|

JUNE 12: GRANT STARTS TOWARD THE JAMES RIVER

On June 12, Lee made a momentous decision. The eccentric, one-legged

Ewell lacked the stamina and aggressive instincts necessary for leading

a corps. Citing the strain that active campaigning imposed on Ewell's

fragile health, Lee recommended the general undertake "some duty

attendant with less labor and exposure," such as supervising the defenses of

Richmond. Jubal Early, who had commanded the Second Corps in Ewell's

absence, assumed permanent command of the outfit. Lee immediately

informed Early that he was to initiate a daring expedition, taking his

corps to the Shenandoah Valley, defeating Hunter, and then sweeping

north in a raid toward Washington. Lee's objective was to divert Grant's

attention to the Valley and the defense of Washington. The scheme was

risky, as Early's departure would seriously weaken the Confederate

lines in front of Cold Harbor. But desperate times called for desperate

measures, and Lee considered the gambit justified as an opportunity to

regain the initiative.

Grant also made momentous decisions on June 12. Around 2:00 A.M., two

of his aides returned from a reconnaissance to the James. They had

plotted routes for the Army of the Potomac to follow to the river. Boats

would ferry a portion of the force across while the remainder marched

over on a massive pontoon bridge. By moving quickly, the Federals could

steal a march on Lee and be well on their way to Petersburg before the

Confederates figured out where they had gone. Grant was elated. He

ordered Meade to leave Cold Harbor that night and begin moving toward

the James.

|

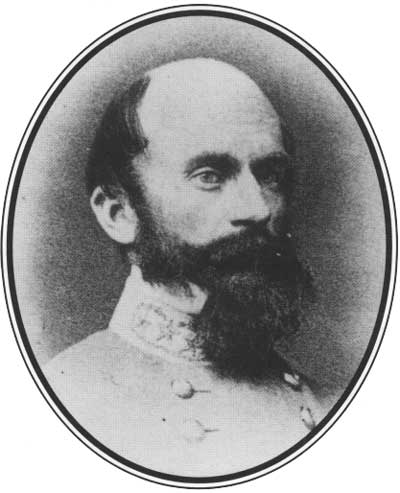

ALTHOUGH HE HAD SHOWN PROMISE EARLIER IN THE WAR, LIEUTENANT GENERAL

RICHARD S. EWELL BECAME A CAUSE FOR CONCERN FOR LEE DURING THE

CAMPAIGN. (LC)

|

Disengaging from the vigilant Lee posed a formidable challenge. The

Federals had to slip from their entrenchments undetected and be well

under way before daylight. To hasten the march, Grant decided to

disperse his corps along different routes. Smith's Eighteenth Corps was

to march east to White House Landing, board transports, and proceed by

river back to Butler, retracing its route of a few days before. The Army

of the Potomac meanwhile would march south. Warren and Hancock were to

cross the Chickahominy River at Long Bridge while Wright and Burnside

crossed a few miles downstream at Jones' Bridge. Wilson's cavalry

division was to accompany the marching columns, one brigade clearing

the way for Warren while the other covered the army's rear.

|

A FINAL RESTING PLACE: COLD HARBOR NATIONAL CEMETERY

On the evening of June 2, Colonel Horace Porter of Grant's staff

found himself, while delivering the final orders for the dawn assault,

passing through the camps of the troops who were to lead the way the

following morning. He would later claim that while on this errand, he

noticed a rather peculiar activity being carried out in one of the

regiments. It appeared as though the soldiers were mending their uniforms,

but upon closer inspection it was seen that the men were actually

sewing slips of paper, bearing their names and home addresses, to their

uniforms. Porter realized that this was being done so that "their dead

bodies might be recognized upon the field, and their fate made known to

their families at home." For many soldiers, like those Porter came

across, the idea of ending up in an unmarked or unknown grave was a

terrific and horrifying way to envision one's fate.

The Battle of Cold Harbor claimed nearly 5,000 lives. For Grant's

army, the costliest day was June 3, when his ill-advised assaults were

brutally repulsed in front of Lee's well-prepared

fortifications.

|

The Battle of Cold Harbor claimed nearly 5,000 lives. For Grant's

army, the costliest day was June 3, when his ill-advised assaults were

brutally repulsed in front of Lee's well-prepared fortifications. Many

of the wounded died from exposure and hunger while they lay between the

opposing lines, still many more succumbed to their mortal wounds at the

overflowing hospitals. Burial of the dead consisted, more often than

not, of hastily dug mass graves on the battlefield or lonely individual

plots near the hospitals. Although some had taken measures hopefully to

ensure their bodies would be identified, few were lucky to have their

grave sites marked, thus making later identification of the men nearly

impossible.

In 1862, Congress made provisions for the creation of national

cemeteries as a final resting place for those who died fighting for the

Union, but it was not until 1866, two years following the battle at Cold

Harbor, that these cemeteries were established in the Richmond area. A

year earlier, in May 1865, a detail of Federal soldiers, accompanied by

agents of the United States Christian Commission and American Bible

Society, traveled to Cold Harbor in an attempt to locate and mark as

many of the Union graves as they could. Many of the headboards erected

by the soldiers remained, and a few of the other graves were identified

through items found buried with the soldiers, such as names found on

clothing, envelopes, and other personal possessions. The following year,

the Federal government established five national cemeteries in the

Richmond area, one of which was located on one and a half acres of

farmland near the Old Cold Harbor crossroads, directly across from the

Garthright house, which had served as a Union hospital. In March 1866,

reburial crews fanned out over a twenty-two-mile area and began the

ghastly process of disinterring the remains of the Union soldiers, many

from the graves that had been located the previous year, and removing

them to the Cold Harbor National Cemetery. The majority of the men

were found on the nearby battlefield of 1864, but many others were taken

from the 1862 battlefields of Beaver Dam Creek, Gaines's Mill, and

Savage's Station. Identification of the men was in most cases simply

impossible. In all, nearly 2,000 soldiers were reburied in the

cemetery, yet only 673 were ever identified. In two mass graves alone,

the crews placed the remains of 889 men.

|

FOR YEARS THE COLD HARBOR NATIONAL CEMETERY WAS THE FOCAL POINT FOR MANY

VISITS BY RETURNING VETERANS, SUCH AS THESE MEN WHO RETURNED IN MAY

1887. (NPS)

|

For years the Cold Harbor National Cemetery was the only area set

aside as a place of remembrance for the 1864 battle. The veterans who

returned to walk the fields and woods where they once fought naturally

made a stop at the cemetery a part of their visit. One returning veteran

recounted that as late as 1908 the evidence of war was still quite

visible as the local farmers were still finding "bodies, muskets, swords

and other implements of war." Returning veterans also chose the cemetery

as the place in which to erect their memorials. In 1909, the states of

Pennsylvania and New York dedicated two elaborate monuments to the

memory of their sons who lost their lives during the two-week

engagement. New York paid particular tribute to the 8th New York Heavy

Artillery whose 505 men killed, wounded, or missing ranks as the highest

loss of any single regiment during the battle.

The national cemeteries were established to care for the soldiers who

died in the service of the United States. The removal of Confederate

remains from the battlefields was dependent upon private organizations,

such as the Hollywood Memorial Association, which in the immediate

postwar years took pains to remove the Southern soldiers to a more

permanent resting place. The removal of the dead could not be as exact

as hoped; many of the grave sites had become overgrown and were

therefore unrecognizable. In 1915, a visitor to the Cold Harbor

battlefield wrote that while he and a companion traversed the fields on

horseback, the "sinking of their feet and breaking of bones beneath

them revealed the horrible truth that we were marching over a long

sepulchre of dead soldiers." As late as 1999, unmarked and overlooked

Civil War graves were still being discovered in the Cold Harbor

area.

|

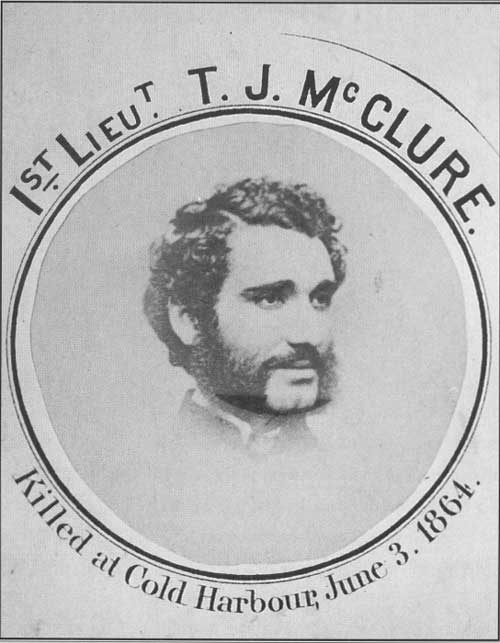

ON JUNE 3, LIEUTENANT THOMAS J. MCCLURE OF THE 7TH NEW YORK HEAVY

ARTILLERY WAS KILLED WHEN A SHELL FRAGMENT TORE OFF HIS RIGHT ARM AND

PLUNGED THROUGH HIS CHEST. FOUR MEN WERE DETAILED TO BURY HIM BEHIND THE

LINES, ERECTING A SMALL HEADBOARD ON WHICH THEY INSCRIBED: "PEACE TO HIS

ASHES; WE HAVE LOST A BRAVE, FAITHFUL, GOOD OFFICER, BELOVED BY ALL HIS

COMPANY. HIS LOSS CAN NEVER BE REPLACED. SACRED BE THE SPOT THAT HOLDS

HIS REMAINS." TODAY LIEUTENANT MCCLURE RESTS IN SECTION A, GRAVE 375, OF

THE COLD HARBOR NATIONAL CEMETERY. (NEW YORK STATE DIVISION OF MILITARY

AND NAVAL AFFAIRS)

|

Today the Cold Harbor National Cemetery contains the graves of

veterans from six different wars, the last interment having taken place

in 1970. There are only a handful of officers buried in the cemetery,

the highest ranking being a major, yet there is one Medal of Honor

recipient lying within the cemetery walls. Sergeant Major Augustus

Barry, of the 16th United States Infantry, fought in Tennessee and

Georgia during the Civil War and was awarded the medal for "Gallantry in

various actions during the rebellion." Afterward, he became the

superintendent of the cemetery, dying at this post in 1871. In 1973, the

United States Army transferred the national cemeteries in the Richmond

area to the Department of Veterans Affairs, under whose current

guardianship the graves and cemetery at Cold Harbor are well maintained

and taken care of.

|

Warren received a critical assignment. Once over the Chickahominy he

was to turn west and deploy near the crossroads hamlet of Riddell's

Shop, as though intending to attack Richmond north of the James. From

his position near Riddell's Shop, Warren was to screen from Lee the

army's move toward the James.

|

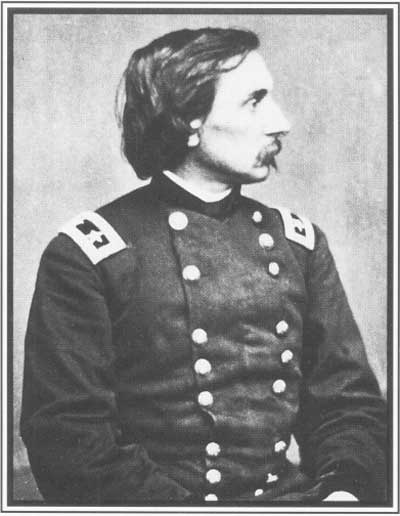

ALTHOUGH NO FURTHER ASSAULTS WERE ORDERED FOLLOWING GRANT'S REPULSE ON

JUNE 3, CASUALTIES WERE NOT UNCOMMON AS SHARPSHOOTERS WERE ACTIVE ALONG

THE LINES AND RANDOM ARTILLERY FIRE COULD OFTEN FALL WITH DEVASTATING

RESULTS. (BL)

|

|

AS COMMANDER OF THE UNION FIFTH CORPS, MAJOR GENERAL GOUVERNEUR K.

WARREN'S LACKLUSTER PERFORMANCE DURING THE CAMPAIGN INSPIRED LITTLE

CONFIDENCE IN GRANT AND MEADE (NA)

|

After dark on June 12, Grant's massive force slipped from its

earthworks. Bands played loudly to mask the withdrawal. Unlike the

Potomac Army's earlier marches, the movement proceeded like a

well-oiled machine. Meade's chief of staff Humphreys marveled at the

absence of "interruptions or delays." At 1:00 A.M. on the thirteenth,

Warren crossed the Chickahominy on a pontoon bridge and turned west as

planned. Clearing the way for Warren, Colonel George H. Chapman's

cavalry brigade encountered Confederate cavalry in force and drove them

from Riddell's Shop. Crawford's Fifth Corps division pulled up in

support of Chapman and deployed to block the routes to Riddell's Shop

and across the nearby bridge over White Oak Swamp. Screened by Warren's

infantry, the rest of Grant's force continued unmolested toward the

James.

|

|