|

MAY 25-27: GRANT ABANDONS THE NORTH ANNA RIVER AND SIDESTEPS TO THE

PAMUNKEY

By morning on May 25, Lee's opportunity had passed. Grant stood

behind strong earthworks, and seven pontoon bridges spanned the North

Anna like sutures closing a wound. Warren probed Hill's leg of the

inverted V and found it too strong to attack. Wright attempted to cross

Little River and slip behind the rebel formation, only to discover

Confederate cavalrymen controlling the fords. Hancock, on the eastern

side of Lee's V, faced two Confederate corps and decided to leave well

enough alone. The Federals contented themselves with tearing up five

miles of the Virginia Central Railroad. Sharpshooters exchanged fire,

but neither side dared assault.

Grant pondered his next move. The lessons of Spotsylvania Court House

remained fresh. "To make a direct attack from either wing would cause a

slaughter of our men that even success would not justify," he advised

Washington the next day. And flanking Lee was not promising. An

impenetrable swamp protected Lee's right, and turning the Confederate

left would require the Federals to traverse three sizable

streams—the Little River, New River, and South Anna—all the

while separated from their supply line. The solution, Grant concluded,

was to withdraw, shift east, then slice south across the Pamunkey. From

there, he could draw provisions from the Chesapeake—White House

Landing on the Pamunkey would supplant Port Royal on the Rappahannock as

the supply depot—and he would have but one river to cross. Once

again, Grant would maneuver around Lee's right flank, as he had done

after the battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House.

Lee's failure to attack at the North Anna persuaded Grant that the

Army of Northern Virginia's days were numbered. "Lee's army is really

whipped," he crowed to Washington.

|

Lee's failure to attack at the North Anna persuaded Grant that the

Army of Northern Virginia's days were numbered. "Lee's army is really

whipped," he crowed to Washington. "A battle with them outside of

intrenchments cannot be had." He added, "I may be mistaken, but I feel

that our success over Lee's army is already ensured." A few days hence,

Grant's overconfidence was to cost the Federals dearly. Lee might have

lost his capacity to launch offensive operations, but he could still

administer painful stings while acting defensively.

After dark on May 26, muffled treads from Warren's and Wright's men

sounded hollow tattoos on pontoon bridges. Boughs silenced the steps of

Hancock's corps traversing Chesterfield Bridge. "Night intensely dark

and roads very muddy," noted an aide of the crossing. By morning, the

Union army stood united on the river's northern shore, thankful for

deliverance. "How we longed to get away from the North Anna" a Federal

reminisced, "where we had not the slightest chance of success."

|

THE CHESTERFIELD BRIDGE AS PHOTOGRAPHED ON MAY 25, 1864. (LC)

|

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

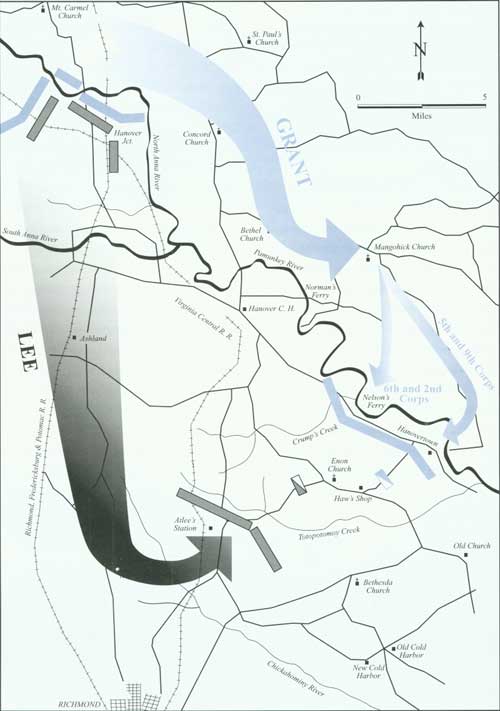

NORTH ANNA TO THE PAMUNKEY: MAY 26-28

Realizing the weakness of his position, on May 26 Grant pulls

back to the north bank of the North Anna and begins to move east and

south toward the Pamunkey River. Lee falls back along the vital railroads

and takes up a position along Totopotomoy Creek, The next day,

Sheridan's cavalry fords the Pamunkey at Nelson's Ferry and Hanovertown,

thus opening the way for Grant's columns to cross early on the

twenty-eighth. Cavalry from both sides scouts the country between the

armies in search of evidence as to the other's movements.

|

On May 27, Grant started east on a long march around Lee's right

flank. Burnside and Hancock lingered behind to guard the North Anna

fords while Warren and Wright headed for the Pamunkey River crossings

above Hanovertown, thirty-four miles distant. Major General Philip H.

Sheridan's cavalry, recently returned from its foray to Richmond, led

the way, patrolling side roads to screen the army's advance. Grant

pitched his tent for the night at Mangohick Church, three miles above

the Pamunkey. He suffered from a migraine headache so severe that he

took chloroform to relieve it. His army—"tired and hot," according

to an aide—sprawled across the countryside for miles around.

|

BEFORE LEAVING THE NORTH ANNA, UNION TROOPS FINISHED DESTROYING THE

RICHMOND, FREDERICKSBURG, AND POTOMAC RAILROAD BRIDGE. (LC)

|

Lee reacted swiftly and sent a fought-out brigade of three North

Carolina cavalry regiments along the Pamunkey's southern bank to scout

Grant's movement and harass the Federals where possible. His infantry

meanwhile drew south along the railways, putting the Army of Northern

Virginia southwest of Grant, where it could shift to counter the

Federals' likely moves. If Grant made west for the rail lines, Lee would

be there to meet him. If he began another crablike movement south, then

dashed for Richmond, Lee could follow along a smaller interior arc and

parry his thrust. Most important, Lee's move put another river between

himself and the enemy. Meandering diagonally betwixt the antagonists

ran Totopotomoy Creek, an obscure, high-banked Virginia waterway

destined to lend its name to history.

Late on May 27, Torbert's Union cavalry crossed the Pamunkey near

Hanovertown and engaged the North Carolina troopers, who offered stout

resistance as they retired before Torbert's superior numbers. Word of

the engagement confirmed for Lee his hunch that Grant intended to cross

the Pamunkey near Hanovertown.

Lee spent the night puzzling through his options. He was a mere nine

miles from Richmond. Backed against the Confederate capital, his

mobility was severely restricted. A single misstep could spell disaster.

Early on the morning of May 28, he described his thinking in a letter to

the Confederacy's president, Jefferson Davis. Grant clearly meant to

advance on Richmond, but it was too soon to determine his line of

march. "The want of information leads me to doubt whether the enemy is

pursuing the route [through Mechanicsville] or whether, now that he

finds the road open by Ashland, he may not prefer to take it," Lee

wrote. "Should he proceed on the road to Mechanicsville, the army will

be placed on the Totopotomoy. Should he on the other hand take the

Telegraph Road, I shall try to intercept him as near Ashland as I can."

To perfect his dispositions, Lee put Ewell's corps on his far right,

touching Totopotomoy Creek at Pole Green Church and closing Shady Grove

Road to Grant; Anderson formed west of Ewell, behind Hundley's Corner;

Breckinridge deployed across the Richmond-Hanovertown Road near

Totopotomoy Creek; and Hill secured the Confederate left, east of the

Virginia Central Railroad near Atlee's Station. Whichever approach to

Richmond Grant chose, Lee was confident that he could shift to meet

him.

|

|