire from Hancock's guns on the north side of the river, was

nearly struck by a shell that embedded itself in the doorway of the

building. Later that same day, Brigadier General Edward P. Alexander,

who had command of the Confederate artillery stationed near the Fox

house, had a close encounter with the accuracy of Hancock's gunners, an

event that he vividly remembered in his postwar memoir.

During the afternoon I had a very narrow escape. Between the

Telegraph Road & R.R. on the bluff over the valley stream, was a

large two story & basement, square, brick house belonging to Parson

Fox. ... Our batteries were distributed along the bluffs both above

& below, & Gen. Anderson & his staff had stopped in the yard

behind this brick house. I joined them, & being tired sat down

on the sill of a closed basement window, several couriers standing

just in front of me & holding horses. Just then a shell cut off

about ten feet of a chimney top which there ran up in the wall. I could

not jump clear of the bricks as they began to fall for the couriers

& horses were in the way, but as quick as a cat jumped on the sill,

about a foot above the ground, & flattened my back against the

window. The recess was scarcely four inches deep, & the avalanch[e]

of bricks fell so close to me that when they were done falling the slope

of the pile completely covered my feet & ankles, which were badly

bruised. Two couriers lay in the pile, one of them killed. There are a

number of places on that line of R.R. from Richmond to Fredericksburg

which I always like to look at out of the car windows as I go by, even

to this day, & Parson Fox's house is one of them. For I would not

like to have been killed by bricks.

— Excerpt from Fighting for the

Confederacy, courtesy of University of North Carolina Press

Following Hancock's push across the Chesterfield Bridge, on May

24, the Fox house fell into Union hands and became the headquarters for

that general. At this point, the house and grounds became the target of

Southern artillerists, who threw shot and shell at the Union troops

busily engaged in erecting breastworks across the property. Gathering in

the yard, a number of Union generals discussed their situation while the

iron rained down among them. A witness to this event was Captain Charles

A. Stevens of the United States Sharpshooters.

Some of these shells passed through the grove where the regimental

reserve had remained, and where several noted Union generals had

congregated. The central figure of the group was Gen. Hancock, whose tall,

handsome and commanding person looked every inch the brave soldier he

had long before proven himself to be. On his left stood honest, though

sometime unfortunate, Burnside; on the right the gallant division

commander, Birney; while immediately in front facing them was

Crittenden. An earnest consultation took place, the rebel shell passing

occasionally over their heads as if hunting for some body. Of course

they were closely observed by the green-coated riflemen [Berdan's

Sharpshooters], who tried to discern from their looks and gestures,

rather than to hear their low-toned conversation, what was the coming

programme. Finally, they broke up the council and at once repaired to

the house preparatory to mounting and away!—all but Hancock—it

was his headquarters. And not a moment too soon did they leave their

meeting place, for right there is where these four Union generals just

missed death, as they scarcely moved around to the front of the house,

when a searching shell passing through a Sharpshooter's knapsack, landed

in the exact spot they had a moment before occupied, exploding with

terrific force, but luckily harmless.

—Excerpt from Berdan's United States

Sharpshooters in the Army of the Potomac

|

THE FOX HOUSE AS IT APPEARED IN THE 1930S. THE PORCH HAS SINCE

BEEN REMOVED AND THE HOUSE REMAINS A PRIVATE RESIDENCE

TODAY. (LIBRARY OF VIRGINIA)

|

|

The Confederates had managed the battle poorly. Lee had failed to

appreciate the danger, Hill had neglected to support the assault

adequately, and Wilcox had poorly coordinated his brigades. On

encountering Hill the next morning, Lee voiced frustration over the

aborted attack. "Why did you not do as Jackson would have

done—thrown your whole force upon those people and driven them

back?" he chided the commander of his Third Corps.

As darkness descended, Warren threw up earthworks to secure his lodgment

on Lee's side of the North Anna, His corps now formed the right end

of the Union line. Wright passed through Mt. Carmel Church and camped on

the river's northern bank in support of Warren. Burnside shuttled to Ox

Ford on Warren's left and formed north of the river. And Hancock covered

the northern bank from Burnside's left to a point downriver from the

railway trestle. Grant had united his army on the North Anna.

|

ALTHOUGH HE HAD BEEN VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES BEFORE THE WAR,

JOHN C. BRECKINRIDGE SERVED THE CONFEDERACY AS A MAJOR GENERAL.

(BL)

|

Lee had to reconsider his plans. The North Anna was not as defensible

as he had assumed. If he attempted to fortify the river's southern bank,

Warren would enfilade his formation. Near dusk, beneath a large oak in a

forty-acre clearing, Lee met with Ewell Anderson, and an assortment of

engineers. Lee sat on a root, his back against the tree, and entertained

suggestions about how to configure his earthworks. The solution that

evolved was a masterpiece of defensive engineering.

Lee drew his earthworks in the shape of an upside-down V, skillfully

exploiting both the terrain and Grant's penchant for offensive

operations. The tip rested on bluffs commanding Ox Ford, midway between

Jericho Mills and Chesterfield Bridge. The left, or western, leg of the

V slanted southwest along a shallow ridge and anchored firmly on Little

River, a mile and a half to the rear. The V's right, or eastern, leg cut

southeast across a patchwork of woods and fields, covered Hanover

Junction, and terminated behind a swamp. Hill occupied the V's left arm,

while Anderson and Ewell manned the earthworks on the right.

Breckinridge and Pickett remained in reserve on the Virginia Central

Railroad.

Lee labored to make the most of his opportunity. Confederate

engineers worked feverishly all night positioning the Army of Northern

Virginia.

|

Lee's clever deployment invited Grant into a trap. By throwing the

Army of Northern Virginia's wings back from the inverted V's apex, Lee

hoped Grant would assume that the Confederates had retreated and left

behind only a small diversionary force at Ox Ford. Lee anticipated that

Grant would hew to his accustomed pattern and pursue. When the inverted

V bisected Grant's force, Lee would spring his trap, using a small

contingent to hold one keg of the V while concentrating the rest of his

army to defeat the Federals facing the other leg. The beauty of the plan

was that Grant could assist the beleaguered portion of his army only by

laboriously bringing reinforcements across the North Anna, shifting

them past Ox Ford along tortuous roads, then sending them across the

river again. By then, Lee expected to have his victory. In a master

stroke, he had suited the military maxim favoring interior lines to the

North Anna's topography and given his smaller army an advantage over

Grant.

Lee labored to make the most of his opportunity. Confederate

engineers worked feverishly all night positioning the Army of Northern

Virginia. The Southern commander entertained high hopes. "If I can get

one more pull at [Grant,]" he predicted, "I will defeat him."

|

|